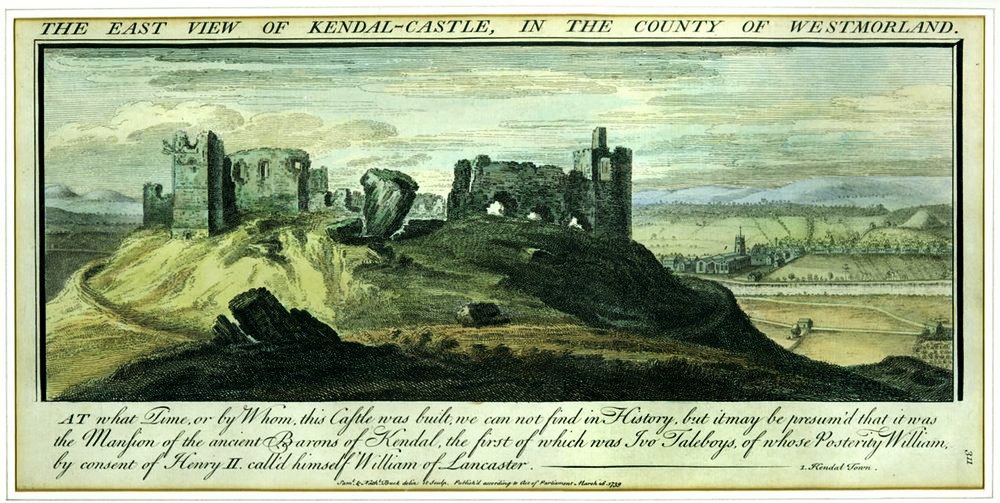

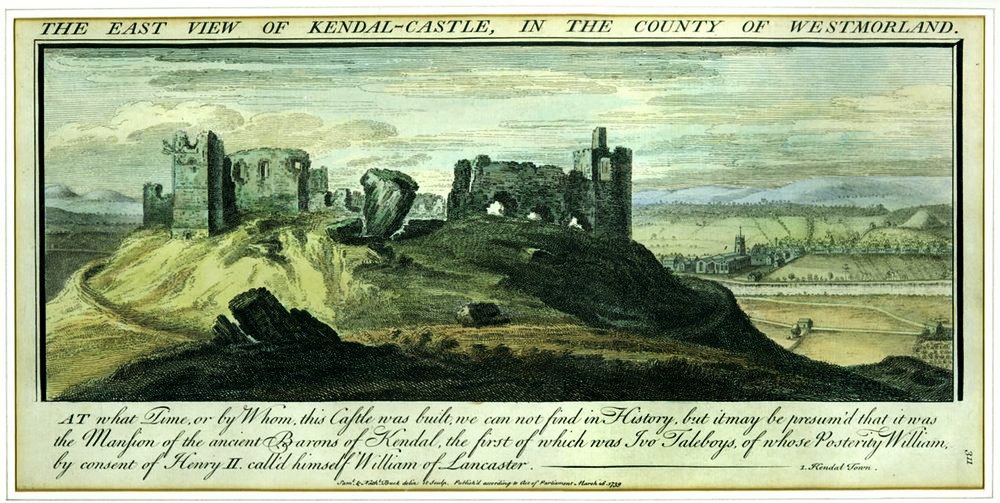

Kendal Castle

The town of Kirkby in Kendale, as Kendal was known in the Middle

Ages, was probably founded in the post Roman period, although a gold

coin of Marcus Aurelius (161-180AD) was said to have been found within

the castle walls before 1810. The town and later castle lay

in a district called Kentdale which was named after the River Kent

which ran from north to south through a valley. Such valleys are

known in the North as a dales. Other districts in the area were

called Amounderness [which stretched around Morecambe Bay from Preston

to Kendal to Millom], Lonsdale, Cartmel,

Furness and Copeland. These pretty much surrounded the wide

estuary of Morecambe Bay. By the first quarter of the thirteenth

century Kentdale was considered the southern half of the new county of Westmorland, the lordship of Appleby being the northern portion.

Kendal may have begun its military history with the reconquest of Cumberland

from the Vikings in the tenth century. Certainly the partially

built over Hall Garth, lying a little over a mile northnorthwest of

Kendal castle, is thought to be a Saxon burgh. However, only

excavation could help with deciphering the history and fate of this

site. At the time of the Domesday Survey in 1086 this district

seems to have lain to the east of ‘Hougun', an area stretching

from Furness along the coast to the later barony of Kendal. All

of this area was royal land in 1086 and appeared to have been waste

both before and after 1066. Under King Edward (1042-66) the area

around Kendal was held by Gilemichael. He held 13 manors in

Amounderness, stretching from Ellel, just south of Lancaster, to Strickland Roger (just beyond Kendal) in the north. At the time Kendal was known as Churchby (Cherchebi)

which eventually mutated into Kirkby Kendal. The block of land

that formed the basis of the later Kendal barony was listed as

Strickland Roger (Steredland), Mint House (Mimet), Kirkby Kendal (Cherchebi), Helsington (Helsingetune, near Sizergh), Stainton (Steinain), Bothelford (Bodelforde, now Natland), Old Hutton (Hotun), Burton in Kentdale (Borain), Dalton in Kentdale (Dalain) and Patton (Patun).

In this district around Kendal there were 20 carucates of geldable

land. These territories basically lie along the River Kent, with

the 2 outliers of Burton and Dalton in Kentdale some 6 miles south of

the main grouping around Kendal. It should be noted here that

these 2 vills lay closer to Kirkby Lonsdale

than to Kirkby Kendal. These 2 Kirkbys were quite separate

although the barony of Kendal acquired an interest of a quarter of the

manor by the reign of Henry III

(1216-72). Probably this dated back to the time of Ivo Taillebois

(d.1094/97) who seems to have held the entire manor. Kirkby Lonsdale

belonged to Torfin's manor of Austwick in 1066 and was in the king's

hands in 1086. However, since both places were often referred to

as merely Kirkby, Kirkby Kendal and Kirkby Lonsdale

are sometimes confused. In her work, The Mottes of North

Lancashire, Lonsdale and South Cumbria, Mary C Higham notes that the

mottes along the Lune valley probably marked the extent of Norman

military control at Domesday. All of these places mentioned

around Kendal are some 15 miles above this line. The lack of

Norman control is emphasised by the fact that only placenames are

returned in the great survey and no details of the settlements are

given.

In 1092 King William Rufus (1087-1100) completed the annexation of all of present day Cumberland

when he fortified Carlisle. It may have been at this time that

Ivo Taillebois (d.1094/7) founded a castle at Kendal, possibly at

Castle Howe, although a castle may have been founded earlier as this

seems to mark the northern extent of the English lands recorded in

Domesday. Brough castle, some 25 miles

northeast of Kendal, seems originally to have formed part of the Norman

(and earlier Saxon) parish of Kirkby Stephen, the church of which was

granted by Ivo Taillebois (d.1094/97) to St Mary's of York under Abbot

Stephen (1180/9-1112). This grant consisted of:

half the lordship of Kirkby Stephen (Cherkaby Stephan) with the church and tithes; 2 bovates and tithes in Whittington (Wytuna - just south of Kirkby Lonsdale); the churches of Kendal (Kircabi in Kendale/Cherkaby Kendale), Heversham (Eversham) and Kirkby Lonsdale (Cherkeby Lonnesdala) together with the lands which pertained to them, namely the vill of Hutton, the church of Beetham (Bethome), the land called Haverbrack (Halfrebek,

a hamlet of a mile northwest of Beetham) and the church of Burton [in

Kentdale] with a carucaste of land with the common and Clapham (Clepeam, Yorkshire) church with a carucate. This is witnessed by Lucy (Bolingbroke, d.1138) my wife, Ribald my son in law (d.1121+, Middleham), Ralph Taillebois, Robert Clerk, Girard St Alban and many others.

The confirmation of this by Henry II is slightly different and stated that this consisted of;

3 carucates in Claxton (Claxtuna), the church of Kirkby Stephen, and 3½ carucates. In Whittington (Wintona) 2 bovates and his tithes; the church of Kirkby in Kendal with its appurtenant lands and the vill called Huttoncroft (Hotonrofft);

the church of Beetham and the land called Haverbrack; the church of

Burton [in Kentdale] with its appurtenances and 1 carucate; and the

church of Clapham with a carucate.

As Ivo controlled Kendal church it is all but certain he held the rest

of the parish running along the River Kent. After Ivo's death his

widow, Lucy Bolingbroke (d.1138), was married by Roger Fitz Gerold

(d.1098) and then Ranulf Meschin (d.1129). It is presumed that

Kendal passed with the lady to these husbands in turn.

Subsequently around 1120/22, Ranulf returned Appleby, Carlisle and Kendal to King Henry I (1100-35) when he received the earldom of Chester in recompense.

At this point William Roumare (d.1159/61), the son of Lucy Bolingbroke

(d.1138) and Roger Fitz Gerold (d.1098), claimed all of his father's

inheritance. Presumably this amounted to Carlisle, Appleby

and Kendal as this was described as the land ‘which Ranulf

Bayeux, his father in law, had exchanged with the king for the earldom

of Chester'. However, the

king is said to have contemptuously refused his request, despite

William having upheld his cause in Normandy during the war of

1119. This caused William to cross to Normandy and foment revolt

against King Henry (1100-35). For 2 years he is said to have:

vented his wrath by

plundering and firing the country and taking many captives, nor did he

relinquish his attacks until the king made him satisfaction, and

restored to him the greater part of the domains which he had claimed.

William fought for the rebels at Bremule in 1123 and managed to flee

the battlefield when all was lost. With his making peace with King Henry,

William was admitted among the king's courtiers and intimate friends,

the monarch even procuring for him a well-born wife, Hawise Redvers the

daughter of Richard (d.1107). However, the lands granted to him

did not include Appleby, Carlisle or Kendal.

Probably within a year or 2 of Kendal's surrender to the Crown by Ranulf Bayeux (d.1129) in 1120/22, King Henry

(d.1135) granted Kendal and the surrounding district to Nigel Aubigny

(d.1129). These additional lands included Sedbergh, Thornton in

Lonsdale, Burton in Lonsdale, Bentham, Clapham, Austwick and Horton in

Ribbesdale, besides vills in Craven around Skipton.

This may have been done to counterbalance the lands of Stephen of Blois

(d.1154) who around 1114 had been granted the honour of Lancaster

which included Furness, Cartmel, Amounderness, parts of Lonsdale and

the land to the south known as Between Ribble and Mersey. Kendal

and Kentdale are not mentioned during this period and do not apparently

appear in the 1131 pipe roll. Their ownership is therefore

debatable, although it seems from a charter of Richard I (1189-99) that Aubigny was granted seisin.

Nigel Aubigny (d.1129) was the second husband of Matilda Laigle

(d.1155+), who had been divorced from Earl Robert Mowbray of

Northumbria, the lord of the castles of Bamburgh, Newcastle and Tynemouth. As such he would have held the Northumbrian claim to Kendal within the wider administrative area of Cumberland.

Nigel divorced Matilda, who had only born him a daughter, a little

before 1118 and then married Gundreda Gournay (d.1155+) who bore him a

son, Roger. This Roger took his father's first wife's first

husband's name and called himself Roger Mowbray (d.1188). This

would appear to have been in deference to all the Mowbray estates he

claimed. Roger led an active career being present at the battles

of the Standard (1138), Lincoln (1141) and Alnwick (1174). He

went on the second Crusade in 1148 and finally fought against Henry II

in 1173-74, before dying, back in the king's fealty, in 1188.

During this active career it seems unlikely that he was an active lord

of Kendal, although he appears to have held the overlordship all his

life. He was also lord of the castles of Burton in Lonsdale, Kirkby Malzeard and Thirsk in Yorkshire as well as Brinklow in Warwickshire.

During the early part of Mowbray's long and eventful life most of the

North of England fell under the control of King David of Scotland

(1124-53). The affect of this is discussed under various castles

on this site as well as in general under Cumberland and Westmorland. In brief this control included the overrunning of the land from the current Scottish border as far south as Newcastle and the line along the River Ribble from Skipton, via Clitheroe to Preston between the years 1136 and 1157. In the latter year King Henry II

(1154-89) persuaded King Malcolm IV of Scotland (1153-1165) to return

the conquests of his grandfather, King David (1125-53) to him.

Quite what happened in Westmorland

during this period of Scottish supremacy is open to question as the

district rarely appears in contemporary documentation, but Mowbray

seems to have regained or retained rights in the area, although Hugh Morville

(d.1201) certainly acquired some rights in this district at some point

before 1173 judging from the later enigmatic mentions of some of his

actions in the pipe rolls.

At some point early in his career, possibly when the Northwest was

threatened by or even under King David's rule, Mowbray made a grant

that ran:

Roger Mowbray to all his French and English men, greetings. Know that I have given and granted to William Fitz Gilbert of Lancaster

in fee and inheritance, that is, all my land of Lonsdale (Lonsdall),

and of Kendal, and Horton in Ribblesdale, with all their appurtenances;

to hold well and in peace, quietly and freely and honourably, in the

forest, in the plain, in the waters, in the mills, and in all things,

with soca and sacca, and tolnet, and infangenthiefe, with all customs,

free and right; by the service of 4 knights.

Quite clearly from this, Roger was holding the Mowbray lands in Lancashire and Westmorland

at the time. Much later around 1290, it was recorded that Rose

Clare (d.1316+), the wife of Roger Mowbray (d.1297), held presumably

her dower portion in Ewcross Hundred. This consisted of 5

carucates in Thornton in Lonsdale of which Enguerrand Guines (d.1324),

a lord of a part of Kendal barony also held lands. Rose also held

in Clapham, Dent, Sedbergh, Ingleton, Bentham and Austwick. Quite

clearly Mowbray control of this district had been maintained, even if

Kendal had been lost.

The idea that Gilbert Lancaster (d.bef.1134), the father of the above William Fitz Gilbert of Lancaster

(d.1170) held Kendal as heir to Ketel Fitz Eldred (d.1115+) is merely a

flawed attempt to explain the above grant. This misrepresentation

was concocted at some point between 1263 and 1283. Amongst the

records of St Mary, York, was a pedigree of Ivo Taillebois

(d.1094/7). This attempt to sort out the past was made during the

lifetime of Christiana Lindsay (1267-1320+), an heiress to parts of

Kendal barony, probably before her marriage to Enguerrand Guines

(d.1324) which occurred before 28 May 1283. As such the author's

knowledge of what occurred in the early twelfth century was probably

based upon the surviving charters found in St Mary's chartulary and

this accounts for the understandable error.

William Fitz Gilbert (d.1170) may well have acquired the surname Lancaster before 1149 when he witnessed a charter for Earl Ranulf of Chester (d.1153/4). This was made when the 2 were together in Lancaster. As such it is quite possible that William was already constable of Lancaster castle

for Earl Ranulf. Despite this suggestion, it is difficult to say

when William became lord of Kendal. This had possibly happened

before 1149, when he was already a man of substance, but possibly as

early as the summer of 1138 by which time King Stephen (1135-54) was losing control of the North of England. Possibly early in this period, King Stephen or his son, granted Warton in Kentdale [Morhull castle]

to William along with Garstang in Lancashire for the service of one

knight. Certainly, William Fitz Gilbert (d.1170) appeared in a

charter dated to between 7 November 1153 and 1155 confirming gifts of

his lord, Count William of Mortain (d.1159), the son of King Stephen

(d.1154), in Furness. It has been suggested from this that the

grant to William Lancaster (d.1170) of 36½ carucates of land in

Ulverston, Warton and Garstang in Lancashire for the service of 1 knight might have been granted by either King Stephen or his son, Count William of Boulogne (d.1159), who was lord of Lancaster as well as the castles of Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Eye, Lewes, Norwich and Pevensey.

The heirs of William Lancaster (d.1170), Gilbert Fitz Remfry (d.1220) and his wife, Hawise Lancaster, were holding Warton of the Crown later in the twelfth century as part of the honour of Lancaster.

It has further been suggest that such a grant may first have been made

by Count William of Boulogne (d.1159), the son of King Stephen,

to William Lancaster in the period 1153 to 1159. It is thought

that William Lancaster's father, Gilbert (d.bef.1134), or a

predecessor, had been granted lands in Cumberland,

namely Muncaster, Hensingham, Preston [north of St Bees], Lamplugh and

Workington as well as Barton [south of Ulswater] and Morland, by

William Meschin (d.1130/34) or even Henry I

(1100-35). All of these lands lie well north and west of Kendal

and were presumably lost during the time of Scottish rule

(1138-57). Gilbert himself would appear to have been dead by 1134

at the very latest by which time William le Meschin (d.1130/34), the

husband of Cecily Romiley (d.1151/55) of Skipton, had confirmed the gift of William Fitz Gilbert Lancaster of Swartha Brow (Swartahof, near Whitehaven) to St Bee's priory.

Much later, the Warton part of the Lancaster

inheritance was held by Gilbert Remfry (d.1220) and Hawise Lancaster,

his wife. The idea that William Fitz Gilbert:

obtained the king's licence

to be called William Lancaster and to be summoned before the king in

parliament as Baron William Lancaster of Kendal...

is obviously a later fiction, not invented until after May 1283 when

Christiana Lindsay (d.1320+) married Enguerrand Guines (d.1321+).

Unfortunately the current idea of lords being made ‘barons' by

summons etc is a modern conceit, which really shouldn't even need

discussing. There would appear to have been a castle at Kendal

from the Norman era at least, so theoretically a lord of Kendal might

have been regarded as a baron at any time since the Norman

Conquest. Baronage was not a title given out by kings, by summons

or any other means. It was a word, probably derived from the Old

Germanic, baro, which meant a

freeman. In the Middle Ages it was used simply to describe

powerful knights who were lords over other knights and usually owed

allegiance direct to the king. As such attempts to describe such

people as third, fifteenth or any other such numbered ‘baron' of

Kendal or anything else should be consigned to the anachronistic

dustbin of historical fantasy.

The major religious house in southern Cumberland and Westmorland was undoubtedly Furness abbey, founded by King Stephen in the 1120s while he was still a baron of King Henry I

(1100-35). The barons of Kendal often found themselves in

conflict with these monks over the bounds of the mountains between

Kendal and Furness. These lands stretched between Lake Windermere

and Ulverston. One consequence of this dispute is that Furness

probably obtained the most royal protections of any church in England,

receiving confirmation of their lands from Henry I, Stephen, Richard I,

John, Henry III, Edward I, Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V

and Henry VI. Their lands were also confirmed by Pope Eugenius

(1145-53) and then by Pope Innocent III (1198-1216), twice!

With control of the North established by King Henry II

in 1157, he confirmed an important charter before 1163, in which he

described the boundary between Furness abbey and Kendal lordship as it

was then held by William Fitz Gilbert (d.1170). These boundaries

were written down in Henry's court at Woodstock by Chaplain Stephen in

the following terms:

that my charter confirmed the

agreement which was brought before me between the monks of Furness and

William Fitz Gilbert, concerning the mountains of Furness in this

form. Furness Fells are divided from Kendal according to these

terms, as was sworn at my writ by a minimum of 30 men. As the

water descends from Wrynose Haws (Wremesale) into Little Langdale (Langedene-little), and thence into Elterwater (Helterwatra), and thence through the [River] Brathay (Braiza) into Windermere (Windendermer), and thence into the [River] Leven (Levenam),

and thence to the sea. However, this land was divided by the

abbot of Furness by these divisions as written; from Elterwater (Helterwatra) to Tilburthwaite (Tillesburc), and thence to Coniston (Coningeston), and thence to the head of Coniston Water (Turstiniwatra), and along the bank of the same water to the [River] Crake (Cree) and thence to the [River] Leven (Levene).

William, however, himself elected to have that part which adjoins these

boundaries on the western side, to be held of Furness abbey, wholly and

fully in the forest and plain, in the waters and fisheries, and in all

things, rendering thence to the abbey of Furness 20s and the son of the

same William [William Lancaster, d.1184] will do homage for it to the

abbot. Wherefore I will and firmly command that this agreement be

held firm and unshaken, and that the same abbey shall have and hold its

aforesaid part well and in peace and whole, in forest and plain, in

waters and fisheries, and in all places and things, but that part which

adjoins the same boundaries on the eastern side is held by the same

abbey, except that William will have game and hawks on that side.

This was witnessed by bishops Robert of Lincoln (1152-66) and Hugh of

Durham (1153-95), Earl Roger of Leicester (d.1168), Richard Lucy

(d.1179), William Vescy (d.1183, father died 1157), Geoffrey Valognes

(d.1208), William Egremont (d.1163), Albert Gresley (d.1181), John

Constable (d.1190, Clavering), Richard Pincerna, Henry Fitz Swein

(d.1172), Gospatric Fitz Orm (d.1185) and Richard Fitz Ivo.

This agreement was also copied into the Furness Coucher as an important

statement of the abbey's lands and rights. After this the monks

made a precis of what this meant to Furness abbey. This again is

obviously a late concoction and reads:

This was the first William

who caused himself to be called, by the lord king's license, Baron

William Lancaster of Kendal, who was formerly called Taillebois.

Of course this is total tosh. The title ascribed to William did

not exist as such in the twelfth century and he was almost certainly

never called Taillebois. This supposition probably dates more to

the fourteenth or even the fifteenth century. The idea that

William Fitz Gilbert was called Taillebois is quite simply a

misrepresentation of the early holding of the district by Ivo

Taillebois (d.1094/97) and is probably based simply upon the fact that

the writer of this note had seen the charter whereby Ivo made grants in

the district. This later text continued that William:

who married Countess Gundreda

of Warwick, who in fact begat William the second from the aforesaid

Gundred. This William II married Helewisa Stuteville, by whom he

had only Helewisa. This Helewisa was married to Gilbert Fitz

Roger Fitz Remfry (Reynfredi),

in whose time the following fine was made concerning the exchange of

the vill of Ulverston with part of the mountains [Furness Fell].

There then followed in the Coucher the fine made by Gilbert before King Richard I (1189-99) in 1196 which will be examined a little below.

As can be seen, not a lot is known of William Fitz Gilbert's career in

Kendal, but he died before Michaelmas 1170 when Richard Morville

(d.1191/96) proffered 200m (£133 6s 8d) for having the lands he

claimed in right of his marriage to William Lancaster's daughter.

Richard paid 80m (£53 6s 8d) of this in 1172 and the remaining

120m (£80) in 1175, while the lady herself died on 1 January

1191. This lady, Avice Lancaster (d.1191), was possibly

illegitimate as the grant would seem to have partially disinherited

William Lancaster (d.1184), the heir to Kendal. This would have

explained the large Morville fine of 200m (£133 6s 8d).

Before 1156, William Lancaster (d.1170) had married Gundreda Warenne

(d.1175/84), the widow of Earl Roger Beaumont of Warwick (d.1153) and

aunt of Count William of Mortain (d.1159). By this marriage,

Countess Gundreda became lady of Kendal. She had had at least 6

children with Earl Roger of Warwick (d.1153) and in her new marriage

was probably the mother of William Lancaster (d.1184), but not

Avice. Avice had married William Peverel who had died before

1152, which suggested she herself was born before 1135. Obviously

this was nearly 20 years before William Lancaster and Countess Gundreda

married around 1153. She died in 1191, therefore aged over

56. William Lancaster (d.1184), is first probably mentioned in

1176 which would fit with a post 1153 marriage date. It has been

argued that Gundreda was too old to bear children after 1153.

However, her birth could have been as late as 1120 and was certainly no

earlier than 1118 when her mother's first husband, Earl Robert Beaumont

of Meulan and Leicester, died. She was the daughter of Countess

Isabel Elizabeth le Magne of Meulan and her second husband, Earl

William Warenne (d.1138). The date of Gundreda's first marriage

is not known, but Earl William of Warwick (d.1184), her eldest known

child, was probably not born until after 1138 as he appears to have

been underage in 1153 at his father's death. This makes the claim

that she was too old to bear children in the 1150s nonsense. As

lady of Kendal, Gundreda appeared in charters for her husband and bore

him at least 2 sons, Jordan, who was dead by 1160 and William, their

eventual heir as can be seen in this charter.

To all the faithful of God's

holy church, from William Lancaster greetings. Let it be known to

everyone that I, by the advice and consent of William, my son and heir,

and of Gundreda my wife, and for the health of my Lord King Henry of England and Queen Eleanor

and their children, and for the health of our souls, and the souls of

Gilbert my father, and Godith my mother, and Jordan my son, and

Margaret daughter of the Countess, and for the souls of my parents and

all ancestors, have given and granted, and by this present charter

confirmed in pure and perpetual alms to God and the church of St Mary

de Pre of Leicester, and to the regular canons serving God there, and

to their men of Cockerham, full and free common right throughout my fee

in Lonsdale and Amounderness, in wood and plain, in waters and

pastures, in feeding grounds and in all other necessities, and that

they and their men shall be quit of pannage in the aforesaid

places. Wherefore I will and firmly charge that the aforesaid

canons and their men of Cockerham shall have all their easements and

their cattle in the aforesaid places free and quit of all service and

exaction towards me and my heirs, as they have in their own demesne

underwood, which extends to the bounds between Cockerham and Thurnham,

to wit, to the water which is called Flackes-fleth which runs down into

the Crokispul, and so into the Lune (Loin);

and I prohibit any of my heirs or servants from causing any injury,

loss or hindrance to the said canons or their men, but that they shall

have and hold the said common right freely and quietly for evermore, as

this my charter bears witness, with all the liberties and free customs

which I myself had in the said manor of Cockerham, whilst I held it in

my own demesne. This is witnessed by William my son and heir,

Gundreda daughter of the Countess, Robert the Chaplain, William the

Chaplain of Walton, Ralph Fitz Nicholas, Robert le Heriz, Robert

Mundegune, William Fitz Daniel [le Fleming of Thurnham], Robert Mustel,

Robert the Chamberlain, William Kair, Thomas Fitz William, Matthew Fitz

William Malesturmi, Albert Cardula, Matthew Leuns, and many others.

The implication from this is that Countess Gundreda was the moving

force in William Fitz Gilbert making his grant of Cockerham to

Leicester abbey which was the foundation of Gundreda's half brother,

Earl Robert of Leicester (d.1168). As such this shows William as

a part of the fraternity that would oppose King Henry II

(1154-89) in the great rebellion of 1173-74. Incidently the

Gundreda, daughter of the countess, in the charter is the lady who

married Earl Hugh Bigod (d.1176) before 1160 and founded Bungay nunnery.

The above charter shows all that is known of the real parentage of

William Fitz Gilbert Lancaster. He was the son of an otherwise

unknown man called Gilbert, who's wife, Godith, is guessed to have been

the daughter of Eldred and Edgitha. These 2 were certainly the

parents of Chetell/Ketell Fitz Eldred (d.1115+), who in turn was father

of Orm Fitz Ketel (d.1094/1102), the father of the more famous

Gospatric Fitz Orm (d.1185) of Appleby castle

infamy. William Fitz Gilbert (d.1170) seems to have taken on the

surname of Lancaster, possibly as he was constable of that fortress for

Count William of Mortain (d.1159) or King Stephen

(1135-54). He may possibly even have been constable for Earl

Ranulf of Chester before 1149 as has been noticed above.

Certainly the surname was in use from as early as 1141, before which

William Lancaster was lord of Muncaster [Mulcaster, lying half way between Millom and Egremont castles] in the fee of King Stephen

(1135-54). That said, he was named simply as William Fitz Gilbert

when he confirmed the boundary of his lands in Furness Fells with the

monks of Furness around July 1163. This boundary in Furness Fells

which divided his lordship in Kendal barony from the abbey's lands was

again described as from where:

the water which descends from Wrynose Haws (Wreineschals) into Little Langdale (Langedenelittle), into Elterwater (Heltwater) and through the Brathay (Braiza) into Windermere and then into the Leven (Leuena) and so into the sea.

Through this division the abbot took the land:

from Elterwater (Heltewater) to Tilburthwaite (Tillesburc) and to Coniston (Conigeston) and then to the head of Coniston Lake (Turstiniwater), along the bank of that water to the Crake (Crec) and then into the Leven (Leuenam).

This boundary was later confirmed by the Young King, Henry III (1170-83), as running:

down from Wrynose Haws (Wraineshals) into Little Langdale (Langdenelitle) into Elterwater (Elterwater) then through the Braithay (Braitha) into Windermere (Wynandrem) then to the Leven (Leuena)

and from there through.... to the sea. The division between

Copeland and Furness ran along the water descending from Wrynose Haws (Wraineshals) into Trutehil thence through the Duddon (Dudena) to the sea.

It seems from pipe roll evidence that Kendal was later held directly from King Henry II

(1154-89) by the service of £14 6s 3d by noutgeld [a manorial

rent which was originally paid in kind, often cattle, but then commuted

to a cash sum]. This is suggested by the fact that William only

owed Roger Mowbray 2 new, ie post 1135 fees in 1166, rather than the 4

of the original charter by which Roger Mowbray (d.1188) granted him

Kendal with the other lands. The implication is that Kendal was

now held directly of the Crown for the missing 2 fees, although William

himself apparently did not make a 1166 charter for any lands he held in

chief, ie Kendal. It has been suggested that Kendal was held of Hugh Morville (d.1202) of his suggested barony of Westmorland

before 1174, but there is little evidence of this, although Morville

does seem to have held extensive rights within the county, judging from

comments in later pipe rolls about his interference in the running of

the county. Regardless of this, the throwaway line in Fantosme

that the Young King (d.1184) offered King William the Lion of Scotland (1165-1214):

the land which thy ancestor had;

Thou ne'er had so great an estate in land from the king,

The borderland; I know no better under heaven.

You shall have the lordship in castle and in town;

All Westmarilande without any gainsaying...

again shows that Westmorland was currently royal land and probably not held as a fief by the Morvilles. As such the county should have included both Kendal and Appleby

and from this it is apparent that the king had control of this district

and therefore the right of granting it away without any reference to

its alleged Morville owner. Further, Henry II's

interest in Kendal is indicated by his confirmation of the boundary

between Furness abbey and William Fitz Gilbert's land of Kendal.

William Lancaster was last heard of in 1170, when both he and Gospatric

Fitz Orm [William's first cousin 1x removed] pledged 5m (£3 6s

8d) each, amongst others, for the 35m (£23 6s 8d) debt that

Robert Fitz William had entered into for having the king's peace.

The debt was duly noted for the next 2 years, despite William

apparently being dead. At William's supposed death in 1170, his

heir, William Lancaster (d.1184), must have been under age as, if his

mother was Countess Gundreda Warenne as appears probable, he could have

been no older than 17. Certainly no relief fee was recorded as

having been charged to the Young William Lancaster (d.1184) in the pipe

rolls and he must have come of age before 1176, judging from his

appearance as William Fitz Gilbert and Countess Gundreda's heir before

1160 which would suggest a birth date of before 1155. It is rare

for youngsters below the age of 5 to appear in charters. The

status of Kendal barony in the 1170s is therefore something of a

mystery.

In 1173, Roger Mowbray (d.1188) rose in revolt against Henry II

(1154-89). Possibly Kendal lordship followed him in this,

although whether there was a functional castle in this southern portion

of Westmorland at the time is a moot

point. Despite this speculation, without further evidence, it

probably seems best to accept that Kendal stayed loyal to Henry II.

To strengthen this assumption is the duel fought between William

Lancaster (d.1184), assuming this is the correct identification of

William Fitz William) and his second cousin, Gospatrick Fitz Orm

(d.1185). It was this Gospatrick who had surrendered Appleby castle to King William of Scots in 1174, possibly obeying the instruction of the Young King, Henry III (1170-83) and certainly against his fealty to Henry II. However, Kendal (Kendala) appears to have been under the control of Sheriff Ranulf Glanville (d.1191) of Westmorland

when he recorded the income of 20s from the town fishery in 1177.

He also paid 1m (13s 4d) in noutgeld which was possibly also for

Kendal, but this is very low it if was - in the 1190s this was worth

nearly £15 a year. Glanville had been in charge of Westmorland

since 1174, but it was only in 1177 that he managed to enter accounts

for the last 3 years. It is uncertain from this what the status

of Kendal barony actually was at this time. Had it rebelled and

been retaken by Glanville? Certainly William Lancaster, who must

have come of age around the time of the war, was not fined for any

treachery as so many of his contemporaries were. This suggests

that he remained loyal and the sheriff was merely recording monies paid

from the lands of Kendal while the heir was underage. The idea

that the entirety of Westmorland was

passed to Theobald Valoignes (d.1209) in 1178 is almost certainly

erroneous. The argument goes that as he paid a relief on 6

knights' fees these must relate to 4 for Appleby

and 2 for Kendal. However, Theobald was the nephew of the sheriff

and later, in 1184, paid 100s relief in Yorkshire, again to Sheriff

Ranulf. If Theobald had obtained Westmorland

in 1178 by payment of this ‘relief' it is unbelievable that he

did not hold it at his death in 1209 when his son, Thomas, was charged

300m (£200) and 3 palfreys for his relief of the family lands in

Norfolk and Suffolk to be paid off at 100m (£66 13s 4d) pa.

Although there is no evidence to suggest when William Lancaster (d.1184) acquired his inheritance of Kendal barony and Morhull castle,

they were certainly in his hands some time before his death in

1184. He was then described as ‘a man of great honesty and

possessions'. That same Michaelmas of 1184, the men of William

Lancaster of Kendal were assessed and paid 10m (£6 13s 4d), their

lands apparently being in the hands of the sheriff. The lands

being in the sheriff's hands at this time was most likely due to

William having recently died. Other than this there is no royal

record of Kendal otherwise being in the sheriff's hands.

The tenure of William Fitz William (d.1184) over his estates is fraught

with difficulty. All that can be said with certainly is that he

did hold them, for he was claimed to have dispossessed the canons of

Cockerham of his father's gift within the barony. This gift later

passed to Hugh Morville (d.1202)

with William Lancaster's widow, Helewisa Stuteville (d.1228+). As

he appears to have been holding this as his wife's marriage portion it

hardly implies that he was once lord of Westmorland

as is occasionally suggested. Unusually it was as late as 1181

that William Lancaster's executor was granted 6d by the king's writ in

Surrey. Presumably this was for the will of William Fitz Gilbert

Lancaster who had apparently died in 1170. In the period 1180 to

1184, William Lancaster (d.1184) made a grant to the brethren of

Conishead of lands that included Ulverston. It seems likely from

this that he was in charge of Kendal by this time. He also in

this period granted Dunnerdale and Seathwaite in Furness, which lay

between the rivers Lickle and Duddon, to William Fitz Roger. This

area lay due south of Hardknott Roman fort and had been granted by

William Lancaster (d.1170) to Roger Fitz Orm, the father of this

William Fitz Roger. This was confirming the grant of

‘Gilbert, the father of William Lancaster, giving Roger the land

between Lickle and Duddon for a render of 4s'. This would suggest

that the Lancaster family was established north of Furness possibly

from as early as William Rufus' 1092 expedition.

At some point during his occupation of Kendal barony William Fitz William Lancaster (d.1184) also made the following grant:

to the poor men of the hospital of St Peter of York, of all the land called Docker (Docherga), that is by the brook which is between Docker (Docherga) and Grayrigg (Grarigg) and between Docker and Lambrigg Fell (Lamberig) and between Docker and Whinfell (Wynfel) and between Docker and Patton (Pattun) and as the same brook flows down in the River Mint (Mynud) and between Docker and Falbec (Flodder Beck?) to where the brook flows into the River Mint and thence up that brook to below Wards and thence to Knothill (Knotlinild) and thence across to the Black Beck (Blacbec), which comes down from Warlaghasheyhes; further beyond these bounds common pasture as far the River Lune (Lon). This was in exchange for the land of Kendal (Kirkeby) which Ketell Fitz Eldred (d.1115+) gave to them in frank almoin and for the land of Bartonhead (Barton Heved)

which William, the donor's father gave them; with a further grant that

if the animals of the hospital are found without the above bounds in

the donor's forest, they shall be ejected gently and without hurt;

while horses and pigs belonging to the hospital shall be allowed to go

throughout the donor's forest. Testibus, Lady Hawise, the donor's

wife (Hawise Stuteville, d.1228+), Gilbert Lancaster (possibly

William's illegitimate son), Patrick Fitz Bernard, Robert Mustel,

Baldrick, William Pymund, Achard and Nicholas his son, Henry Fossard,

Norman Redman and Gervase and Grimbald the knights.

Chetell or Ketell Fitz Eldred was probably the granduncle of William

Lancaster (d.1184) and if the terms of this document are correct,

apparently was lord of Kendal (Kirkeby)

as he had granted that land away. If so, he was presumably

holding the land from William Fitz Gilbert (d.1170), the Mowbrays or

possibly even the king of Scots (1138-57). Though, theoretically

it is possible that he might have been holding the land from one of their

predecessors before 1138. However, if Ketell had alienated Kendal

to St Peter's prior to the 1180s then it seems unlikely that the castle

was built before the time of William Lancaster (1170-84) when he

exchanged Kendal back, assuming of course, that the new castle was

built on the land that was exchanged with St Peter's. The

archaeological evidence of the excavation seems to confirm this

deduction with their conclusion that the earthworks were not

constructed until the early thirteenth century - archaeological dating

is a highly imprecise science. This grant therefore strengthens

the suggested military chronology of Kendal, viz that an early castle

was built - apparently Castle Howe - perhaps during the time of either William I or William Rufus,

followed by the castle's abandonment and granting to St Peter's of York

when the frontier moved further north after the successful annexation

of Carlisle. Then, after reclaiming

the land from St Peter's, William Lancaster (d.1184) may have founded

the new castle at Kendal on a virgin site on the hill, rather than

destroying a portion of the town to allow the castle to be built - the

old motte and bailey castle at Castle Howe being thought obsolete and

not worthy of refortifying. Certainly this makes a sensible

reconstruction of the available evidence. It seems most unlikely

that Castle Howe was a siege castle as no great sieges are recorded, or

indeed are likely to have occurred here, viz. Aston, Brimpsfield, Corfe or Middleham.

From William Lancster's death in 1184 until 1187, Kendal with the rest of

his estates, must have been in the hands of the king, although nothing

substantial was recorded of them during this period. Helewisa

Lancaster did not appear in the Rotuli de Dominabus

of 1185 which listed many heiresses and their lands which were in royal

hands at this time. Sadly, what we have today, only covers

England as far north as Lincolnshire. What we do know is that the

king granted William Marshal (d.1219) the land of Cartmel around

Christmas 1186. He was also granted the custody of Helewisa

Lancaster and presumably it was intended that he should marry the lady

and receive Kendal as her husband. However, William seems to have

abandoned Helewisa before July 1188 when Henry II

offered William who had ‘so often moaned to me that I had

bestowed so small a fee on you', the much greater barony of Chateauroux

in Berry, France. The History of William Marshal, probably

written for William's son before 1230, puts this delicately as William

and Helewisa remaining ‘just good friends' after he passed her

over in favour of marrying first the heiress of Chateauroux and then

the even greater heiress, Isabella Clare. Consequently it seems

to have been around Lent 1189 that the Marshal was asked to let Gilbert

Remfry (d.1220) marry Helewisa Lancaster. After this had happened

King Henry II notified his son, Count Richard of Poitiers (d.1199), the future King Richard I,

that he had granted his steward, Gilbert Fitz Roger Fitz Remfry, the

daughter of William Lancaster together with his entire inheritance as

had been witnessed, by Chancellor Geoffrey, his son [Geoffrey was

chancellor from 1181], William Marshall (d.1219) himself and Richard

Hommet.

This event gave the Remfry family a major holding in the North.

They had not just arrived in royal service, but were a long standing

curial family holding a twelfth of a knight's fee in Dunmow of the

Montchesneys as well as lands in Holme and Beckingham in Lincolnshire

and Ramsden Bellhouse in Essex. Roger Fitz Remfry (d.1196) was an

administrative official and whose brother, Walter Remfry, was

archbishop of Rouen (1184-1207). Their mother was Gonilla, an

illegitimate daughter of Henry I

(1100-35), while their grandfather was dapifer to the Percys and their

great grandfather was the renowned Abbot Remfry of Whitby (d.1086)

who's name inspired Bram Stoker's character Reinfred in his 1897 novel,

Dracula. Roger had married Alice Brito, the daughter of

Louis Brito and brother of Ralph before 1165. By her he had some

5 sons and at least 2 daughters. Roger Remfry (d.1196) became a

judge before 1169 and was responsible for much building work at Arundel castle for Henry II (1154-89) and having the ditch dug around the Tower of London for Richard I (1189-99).

Gilbert had probably been born before 1160 and, following in his

father's footsteps, was a judge before 1185. By 1180, and

possibly as early as 1177, he was with Henry II in Caen

and seems to have remained in the king's entourage thereafter,

sometimes in the company of his father, Roger Remfry (d.1196), and

witnessing his last document for Henry as his dapifer just a day or 2

before the king's death at Chinon castle

on 6 July 1189. This final grant was to Theobald Walter's

foundation of Swainby. Theobald was lord of Amounderness and was

to be related to Gilbert Remfry very distantly by marriage. Count

Richard, before he was even crowned king of England on 3 September

1189, was fully in favour of the grant of Kendal to his father's man,

for he confirmed the grant at Rouen on 20 July 1189, the same day he

was officially invested as duke of Normandy. Further, on 15 April

1190, he granted Gilbert acquittance of noutgeld in all his lands in Westmorland

and Kendal, namely £14 6s 3d each year in return for the service

of a single knight. He also granted him quittance to suit of the

county, wapentake or riding court and from having to give aid to the

sheriff or his bailiffs. For this concession Gilbert gave the

king 60m (£40). The original charter was made at Evron in

Maine. However, as this was an ‘innovation', the king

reissued the charter on 5 March 1199, just a month before his death at Chalus [Chabrol] castle. The charters confirmed:

quittance through all his land in Westmorland

and Kendal of noutgeld, that is for £14 6s 3d which Gilbert used

to render. Gilbert was also quit of all shire, wapentake, tithing

and aid for the sheriff in all his bail throughout his lands, all for

the service of one knight and the payment of 60m (£40)....

Testibus Earl William of Arundel (d.1193), William Marshall (d.1219),

Constable William Hommet (d.bef.1209), Dapifer Roger Prateli and

Stephen Thurnham (d.1214) at Evron in Maine.

That was the tenor of our

charter made under our first seal. Because that was lost

while we were captured under the power of another, during a state of

war: it [this charter] was revised. And these are the witnesses

of this renewal, bishop Herbert Poore of Salisbury (1194-1217),

Archdeacon Vivian of Derby, Robert, Johel and Baldwin chaplains,

William Marshall (d.1219), William Stagno, Seneshall Robert Thurnham

(d.1211) and Robert Tregoz (d.1214). Dated at Chateau-du-Loire by

Vice Chancellor John Brancaster on 5 March 1199.

On the same day of 15 April 1190, a second charter was granted to Gilbert ran:

We will, grant and by this

charter confirm to Gilbert Fitz Roger Fitz Remfry and his heirs to have

and to hold, wholly, freely and quietly, all the forest of Westmorland,

Kendal and Furness, just as William Lancaster Fitz Gilbert ever held it

and had it, better and more whole, freer and quieter and apportioned

the same; and that they should have that forest which we gave to the

same Gilbert and his heirs in Kendal, with £6 of land; as well,

whole, free, quiet and ever better than Nigel Aubigny had and held it,

more thoroughly, freer, and quieter. We will and grant that what

was waste in the wood of Westmorland

and Kendal in the time of the aforesaid William Lancaster Fitz Gilbert,

remains all waste, except for the purprestration made by the license

and consent of the lords of the fee of Kendal and Westmorland.

Wherefore we desire and fearfully command that no one unjustly presumes

to forfeit from Gilbert himself or his heirs mentioned above upon the

forfeiture to us of £10. Witnessed by Earl William of

Arundel (d.1193) and many others

This last charter confirms that Kendal, as well as the forest of Westmorland

and Furness, had been held by William Fitz Gilbert Lancaster (d.1170)

and before him Nigel Aubigny (d.1129). This of course, confirms

the descent of Kendal barony as set out above. It should also be

noted that neither Hugh Morville (d.1201), who was back in royal favour, nor Theobald Valoignes (d.1209), are mentioned as previous holders of Kendal.

A few days before the first grant, on 11 April 1190, Gilbert was with

his king at Mortain in Normandy. The grant was obviously

effective for at Michaelmas 1190 the sheriff of Westmorland

acquitted Gilbert the charge of £7 3s 2d for the farm of Kendal

for half a year, ie from 15 April 1190 to 29 September 1190.

Doubling this sum of quittance gives £14 6s 4d, which is only a

penny out from the noutgeld owed for Kendal. The sheriff was also

acquitted for accounting for £4 9s 1d for Kendal, which the king

had given Gilbert, for half a year as well as 50s due from the

fishery. Consequently, the sheriff was acquitted this total sum

of £28 4s 6d yearly until Easter 1195 when, for a reason which

will be discussed below, the £14 6s 3d began to be charged

against Gilbert again. Despite this, during this period, King

Richard granted Gilbert a further 16 carucates of land for the service

of 1 knight's fee. This land was in Levens and included the

fishery, together with Farleton, Beetham, Preston Richard (n'r

Endmoor), Holme, Burton in Kendal, Hincaster (Hennecastre), Preston Patrick (n'r Endmoor) and Lupton (Loppetona)

with another fishery. Like the earlier charter this one too was

confirmed as an innovation at Chalus in 1199 and was probably made

before the king left France on Crusade in August 1190. Regardless

of this reissue, effectively these places were joined permanently to

Kendal barony. A further boon was another charter by King Richard (1189-99), which is thought to date to 9 December 1189 and which granted Gilbert Fitz Roger Fitz Remfry (Renfridi) a weekly market at Kyrkebi in Kendale

for a fine of 20m (£13 6s 8d). This was witnessed by

Gilbert's uncle, Archbishop Walter of Rouen. Quite clearly King Richard

had changed and raised the status of Kendal considerably. The

event of Gilbert receiving Kendal was obviously of some note, for even

a contemporary chronicler noted:

And then was conceded and given to John his brother [by King Richard]....

and Gilbert Fitz Roger Fitz Rainfrei [was given] the daughter of

William Lancaster, dapifer to his [Richard's] father, the king [Henry II]...

The event was also mentioned in the History of William le Marechal,

which had probably been written for his son, Earl William Marshall of

Pembroke (d.1231). This told how William Marshall had been

granted the guardianship of the lady of Lancaster and her great estates and how he had been guardian to her for a long time while he held her as his dear friend (chiere-amie),

but that he never married her. The long time he held her could

have been as short as 2 years for he only returned from Crusade around

Christmas 1185. Whatever the case, he had lost control of her in

1188 when Henry II upgraded his

bride from Helewisa Lancaster to the lady of Chateauroux and give

Helewisa to Gilbert Remfry. The fact that Gilbert seems to have

rapidly married the lady shows that William Marshall could have made

this match himself if he had wanted to. Quite obviously he didn't

and his moaning to Henry II

about his wanting a greater fee would therefore seem to be part of a

premeditated plan of the Marshall not to marry the lady. The

History of William le Marechal records Gilbert having Helewisa, but

puts its own spin upon it.

And if you say in good faith

That Gilbert the son of Reinfrei

Was not held back from taking the daughter

With whom he was given Lancaster

That The Marshal had in custody

of whom he was a courteous guardian.

There is no hint here that it was the Marshall who refused the

marriage. After this introduction to the affair the Marshall's

biographer went on to have King Richard

say that he freely confirmed what his father had given to Gilbert as

well as his gifts to Baldwin Bethune (d.1212) of Chateauroux, Reginald

Danmartin (d.1217) in Lillebonne and that he would find a bride for

Reginald Fitz Herbert (d.1201+). It is noticeable that in this

‘history' the land of Lady Helewisa was described as Lancaster and not the barony of Kendal. Of course it is further not correct that the king gave Lancaster

to Gilbert Remfry, as Helewisa's family had been constables there for

maybe 50 years. It was the barony of Kendal and the constableship

of Lancaster with Morhull castle

that came with the heiress who had the surname Lancaster. It is

also noticeable that The Marshall did not give up Cartmel, which was a

part of Lancaster lordship and had probably been given to him in the

expectation that he would marry Helewisa. When all is said and

done, The History of William le Marshal was a hagiography written to

paint him as a great, unfailing hero and not a bit of a dangerous and

dishonest bounder. Indeed many contemporaries thought him

anything but The Perfect Knight, but due to the Marshall's prowess in

personal combat, few were brave enough to say it out loud. A read

of David Crouch's excellent book on William Marshall, should put anyone

straight on that matter.

Although Gilbert Remfry was not a tenant in chief in 1166 at some point

before his death in 1220, a charter was entered for him to bring the

1166 survey up to date. Possibly this was done when the land was

granted to him by Richard I in 1190 as it includes the lands mentioned in Richard's charters. The full charter ran:

Lancaster

Charter of Gilbert Fitz Remfry

Gilbert Fitz Remfry, for 1 knight from his land of Westmorland and Kendal.

The same holds 1 carucate of land in Levens (Lesnes) with a fishery and 3 carucates of land in Farleton (Karlintone) and Beetham (Bescn') and 4 carucates of land in Preston Richard (Prestun) and 2 carucates of land in Burton in Kendal (Bertune) and 1 carucate of land in Hincaster (Heunecastr') and 1 carucate of land in Preston Patrick and 3 carucates in Lupton (Lutton) and a fishery which pertains to these lands by the service of a knight.

This is far more informative than the older, original 1166 charters

which only mentioned the owners of the knight's fees of various

baronies and not where they were.

In 1192 Hugh Bardolf and Hugh Bobi made the sheriff's return for

Yorkshire. At the end of this came the same sheriff's short

account for Westmorland. In this

he noted that the revenue of the county had been reduced by grants to

other people and for expenditure on 3 castles outside the barony - viz.

Kenilworth, Tickhill and Bristol. It was also noted that 2m (£1 6s 8d) worth of land had been given to Alan Valoignes (d.1195, Tebay),

£14 6s 4d from the land of Gilbert Fitz Remfry in Kendal and also

£8 18s 2d from the same land as well as 100s from the fishery of

Kendal. This makes it quite clear that Kendal had been operating

as a part of Westmorland before the grants of Richard I in 1190.

After King Richard had left for his Crusade in August 1190, Roger Remfry and his brood adhered to Prince John

(d.1216) against Richard's chancellor, Bishop William Longchamp of Ely

(d.1196). As a consequence, on 2 December 1191, the chancellor

ordered the excommunication of the 25 magnates who opposed him,

although he postponed excommunicating Prince John

himself until February 1192. Surprisingly of these 25 men 5,

Archbishop Walter Remfry of Rouen (d.1207), Roger Fitz Remfry (d.1196),

together with Gilbert (d.1220) and Remfry (d.1211) his sons, and a

probable cousin, Joscelin Remfry (d.1200+), belong to Gilbert's

family. However, the Remfry clan are definitely in the lesser

strata of the nobility when other excommunicates like the bishops of

Winchester and Coventry, earls Marshall, Essex, Salisbury and Mellent

and barons like Bardolf, Camville, Marshall, Basset, Vere and Ridel are

compared. With the overthrow of Chancellor Longchamp and his

brothers in 1192, things must have become much easier when Gilbert's

uncle, Archbishop Walter of Rouen (d.1207), took over the running of

the country for King Richard.

At Trinity (May/June) 1194 in Lancashire, the monks of Furness

complained that Gilbert Fitz Remfry had taken away from them 1,009

sheep, 100 fleeces and 88 lambs, against which they had a charter of

the king's made at Winchester

on 23 April 1194 [the Sabbath of the king's coronation] about having

peace and his liberty and so Gilbert's essoin was summoned to answer

this at court. This matter, which obviously concerned the

ownership of Furness Fells, could not be proceeded with at the time as

it was found that Gilbert was overseas. Presumably he was in

action in France where fighting was going on between forces loyal to Richard I

(1189-99) engaging those of King Philip Augustus of France

(1180-1222). The case with Furness was finally settled in the

king's court between 11 and 13 February 1196, when Gilbert and Helewisa

released to the monks all right of venison and hawks on the monk's side

of the fells and all claim to Newby (near Clapham, Yorkshire), in

return for which the monks granted them Ulverston (Olueston) for a yearly rent of 10s. The opening of the case on 11 February 1196 ran:

Between the Abbot and Convent

of Furness, plaintiffs, by William Leides, cellarer, and William

Lonsdale, put in their place to win or lose in the said Court, and

Gilbert Fitz Roger Fitz Remfry and Helewisa, his wife, tenants, by

Richard Marisco, clerk, put in their place, &c., respecting Furness

Fells (Montanis de Furnesio).

The abbot and convent have

granted to Gilbert and Helewisa, his wife, and to their heirs, that

part of the Furness Fells lying towards the West, which their

predecessors had in accordance with a concord and agreement, which was

made in the court of King Henry II as the charter which the monks have bears witness, by these bounds, to wit, from Elterwater (Elteswatra), by the valley to Tilberthwaite (Tildesburgthwait), thence by Yewdalebeck (Ywedalebec) to Coniston (Koningeston), and so into Coniston Lake (Thurstaine-watra),

thence along the bank [of the lake] to the head of Coniston Water, as

far as the headland which stretches [into the lake] below Rig, unto the

[River] Crake (Craic), thence by Crake unto the [River] Leven (Leuena); also from Elterwater over against the mountain by the stream which falls down from Wrynose Hawse (Wreneshals) unto Wreneshals, and so descending by Wreneshals into Borgerha [unidentified], and from Borgerha unto Duddon (Duthen), and thence descending by Duddon as far as the bounds of Broughton-in-Furness (Brocton)

extend; to hold of Furness abbey and of the said monks, in wood and

plain, in waters and fisheries, rendering yearly to the abbey and monks

20s for all service and custom. Moreover the abbot and monks

granted to Gilbert and Helewisa, and to their heirs, Ulverston (Olueston),

with all appurtenances, for 10s to be rendered yearly to the monks for

all service. These lands Gilbert and Helewisa and their heirs

shall hold of the abbey and monks in fee and inheritance, as freely and

quietly as the monks themselves hold of their lords, saving their

service of 30s for all service to be paid to them yearly on 14 August

(Eve of the Assumption of the blessed Virgin Mary). And Gilbert

and Helewisa his wife have granted and quitclaimed to the abbot and

monks of Furness, buck and doe, and hawk, in that part of the Fells

which belongs to the monks, and every liberty which Gilbert and

Helewisa themselves possess, freely and peaceably, and without claim

from them and their heirs, by these bounds, to wit, from Elterwater by

the dale to Tilberthwaite, thence by Yewdalebeck to Coniston and so to

Coniston Water, along the bank [of the lake] to the head of Coniston

Water to that bank which extends below Rig, unto the [River] Crake and

thence by Crake eastward unto Leven; also from Elterwater unto Brathay (Braitha), and from Brathay unto Windermere (Winendremer),

and by Windermere unto the [River] Leven, and so along the Leven unto

the sea. Further to the above, Gilbert and Helewisa rendered to

the monks and quitclaimed unto them, Newby (Neubi)

with all appurtenances, quit of all right and claim which they have

therein, or which belonged to them or their heirs, to hold henceforth

freely and quietly, and peaceably to possess it in the place of Gilbert

and Helewisa, and their heirs. If, however, anyone shall

hereafter seek to harass the monks respecting it [Newby], Gilbert and

Helewisa, and their heirs, will aid them to the utmost of their

ability, and maintain them in possession without cost. The 30s

which Gilbert and Helewisa owe yearly to the monks, for service for the

Fells and Olveston, they will pay on 14 August. Furthermore,

Gilbert and Helewisa granted to the monks a free road and passage for

themselves and all their belongings, by the way which leads from the

Abbey of Furness through Ulverston, and so through Crake's Lyth (Craikeslith)

unto the fishery of Crake, and so to their own lands whithersoever they

may wish, because the monks and their belongings sometimes used to

suffer molestation on that road.

This case had obviously exercised the monks of Furness a great deal,

for in their Coucher book the first royal confirmation of the agreement

by Henry II and its subsequent

reiteration for Roger Lancaster (d.1291) in 1282, are inserted as a

precis into the book before it really begins with the foundation

charter of King Stephen. The agreement of 1196 is then entered a few folios into the book.

In the meantime, Gilbert was charged scutage for the second army King Richard

led in Normandy [1194], but was quit of this as the king testified that

he had served in person. However, he was charged the same 20s for

the third Norman scutage in 1196 under Lancashire. This was

despite the fact that he had appeared with the king at Issoudun on 3 July 1195 and later at Rouen on 16 October 1197. He was also with the king at Winchester

on 20 April 1194 on his return from captivity. The reason for

this would appear to be that Gilbert had decided to make his peace with

King Richard after having sided with Prince John in his rebellion against King Richard in 1193. During the rebellion, Prince John had fortified his castles in the North. These included Tickhill and Lancaster.

It would appear that Gilbert supported his lord as constable of

Lancaster. There is an enigmatic entry in the Lancashire pipe

roll of Michaelmas 1194. This stated that amongst those who had

bought Richard I's forgiveness was Matthew Gernet who owed and paid 10m (£6 13s 4d) as he had been in the army of Kendal (Kendala) with the men of Earl John.

The fine meant that he could have seisin of his land returned.

Presumably it was Gilbert Fitz Remfry who had raised such an army of

Kendal for Prince John.

In the same section it was recorded that the abbot of Furness owed 500m

(£333 6s 8d) for having his charters and his liberties confirmed

as well as having his right against Gilbert Fitz Remfry in the lands of

Newby (Newebi) and Mutton Hall (Motton,

Killington reservoir) as well as having his chattels there. It

would seem from this that Gilbert's land of Kendal had reverted to its

status previous to the charter of King Richard in 1190 due to the disruption of the kingdom and his disloyalty to the king in the years 1192-94.

After this disastrous result of his revolt, it was necessary for

Gilbert to rebuild his position at Kendal. In 1197, he began

paying off the £100 proffered to the king and Archbishop Hubert

of York (d.1205) for his grant of £6 of land, acquittance from

cornage [a tax levied on horned cattle, cornu, where the tenant was

also obliged to give notice of enemy invasion by blowing a horn] and

other liberties according to the king's charter [of 1190]. As the

sheriff had ceased accounting for these lands in 1190 it shows that

this referred back to the 15 April 1190 grants. Of this renewed

proffer, he immediately paid £60 and then £40 the next

year, 1198. Despite this, at Michaelmas 1199 he was still charged

with £114 5d debts for his cornage and was forced to pay King John £100 and 2 palfreys for the remission of this debt and confirmation of his charters which included:

having gallows and ditch in the fee which he holds by the service of 1 knight's fee.... and that the agreement made with King Richard for cornage shall be kept and for holding in peace the land of Kendal which he had by the gift of King Richard.

Although the fine only seems to have been recorded in 1200, Gilbert had

paid his fine off by 1202. It is also noticeable that in 1197

Gilbert was referred to as Gilbert Fitz Remfry rather than Gilbert Fitz

Roger Fitz Remfry, as he had been previously been recorded. This

is probably because his father, Roger Fitz Remfry, had died the

previous year, 1196.

Under King John (1199-1216),

Gilbert Fitz Remfry eventually rose in the king's favour. Their

relationship seems at first to have been uncertain and, as has been

seen, in 1199 Gilbert proffered £100 to King John

for the confirmation of his charters and the boon of having gallows and

pit in his fee which he held of knight service in Lancashire and that

the agreement between him and King Richard

was validified, namely for his acquittance of cornage and for holding

his land of Kendal in peace - which fee he held by the gift of King Richard. For this fine Gilbert was quit of £7 3s 1d for the farm of Westmorland

for 1195, of £21 9s 3d for 1196, of £14 6s 3d for 1197, for

£14 6s 2d for 1198, £28 7s 10d for 1199 and finally

£28 7s 10d for this year, the total sum being £114

5d. The charter was actually enrolled on 26 April 1200 at Portchester.

Gilbert was also acquitted scutage on his 2 fees for this year, which

probably means that he campaigned in France with his king.

During 1201 it was recorded that Gilbert owed 30 marks (£20)

under Lancashire for his 3 knights fees in the honour of Lancaster and

2 in Westmorland. He also owed 30

marks (£20) for his misdeeds in the forest as was heard before

Osbert Longchamp in Lancashire. Gilbert was also quit by royal

writ of 2 and then 1 fee's worth of scutage in Berkshire in 1201 and

1202. Around the same time his son and heir, William Fitz Remfry,

was married to Agnes Bruce, the pair being sued by the abbot of

Leicester, who held rights in Kendal barony, on 13 October 1201.

Gilbert's favour under King John

is shown when he was made sheriff of Lancashire in 1205, an office he

held possibly until 1217 when Earl Ranulf of Chester (d.1232) was

appointed. For the first 8 years of his term, Adam Fitz Roger is

recorded as Gilbert's custodian or deputy in Lancashire. What is

certain is that there is no record of King John

revoking Gilbert's commission of being sheriff, right through the war

which ended his reign, although Gilbert obviously rebelled or failed to

acknowledge Henry III before

1217. The act of making Gilbert sheriff is quite informative as

it listed the places where Gilbert held lands on 25 April 1205:

the king to all his faithful men in the county and honour of Lancaster

telling them that he had given custody of the county and honour to

Gilbert Fitz Remfry and that they therefore were to be intendant upon

him.

The sheriffs of Norfolk and Suffolk, Northamptonshire, Lincolnshire and

the bailiff of the earl of Chester - all places where the Remfry

estates lay - were therefore to be informed of this. One of

Gilbert's first acts as sheriff was to give 30m (£20) of land in

his bail to King Reginald of Man as well as to make a charter to this

effect, the land being given to Reginald for his homage and service to King John.

As baron of Kendal or sheriff, Gilbert occasionally attended the king

in person. On 5 February 1207, he, Earl Geoffrey Fitz Peter of

Essex (d.1213) and William Briwere (d.1226) were with the king at Salisbury

when they witnessed a royal writ. Gilbert was still with the king

on 10 February at Oxford. Further signs of favour were shown to

Gilbert when on 17 February 1207 he was given custody of Alan Fitz

Count's lands in Watham, Keles/Relleg and Brikesl/Brickesleg.

Gilbert then became involved in the settlement of the lands of Theobald

Walter (d.1206), who had been lord of Amounderness and Preston in

Lancashire as well as baron of Nenagh

in Ireland. Consequently on 2 March 1207, the king sent Robert le

Vavasour [Theobald Walter's father in law] to carry letters to Gilbert

Fitz Remfry concerning the heir of Theobald Walter (d.1206).

Gilbert did have a slight link to Theobald, which would today be

regarded as very tenuous. Through his wife's mother, Helewisa

Stuteville (d.1228+), Theobald had been the husband of the

stepdaughter, Matilda le Vavasour (d.1225+), of the stepdaughter,

Juliane Multon (d.1212+), of the half sister, Ada Morville

(d.bef.1239), of Gilbert Fitz Remfry's wife, Helewisa Lancaster

(d.1213+). At this time religious unions were regarded as making

the family link direct as if it was a blood line. Whatever the

case of Gilbert's involvement in this, the death of Theobald had many

barons claiming custody of parts of the carcass of Theobald's

barony. In this case, Gilbert received the custody of Theobald's

heir, another Theobald Walter (d.1230).

Royal favour continued to be shown to Gilbert, with 5 tuns of wine

being sent to York on 14 August 1207 for his use in Lancashire and

Derbyshire. On 20 and 21 August 1208, King John stayed at Kyrkebi in Kendale

on his way south from Carlisle. As the castle most likely existed

at this time, he probably stopped there. In 1209 Gilbert fined

for 5 palfreys to have Newby manor which was previously held by Ralph

Soulis, the lord of Scottish Liddel

who had been assassinated in 1207. The 2 had made a concord

together, probably over this land, in 1200. At Michaelmas 1209,

Gilbert was appointed sheriff of Yorkshire, a post he held until 1213,

with Henry Redman acting as his custodian or deputy there. It was

around this time that Gilbert's court formed at Kendal to hear a

release of land to Gilbert in Lancashire by Matilda the daughter of

Elias Stiveton in return for 7m (£4 13s 4d). This was

witnessed by the men of Gilbert's court who would appear strongly in

the cause between him and King John in 1215. They were Lambert

Bussy, Adam Fitz Roger [Yealand], Gilbert Lancaster, William Windsor,

Roger Burton, William Fitz Waltheave, Gamel the forester, Richard

Arten, Benedict Gernet and Ralph Stiveton, togther with the 2 religious

brothers, Luke and John.

In June 1212, King John ordered

a great inquest to be made into the lands given and alienated in

Lancashire. Included in this was the Remfry barony. Here it

was recorded that Gilbert Fitz Remfry held 1 knight's fee in Lancashire

and that William Lancaster (d.1184) had given 5 carucates of land in

the 2 Ecclestons (Eccliston) and Larbreck (Lairbrec), which was now held by 5 named men. Similarly William had granted land in Forton, Halecat (Halecath), Catterall (Caterhale), Windermere (Wynomerislega)

and Crimbles. This William's father, William Fitz Gilbert

Lancaster (d.1170), had granted land in Cockerham to the cannons of

Leicester as well as land in Ellel (Elleale), Scotforth (Scotford), Lancaster, Carnforth (Carneford) and Ashton (Eston). Later under Lonsdale it was noted that Adam Yseni had given 5 carucates of land in Whittington (Witington - just south of Kirkby Lonsdale) to Gilbert Fitz Remfry. At Domesday this land, which included Newton (Neutune) and Thirnby (Tiernebi),

was valued at 10 carucates, but this figure, like many other Domesday

assessments, had been halved. The land was later held with

Yealand for five twelfths of a knight's fee from Kendal barony.

On 16 August 1212, Brian Insula (Lisle, d.1234), the archdeacon of

Durham, Philip Ullecot (d.1221), Gilbert Fitz Remfry and William

Harcourt (d.1223) were ordered to supply all the oxen and cows they

could to the army forming at Chester where the king was going to from Nottingham. The 1212 Welsh campaign proved abortive, but on 3 September 1212, when King John was at Durham, he wrote to his bailiffs of the sea ports of England letting them know that his ships, with Archdeacon W. Wrotham of Taunton,

had been sent to Gilbert Fitz Remfry with 80 tuns of wine ‘were

to be free and without impediment as they pass through your bails for

this one time only'. This, the best wine, was to be shipped from

Portsmouth to Scarborough castle where

Gilbert was in charge of the work being undertaken there for the

king. Quite clearly Gilbert was seen as totally loyal to be

granted charge of such a formidable northern castle as Scarborough where the king sent him 6 carrates of lead for ‘covering our tower of Scarborough'

on 7 September 1212. It is a pity that no such instructions have

survived for anything Gilbert may have done at Kendal castle.

On 15 November 1212, Gilbert was one of many barons told to arrest all

the ships found in his ports. The next year the king wrote to

Gilbert on 25 February 1213, telling him that he had given Robert Percy

custody of Yorkshire and that he was to hand the county over to him

freely. Three months later, around 23/25 May 1213, Gilbert was

amongst 12 named members of the baronage of England who had been

informed of the king's negotiations with the archbishop of Canterbury

and the cardinals, which were to bring about a reconciliation with the

pope and who had pledged to support this. Gilbert continued the

year being sent instructions by the king, one of which included his

holding of the prisoner, Fukeletto, who had been captured at Dieppe and was held at Scarborough. On 21 July 1213, Gilbert Fitz Remfry, together with the archdeacon of Durham and Philip Ullecot were ordered on seeing the king's letter to take all the fees and tenements of Eustace Vescy [Alnwick]

into the king's hands. This again shows that Gilbert at this time

was seen as a major royalist power in the North. At some time,

probably during 1213, the archbishop of Canterbury and the cardinals of

Rome, Earl Geoffrey Fitz Peter of Essex, Count Reginald Dammartin of

Boulogne, Earl Ranulf of Chester, Earl William Marshall of Pembroke,

Earl William Warenne, Earl William of Arundel, Earl William Ferrers,

William Briwerre, Robert Roos [Helmsley], Gilbert Fitz Remfry, Roger Mortimer [Wigmore] and Peter Fitz Herbert [Blaenllynfi]

were informed of and asked to firmly observe the peace now made between

the king and the English church. Presumably this letter was sent

around 15 May 1213 when the peace was made at Ewell near Dover.

This was followed on 31 October 1213, by various aristocrats being

ordered to complete and keep the peace between the king and the

Anglican Church and do nothing against the king without the pope's

advice. These men included the bishops of Norwich and Winchester,

Earls William of Salisbury, Geoffrey Fitz Peter of Essex, R of

Boulogne, Ranulf of Chester, William Warenne, William Marshall of Pembroke, Roger Bigot of Norfolk, William Fitz Alan of Arundel, William Ferrers and Saer of Winchester and the nobles Roger Fitz Roger [Warkworth], William Briwere (Brigerte), Robert Roos [Helmsey], Gilbert Fitz Remfry [Kendal], Roger Mortimer [Wigmore], Peter Fitz Herbert [Blaenllynfi], and William Aubigny.

It was in 1214 that royal favour began to desert Gilbert, who had

already been removed from the office of sheriff of Yorkshire in

1213. On 8 February 1214, the king ordered the baron of Kendal to

hand the custody of the son and heir of Theobald Walter over to Bishop

Peter of Winchester. Similarly on 25 April 1214, Gilbert was

instructed to give all the lands and tenements of Robert Thurnham

(d.1211) which he had in custody, over to Bishop Peter and that Peter

Mauley, who would marry Isabella the daughter and heiress of

Robert. This order was reiterated on 23 May 1214, when the king

restated that he had given to Peter Mauley the daughter and heir of

Robert Thurnham ‘to take as wife with all her hereditary'.

Gilbert was therefore ordered to hand all the lands and tenements he

had in custody over to Master Revell and William le Poher who had been

sent to take over these lands on behalf of Peter. The king was

also becoming increasingly paranoid - and perhaps with good

reason. On 16 August 1214, he wrote to various magnates including

Gilbert Fitz Remfry informing them that he was sending Thomas Erdington

and Henry Vere with various commands for them as he was unwilling to

set his instructions in writing and that more messengers are on their

way over the sea. Consequently the named barons were instructed

to take note of what they will be told, even if it came from Thomas

alone and that this was to be done ‘for the protection of our

castles and our body. Despite this letter indicating that Gilbert