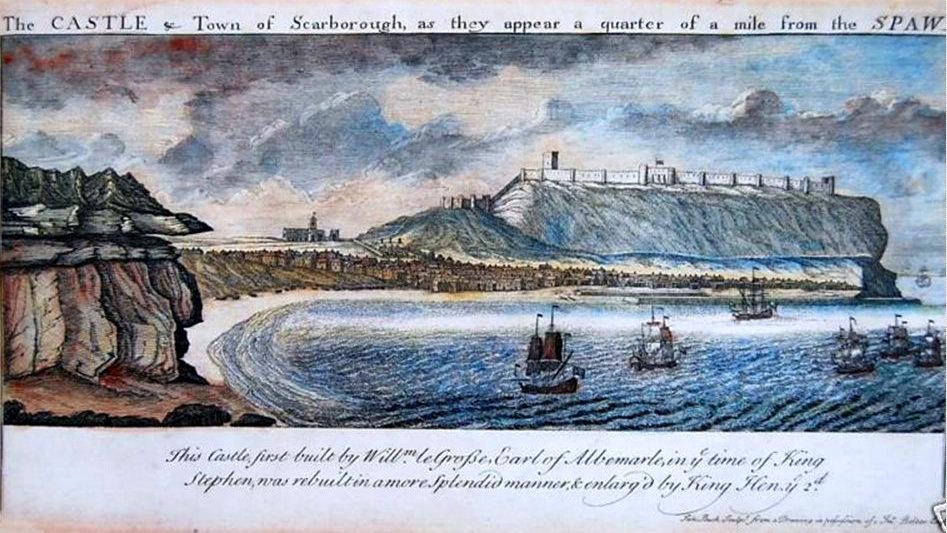

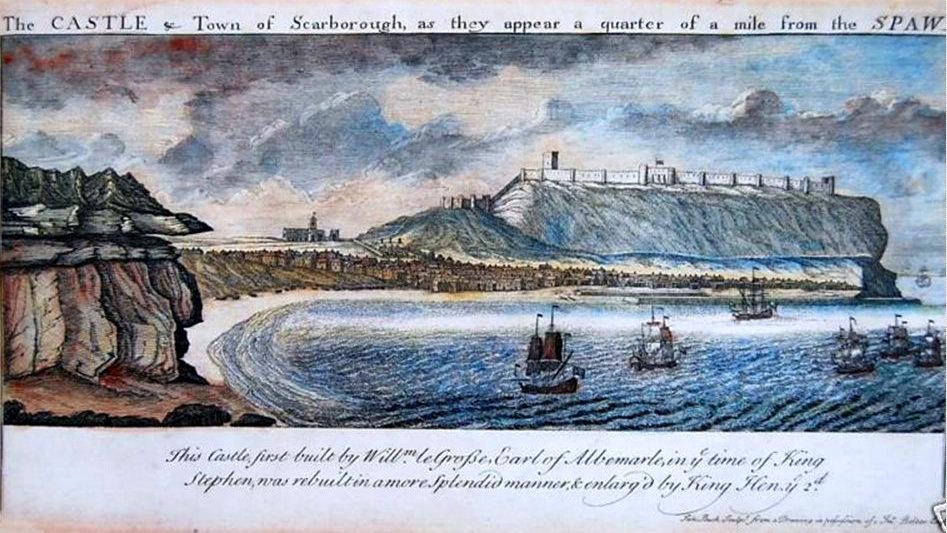

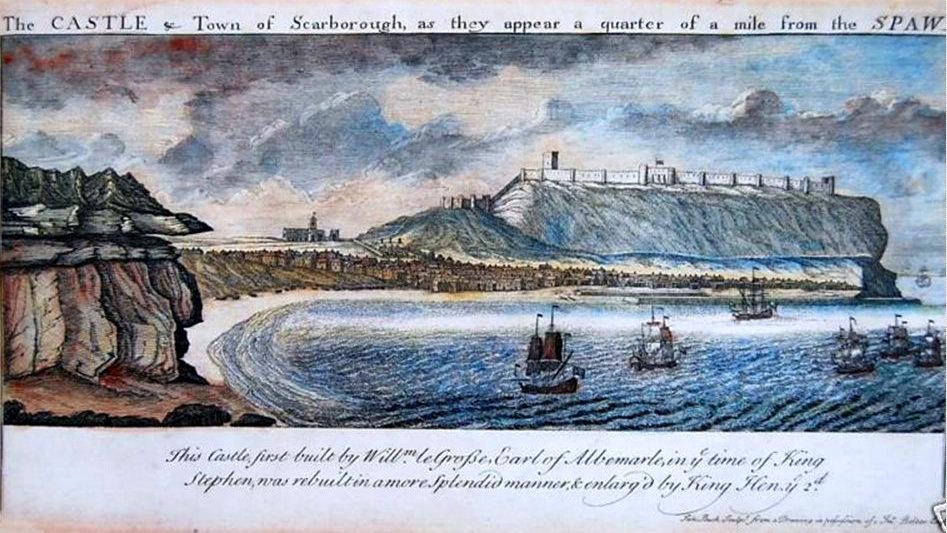

Scarborough

Scarborough castle stands on a prominent craggy plateau

jutting out

into the North Sea. It seems to have been occupied since the

sixth century BC although fragments of Beaker pottery found there may

date back to 2,100BC. Other items found on the headland

included

bronze axes, swords and jewellery. The pottery

sequence

excavated shows continuing usage and presumably settlement into the

Roman era. Certainly the position commands the chief shelter

between the rivers Humber and Tees and as such would have been a

trading harbour from the earliest of days. As such it may

have

had something in common with similar ancient headland sites, viz.

Tintagel.

The Romans built their own ‘castle' to command the bay and

some

of its foundations can still be seen on the eroded edge of the

headland. This ‘castle' is often wrongly described

as a

signal tower, though its precise purpose is unknown, it is certain that

they could not have been inter visible to other ‘watchtowers'

along the Yorkshire coast. Therefore these structures seem

best

to be regarded as stand alone castles in the true sense of the word,

protecting the coast from seaborn raiders, rather than signal stations

or fortlets linked to the late use of Hadrian's Wall. It

should

also be noted that the Emperor Diocletian (284-305AD) was building what

we would term castles as early as the beginning of the third

century. A good example of one of these still stands at Qasr

Bashir in Jordan.

Similar late Roman fortifications to Scarborough were constructed along

the coast at Huntcliff, Goldsborough, Ravenscar, Filey and possibly

Seaton Carew and Whitby. Other ‘stations' are

postulated

down the west coast too, while the still standing fort at Alderney

Nunnery is virtually identical in plan, although a third

larger.

Two German examples are also similar, Asperden and Moers Asberg, while

Ladenburg, Engers and Mannheim-Nckarau also bear

similarities.

The purpose of these Yorkshire ‘stations' seems to have been

to

guard the coasts against sea raiders who came to dominate the North Sea

in the third and fourth centuries AD. Further south the Saxon

Shore Forts were built far more powerfully to protect the more

prosperous lands of the south. Good examples of these can be

seen

on the east and south coasts at Burgh, Richborough, Lympne, Pevensey

and Portchester. Similar forts in the west exist at Cardiff

and

Caer Gybi. The smaller ‘signal stations' are

reckoned to be

later than the Saxon Shore Forts and probably belong to the latter half

of the fourth century, with arguments occurring as to whether they were

built by Theodosius, who restored Hadrian's Wall after the 367

Conspiracy, or by the rebel Emperor Magnus Maximus (d.388).

The series that includes Scarborough don't seem to mesh into the

defences of Hadrian's Wall and it is possible that they were stand

alone castles protecting the coast. This assumption is

somewhat

strengthened by the fact that another such castle has been found on the

Exmoor coast, overlooking the Bristol Channel and therefore commanding

the Severn Estuary. Others have been postulated in East

Anglia at

Caister by Yarmouth, Corton, Stiffkey and Thornham. Coin

evidence

suggests that Scarborough ‘station' was built around 370 AD

and

abandoned or destroyed after a relatively short life of a generation or

2. Early excavators thought they found evidence for several

of

these forts being overrun and destroyed in the ‘early' fifth

century. However, the view now is that they may have become

mausoleums as did other sites on the Rhine frontier. Sadly in

Britain at this time the coin evidence becomes rare and uncertain.

Well after the fifth century, the entire top of Scarborough hill was

fortified enclosing a rhomboid area which is now roughly 1,000' by

800', but before sea erosion was much larger. During the late

tenth century a settlement is claimed to have stood here when Knut and

Harold the sons of Gorm landed here, defeated Adalbricht Fitz Adalmund

at ‘Skardaborg' and marched on York. Possibly this

is a

folk memory of 2 Viking brothers, Thorgils and Kormac. As an

excavation in 1921/25 discovered the ruins of a chapel built into the

Roman station ruins which was dated by them to pre-1066, the building

of this chapel is often attributed to them. It is then

claimed

that this chapel must have been destroyed in the mid eleventh century,

possibly when Harold Hardrada and Tostig Godwinson invaded England on

their way to the battles of Fulford Gate and their deaths at Stamford

in 1066. It was recorded that the Viking army landed at

Cleveland

and devastated the district. The fleet then moved down the

coast

to Scarborough and met stiff resistence from the townsfolk.

Consequently they seized ‘the cliff' which appears to have

been

undefended and made a huge bale of hay which they set alight and then

tossed the burning brands down the cliff and into the houses, burning

them ‘one house after another, after which the whole town

gave

itself up'. If such a story is accurate it suggests that

there

was no castle on the hill before 1066, but there was a town below it

that was not totally destroyed or recorded in Domesday.

The above ‘history' sits rather uncomfortably with the

excavated

‘history' of the chapel on top of the Roman

station. This

is thought to have been the chapel of Our Lady first hinted at in 1331

when the parson of Our Lady was involved in a plea to Edward III on

behalf of the abbot of Citeaux concerning a grant made by King Richard

I in 1198. The excavated chapel is therefore

thought to be the

chapel existing in Scarborough castle which is referred to by the

Cistercians from 1198 onwards and described as the chapel of Our Lady

in 1538, confirming its location. The church

site on the Roman station was lost before excavation in 1921/25

uncovered the slight ruins. Excavation suggested that at some

point after 1086 the supposedly destroyed hilltop church was rebuilt as

the highly decorated chapel of Our Lady. Possibly this was at

the

same time as the cliff was fortified, although it should be noted that

Scarborough does not appear in the Domesday Book which would suggest

that there was no settlement here yet and the Viking history of the

site is fable. William Newburgh (1136-98), writing about

1196-98,

gives the most detailed story of the castle's foundation.

Concerning the site of

Scarborough castle

A rock simultaneously of stupendous height and

extent, precipitous

and nearly inaccessible on all sides due to cliffs the sea breaks upon

which surrounds the whole, except for at a narrow gorge which opens to

the west. On top is a heavenly plain, beautiful and grassy,

more

than 60 acres in extent, with a fountain of fresh water flowing from

the rock. At the very entrance, which cannot be climbed to

without effort, is situated the royal tower and under the same entrance

the town begins, spreading both to south and north, but having its

front to the west. It is fortified on this front by its own

wall,

but on the east by the castle rock; while both sides are washed by the

sea. Indeed, this place above mentioned, Earl William, when

he

was able to possess much of the county of York, contemplated

constructing a convenient castle, so he aided nature with lavish works,

surrounding the whole plain of the rock with a wall and fabricated (fabricavit) a tower

at the narrow gorge, which by the process of time had collapsed, the

king ordered a great and magnificent fortress (arcem) to be built (aedificari) there.

The above ‘history' begs more questions than it answers when

compared with the known events in east Yorkshire during the reign of

King Stephen (1135-54). Firstly, it should be noted that it

categorically does not say, as a certain government agency would have

it, ‘William of Aumale was responsible for enclosing the

plateau

of the promontory with a wall and erecting a tower at the entrance, on

the site of the present keep'. However, dismissing modern

hearsay, it should be borne in mind that as Newburgh had been born in

Bridlington, only 16 miles from Scarborough and spent the bulk of his

life at Newburgh priory only 33 from Scarborough, what he has to say

about the place is surely relevant. Taken literally Earl

William

fortified 60 acres of the rock with a wall and built a tower at the

entrance. Then comes the crucial clause of the sentence

concerning the keep, ‘which by the process of time had

collapsed'. The Latin verb used for Earl William making his

castle is fabricavit.

Although this generally means build, it is an unusual word to use with

castle works. It should therefore be strongly noted that the

root, faber,

can also mean

construct, fashion, forge or shape. The latter three verbs

could

obviously apply to a pre-existing structure, while his words about King

Henry II, ‘the king ordered a great and magnificent

fortress to

be built there' says absolutely zero about him building the keep that

he is often claimed to have built by modern

‘historians'.

The verb aedificare

can mean to built, erect, establish, create or frame, while the noun arx

generally means stronghold, castle, citadel, fortress or acropolis

rather than tower or keep. More will be said of this when the

time comes to discuss the Henrician building phase of Scarborough.

Earl William of York (d.1179), otherwise known as Count William of

Aumale, was the son of the Crusader, Count Stephen of Aumale and

Hawise, the daughter of Ralph Mortimer of Wigmore. At the

time of

William's death in 1179 he was lord of the castles of Skipsea in

Holderness as well as just possibly the 2 lordships of Skipton and

Cockermouth, through his marriage to the heiress, Cecily Romiley

(d.1188). After his death she referred to herself as Countess

of

Aumale and lady of Copeland. On the eastern bounds of

Normandy

Earl William held the county of Aumale. During the Anarchy

(1136-54) he had been sheriff as well as from 1138, earl of

York.

Up until the coming of King

Henry II into the North in December 1154 he

was also lord of Scarborough castle.

William had been an early supporter of King Stephen

(1135-54) and after

a good showing at the battle of the Standard on 22 August 1138, where

Orderic described his as the English leader, was made earl of

York. The earl pressurised the electors of York to appoint

William Fitz Herbert, a nephew of King Stephen, as archbishop of York

in January 1141. However, before this could be confirmed, on

2

February, William was one of the 7 earls who fled the battle of

Lincoln, leaving King

Stephen to his fate. With the king restored

at the end of 1141 Stephen moved into Yorkshire in April 1142 and

prohibited the tournament that was to take place between Earl William

and Earl Alan of Richmond (d.1146). That such a tournament

was

planned suggests animosity between these 2 royalist magnates.

Earl Alan died in 1146, but this hostility seems to have continued

under his son, Conan (d.1171). On 24 July 1147, the electors

of

York were forced to meet at Earl Conan's castle of Richmond due to the

hostility of Earl William at York. Certainly much hard

fighting

was to occur in Yorkshire before the reign was out. Around

this

time, some years after 1144 according to Newburgh, Earl William

attacked Earl Gilbert Gant (d.1156), apparently attempting to seize the

shrievalty of Lincoln from him. However, the battle went

against

William and Gilbert burned Hellewell, slew William's brother and seized

Castle Bytham from him. In reply Earl William destroyed

Hunmanby

castle, while he was apparently allied with Eustace Fitz John (d.1157) of

Alnwick.

Regardless of these sketchy events, in the confused politics of

Yorkshire, William was generally King Stephan's man, just as his uncle,

Hugh Mortimer of Wigmore (d.1181), was a royalist in the Welsh

Marches. William remained loyal to King Stephen to

the end of the

reign, but, when told to return the royal castle of Scarborough to the

new King Henry II,

he affronted, just like his Uncle Hugh Mortimer was

over the possession of the royal castle of Bridgnorth. The

story

is told by the chroniclers. Within a month of his accession

on 19

December 1154, King Henry marched against Earl William and brought him

to submission at York. Again according to Newburgh:

the

king proceeded beyond the

Humber and summoned Earl William of Aumale, who under King Stephen had

been more a king there, to surrender [the royal towns and villages...

extorted from King Stephen] to the weight of his authority.

Hesitating a long while, and boiling with indignation, he at last,

though sorely hurt, submitted to his power and very reluctantly

resigned whatever of the royal domains he had possessed for many years,

more especially that famous and noble castle called Scarborough...

Despite Newburgh's earlier implication that William had first fortified

Scarborough rock, the above passage suggests that a royal castle may

have stood here before 1135. In effect Newburgh leaves the

question as to who built Scarborough castle unanswered and in all

likelihood, he had no idea of what had happened there ‘in

time

beyond memory'. What is certain is that King Henry II

(1154-89)

granted Earl William the important royal manor of Driffield, worth

£68, some 20 miles south of Scarborough. Perhaps

this was

done in compensation. Certainly in 1158 William paid Henry

100m

(£66 13s 4d) of his debt and the king pardoned him his

remaining

100m (£66 13s 4d). This suggests an element of

royal favour.

Although Earl William didn't follow his uncle, Hugh Mortimer (d.1181),

into all out active rebellion, he didn't show much favour to his new

king and his defence of Aumale castle against Henry's enemies in 1173

was thought deliberately treasonable. On the count of

Flanders

attacking the town it was rapidly overwhelmed, despite its strong

garrison. With no apparent resistence Earl William was taken

captive. He then surrendered not only Aumale castle with its

royal garrison, but all his castles to the rebels as ‘he

wavered

in his adherence to the elder king' and it was ‘certainly

believed that he was in collusion with the count of Flanders'.

What could have caused such animosity? The fate of

Scarborough

castle is a possibility. If the castle was founded by Earl

William during the Anarchy (1135-54) he may have thought himself

entitled to greater compensation than a single manor.

Alternatively the castle may have been on royal land and Earl William,

as sheriff of Yorkshire, had merely upgraded a previously existing

royal stronghold built at some point after the Norman Conquest of

Yorkshire. Without further evidence it is simply impossible

to

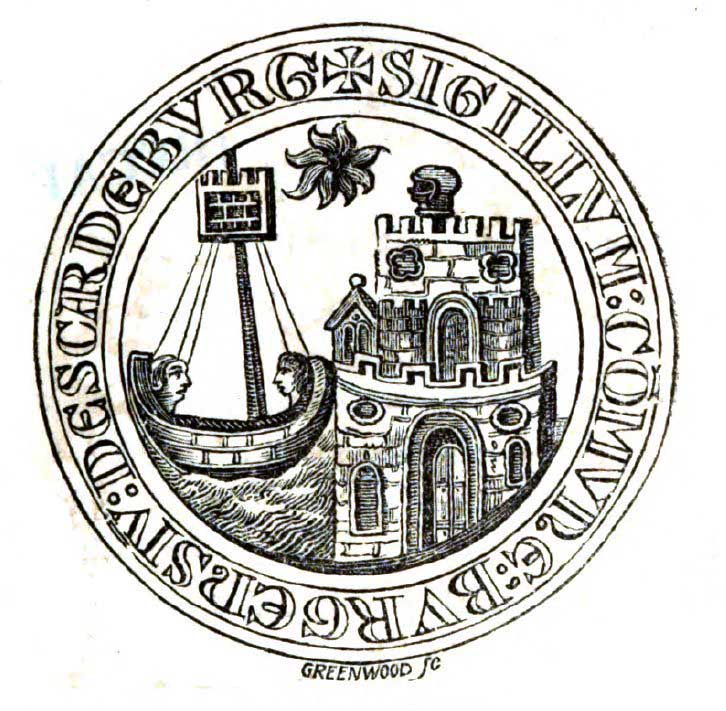

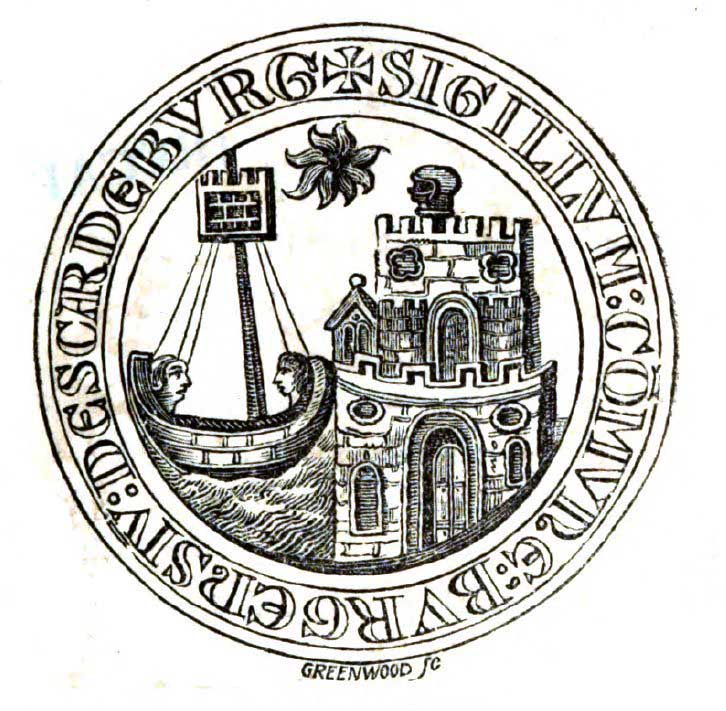

say, although the twelfth century seal of the burgesses of Scarborough

has a representation of the castle on it which shows 2 Romanesque

gateways leading up to the square keep. The outer gate is

decorated with 2 windows and 2 round windows below the battlements.

The keep itself is recorded with 2 quatrefoil windows in a

similar position, while looking out to sea might just be a

representation of Our Lady's Chapel.

For the purposes of the following discussion, it is to be presumed that

the above figures amounted to the total spent at the castle and that

they were correctly allocated, which seems possible considering the way

the works were divided in 1159. If correct, the

£131 spent

on the keep, mainly in 1159-60, was comparable to the £131

recorded as spent on the building of the 120' diameter White Castle

inner ward curtain in the period 1185-87. Similarly

£135

was recorded as spent on the 40' square Peak keep in 1175;

£64

16s 11d on Bridgnorth keep in 1169-71 and £101 3s 4d on Bowes

keep in 1179 and 1187 - the works recorded as being spent on just the

castles in each case not being included in these figures. At

first glance these figures may appear reasonable, yet £102

18s

11d was spent on Canterbury keep in 1173-75 and although Canterbury is

a much larger keep this figure should be a warning.

Similarly,

between 1182 and 1186, the records show £2,715 9s 10d spent

on

Dover keep, while another £1,015 6s 9d was spent on both

castle

and keep in 1182 and 1187. Further £2,592 7s 1d was

recorded as spent solely on Dover castle in the period

1180-88.

Although Dover keep is a superlative structure, its cost factor of 30

times higher than the roughly £100 recorded as spent on the

keeps

of Bowes, Bridgnorth, Peak or Scarborough, makes a mockery of using

pipe roll figures to demonstrate the founding date of keeps.

Either the figures simply cannot make up the entire expenditure on the

keeps, more of the keeps existed when work began, or

the figures are incomplete with more expenditure occurring at the keeps

than is recorded in the pipe rolls. Indeed a mixture of one

or

even all of these are possible at each, individual site.

For a nearer compatible keep in size to the above 4 of Bowes,

Bridgnorth, Peak or Scarborough, it is possible to turn to Newcastle on

Tyne keep. This was recorded as costing £1,174 10s

11d in

1172-77. Again was Newcastle keep really over 10 times more

expensive than the smaller keeps? Another example used to

bolster

the idea that Henry II built these small keeps is the construction of

the 90' tall Orford keep. This is traditionally dated to

between

1166 and 1173 when £1,689 17s 9d was recorded as being spent

on

the castle in the pipe rolls. It should again be noted that

all

of this was placed against the Orford castle works with there being no

mention of the polygonal 45' diameter tower, although it is alleged

without the slightest contemporary evidence that the keep was built at

this time. As Scarborough keep was 56' square and 90' high

that

would have given it a rough volume of 282,000 cubic feet. By

comparison Bowes at 80'x60'x50' would have been a similar 240,000 cubic

feet, Bridgnorth at 38½'x35'x70' would have been only 94,500

cubic feet, similarly Peak at 40'x40'x60' would have only been 96,000

cubic feet. As all of these keeps were allegedly built from

new

and paid for by Henry II (1154-89), the price tags of £146,

£64 and £131, for Bowes, Bridgnorth and Peak, seem

far too

low when compared with Newcastle at 62'x55'x80', giving 272,500 cubic

feet for £1,190 and Dover at 98'x95'x80', giving 744,500

cubic

feet for over £3,000. The internal cubic volume of

Orford

keep would have been about 145,000 cubic feet for an unrecorded cost

allegedly amongst the £1,600 spent by Henry on the

castle.

Quite clearly the figures supplied in the pipe rolls cannot be used as

the cost of building certain or indeed any structures in any

fortress. Surely what is being recorded here is the total

expenditure on a site which could range from well digging to wallwalk

making and from keep construction to the making of new castle gates or

bratticing. Consequently the building of any of

these keeps

may or may not be included in the costs recorded and although the

entries referring to work on towers probably means the keep, it must be

accepted that this could just as well refer to refurbishment of

pre-existing keeps and that these expenditures were often lumped

together with the refurbishments of the enceintes and most often

explicitly with the building, repair or amendment of the houses within

the fortresses. Expenditures made on castles show that it was

often the maintenance and amending of the castle houses that were of

primary concern to the governments of the day. The

maintenance of

the fortifications, except in time of war, seemed a less extensive

pastime, but more expensive when it occurred. The thirteenth and

fourteenth

century inquisitions at Scarborough certainly support such an

assumption

with more detailed descriptions given of the castle houses than the

actual fortifications.

Whatever was done by Henry II at Scarborough castle, the work must have

been both successful and long lived, for the fortress drops out of the

records from 1169 until 1175. There is no mention of it being

attacked in the war of 1173-74 with Earl William of Aumale (d.1179)

surrendering himself to the enemies of Henry II rather than fighting

early in the war. Otherwise he would presumably have led any

opposition to the royal garrison of Scarborough if any local discontent

had built up during the war in Yorkshire. Certainly the king

of

Scots failed to penetrate into Yorkshire in any strength and would have

been unwise to press as far south as Scarborough with powerful castles

left to his rear, viz. Prudhoe, Durham, Newcastle and

Richmond.

In the aftermath of the war the paltry sum of £2 was spent in

works on a gate and barbican in 1175. Just possibly these

needed

work as they were damaged in an attack in the foregoing war.

Further, the minor amount spent on them would suggest that either more

was spent elsewhere, the structures were mainly sound, or insubstantial

wooden works were repaired.

Ten years later Scarborough castle was in need of some minor repairs

which caused an expenditure of £16 7s 4d in 1188.

The reign

of Richard I (1189-99) saw early disturbances in Yorkshire and this may

have led in 1190 to Gilbert Lacy (d.1212+) being awarded £20

to

undertake the custody of Scarborough castle by the writ of the

increasingly hated chancellor, Bishop William Longchamp of Ely

(d.1197). In 1192 work was carried out on the castle well at

a

cost of £9 17s 3d. This was followed the next year,

1193,

with undefined works at the fortress costing, £10 10s

11d.

At this point a struggle occurred when Prince John (1166-1216)

attempted to seize England from his brother, King Richard

(d.1199). Towards the end of this insurrection, on 30 March

1194,

Hugh Bardolf (d.1203) was removed from his 2 year old shrievalty of

Yorkshire together with the constableship of the castles of York and

Scarborough as well as the bailiwick of Westmorland (which probably

included Appleby and Brough castles). At this point the

chancellor, Walter Remfry of Coutances (d.1207), made an offer for the

shrievalties of Yorkshire, Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire, but was

refused them. Scarborough castle instead with given to

William

Stuteville (Cottingham & Brinklow, d.1203). As a

royal castle

Scarborough had the minor sum of £2 5s spent on amending the

fortress in 1197. Finally, on 14 May 1198, King Richard

(1189-99)

granted Scarborough church to St Mary's abbey, Citeaux, a grant

elaborated on by his nephew, King Henry III (1216-72) in

1250.

Over 80 years later on 9 March 1284, an inquisition was held at

Scarborough on whether to demolish the old borough defences.

This

states that the old borough walls were standing in the time of King

John (1199-1216). Consequently they may have been built at

any

time before 1215 at the very latest. In 1284 a jury of 12

good

and honest men found that:

the

wall between the old and new

borough could not be thrown down without damage to the king, because,

as the annals relate, that wall, in the days of King John, when the

kingdom was depressed by many tribulations and dissensions, was an

obstacle and hindrance to the king's enemies, so that they could not

execute the injuries which many times they hoped to inflict upon the

king's castle and borough of Scardeburgh.

Moreover, when the

malevolent enemies of King Henry III, of happy memory, had arrived with

hostile intent to besiege the castle and borough, and intended to enter

easily within the said wall, they were impeded by it, though old and

partly destroyed, and often thwarted and repulsed by a ditch

surrounding the new borough; wherefore, if the wall be thrown down, the

inhabitants as well as strangers could easily enter the borough, to the

no mean damage and grievance of the king.

They also say

that the wall could not be thrown

down without annoyance to the burgesses, because the old borough is for

the greater part enclosed and strengthened by it. If it were

removed, the burgesses would have no power to resist the king's

enemies, who, a chance occurring, could more quickly consume and

pillage the borough. A further reason against its removal is

that

the king's enemies and depredators coming in hostile manner against the

borough, would find no obstacle until they arrived at the castle gates;

and so the whole town could be injured or even annihilated, and the

castle itself would be very greatly endangered, because open to siege

from a nearer point. Nevertheless, it would be advantageous

and

useful to the castle and borough if the burgesses could build a wall

over the ditch before mentioned, by the help and grace of the king, and

in place of the old wall quickly begin a new one; at which, when

completed, the burgesses, whether of the old or new borough, with

hearty union and mutual counsel could, if need were, unanimously oppose

and strenuously keep at bay the king's enemies and other malefactors

coming thither in hostile fashion.

No attack on Scarborough during the reign of Henry III (1216-72) is

recorded other than in this inquiry. Possibly the castle was

attacked in 1216-17 or in the troubles of 1263-66, but more likely this

was the burgesses adding a fiction to their desire to save their

borough walls.

King John, when perambulating the North, stayed at Pickering on 1

February 1201, before being at Scarborough by 3 February and moving on

to Egton by the 4th. He came back to the castle again during

his

campaign into Scotland early in 1216, staying at Scarborough from 12 to

13 February before appearing at Kirkham on the 15th. From the

start of his reign he had developed both Scarborough and Knaresborough

as major royal castles in Yorkshire, spending the surprisingly large

sum of £2,283 3s 10d on Scarborough. This was more

than he

spent anywhere else on any other castle in the kingdom.

Although

guide books claim where this money was spent, there is actually no

evidence as to what was done with it. Indeed some of this

cash

could even have been spent on the town walls.

At the start of the new reign in 1199 many Northern castles had work

done to them and included in this list was £2 15s recorded as

being used for amendments to Scarborough castle. On

29 March

1202, John Bully (d.1213) was given £33 for the custodianship

of

Scarborough as well as being allowed £14 to repair

the

castle. This £33 would appear to have been the

annual

stipend as Bully received the same amount the next year, 1203, as well

as an extra £33 for works at the castle. Two years

later in

1205 another £113 and £48 12s was recorded as

having been

spent at Scarborough. In 1206 the custodian's wages were

noted

for the last 2 years and another £68 15s 5d was accounted for

in

castle works. In 1207 the paltry sum of £8 15s 6d

was split

between Scarborough and Pickering castles, while in 1208 the more

respectable sum of £68 8s 2d was spent on Scarborough

alone. On 26 February 1208, Robert Vaux was made constable of

Scarborough and Pickering castles

It was after the Braose rebellion of Spring 1208 and the continuing

unrest in the kingdom that King John began the refortification of

Scarborough in earnest. In 1210, works at the castle cost

£620 1d. The next year, 1211, works at the castle

and on

the king's houses within were recorded at £542 6s.

Finally

in 1212, £780 6s 8d was allocated to the works and the king

ordered the keep roofed with 6 carets of lead which were to be supplied to Gilbert Fitz Remfry (d.1220) of Kendal who had charge of the work there. If such an amount

of

money had been spent on the keep and roofing in the reign of Henry II

(1154-89) it would definitely have been taken for granted that he built

the keep, not merely upgraded it! The king then proceeded to

munition the fortress with 600 bacons and 60 cow carcases, 14 tuns of

wine, 10 lasts of herrings, 40 loads of salt, 1,000 unfinished irons,

20 marks of corn and £10 of hay and turf at a cost of

£173

7d. King John, at nearby Tickhill on 20 September 1213,

ordered

his custodian to further stock the castle. It is obvious from

this that he was expecting trouble. The next year it was

recorded

that the custody of Scarborough castle, now held by William Duston,

went with a stipend of £50. Not long ago it had

been only

£33.

On 29 March 1215, the king ordered Geoffrey Neville (of Raby, d.1249)

to place 60 sergeants and 10 crossbowmen in the castle. On 5

July

the king sent them some pay of £19 17s 11d to Brian Insula as

well as £286 14s 7d through Geoffrey Neville. A

month later

on 11 August 1215, the king ordered William Duston to allow

‘our

loyal Earl William of Aumale' (d.1241) and his associates to be

received in Scarborough castle to take custody of the

fortress.

This Earl William, lord of Cockermouth and Skipton castles, was the

grandson of the Earl William le Gros who had died in 1179.

Despite these moves, the king obviously still felt the castle was

threatened over a year later for, on 30 March 1216, the king had sent

£100 to Geoffrey Neville (d.1249) to munition the castle and

buy

6 bone crossbows with quarrels. This was followed on 18 April

1216 with a payment of £105 17s 6d made to the knights and

serjeants in Scarborough castle under Geoffrey Neville.

Finally,

on 14 June 1216, Brian Lisle (d.1234) of Peak was ordered to send 100m

(£66 13s 4d) to Geoffrey Neville for the works he was

carrying

out in the king's garrison of Scarborough. All this

expenditure

proved fruitful and the castle never fell to the rebels, although the

inquest of 1284 mentioned above suggests that it might have been

attacked at this time.

After the death of King John on 19 October 1216, various works were

continued at Scarborough and Pickering castles, although the cost

wasn't accounted for until 25 May 1226. At this date the

Crown

recognised that it owed John Neville 1,000m (£666 13s 4d) for

the

strengthening and repairing of Scarborough and Pickering castles which

Geoffrey Neville (d.1249) had carried out. Presumably some of

this went on repairs to the keep and hall recorded in September

1224. Other elements of this large sum seem to have included

the

200m (£133 6s 8d) sent to Geoffrey Neville for his custody of

Scarborough and Pickering castles on 4 January 1225 and the

£50

sent to John Neville, in place of Constable Geoffrey Neville of

Scarborough, for the custody of the castles on 8 August 1225.

Towards the end of the year on 8 December 1225, a further

£200

was sent to Geoffrey Neville for the custody of Scarborough castle.

Quite clearly some of this sum was therefore spent on the

garrisoning and not the repair of the fortress.

On 3 May 1226, Robert Cockfield is first associated with Scarborough

when he was given £40 to repair the castle. Nearly

3 months

later on 23 July 1226, he was sent 100m (£66 13s 4d) for his

works at Scarborough castle. Presumably this was when the

Cockfield Tower was built at the southern apex of the castle as it

subsequently held his name. By September 1226 further repairs

had

been undertaken for a charge of £40 at Scarborough and

Pickering

castles as ordered on 3 May in the close rolls, while Geoffrey Neville

had received £200 for his custody of the 2 castles since 1220

and

a further £90 for works carried out in 1225 and

1226. Part

of this work may have been the re-timbering of the castle as 60 oaks

were ordered from the surrounding forests for the works and amendments

in the king's houses of Scarborough castle on 23 July 1226.

In September 1227 it was recorded that the houses, walls and other

things in Scarborough and Pickering castles had been repaired at a cost

of 50m (£33 6s 8d), while amendments to the houses had cost

£10 18s 4d. Another £14 5s 10d had been

spent on

castle works in both fortresses, while sundries totalled another

£15 12s 3d. The final allocation of funds in this

maintenance session came on 3 June 1228, when the sheriff of York was

allocated 60m (£40) to be spent by the king's order on the

castles of Scarborough and Pickering; with a further 100m

(£66

13s 4d) coming from the men of Scarborough for the works; and

£14

5s 10d in addition to the 160m (£106 13s 4d)

allocated.

Further 16m (£10 13s 4d) was allocated for the keeping of

Scarborough and Pickering castles for the year before Michaelmas 1226.

Work began on the castle again 10 years later on 3 December 1237 after

it had been damaged by ‘a tempest of wind'. The

instructions were to temporally repair the houses that were unroofed so

that they wouldn't be damaged further and then fully repair them in the

summer. Consequently £42 2s was spent on repairs to

the

keep leaded roof as well as the hall, chamber, chapel, bridge and other

buildings by Michaelmas 1239. However, the section of wall

that

had long ago slumped (pridem

corruit) was only ordered to be replaced on 20 June

1241. This was done by Michaelmas when the cost was recorded

as

£63 13s 4d. This was followed on 30 June 1242, with

an

instruction to the sheriff of York to spend £40 in repairing

a

bridge and a fissure in the castle. The same day the king

ordered

his justiciar of the forest, Robert Roos of Helmsley (d.1285), to send

the constable of Scarborough castle timbers to repair the castle bridge

as well as to make 3 gates. As a result that Michaelmas 1242,

it

was recorded that £40 had been spent on repairing the bridge

and

a breach in the walls as well as £2 10s on amending the

castle

houses. Early the next year on 27 January 1243, the sheriff

of

Yorkshire was allowed to spend up to £20 in making a tower

before

the gate of the king's castle of Scarborough. This he had

obviously half done by 19 July when the king allowed him to spend an

additional £20 in finishing the gate he had begun.

In that

Michaelmas' pipe roll it was recorded that the sheriff had spent

£40 on the gatetower as well as £5 in amending the

king's

houses in the castle. This does not appear to have been

sufficient to finish the structure as at Michaelmas 1245 it was

recorded that another £41 7s 3d had been spent on

‘completing the building of the great gateway of Scarborough

castle' and another £5 on amending the king's houses.

On 17

November 1250, the king granted to St Mary's church, the abbot of

Citeaux and the parsons of Scarborough church of the chief mansion with

the enclosure made by them in Scarborough town concerning which a plea

had been made at the king's court, by rendering 4s yearly.

This

was elaborated on 20 November when the king added that he was granting

to Citeaux for the souls of kings John and Richard, of the gift made to

them by King Richard [in May 1198] of Scarborough church with all its

chapels and appurtenances, to aid the abbots for their expenses for

their 3 days at the general chapter at Citeaux; and that any surplus

should be expended for the use of the abbey. Further, it was

the

king's wish that the abbey should hold Scarborough church with all its

chapels including the chapel within the castle... and that no one

should set up a chapel or altar in the parish.... It has been

stated that this referred to the chapel on the Roman station, but it is

not clear from King Richard's grant or this, that the chapel was not

the one in the keep forebuilding.

On 14 June 1253, keeper John Lexington/Laxton (d.1257) of the king's

manor of Pickering and Scarborough castle was allowed up to

£100

to repair the buildings, bridges and walls of Scarborough castle as

well as maintain the king's [buildings?] of Pickering castle.

Five years later in 1258, when Henry III's mismanagement of his kingdom

finally pushed his overtaxed barons to take control of the kingdom, the

custodians of 21 royal castles were changed; the reformist, Gilbert

Gant (d.1274) being sent to Scarborough on 29 March 1259. The

next year on 26 August 1259, the king ordered the sheriff of York to

repair the defects of the buildings, walls, keep, turrets and bridges

of Scarborough castle ‘where absolutely necessary out of the

issues of the county'. Despite this, nothing seems to have

been

done, but the castle was attacked before 11 February 1260, presumably

by royalists. On that day the king asked for a jury to

enquire

into:

who

came armed to Scarborough castle and the

trespasses they committed against the king as well as against Gilbert

Gant, the king's constable of that castle, after he had the keeping

thereof....

Soon afterwards, on 19 May 1260, Gilbert was ordered to relinquish his

charge to the reformist justiciar, Hugh Bigod (d.1265). Then

the

sheriff of York was asked to visit Scarborough castle to determine what

state it was in when surrendered by Gant to Bigod.

Consequently,

on 20 May 1260, his inquisition determined that:

The

large hall, vaulted chamber and garderobe are

uncovered in many places and need great repairs. The kitchen

with

the tresaunce are almost unroofed, while the stables have been

completely uncovered, the manger is broken and one guesthouse

collapsed. Further the walls of the mill house are broken and

there is no mill there. Truly the granary is weak.

The hall

in the keep ward is completely unroofed and some of the timbers are

broken and it threatens to ruin. Also the 2 bridges of the

castle

and the bridge attached to the curtain wall tower are weakened and

largely putrefied. Also the 4 panes of the 2 interior gates

are

completely defective and the walls behind the said doors and are in a

large part taken to decay. And the planking of the 4 turrets

at

the top of the keep are almost rotten and defective. Also the

curtain wall surrounding the tower is prostrate in many places and the

remainder threatens to ruin and the outer door of the tower is wanting

strength. The battlements and wallwalk of the walls of the

castle

towards the town have deteriorated in many places and need great

repairs. One of the turrets in the curtain walls of the

castle

has quite rotted away. Also the battlements and wallwalk of

the

external barbican are in many places prostrate and require great

repairs. Also the small door (postern?) of the barbican is

weak. Truly

in the said castle is a complete lack of crossbows and all manner of

arms necessary for the munitioning of the fortress.

This list proves pretty much that the castle was standing much as it is

today, but already much in ruin. On hearing the report orders

were issued to the sheriff to ‘amend and repair the bridges

and

buildings of Scarborough castle where absolutely necessary against the

coming winter'. This hardly sounds sufficient to renovate the

crumbling fortress. Later again on 1 August 1260, the sheriff

was ordered ‘to repair without delay where

absolutely

necessary

the recent breaches in Scarborough castle spending up to £12,

unless it could be done for less'. Again this hardly suggests

that any serious repairs were undertaken.

The war cast its shadow over Scarborough again on 10 July 1264, when

the prisoner king ordered Subconstable John Oketon of Scarborough

castle to deliver the fortress to Henry Hastings. However, if

he

refused this command and insisted on only relinquishing his charge to

the king in person, he had a safe conduct until 1 August to come and do

so. If he failed to do either ‘the king will betake

himself

grievously to his body, lands and goods'. John obviously

ignored

the threat and on 6 September 1264 the hostage king again directed

letters committing Scarborough castle, ‘by the counsel of the

barons', to John Eyvill (d.1291), ordering Subconstable John

‘the

knights and others in the garrison thereof, as they have not delivered

the said castle to Henry Hastings... as the king had commanded, at

which the king is amazed, that... they deliver it to John [Eyvill] by

chirograph with the armour, victuals and other things found

within'. Surprisingly John Oketon seems to have obeyed the

barons

as it was recorded that during the recent disturbances, Walter Bulkton,

the steward of Gilbert Gant (d.1274), was in rebellion against the

Crown, first with Baldwin Wake (d.1282) at Richmond and then with John

Eyvill (d.1291) in Scarborough castle. Regardless of this,

John

Oketon was back as constable of the fortress on 4 May 1266, when he was

ordered to hand the fortress over to the royalist, William Latimer

(d.1268). Possibly Eyvill had obtained the fortress soon

after 3

December 1264, when the baronial government issued a simple protection

for 49 men who were in the garrison of Scarborough castle.

This

was to last until Easter 1265. Presumably John Oketon, who

was

not named although his son and another Oketon were, made up the

fiftieth member of the garrison that had surrendered around this date.

With Scarborough castle in baronial hands, the king announced on 17

March 1265, that as the disputes between himself and his barons were

now at an end he was committing the castles of Dover, Scarborough,

Bamburgh, Nottingham and Corfe to the control of Prince Edward (d.1307)

for 5 years for the peace and tranquillity of the realm. As

Edward escaped from captivity on 28 May 1265, it seems likely that

little came of this. Certainly the castle was back in royal

control by the early months of 1266 and presumably from soon after the

battle of Evesham on 6 August 1265.

King Edward I (1272-1307) met with his council at the castle in 1275,

although on 27 March 1278, a view of the castle made when John Wesey

took over the custody of the castle from William Percy, found that the

cost of repairs would come to some £2,200. The

problems

found were very familiar - the main wooden bridge between the barbican

and the castle gate was so rotten that no cart could cross it, while

the bridge across the ditch to the inner bailey had entirely

collapsed. The main curtain was so decrepit that it could not

be

manned while 200 perches (3,300') of wall round the headland from the

gate to the chapel had fallen down. Quite clearly this would

have

included all the walls of the castle from the main gate to the northern

apex of the site and then back to the south, skirting beyond the chapel

of Our Lady built on the old Roman castle and then back around to the

site of the Cockfield Tower at the southern end of the main curtain

wall. Currently this entire perimeter is only about 2,200'

which

suggests a lot of the castle rock has disappeared into the

sea.

Finally it was recorded that the roofs of the great hall and the

queen's great chamber were in a rotten state, while the other buildings

were in urgent need of repair. This would suggest that

nothing of

note had been done to the castle since the weak efforts of the mid

thirteenth century. Once again there is no evidence that such

an

immense sum was ever expended on the castle. King Edward was

again at Scarborough on 27 September 1280, while Welsh and Scottish

prisoners were sent here in 1295 and 1311.

In 1308 the right to live in the castle was granted to Lord Percy and

his wife, so over the next 40 years they and their descendants

proceeded to build a bakehouse, brewhouse and kitchen in the inner

bailey, although the rest of the fortress was generally only repaired

when in extreme need. Regardless of this, some royal repairs

were

carried out at Scarborough castle. As early as 9 January

1312,

John Rolleston and Talifer Tilly were ordered to spend up to

£40

on repairing the king's houses in Scarborough castle. Around

Christmas 1311 Piers Gaveston had returned from exile and spent his

time in the North. By March Piers seems to have taken a hand

in

the refortification of Scarborough. His return had stoked

baronial discontent and on 4 May 1312 Gaveston and Edward II were

surprised by baronial forces at Newcastle on Tyne, the pair then fled

to Tynemouth and took ship to Scarborough, Gaveston remaining there

while the king moved to York to raise troops. At this point

Gaveston was besieged within Scarborough by Pembroke, Warenne, Henry

Percy and Robert Clifford. On 17 May the king ordered the

barons

and all their men in arms to raise the siege. However, on 19

May,

Piers decided to surrender the poorly provisioned, and judging from

later reports semi-ruined, Scarborough castle and allow himself to be

taken to York to negotiate a settlement with the king. If

such a

settlement was not forthcoming by 1 August 1312, Piers would be allowed

to return to Scarborough. Despite this agreement, instead of

the

proposed negotiation, Piers found himself waylaid and executed near

Warwick on 19 June 1312.

After Piers' death, work continued at Scarborough castle and on 27 June

1312, orders were given for timber to be carried to the fortress for

its repair by the keeper, Chaplain John Rollestone. It was

also

noted on 2 September 1312, that the town defences had been seriously

impinged upon. Some time back Thomas Uttred the Elder had

demolished 100' of the town wall and built a house that long on the

site, while William Nessingwyke owned a house similarly built over the

site of another 30' of the wall. Further encroachments had

been

made upon the town wall and the castle moat. On 24 October

1313,

it was noted that divers workmen had been working in Scarborough castle

since 1311/12. Other works were recorded as carried out at

the

castle between 8 July 1311 and 7 July 1316. These works,

however,

do not seem to have been warlike in the early stages, with an order to

provide timber to repair the chaplain's houses and other necessities

for the munition of the castle being issued on 9 March 1314.

The

same day the king complained that his men and servants bringing timber

to repair the castle had been set upon by certain persons who forcibly

took the timber from their ships and assaulted them. The work

may

have been finished by 6 March 1315, when allowance was made to John

Rolleston and Talifer Tilly for £94 spent during July 1312 to

July

1313, for the pay of workmen lately working on Scarborough

castle. They were also to receive a further £3 14s

6d which

they say

they have paid over and above the allocated £94.

Finally some work on the castle defences were undertaken and between 8

July 1318 and 7 July 1320, the castle constable stated that the

gatehouse windows, keep with its lead turret and chapel, the Queen's

Chamber (camera regine),

Cockfield Tower and the great bridge had been repaired. These

works had included the Queen's Chamber being virtually rebuilt, with a

porch with a stone foundation being added to it. Also repairs

had

been made to an old hall (vetus

aula), a middle hall (media

aula) and the hall in the courtyard (aula in curia).

Obviously these terms could be applied to a variety of

places.

There was certainly a hall in the keep, another may have stood in the

southern corner of the inner ward, while the free standing building now

claimed as the king's hall could have been the hall in the

courtyard. Quite obviously it is unprofitable to make any

plausible identification. Adjoining the chamber to the north

was

the Queen's Tower, though whether this was the attached tower or that

30' along the curtain is a moot point. This

marked the end of a period of considerable refurbishment, it being

noted on 6 March 1335, that 163 oaks had been cut down from Pickering

forest by the order of Edward II (1307-27) and used to repair the

defects in Scarborough castle.

On 2 September 1330 an inquisition on the state of the castle recorded

the deteriorations that had occurred in the times of Henry Percy

(d.1314) and his predecessors, Ralph Fitz William, John Sampson,

Talifer Tilly, John Mowbray (d.1322) and Giles Beauchamp

(d.1361). Repairs needed included the great drawbridge

between

the barbican and the castle, a wall in the castle by ‘le

Wylehole', the castle rock on the north face of the castle which had

been broken by the sea, the iron bars on the windows of the great hall

within the keep, the Cockfield Tower and the 10 turrets of the great

wall. Repairs were also needed to velvet trappings, white and

coloured haketons, a cotarium barrez with allett, cuisses of red

cendal, velvet and plate with pulley pieces, shin armour (schynbandes),

jambers, a hauberk, habergeons, corsets, collarets, shoes, gauntlets of

mail and of plate, coifs, helmets with visors, basinets, plates, pieces

of iron shaped for schynebandes, crossbows, quarrels, garroks tipped

with iron, great engines and springalds. Then, on 14 October

1330,

it was noted that Giles Beauchamp (d.1361) had received 40m

(£26

13s 4d) for himself and 6 men at arms forming a garrison at Scarborough

castle when he was custodian. Similarly on 22 March 1331, the

king ordered the keeper of the castle, Henry Percy (d.1352), to

supervise the repair of the houses, walls, turrets and bridges of

Scarborough castle spending up to 100m (£66 13s 4d) on the

job. The order had to be repeated on 25 May 1331 as the

command

had not been acted upon.

Despite all this work under Edward II, the castle had

continued to

decay and in the early 1330s it was recorded that part of the castle

rock had been carried away by the sea in the time of constable John

Mowbray in 1317. This collapse had taken a section of curtain

wall with it. It was also alleged that the reason for this

loss

was that the king refused to send money for the castle's

upkeep.

Such a statement seems disingenuous, as not even Canute could have kept

the sea at bay from this windswept fortress. Despite the

apparent

loss of all the coast side of the castle's defences, in 1337 some

£74 spent on rebuilding the great bridge in stone under the

auspices of Mason John Brumleye. With this all work seems to

have

ceased at Scarborough for the next 20 years. In 1342 another

survey found that in the time of Constable John Mowbray the great hall

and other parts of the castle had become so ruinous that they fell

down, the dilapidations during his tenure rising to

£200.

Two constable's previously, in the time of John Sampson, repairing the

defects would only have cost £100.

Work on Scarborough castle seems to have begun again in the

late

1350s. On 3 March 1361, an inquisition was made inquiring

into

the costs incurred by the repairs done by Richard Tempest at

Scarborough castle and the defects that remained after his

work.

This important document explains much of the layout of the fortress and

names several of the buildings within. It is therefore worth

quoting in full.

Two

wooden bridges, one called le

draftbridge being the common way into the castle were so

decrepit that

some trying to cross fell and others hardly escaped the

danger.

Seeing that otherwise no one could enter the castle, Richard repaired

them spending £10 on timber. A building

called le

Porterhouse by the outer gate was greatly damaged as to

the walls and

the timber decayed for want of roofing and it is necessary for the

keeping of the castle, so that it may be conveniently crossed, he

repaired it for 48s including purchase of timber and straw for

thatch. A tower beyond the inner gate called Constabletower

roofed with lead and a latrine adjoining roofed

with planks, were broken down and the roof damaged and gone; and as the

tower was specially ordained for the safety of the castle, he had the

leaden roof entirely taken off as it could not be mended otherwise and

repaired where necessary and replaced and the latrine roofed with new

planks, all at a cost of £10 including purchase of lead,

solder

and planks. The castle wall adjoining the gate on the west

side

was so eaten away by sea salt (salsuginem

maris) for a length of 60'

and a height of 16' that it fell into the sea and [the castle] was open

at that spot. Richard therefore built a new wall there of the

same length and height and 6' thick with jamb stones (shoulder stones)

bought in Scarborough town and other stones brought from a

distance. The wall on the south side of the inner gate was

eaten

away in a like manner for a length of 35' and a height of 12' and fell

into the castle becoming in its fall like fine sand; and as the castle

was laid open at that spot Richard rebuilt the wall of the same length

and height and 6' thick of new stones at the cost of

£10. A

stable in the castle was damaged and the timber decayed and, as it was

the greatest necessity because there was no other stable in the castle,

he rebuilt it entirely at a cost of 45s including purchase of timber

and straw for thatch. Qweneschambre with

stone walls and

a lead roof, newly built during the lordship of Lord Percy, was fallen

down, the roofs being much damaged; and seeing that if the king or

queen or any of their ministers had to dwell in the castle, they would

have no dwelling place but their chambers, he had them made anew and

strengthened with timber where it had decayed, the defects of the roofs

mended where most needful, new doors and windows made and the defects

in the walls of the great chamber mended all at a cost of £10.

A kitchen called Kyngeskychyn with a

small

larder attached, served both a hall called Kingeshalle which

formerly stood there and the great chamber called Qweneschambre.

The tiled roof had long been stripped off

so that the walls were decayed and threatened to fall. As it

could not be well dispensed with, because there was no other kitchen in

the castle except for in the great tower, he repaired the walls and

timbers at a cost of £6 including the purchase of timber,

tiles

and lime. A turret on the south wall of the castle facing the

town was eaten away by the sea salt and flung down by the force of the

wind into the castle ditch (pit - foveam)

and as the castle was open at

that spot, he rebuilt the turret, partly with the fallen stones and

partly with new stones bought from a distance at a cost of £9

6s

8d. The above are the only expenses incurred by him in

repairing

the walls and buildings of the castle.

A barbican before the outer gates, a

postern, the

barriers before the gates, a tower in which these gates are, a place

called the Turnpike by the tower and the walls on each side of the

entrance from the outer gates to the tower called Consabletour

in which the inner gates are, except a part new built when Lord Percy

was keeper, are eaten away by the sea salt and threaten a grievous

collapse; and a wall under the Draghtbrigg is

cracked from top

to bottom. Unless the tower and the walls are speedily

repaired

they cannot be saved from ruin; the towers, barbican and walls cannot

be repaired for less than £200.

The wall of the castle on the south side

towards the

town from the Constabletour

to a place and tower called Ledentour,

except a part rebuilt by Richard Tempest as above and [the towers]

built and covered with lead as the jurors suppose, between the 2 towers

named are eaten away by sea salt and shattered and greatly damaged so

as to threaten a dangerous collapse. The battlements of the

towers, the wall, the wallwalk (basis)

on which there was a common

passage on the top of the wall and towers and the stone steps lately

arranged to go up thereto, have quite fallen down. The leaden

roofing of the 4 towers and the timber thereof has either been carried

away or decayed, but at what time the jurors know not, as they cannot

remember seeing the towers with their roofs on. The repair of

the

wall and towers, the renewal of the battlements and the replacement of

the leaden roofing on new timber could not be done for less than

£233 6s 8d.

The castle wall on the south side

towards the town,

from the Ledentour to the tower called Cokfeldestour at

the end

of the wall on the edge of the sea, is eaten away by the sea salt and

very ruinous; and the 2 towers and the 5 towers between them, whereof

the large 3 were roofed with lead, but not the smaller, as the jurors

suppose, are broke down in like manner, except where rebuilt by Richard

Tempest and much damaged as to the leaden roofing and the timber, both

of the upper portion lately arranged to support the leaden roofs and of

the joists and the flooring of the chambers, so decayed as to be of no

use for repairs.

The leaden roofing of the chamber called

Qweneschambre

which abuts on the wall between Cokefeldtour

and

Ledentour

and was repaired by Richard Tempest, is damaged in places and

as it is much more needed than the other towers, it should be sooner

repaired. These roofs cannot be sufficiently repaired unless

the

lead is completely stripped off and melted into new sheets together

with a quantity of fresh lead and the upper framework of the towers and

the floors of the chambers that were in them cannot be repaired except

by complete rebuilding and the same with the stone and wooden steps to

go up the wall and towers and [also] the stone wallwalk along the

top. The whole of the defects in the wall, towers and

chambers

aforesaid cannot be repaired for less than 1,000m (£666 13s

4d)

including the cost of timber and lead. A tiled building

called Noricehous

annexed to the Qweneschaumbre

with a fireplace of

wood, tiles and plaster and plaster walls is quite broken down and the

timber so [decayed] for lack of roofing as to be useless for repairs,

so that it must be completely rebuilt. One of the 3 chambers

attached to the Qweneschaumbre

with a tiled roof and lime-whited clay

walls is so damaged that parts of the roof and walls have fallen down

and the timber is decayed for lack of roofing; the damage can be

repaired for 40s.

The wall enclosing the castle on the

west side

beginning from that built by Richard Tempest by the Constabletour and

extending along the sea on the north side to a place called Tristones at the

north corner of the castle is ruined both by

the corrosion of the sea salt and the cracking of the rock whereon it

is built, so that the foundations are much broken and it leans

outwards. The stone [steps] lately arranged to mount the wall

and

the stone wallwalk along it have completely fallen down and cannot be

repaired unless the wall is completely rebuilt except for some very

short sections which cannot be done for 500m (£333 6s

8d).

The wall enclosing the castle on the east side from the north corner

called Tristones

to Co[kefeldtour] at the corner towards the south,

built and supported for much of its length on a cliff on the sea-face,

is eaten away and broken down by the sea salt, together with part of

the cliff and has fallen into the sea; it can only be repaired by

complete rebuilding which cannot be done for less than £1,000.

A wall under the great tower, built

across from the

west wall of the castle to the barbican round the said tower, has in it

a third gate of the castle, through which is a common way of

entry. A tower over this gate is said never to have been

roofed. This wall is damaged in places, the battlements of

the

tower fallen, the wooden gates lately arranged to close the gateway

broken and their timbers and iron binding decayed. The

repairs of

the wall and rebuilding of the tower and the making of new wooden gates

will amount to not less than £40.

The leaden roofing of the great tower,

the 3 corner

turrets thereon and the chapel attached thereto is damaged and broken

in places, and a corner turret in which there is a building

called Waytehous

is completely destroyed; the timber of the upper

framework of the chapel and of the joists, floors etc is decayed for

want of roofing; the walls of the keep and chapel are beginning to be

damaged, both for want of repairs to the roof and because one of the

[corner] turrets is completely unroofed; the doors and windows in the

keep and chapel, of wood, bound with iron, and their ironwork,

including locks, [drawbar] slots and staples are damaged by rust and

wind. The [keep and] chapel cannot be repaired unless the

leaden

roof is completely stripped off, the upper framework of the chapel

[repaired] with new timber and the lead melted, together with fresh

lead, to form a new roof. The defects in the keep and chapel

cannot be repaired for less than 100m (£66 13s 4d) including

the

purchase of timber, lead and ironwork. A wall called the

barbican

of the keep [inner ward] built all around it is much damaged and broken

in its foundations, so that most of it has fallen and the part still

standing threatens to fall; it can only be repaired by rebuilding which

cannot be done for less than £300.

When Lord Percy was keeper 2 thatched

buildings were

put up within the barbican [inner ward] for a kitchen, bakehouse and

brewhouse, which have now fallen down and the timber is so decayed as

to be of no use for rebuilding. They can only be repaired by

rebuilding which cannot be done for less than £20.

A hall

called Kyngeshalle

said to have been roofed with tiles, used to

stand by the Qweneschambre,

but has long been entirely in ruins except

that parts of the wall are still standing and the timber is so

destroyed that nothing remains; it can only be repaired by complete

rebuilding which would cost £40. Total spent on

repairs by

Richard Tempest, £79 19s.

In total this meant that Constable Richard Tempest had spent a recorded

£59 19s 8d on the castle (not the £79 19s claimed)

and that

a further £2,902 needed to be spent to bring the fortress up

to

scratch. After this inquiry Constable Tempest was ordered on

28

February 1363, to cause the defects of houses, walls, and other

enclosure of Scarborough castle which are in need of repair to be

repaired.... As a result of this, before 1376, Richard had

spent

some £165 remedying some of these defects. These

repairs

were obviously not on a scale to cover the nearly £3,000

needed

to remedy all the reported problems. Even so, by 1393, the

estimated cost of these repairs had dropped to £2,000 after

the

prior of Bridlington and the bailiffs of Scarborough had been asked on

6 February 1393 ‘to examine the condition of the castle and

enquire into all defects both as to walls, gates, turrets, loops,

garrets, bridges, barriers, dykes, mills and other buildings and as to

the equipment of armour, artillery, victuals etc'. The

previous

day, 5 Feb 1393, John Mosdale had been made keeper of Scarborough

castle, a post forfeited by John St Quentin (constable from 1382), to

receive as wages all

issues and profits belonging to the castle together with a further

grant of 50m (£33 6s 8d) a year on condition that he spent

40m

(£26 13s 4d) yearly on castle repairs. Yet it was

only 3

years later on 12 May 1396 that Mosdale was ordered to set masons,

carpenters and other workmen to repair Scarborough and Newcastle on

Tyne castles. The order was repeated under Henry IV

(1399-1412)

on 5 May 1400. These works were still progressing on 25

December

1401 when Mosdale was granted an extra 10m (£6 13s 4d) yearly

‘for his allowances for the repairs of the [Scarborough]

castle

and long has been and still is keeper of the king's castle of Newcastle

on Tyne without fee or reward'.

This state of affairs, with the constables maintaining the castle,

proceeded for decades, with the king finally asking the sheriff of

York, on 24 July 1410, if John Mosdale, who had received 50m

(£33

6s 8d) pa from 1393 to the present day, had actually spent that money

properly, ‘or converted the same to his own use'?

Whether

John had cheated or not is unknown as King Henry IV (1399-1413) ordered

the proceedings halted. However Mosdale was allowed to remain

as

constable and was even, on 4

June 1412, given another royal commission. During his 30 year

tenure of this office (1393-1423), he may have carried out many repairs

of the fortress with the £800 allocated to him for this

purpose

during that time. Indeed, if the subsequent constables who

are

known to have held this office on the same terms until at least 22

December 1459, also were honest, some £1,813 6s 8d would

have been spent on the castle upkeep between 1393 and 1461.

During his term of office, some of the money seems to have been spent

on building Mosdale's Hall into the site of the Queen's

Chamber.

On 15 July 1423, Thomas Burgh was granted the castle on similar terms

to Mosdale on the latter's surrender of the boon. It was also

noted at the time that the issues and profits of the castle were worth

£20 a year. During Burgh's term of office (1424-29)

the

Constable's Tower was taken down and rebuilt as it was on the point of

falling. Thomas Hyndeley, master mason at Durham Cathedral,

was

sent for ‘to devise and ordain the most siker ground of the

Constable Tower'. This tower was plainly the inner gatetower,

isolated from barbican and castle by the 2 drawbridges. At

the

same time a new section of wall was made between the Watchhouse

(wacchehous

- probably now the solid turret at the top of the second

ward south curtain) and the castle bridge. Subsequent

constables

held the castle on the same terms as Mosdale, the last grant being made

being to Earl Henry Percy on 22 December 1459. He was killed

at

the battle of Towton, just over a year later on 29 Mar 1461.

Scarborough castle was last used as a royal base in 1484 when Richard

III (1483-85) prepared a fleet in the bay below to oppose hostile

landings.

When Leland passed in the 1530s he found:

At

the east end of the town, on the one point of the

bosom of the sea, where the harbour is, stands an exceeding goodly

large and strong castle on a steep rock, having but one way by the

steep slaty crag to come to it. And or ever a man can enter

the

area of the castle there are 2 towers and betwixt each of them a

drawbridge, having steep rocks on each side of them. In the

first

court is the arx and 3 towers in a row and then yoinith a wall to them,

as an arm down from the first court to the point of the sea cliff,

containing in it 6 towers whereof the second is square and full of

lodgings and is called the Queen's Tower or Lodging.

Without the first area is a great green, containing

(to reckon down to the very shore) sixteen acres and in it is a chapel

and beside old walls of houses of office that stood there.

But of

all the castle the arx is the oldest and strongest part. The

entry of the castle betwixt the drawbridges is such, that with costs

the sea might come round about the castle, the which stands as a little

foreland or point between 2 bays.

Around the same time as this in 1537, it was reported that the castle

constable, Sir Ralph Eure, had, on assuming the constableship from Sir

Walter Griffith, stripped the lead off the tower and turret roofs, sent

some to France in exchange for wine and made the rest into a brewing

vessel. Further, on 7 January 1538, it was reported that a

part

of the wall with the ground under it had ‘shot down in the

outer

ward between the gatehouse and the castle'. Presumably this

marked the collapse of the western approach wall from the main

gatehouse beyond the barbican to the keep.

Nearly 3 months later on 25 March 1538, a view was taken of Scarborough

castle by Sir Marmaduke Constable and Sir Rauff Ellerker Junior. This

found that the barbican, or as they called it, ‘the outer

ward is

in circuit 98 yds (294'), of which 37 yds (111') are clean fallen

down'. The figures given for this show that by this they

meant

the circuit of the barbican which is about 300', the outer ward being

over 1,000 long and not being a circuit, unlike the barbican.

The

111' which had fallen was obviously the rear, north side of the

defence. Beyond this was the approach, described as

‘a

second ward of 154 yds (462'), of which 38 yds (114') are fallen down,

with 2 bridges and turrets'. The gatehouse was described as

‘within the same (bridge) a turret in length 9 yds (27), in

height 13 yds (39'), in breadth 5 yds (15'). It's defences

also

included a portcullis, although all traces of this are now

gone.

Above the second ward was a small, otherwise unmentioned

‘third

ward'. This was entered ‘neither by a tower nor a

house,

but by a pair of evil timber gates 13' high and 10' broad with a place

for

a portcullis'. The ward was ‘square like a court,

22 yds

(66'), all in good repair, except the gates'. This is

obviously

the area between the keep and the Master Gunner's House, which house as

yet did not exist. Beyond this was ‘the inner or

fourth

ward' which was ‘156 yds (468') in circuit, with three

turrets'.

If the dimensions quoted are correct, they did not include the great

keep as part of the defences of the inner ward, for this and its

associated buildings would have added another 120' to the

distance. The core of the defences were then described,

‘the

dongeon or high tower of 4 stories with 5 turrets' and was 18 yards

(54') square. It would therefore appear that originally the

keep

had 4 corner turrets and presumably a fifth that contained the

forebuilding with chapel. Within the keep were ‘the

ordnance concepts of a great brazen gun, an old serpentine, four bases,

and eight chanters; but no shot or powder'.

From the inner ward there was ‘a straight [wall] that

stretches

to the sea-side towards the south-east, 207 yds (621'), and round

towers, 2 storeys high and 18' in diameter called Queen's Tower,

Bosdale Hall, Cokhyll Tower, as well as 2 others'.

Interestingly

this is the first measurement that certainly does not tally with

reality, the

real wall from the inner ward being at least 720' to the

inner ward junction from the Cockhill

or

rather Cockfield Tower. This latter has now fallen with that

part of the

headland into the sea. Also Bosdale is obviously the Mosdale

Hall

and the last before the Cockfield Tower of the outer ward had already

collapsed. Finally, of

the castle defences, it was noted that the north wall along the

headland ran for ‘140 rods (2,310'), on the sea

cliff'.

Such a distance is almost exactly the current distance around the

periphery of the castle rock - from the Master Gunner's House, round

the

back of the Roman castle and to the site of the Cockfield

Tower.

Quite clearly from this, the headland was fully fortified in 1538, even

if the wall was not in a good state of repair, it being clearly stated

that

‘there are 3 places where men may climb it, which may be

mended

for 40s'. Within this defence ‘the castle garth is

480 yds

(1,440') by 240 yds (720') [and] within it is a pretty chapel of Our

Lady and a fair well, but no bakehouse, brewhouse, nor

horsemill'. It was then estimated that the materials required

to

repair the castle would be 2,102 tons stone, 337 tons timber,

9½

tons iron and 40 foder of lead. Usefully the survey concluded

with stating that ‘stone can be had at Haburne wike, 6 miles

off;

rough stone and lime from the sea cliff; timber at Rayncliff, within 3

miles, and slate at Sawdon More, within 5 miles'.

Although it remained a royal fortress until 1619 there seems to have

been little effort made with its upkeep. The end for the

castle

came during the Civil War of 1642-51 when it was twice

besieged.

The Parliamentarian governor, Hugh Cholmley, became disillusioned and

switched to the Royalist cause after 5 months in occupation of the

castle. The castle was then seized by his brother for

Parliament,

but Cholmley persuaded him to surrender the fortress back to

him.

After the Royalist defeat at Marston Moor and the fall of York, John

Meldrum marched on Scarborough in August 1644. In January

1645

the siege began in earnest, with the town only being overrun on 18

February. A high point of the siege was when Meldrum fell off

the

cliff and plunged 200' while apparently chasing his hat on a blowy

day. Surprisingly he recovered and resumed his siege in