Bamburgh

Bamburgh is a most important site in the history of Britain.

Sadly the castle is only beginning to receive proper archaeological

excavation. The site of Bamburgh castle was fortified from an

early date, even if it still is in use today and this fact of some 2

millennium of continuous usage has much disguised the early phases of

the castle. Limited excavation has shown that the rock was

occupied continuously from the first century BC until the

Renaissance. After the arrival of the Romans it is thought the

site may have been used for a beacon. Later Bamburgh appears to

have been the royal centre, Din Guyardi.

As such it was ‘the capital' of the royal dynasty of

Northumberland which produced the religious hero, St Oswald

(d.642). His remains were said to have been preserved in the

basilica of St Peter which stood upon the high point of Bamburgh

rock. According to much later reports the history of the site

began in 547AD when King Ida of Northumbria during his 12 year reign:

built Bambrught, which was first enclosed with a fence and afterwards a wall...

The Winchester chronicle which mentions this is the earliest of the

renditions of the Anglo Saxon Chronicles and probably dates to around

890. The implication from this is that by the tenth century

Bamburgh was seen as an ancient stone fortress that dated back

generations. Ida seems to have died in 559 or 560 and knowledge

of Bamburgh disappears with him for some 200 years, although a little

after 1116 it was recorded that King Oswald's hands were preserved

undecayed in Bamburgh in 641. Simeon Durham (d.1129+) states that

these were held in a case within the church standing in Bamburgh

castle. He also stated that the castle was named after Queen

Bebbab who was supposed to have been the wife of King Æthelfrith

of Bernicia (d.616). According to Bede, King Penda (d.655) twice

unsuccessfully besieged Bamburgh, on one occasion trying to set fire to

the town within the wall by setting a great fire at the base of the

castle rock.

In 750 it was recorded that Bishop Ealdwulf (Eadberto)

of Lindsey was captured by King Ceolwulf (d.764) and held captive in

Bamburgh, presumably after the king had besieged the basilica of St

Peter at Lindisfarne. In 774 Bamburgh was described as being:

The well fortified city of

Bebba, not very large, occupying the space of 2 or 3 fields, having one

excavated entrance which was only reached by wonderfully lofty

steps. On the summit of the hill is a splendidly made church in

which is a beautiful cabinet. Within this lies the unspoiled

right hand of King Oswald, as Bede the historian of this nation tells

us. There is to the west, at the top of the city, a wonderfully

excavated well sweet to drink and pure to see.

In 926, King Aethelstan (924-39) expelled Aldred Fitz Eadulf from Bebbanbirig city, while in 993 the army of the Danes broke into Babbanburh

and carried away with them all that was found within. The castle

was presumably otherwise undamaged and soon reoccupied as it was

obviously still functional in 999 when Earl Waltheof of Northumbria

(d.1006+) defied King Malcolm MacKenneth (995-1034) from behind its

walls.

The castle seems to have survived intact from the sixth century right

up to the time of the Norman Conquest. Probably in the 1050s the

church seems to have been semi derelict when a monk from Peterborough

abbey succeeded in stealing the arm of Oswald from its care. Of

this Reginald of Durham remarked:

The city formerly renowned

for the magnificent splendour of her high estate, has in these latter

days been burdened with tribute and reduced to the condition of a

slave. She who was once the mistress of the cities of Britain has

exchanged the glories of her ancient Sabbaths for shame and

desolation. The crowds that flocked to her festivals are now

represented by a few herdsmen. The pleasures her dignity afforded

us are past and gone.

In the meantime, war came again to Bamburgh. The contemporary

Symeon Durham (d.1129+), who was born around 1070, stated that after King William I (1066-87) had laid waste the North of England during the latter part of 1070:

Earl Gospatric, who had been

made earl of Northumberland by King William, invaded Cumberland and

depopulated it. Having accomplished the slaughter and the

burning, he returned with great booty and shut himself up with his

allies in the most reliable fortification of Babbanburch, from which he often burst out, weakening the strength of the enemy, for Cumberland was at that time under the dominion of King Malcolm, not possessed by law, but subjugated by force.

Some 25 years later in 1095, the castle was obviously still defensible. During the reign of William Rufus

(1087-1100) a conspiracy was hatched against the king by Earl Robert

Mowbray of Northumberland, William Eu, Stephen Aumale, the king's

cousin, together with many others. However the plot was

frustrated by King William II forming the English army and besieging the rebels for 2 months in Newcastle at the mouth of the River Tyne. The Durham chronicler notes:

Then he [Rufus] stormed the

besieged castle and handed over the earl's brother, together with the

knights who he found there, to custody. After this he established

a castle before Bamburgh, that is, the city of Queen Bebba, into which

the earl had fled, and named it Bad Neighbour (Malveisin); and after placing soldiers therein, he returned to the south of the River Humber (Suthymbri). After his departure, the guards of Newcastle

promised Earl Robert that they would permit him to enter, if he should

come in secret. So he, having become joyful, went out one night

with 30 soldiers to accomplish this. When this was discovered,

the knights who guarded the [siege] castle pursued him, communicating

his departure by messengers to the keepers of Newcastle.

Which he [Robert], being unaware of, attempted to accomplish what he

had begun on a Sunday. But he could not do this, for he had been

caught.

For this reason he fled to the monastery of St. Oswin, king and martyr [Tynemouth].

Were, on the sixth day of his siege, he was severely wounded in the leg

while he was resisting his adversaries, many of whom were killed and

wounded. Of his own men some were wounded, but all were taken

prisoner; but he fled into the church; from which he was extracted and

placed into custody.

This succinctly sums up the events of Spring of 1095. Robert

Mowbray was the third and rather more successful Norman earl of

Northumberland. However, like his predecessors, he felt his

distance from London gave him an independence from the rest of the

Norman kingdom. As such he plotted with other nobles to place

Stephen Aumale (d.1135) on the throne in place of Rufus.

The king seemed aware of these plots and demanded that Robert come to

court to answer a charge of piracy after Robert and his nephew Morel of

Alnwick fame, had violently plundered 4

canard trading vessels from Norway. The earl's refusal was taken

as an act of rebellion, which allowed Rufus to act first against the

rebels before they were ready. The king rapidly marched on Newcastle

where the earl's brother underwent a 2 month siege, while Earl Robert

attempted to breath life into the rebellion. However, on the fall

of Newcastle, Robert was forced back with

his wife, Matilda and Sheriff Morel of Northumberland, on Bamburgh

castle. The king found the fortress too strongly defended to

storm so he built a castle to control Northumberland and

Bamburgh. It has been argued that this was a siege castle due to

much later accounts of the siege. However, such suggestions have

always floundered on the fact that there are no visible castle remains

within eyeshot of Bamburgh castle which would suit the designation

siege castle. It is therefore possible that the castle

‘before' Bamburgh was before in so far as it was between Newcastle

and Bamburgh, therefore coming after leaving Newcastle, but before

reaching Bamburgh. In this case it is worth suggesting that Rufus

used his large army to build a new fortress at Warkworth,

which was 20 miles away as his castle ‘before' Bamburgh.

These thoughts will be amplified more after looking at other accounts

of the war of 1095.

Another contemporary, Florence Worcester (d.1118), knew pretty much the

same story as Symeon, although he also noted the storming of another

fortress before Newcastle. Possibly this was Morpeth some 30 miles south of Bamburgh and 14 miles north of Newcastle straight up the Roman road. Florence wrote:

the king... assembled his

army from all England and besieged the castle of Earl Robert [Mowbray

of Northumberland], which was situated near the mouth of the River Tyne

[Newcastle], for 2 months; and meanwhile having stormed a certain fortress [Morpeth],

he made prisoners of nearly all the best soldiers of the earl and put

them in confinement. Then he took the besieged castle [Newcastle]

and placed into safe custody the brother of the earl and the knights

whom he found within. After this he raised a castle before

Bamburgh... into which the earl had fled and this he called Malveisin and having garrisoned it, he returned to the south of the Humber. After his departure, the watchmen at Newcastle

promised Earl Robert that they would allow him to enter if he would

come secretly. And he joyfully acceded and went out by night to

accomplish this with 30 knights. This becoming known, the knights

who kept the castle [Malveisin] followed him and sent messengers to the guards of Newcastle

to inform them of his departure; [Robert] being ignorant of this, on

Sunday he made his attempt, which failed, for he was detected.

Wherefore he fled to the monastery of St Oswin, king and martyr [Tynemouth],

where, on the sixth day of the siege, he was severely wounded in the

leg... while resisting the enemy many of whom were killed and

wounded... he himself taking refuge in a church from which he was

brought forth and placed in confinement.

The monks of Peterborough compiled a new Anglo-Saxon chronicle for

their house around 1121 after they had lost most of their possessions

in a great fire during 1116. This recorded that after Pentecost

1095 the king went against the earl of Northumberland:

and immediately he came there he conquered many and well nigh all the best men of the earl's court inside one fortress (faestene, ie. Morpeth) and put them in captivity; and then besieged Newcastle (castel aet Tine muthan besaet)

until he conquered it and in there the earl's brother and all those who

were with him. Afterwards he travelled to Bamburgh and besieged

the earl in there. But then, when the king saw that he could not

conquer it, he ordered a castle to be made before Bamburgh (he makian aenne castel to foran Bebbaburgh) and called it in his language Malveisin,

that is in English ‘Evil neighbour' and set it strongly with his

men and afterwards went southward. Then immediately the king had

gone south, the earl travelled out one night from Bamburgh towards Tynemouth (Tine muthan),

but those who were in the new castle became aware of it and went after

him and fought against him and wounded him and afterwards captured him

and of those who were with him, some they killed and some they took

alive.

Writing some 20-30 years after the event Orderic Vitalis (d.1142) stated:

They laid siege to the most

secure castle which is called Bamburgh. And since that

fortification was impregnable, because it seemed inaccessible on

account of the marshes and waters, and certain other obstacles across

the routes by which it was surrounded, the king built a new

fortification for the defence of the province and the confinement of

the enemy, and filled it with soldiers, arms and supplies. Those

who were part of the conspiracy [to kill the king] fearing detection

observed silence... The king... urged forward the works of the

new fortifications... while Robert, in deep tribulation, saw from his

battlements the works which were being carried on against him, called

loudly to his accomplices by name, publically recommending them to

adhere faithfully to their traitorous league to which they had

sworn...

After the king departed:

Robert Mowbray... attempting

to pass from one castle to another fell into the enemy's hands... and

lived 30 years in confinement....

At the present day, at any rate, waters and marshes do not constitute

the principal defences of Bamburgh, but the drainage where the town and

cricket field now stand might once have been more wet and certainly the

sea came right up to the rock under the barbican to the west at

Elmund's Well. Yet it is possible that Orderic was simply

guessing about the reasons for the strength of the castle upon Bamburgh

rock and invented the marshes. Regardless, it is quite clear from

these near contemporary accounts that there is no evidence as to what

form or even where this ‘siege castle' was built to control

Northumberland and keep Earl Robert bottled up. Warkworth

therefore still seems a good possibility, especially when there are no

traces of royal sized earthworks anywhere near Bamburgh. However,

Orderic's account, if it can be trusted, does seem to suggest that

Bamburgh and the siege castle were intervisible in 1095.

Roger Wendover (d.1235), writing many years later, is the first to describe the ‘siege castle' as a wooden fortress.

Since Earl Robert of Northumberland in his pride refused to go to the king's court [King William Rufus]

therefore advanced an army into Northumberland against Robert, where he

captured all the most powerful of the earl's household at Newcastle and bound them in chains; from there he proceeded to Tynemouth castle

in which he captured Earl Robert's brother and then on to Bamburgh

castle where he besieged Earl Robert; but when he saw that the castle

was impregnable, he built another wooden castle in front of that

castle, which he called Bad Neighbour (Malveisin), leaving a part of his army in it, he withdrew from thence.

And when one night the earl secretly withdrew from it [Bamburgh castle], the king's army followed him to Tynemouth; where, when he attempted to defend himself, he was captured without a wound, and imprisoned at Windsor.

Bamburgh castle was therefore surrendered to the king and all the

earl's supporters were badly treated; for William Eu was deprived of

his eyes and Earl Eudes of Champagne (Odo of Campania, d.1115+) and

many others disinherited.

The blunders of this history are manifold. Tynemouth was a priory and not a castle at this point in history. Earl Robert's brother was captured at Newcastle, not Tynemouth. Earl Robert's household was probably captured at Morpeth, not Newcaslte and he was wounded in the leg during his capture. How could the earl be defending Tynemouth which had already fallen to Rufus in Wendover's story? Finally, Wendover has it that Earl Robert was imprisoned at Windsor,

rather than being taken directly to Bamburgh to make the garrison to

surrender. Considering all of this and that no early source

mentions a wooden castle being built ‘in front of' Bamburgh, it

is possible that this ‘fact' too belongs to the realm of

Wendoverian fantasy.

One final possibility should be examined and that is that Orderic was

right in his history and that Earl Robert ‘saw from his

battlements the works which were being carried on against him' and

shouted to those in the newly rising defences. If this were the

case then it opens up the possibility that the siege castle was

actually built upon the Whinsill itself and that its ‘motte' lies

under the mid eighteenth century windmill. The mound of his lies

some 250' from the Smith Gate curtain and nearly 500' from the keep

battlements. Such would be well within shouting range.

Further, the 2 mottes surrounding Wigmore castle may

well date to the siege of 1155 and offer similarities in position and

style to the Bamburgh windmill mound. This said, there is no

reason why Malveisin could not have been the windmill mound at Bamburgh, while Rufus also built Warkworth castle to help control Northumberland.

At this time a probably genuine charter of Edgar, claiming to be king of Scots, was made to the bishop and monks of Durham. A supplement to this stated that it had been confirmed in the churchyard of Norham on 29 August 1095 ‘in the year in which King William the son of King William Senior,

built a new castle near Bamburgh against Earl Robert of

Northumberland'. This is often translated as the simple ‘at

Bamburgh'. However, the word used in the original is ‘apud'

which means at, by, near, among or before. Considering the

circumstances near or before seems a better translation. This

shows that an Anglo-Scottish army had reached as far as Norham, which they no doubt secured for Rufus, while Earl Robert was still resisting at Bamburgh.

According to Geoffrey Gaimar, who was writing before 1155, Earl Robert was penned up in Bamburgh when:

The king with his host went thither.

The new castle he then built.

Then he took Morpeth, a strong castle,

Which stood on a hill.

Above Wansbeck it stood.

William Morlay held it.

And when he [Rufus] had taken this castle

He advanced into the country.

At Bamburgh upon the sea

He made all his host stay.

Robert Mowbray was there...

According to Gaimar, Rufus pressed the siege hard and suffered many

assaults in return, but the castle began to run short of supplies, so

the earl fled by sea through the postern gate, having one man steering

the vessel which took Robert and a few folk to Tynemouth

where the king took him and imprisoned him. This is the only

account of Robert going by sea to Tynemouth and if the Windmill mound

was Rufus' siege castle, then it is doubtful if Robert could have got

past them to the port which seems to have been at Elmund's Well

postern. That said the idea of travelling by sea to Newcastle and Tynemouth might have been quicker by sea than by land as well as being more surreptitious.

With the revolt of 1095 over, Rufus took over Bamburgh as a royal castle. His brother and successor, Henry I (1100-35), made Eustace Fitz John of Alnwick constable of the castle. The vill was certainly in royal hands around 1119 when King Henry

granted the churches of St Oswald and St Aidan of Bamburgh to Nostell

priory. The first was probably in the castle and the second in

the town. That the vill and therefore the castle were still under

royal control is confirmed in the Spring of 1121, when King Henry informed the barons of Northumberland that he had given to Eustace Fitz John (d.1157) the land of the crossbowman (Arbaristarii)

which the king held in demesne at Bamburgh, viz the land of

Spindleston and the mill of Warnet [Waren Mill in Spindleston]

which used to render 60s annually, as well as the land of

Budle which used to render 40s; to be held as Eustace holds his

other lands from the king. This was witnessed by various local

dignitaries, namely, William Aubigny, Nigel Aubigny, Walter Espec [Helmsley], Robert Bruce [Lochmaben

and Skelton] and Forne [Fitz Sigulf]. The implication of all this

is that the castle remained a royal stronghold. The lands granted

to Eustace were probably those still held by William Vescy in 1168 and

worth 25s 4d. As a royal castle of Northumberland it was recorded

in September 1130, that Osbert the mason of Bamburgh had been allocated

35s directly from royal revenues and a further 7d for repairing the

castle gate. That Osbert was a mason would strongly suggest that

Bamburgh castle was a stone fortress needing maintenance. The

castle gate at this time was probably the Tower Gate, just north-east

of the keep, although Smith Gate might be meant.

Five years later King Henry I died and chaos came to his former domains. The story of the conquest of Northumberland by King David of Scotland (1124-53) is told under Alnwick castle, but events concerning Bamburgh will be recapped here. In early 1136, King David captured Alnwick castle. According to various chroniclers the Scottish king, cynically remembering his oath to King Henry I (d.1135), invaded the kingdom of England swiftly taking various garrisons in Cumberland and Northumberland and advancing on Durham,

while bypassing the royal castle of Bamburgh held by Eustace Fitz John

(d.1157), as this was too strong for him to assault. On hearing

of the fall of Carlisle and Newcastle, King Stephen marched north in the winter of 1136. He reached Durham where he made a treaty with King David. By this the Scottish king kept Carlisle and Cumberland, but restored Alnwick, Newcastle, Norham and Wark to English control.

Despite Eustace Fitz John's successful defence of Bamburgh in 1136, when his own castle of Alnwick

and the rest of Northumberland fell to the Scots, the king subsequently

moved against him, fearing treachery. In February 1138, King Stephen forced Eustace to ‘resign his fortress of Bamburgh into the king's hand'. Due to this:

Eustace Fitz John, one of the

great nobles of England, a good friend of the late King Henry as well

as a man of great prudence and a good councillor in secular affairs,

joined him [David] and was present in his army. King Henry had

committed a castle to him [Bamburgh] which he was compelled [by

Stephen] to return; being offended by this, in order that he might

avenge the injury that had been inflicted on him, he turned to his [the

king's] enemies.

The predictable result of stripping Eustace of his great charge, was

that at the first possible opportunity he joined the Scots and then

attacked Bamburgh castle, doing it great damage. The royalist Gesta Stephani thought that Eustace was an old and loyal friend of King Henry I

and therefore to gain justice and favour as it seemed to him and

several others like him, he took the opportunity of supporting the

Empress. Symeon Durham gave another take on the same story.

According to him King Stephen advanced during Lent to Wark castle before planning to continue to Roxburgh, where King David was preparing a night ambush for him. At this point King Stephen became aware of a plot within his army to turn him over to his Scottish enemies.

But the plot was made known

to King Stephen, who, preparing to return [south] in anger, forced

Eustace to resign the fortification of Bamburgh (Bahanburch) into his

own hands, and he hastily returned to England.

Whether the plot was real or imaginary did not really matter, for

Eustace lost control of Bamburgh which he had successfully defended

against King David in 1136. The actual events were thought so important some 150 years later that they were recorded for King Edward I on 20 May 1291. According to chronicles held at Carlisle cathedral:

In 1138 King David wasted and occupied almost all Northumbria and seized Carlisle, Newcastle and other towns excepting Bamburgh, when Stephen compelled him to return to his own land and followed him to Roxburgh...

In the autumn of 1138 King David again advanced over the border, this time marching on Yorkshire while he left 2 of his barons to besiege Wark castle. As he marched south Eustace Fitz John, ‘from whom King Stephen

had taken Bambrugh' abandoned his fealty to the English king and united

his forces to David's troops, rather than opposing them.

So they set out past

Bamburgh. There the young men of that same place, recklessly

boasting about the fortifications in the valley which they had built in

front of the castle, roused the Scots as they passed by. They

applied themselves at once to the destruction of the rampart, the

Scots' spirits excited, so they hastened inside and killed as many as

they caught.

Despite the success in taking the defences ‘in the valley', the

Scots and their ally failed to take Bamburgh castle itself. These

valley defences were quite possibly the barbican including Elmund's

Well. After the battle of the Standard on 22 August 1138, another

treaty was negotiated in April 1139 between David and Stephen.

This granted both Northumberland and Cumberland to Scottish control, although the castles of Newcastle

and Bamburgh were exempted. This exception obviously didn't last

long and by 1147 Bamburgh was in the hands of Earl Henry when he made a

charter to Tynemouth priory at Bamburgh exempting them from castle works on Newcastle or other fortresses in the earldom. With him at this time in Bamburgh were Bishop Ethelwald of Carlisle, Hugh Morville (d.1162), Earl Gospatrick of Dunbar

(d.1166), Gervase Ridel, Gilbert Umfraville, William Somerville

(d.1162) and Sheriff Ada. It is possible that the 5 fees in Earl

Henry's earldom of Huntingdon were granted to Eustace Fitz John

(d.1157) around this time and that they were related to his

constableship of Bamburgh castle.

King David's death in 1153 at Carlisle was followed a year later by that of King Stephen at Dover. At David's death Northumberland, presumably with Bamburgh castle, was turned over to David's younger grandson, William the Lion (d.1214). In England King Stephen's successor, Henry Fitz Empress

(d.1189), wished to turn the clock back to 1135 when his grandfather

died. He therefore required back from the Scottish king, David's

elder grandson, Malcolm IV (d.1165), the northern counties of England. Consequently in July 1157, King Malcolm surrendered to the king Cumberland and Northumberland with the castles of Carlisle, Bamburgh and Newcastle as well as the county of Lothian. This occurred when the 2 kings met at Peak castle.

Henceforward Northumberland appeared in the pipe rolls as a royal

county and in 1159 it was recorded that 60s 10d had been paid to John

Fitz Canute, the hereditary porter of Bamburgh castle. The clock

had been successfully turned back to 1135 in the North.

It seems likely that King Henry II

(1154-89) received a fully functional masonry castle in 1157, for

during the next 90 years next to nothing was spent on the

fortress. In 1164 the king authorised the spending of just

£4 on work on the keep. Later in 1168, 1170 and 1171 a

grand total of £112 3s 3d was spent on undefined castle works,

while in 1183, £19 6s 8d was spent on repairs to the castle and

its gate (porte). Considering the inner ward of Dover castle

including the great keep cost over £6,000 to build between 1180

and 1188, it can be seen that this sum, if this were all that was

spent, amounted to mere tinkering with the defences of Bamburgh

castle. By volume Bamburgh keep is 43% the size of Dover's

keep. As Dover keep,

admittedly the grandest of its type in England, cost over £3,000

to build, it would be expected that expenditure at Bamburgh would have

exceeded £1,000 if Henry II built this keep. By comparison the entire castle of Orford seems to have cost over £1,600 to build, although nothing was recorded as being spent there on the keep.

The pipe roll evidence considered above suggests that something large,

like a tower, was built at the castle during the period 1168 to

1171. Firstly £112 3s 3d would build quite a sizeable

structure, either a tower or a hall, while whatever was built was

finished in wood at a cost of £4 15s in 1171. This suggests

the structure took some 4 years to build. It is possible that the

building work was more extensive than the expenditure suggests as one

Crown tenant, William Fitz Waltheof, was fined 5m (£3 6s 8d) in

1170 for refusing to help in the works at the castle. Possibly

others gave their assistance for free and therefore these expenses were

not recorded in the pipe roll. After these works were apparently

completed, King William the Lion (1165-1214) in 1174 sent a force of knights from his siege camp at Wark

towards Bamburgh, but the sun having risen before they reached their

objective, they abandoned any attack. Nine years later repairs to

the castle and its gate cost £19 6s 8d.

In the next reign, King Richard I

(1189-99) spent just £3 1s 3d on amending the king's houses in

the castle during 1195 and 1197, while in 1198 just 10s was spent on

amending the castle gates. King John

(1199-1216) was rather more interested in the fortress spending

£110 13s 9d on repairs and amendments between 1200 and 1209, an

average of some £15 a year on the 7 years that repairs were

accounted for. On the first occasion £5 was noted as being

spent on repairing the houses within Bamburgh castle and a similar

amount on Newcastle. This is a similar amount to that apparently spent yearly on Carlisle castle.

Perhaps most northern castles usually had this sum nominally spent upon

them as the figure of £5 for amending the king's houses in

Bamburgh castle appears again in 1229. Against this, in 1202 it

was recorded that £3 12s 6d was spent on amending the king's

houses in Bamburgh and Newcastle

combined. The next year, 1203, amendments to whole fortress cost

a much more substantial £60 2s 5d. Similarly in 1204,

£12 was spent on repairing the castle while a further 17s 7d was

spent on amending the king's houses within it. The same year 3

crossbowmen were paid £24 16s 4d for staying in the castle for 36

weeks and 2 days at a rate of 7½d per day. In 1206, 26s

was split between amendments to the houses in Newcastle

and Bamburgh castles. In 1208 merely 25s 4d was spent upon the

same, but the next year 59s 8d was spent on repairing the king's houses

in Bamburgh alone. Quite obviously King John

was interested in keeping the accommodation within this fortress in

good condition and having troops within them. It should be noted

that virtually nothing was spent upon the actual defences after 1157,

unless this was done by expenditure outside that recorded in the pipe

rolls.

The castle history during the reigns of the first 3 Plantagenet kings seems quite peaceful, with King John

staying at the fortress between 13 and 15 February 1201. Around

1212 it was recorded that the office of porter of the main gate at

Bamburgh had been held by the descendants of a certain Canute since the

time of King William I (1066-1087). On 20 August 1212, Robert Fitz Roger (d.1214) of Warkworth was ordered to deliver the castles of Bamburgh and Newcastle

to Earl William Warenne (d.1240), Archdeacon Aimeric of Durham

(d.1217/18) and Philip Oldcoats (d.1221). The king stayed again

on 28 January 1213, while he was engaged in ravaging the lands of his

enemies in the North. In 1216 Philip Oldcoats seized a merchant

at Bamburgh, but was ordered on 23 August to release both him and his

ship.

Oldcoats was obviously still constable when he died early in 1221. As a result Hubert Burgh (d.1243) and the young King Henry III(1216-72)

came to Bamburgh castle with Brito the crossbowman and his 18

followers on 21 March. Hubert's first act there was to order the

sheriff of Northumberland to pay Constable John Wascelin, as well as

John Carpenter and Robert the porter, their proper salaries as well as

to build a grange, 150' long by 34' wide. The king also ordered

that Roger Hodesac should be reimbursed his expenses of 60s for

providing the castle with knights and serjeants on the death of Philip

Oldcoats and maintaining them until John Wascelin could take over as

constable. The minor amount of 10s 8d was then spent in building

a stone wall around the barn in the bailey, while the building of the

grange itself had cost £46 18s by 1222. During 1221 and

1222 Hubert Burgh had also authorised £5 to be spent on the

castle. Also, on 1 May 1221, the castle of Nafferton was ordered

to be demolished and the woodwork from it taken for the works at

Bamburgh castle. Further, the constable of Newcastle

was ordered to send 3 horn crossbows and 3 well strung wooden ones with

the crossbow of William Statton together with 4,000 quarrels to

Bamburgh. Soon afterwards the mounted crossbowmen Boniface and

Roger Quatremares arrived at the castle with a foot crossbowman, Roger

Bosco. These men were then paid for the next 8 years with the

mounted men receiving 7½d per day and the footman 3d.

Further work on the castle included repairing the turning bridge before

the great gate for £5 2s 2d. The only drawbridge certainly

at the castle was the one before the twin towered gatehouse at the new

eastern entrance to the castle.

In 1223 work was carried out on the floor planks (planchicii)

of the great tower of Bamburgh castle as well as on the keep guttering,

other turrets, the hall and other houses within the castle for

£14 13s 4d by the view of Adam Docsford and Nigel

Cordwainer. Carpentry was continuing at the castle during 1225

with their wages costing £10 8d. At this time the castle

seems to have had a fee of 100m (£66 13s 4d) per annum attached

to it to maintain the building and a garrison there. In 1226 this

went up to 120m (£80) and then in 1239 to 200m (£133 6s

8d). Repairs at the fortress were going on again on 28 November

1227, when Roger Hodesac, the king's serjeant of Bamburgh, was ordered

to let Constable John Wascelin have 106s in recompense for the money he

had spent having timber that belonged to the bishop of Durham brought

to the castle for its maintenance. The next year on 16 May 1228,

Serjeant Roger Hodesac was ordered to have the breach repaired in

Bamburgh castle and to have a carpenter do the king's works there at

fixed wages, namely 6m (£4) per year, the amount that his

predecessor used to receive. Three years later in 1231, £26 1s

11½d was spent on repairing the castle bridge, a stable within

the castle and work on a new chamber. In 1230, 1231 and 1238

£10 was recorded as shared with Newcastle on repairing the king's

houses within the castle. This was followed on 2 March 1233, by

the sheriff of Northumberland being ordered to have the castle gate

repaired without delay. The repairs were done by September 1234

when an account for works at the castle included £10 being spent

on amending the king's houses of Bamburgh and Newcastle

castles, £4 for the wages of John the carpenter and £78 9s

11d for repairing the gate of Bamburgh by the testimony of Henry

Sunderland and Peter Estreit. Additionally provisioning the

garrisons of both Bamburgh and Newcastle

cost £100. This large sum suggests that more than mere

repairs to the gate were carried out, some £80 would have been

sufficient to build a small tower. Perhaps this saw the

construction of the rectangular chamber on the east side of the great

twin towered gatehouse.

On 12 May 1236, Hugh Bolbec (d.1262) was appointed custodian of Northumberland with the castles of Bamburgh and Newcastle.

He soon wrote to the king that his salary was both insufficient for the

job and in arrears, so it was impossible for him to have the buildings

and turrets of Bamburgh castle repaired, the wall raised in one place,

a new turret built in another, the one that was half completed finished

and the great grange repaired so that it did not collapse. All

these works had been urged on him by royal letters and 2 household

knights, Richard Fitz Hugh and Simon Brumtoft. However, it was

estimated that these works would cost over £200 and the money

simply was not available.

In September 1237, it was recorded, without cost, that the rock next to Bamburgh castle barbican had been excavated (concavanda),

a grange and bakery built and the castle bridge repaired. This

seems to have been in response to a command to repair the grange and

bakehouse of the castle on 16 May 1237. These works were caused

by the simmering tension between Henry III

and Scotland. This mistrust was brought to an end that September

and on 28 September 1237 the king wrote to his constables of Bamburgh

and Newcastle that a firm peace had been

made with the king of Scots so that the king ‘is not now in fear

of his castles as before' and so Hugh Bolbec was ordered ‘to

spend as little as he can on these castles'. Regardless of this,

in November or December 1237 Sheriff Bolbec wrote again to Henry III (1216-72) that he had received the king's command to carry out repairs to Bamburgh and Newcastle,

but that the county did not supply sufficient funds for this and that

he had not been paid the 200m (£133 6s 8d) which he should have

been for keeping the county and the castles for a year since Michaelmas

last. Despite this he had paid the crossbowmen at Bamburgh and

repaired 2 bridges at the castle. Two years later at Michaelmas

1239, the sheriff recorded that he had spent £18 4s 9½d

‘in repairing the king's mill at Bamburgh and the king's chamber

of the king's old hall and the king's old kitchen to the same hall

pertaining to Newcastle' (in

repatione molendino regis de Bamburc et cameo regis vetris aule regis

et vetris coquine regis ad eandem aulam p'tin in Novo Castro supra Tynam).

He also spent a further £3 9s 4d on amending the king's houses in

Bamburgh castle. In 1240 he further amended the king's houses of

Bamburgh and Newcastle for £8 3s

9½d and in 1242 he did the same for £3 11s 11d. In

1243 it was recorded that £9 13s 9½d had been spent on

amending the king's houses in Bamburgh and Newcastle,

while a mill had been thrown down by the wind at Bamburgh and had had

to be repaired for £12 13s 9½d. The mill had been

blown down by a storm before 27 April 1243. Whether this was the

windmill in the castle west ward or not is another matter, but the

king's mills of Bamburgh were ordered repaired again on 9 May 1250,

which was done by September 1252 at a cost of £33 15s 9d.

The next year on 10 August 1244, the sheriff was ordered to let Gerard

the Engineer have what he needed while he repaired the king's castle

crossbows at Bamburgh and Newcastle.

These crossbows needed further maintenance by 25 October 1249.

Once more in 1245, £9 5s 2d was spent on amending the king's

houses in Bamburgh and Newcastle.

On 29 July 1249, the sheriff was ordered to spend up to 40m (£26

13s 4d) on repairing and improving the king's castle of Bamburgh.

In 1250, £17 9s 8d was spent in repairing the tower of Elmund's

Well in the castle and the barbican before the gate of St Oswald.

This was in reply to the sheriff being ordered to repair this tower and

barbican on 20 April 1250. The next year on 17 October 1251, he

was also ordered to carry out any necessary repairs on Bamburgh castle

hall. This was done by September 1252 when it was recorded that

£15 8s 9d had been spent on repairing the king's houses in the

castle over the past 4 years as well as £33 15s 9d on repairing

the king's mill this year.

On 31 May 1253, the sheriff was ordered to mend and repair where

necessary the great tower, the 3 gates within the castle with their

doors, locks and fastenings as well as the great swing bridge outside

the great gate to the south. On 13 November 1255, the sheriff was

ordered to repair the king's buildings of Bamburgh castle ‘where

absolutely necessary and at the least cost possible'. This

resulted in an expenditure of £39 14s 5d on repairing the houses

of the castle as well as repairing 2 turrets in the fortress with lead

at a cost of £8 2s 4d, while other repairs had cost 40m

(£26 13s 4d) by September 1256 and £3 1s 7d had been spent

by September 1258 on repairing the hall. In the summer of 1263,

the king, finding many of his barons unfaithful, ordered the castle

prepared for defence when it was learned that the kings of Denmark and

Norway were prowling the outer islands of Scotland with a great

fleet. Presumably this was the fleet eventually destroyed at the

battle of Largs by King Alexander III (1249-86).

From 3 May 1266, the cost of maintaining the garrison of Bamburgh

castle for 1 year was £1,231 9½d. It also seems that

Bamburgh was one of the few castles to remain constantly under the

control of the royalists during the Barons' War. It is to be

wondered if some of this immense cost was not simply exploitation of a

weak and incompetent king. When Edward I

(1272-1307) arrived back from Crusade in 1274 he immediately carried

out an inquest on fiscal abuses that had gone on during the end of his

father's reign. This discovered that William Heron [made

constable in 1248] had purloined some £5 when he had charged the

Crown £9 for building a granary at the castle which should have

cost no more than £4. Worse still, the current constable,

Robert Neville [of Raby, d.1282] had charged

the exchequer 1,200m (£800) for works at the castle that could

have been done for 200m (£133 6s 8d). As a consequence of

this Robert was relieved of his constableship on 7 June 1276.

The castle played an important part in history in 1296 when King Edward summoned King John Balliol

to meet him at Bamburgh to avoid war. After his victory over

Balliol, Edward halted at the castle on his triumphant return from

Scotland on 20 September. On 12 December 1299 and 1 January 1300,

King Edward was again at

Bamburgh. During the 9 years he was constable (1295-1304), Earl

John Warenne expended £570 on the munitioning of the fortress and

the repair of the castle houses. The bulk of this was still owed

to his executors several years later.

On 23 November 1307, Edward II (1307-27) granted to Isabel Beaumont, the widow of John Vescy of Alnwick,

the custody of Bamburgh castle with the truncage due to it and the rent

of Wearmouth town for her life. This was all for a rent of

£110 annually and the condition that she repaired at her own cost

the houses, gates, bridges and walls of the castle as well as sustained

the gatekeepers and watchmen of the place. Then on 6 November

1307, King Edward II ordered

her to release, at her own request out of piety, 8 Scottish prisoners

held in Bamburgh castle. They were also to have their wages paid

as well. All of these had been taken prisoner during the reign of

Edward I (1272-1307). On

19 December 1307 and 6 April 1308, the king ordered the fortifying and

guarding of many castles throughout England. This of course

included Bamburgh. On 12 March 1310, the king further conceded to

Isabel in consideration of her expenses in remaining in the company of

the queen of her payment of £110 yearly for Bamburgh as long as

she undertook the maintenance of the houses, gates, bridges and walls

of the castle and also the payment of the watchmen. The king

engaged to find victuals and other necessities in case of war and

further took on the expenditure of having the great and lesser towers

as well as the great outer ward maintained at his own expense.

The 1307 grant of Bamburgh to Isabel Vescy had gone against statute,

but the king's position was strong at the beginning of the reign.

This royal strength was frittered away as time passed, but the grant of

Bamburgh assured him of Isabel's loyalty and King Edward II stayed at the castle on 26 July 1311 during his Scottish campaign. Afterwards:

The king, fearing the envy

and hatred of the great of the kingdom of England for Piers Gaveston,

placed him in Bamburgh castle for his security, asserting that he had

placed him there to please his prelates, earls, barons and great men.

Therefore, in order to

preserve him [Gaveston] from the intrigues of the magnates, the king

shut him up in Bamburgh castle, asserting that he had done this to

appease the hearts of his friends. But this did not appear to be

enough to them, so that even this worst king suffered not a few insults

because of it.

Therefore in the year 1311 about 24 June [more likely 26 July

1311], he [Gaveston] was recalled from Bamburgh and entrusted to the

custody of Earl Aymer Valance of Pembroke (d.1324), whom he [Gaveston]

had previously compelled to swear by the sacred sacrament, standing in

his presence, that he would defend him, as far as he could unscathed,

against all his enemies, until the time came when he proposed to

reconcile him to the rest of the nobles by charter.

This of course did not happen and Gaveston went into exile after the

Autumn parliament on 3 November 1311. King Edward was furious,

but initially powerless. On 27 September 1311, he had assented to

the Ordinances being enacted, one of which stated that the Lady Vescy

should be banished from court for obtaining grants of land for her

brother, Henry Beaumont, and others to the disherison of the Crown and

that Bamburgh castle should be taken from her and not let out again

unless at the king's pleasure. Consequently on 18 December,

Isabel Vescy was ordered to hand Bamburgh castle over to Henry

Percy. Before things could settle down, around Christmas 1311,

the king suddenly recalled Gaveston to him at York, the friends probably meeting at Knaresborough

on 13 January 1312. A fortnight later on 28 January 1312, the

king wrote to Isabel Vescy as keeper of Bamburgh castle, stating that

he wished her to retain possession of the fortress, as he was

‘unwilling that Henry Percy, to whom he had granted it, should

have custody thereof'. After this there was some minor

campaigning in Yorkshire which set in motion events that led to

Gaveston's death on 19 June 1312 as related under Scarborough.

In the meantime on 16 May 1312, about a week after Gaveston's capitulation at Scarborough,

Isabel Vescy was commanded to yield Bamburgh to John Eslington and he

was ordered on 29 May 1312, to victual the castle with 100 quarters

(6,400 gallons) of wheat, 200 quarters (12,800 gallons) of malt and 300

quarters (19,200 gallons) of oats. The resumption of the castle

ended Isabel's association with Bamburgh, although on 25 November 1313,

it was recorded that Isabella, the king's kinswoman and widow of John

Vescy, had lately surrendered Bamburgh castle, granted to her for life,

to the king. The king wishes to know if she has also surrendered

the armour, victuals and other things in the castle.

John Eslington remained constable until his capture at Bannockburn on

25 June 1314. Three days later Roger Horsley was appointed by the

king's word of mouth to fill the now vacant position. Eslington

had proved a powerful constable which caused the locals of Bamburgh to

complain to the king that he refused to let them pay £270 to the

earl of Moray for a local truce unless they paid the constable the same

amount. Further, he charged them exorbitant fees for permission

to store their smaller goods in his castle and that his porters and

serjeants extorted money from them for merely entering or leaving the

fortress. They therefore found themselves reduced to the

bitterest of states trapped as they were between the Scots on the one

side and the constable on the other. Further, John the Irishman

and his fellows of the castle seized their provisions without any

intention of paying for them. The constable also seemed to

practising piracy against any who came near the castle by sea.

During 1315 a garrison of 20 men at arms and 30 hobelars were kept at

the castle under Constable Horsley at the king's expense while Roger le

Attallour was there improving the crossbows, bows and other

instruments. On 7 February 1316, Horsley was ordered to give

custody of the castle to William Felton, but was back in command by

1319 when he had a permanent garrison there of 15 men at arms and 30

foot, while the king was supplying a further 15 men at arms there under

David Langeton and Thomas Hedon. These latter 2 men had led the

garrisons of Bamburgh, Alnwick and Warkworth on a raid that took the peles of Bolton and Whittingham (Wytingham)

in 1318. A Scottish raiding army came near in 1322 as the king

wrote on 18 September stating his displeasure ‘with some men in

Bamburgh castle who held a colloquy with the Scots near the castle and

made a fine to save their houses and goods'. The king also

complained to Constable Roger Horsley of Bamburgh castle that he had

allowed a small force of Scots in ‘infest the area near him,

doing mischief and, what is worse, taking ransoms and hostages from his

subjects' and let them get away without challenge or damage from the

garrisons, to the constable's dishonour and shame as he had a much

stronger force that the king had spent so much in strengthening.

Consequently as they only amounted to 100 men at arms and 100 hobelars

the king was astonished that there were no proper scouts to even harass

or delay the enemy.

Around the same time Robert Horncliff was appointed constable. In

1329 he reported that the munition of Bamburgh castle consisted of 4

casks of wine and a pipe of Greek wine that had gone bad, 1 and a part

jars of honey, 7 targes - broken and unrepaired, an aketon of no value,

5 bassinets of no value, 7 crossbows with screws, one of whalebone and

with a case of new work, a dozen 1 foot crossbows, 4 buckets full of

quarrels, a bow and 5 sheaves of arrows, 7 baskets for bows, 12 baskets

for 1 foot crossbows of which 4 were of no value, 2 baskets for screw

crossbows, 10 one foot crossbows of no value, a teler without a nut for

a screw crossbow, 35 bolts for a springal of new work, 28 unfeathered

bolts for a springal - 4 without heads, 46 wax torches in a chest, 15

baldrics 4 of which had no fastenings, 360 leaves of whalebone, an old

brass pot containing 5 flagons, 10 pairs of fetters, a copper and a

mashvat in the brewery, a copper in the kitchen furnace, 2 tables with

4 pairs of trestles, a fixed table, 4 vats, a tun, a boulting tub, a

jar for putting bread in, 2 barrels, 2 sail yards, 2 windlasses and 4

ship's cables. Further, of this stock, 4 screw crossbows, 4 one

foot crossbows, a bucketful of bolts, the bow and 5 sheaves of arrows,

had been used up in the defence of the castle from Scottish assaults

from October to December 1328. As a result Horncliff

allocated £25 15s 3d on the most pressing repairs and reported

that it would take another £300 to put the castle in order with

work needed on the keep and all the other towers, hall, chambers,

grange and all the other houses and gates that were so roofless and

decayed. Otherwise the whole place would collapse into

ruin. On 8 Sept 1330 he reported that he had found that the lead

covering the keep was so old and decayed that rain had caused the main

beams to rot, threatening the tower with ruin. The stone roof of

Davies Tower (Davytoure) had been carried away in a storm as had that of the Bell Tower (Belletoure)

with the result that its timbers were rotten; the hall, great kitchen,

great grange and the towers called Vale Tipping, Dead House? (Dedehuse) and Colelfte

along with the granary, horse mill and great stable were in equal

decay. This was the result of previous constables not making any

allowance for repairs in their accounts to the Exchequer.

Apparently nothing was done to alleviate this state of decay.

In 1333 when Edward III (1327-77) was besieging Berwick,

the Scots, under Archibald Douglas (d.1333), trying to relieve the

pressure on the town, assaulted Bamburgh castle which was held at the

time by Queen Philippa (d.1369). The attack failed and Berwickfell

immediately after the battle of Halidon Hill in which Douglas

himself was killed on 19 July. After the war, from 1333 to 1335,

some £80 were spent on repairs according to the pipe rolls.

In the latter year, on 29 August 1335, the king gave the castle to the

custody of Ralph Neville (d.1367) of Raby

without any proviso for the maintenance of the castle, other than the

paying of its officers. The consequence of such a grant should be

obvious. Possibly it was made at the time when Edward thought the

conquest of Scotland was a foregone conclusion and therefore a large

royal castle on an ex frontier was no longer a necessiry.

Bamburgh castle was involved in

the next great Anglo-Scottish war too, when, after the battle of

Neville's Cross on 17 October 1346, King David II

(d.1371) was brought to Bamburgh castle where 2 barber surgeons from

York extracted an arrow from him and healed him, receiving £6 for

their work. It was only on 7 March 1347 that David was moved from

Bamburgh to the Tower of London. Some 10 years later, on 20 January 1356, King Edward Balliol (d.1364), completed the final surrender of the Scottish Crown to Edward III.

Afterwards, King Edward spent 10 days at the castle in February

1357. The castle then remained under royal custodians as a bit of

a backwater during the rest of Edward's reign.

On 14 June 1372, a commission declared that the executers of the will of Constable Ralph Neville of Raby

(d.1367) had done all the repairs that they could be charged with and

that over and above these they had been compelled by certain unknown

members of the king's lieges, to build and repair a wall, a tower

[Clock Tower?] and a turret [the elongated D shaped tower north of the

Clock Tower?] and Waltheof's Well (Waldehavewell)

within Bamburgh castle and also a postern [by the Clock Tower?] and

great walls there. The executors had further been forced to

repair the [inner bailey] wall stretching from Davies Tower (Davyestour)

to the west gate of the castle [Tower Gate], a postern at the Gaitwell

[Elmund's Well] and a great wall between the Smith Gate (Smetheyet) and Ravens Hall (Ravenshaugh, the hall by St Oswald's Gate?) and another long wall between the Smith Gate (Smetheyet) and the Vale Tipping (Vallam de Typpyng).

This extra expenditure was valued at £266 13s 4d. Some of

this work was entrusted to the ubiquitous Durham mason, John Lewyn, who

was also responsible for work at Carlisle

and other castles in the North. However in this case it was

claimed, on 9 March 1375, that he had received monies, but did not do

any work.

After all this hard work, further problems at the castle were reported

on 21 August 1373, when it was found that Constable Richard Pembridge

[who had taken over the castle in 1367 and died in 1375] had allowed

the well in the keep to become choked up with offal so that it would

take 40s to purify it, while its rope and bucket had gone to the king's

loss of 13s 4d. Meanwhile, William Scra, Pembridge's steward, had

taken away beds, chairs, tables, trestles, saddles, horseshoes, bows,

plates, dishes, leaden vessels and other things to the value of 10m

(£6 13s 4d). Further John Fenwick, who had been

subconstable under Pembridge, had stolen various things from the castle

including, after Sheriff Umfraville had taken possession of the castle,

the principal table and trestles from the great hall as well as 7

stones of lead and the ironwork for a mangonel from which he had

already stolen the wooden parts. An inquiry held 2 days later

found that 2 iron chains, an iron bolt, a lock and a small door at the

postern as well as an iron bolt for 2 barriers had decayed since the

time of Constable Neville (d.1367) while under Pembridge (d.1375) a

bridge within the castle had decayed which would cost 13s 4d to

replace. They also found that Thomas Heddon held lands called

Porterland within the demesne of the castle and had 2d daily paid to

him by the constable for his finding a porter at the gate at all times

and a watchman within the castle all night as well as his maintaining

the Porterhouse within the castle near the Vale Tipping. However,

the Porterhouse had been reduced to ruins during the time of his

predecessor, William Heddon and now could not be repaired for less than

£3. Also, during Pembridge's time, the roofs of the 4

chambers within the 4 turrets on the north side of the castle had

become so decayed that 12s would scarcely mend them. Further,

Pembridge had allowed 3 stables and the slaughterhouse to decay to the

extent of 20s and a boarding (bordour) over the Tower Gate (Tourgate),

valued at 12d, had decayed. Consequently, 40m (£26 13s 4d)

would hardly cover the neglect while a further 10s would be required to

carry out the repairs necessary since the castle was in the king's

hands.

In 1384 another Scottish raiding party visited the area with the result

that in November 1384 the castle constable, John Neville (d.1389),

undertook to repair the castle for 1,300m (£866 13s 4d).

His works included a new hall 66' long and 34' wide internally, with 3

windows on one side and 4 on the other as well as a vaulted porch at

the entrance. At one end of this was to be a vaulted chamber and

at the other a pantry, buttery, kitchen and other offices. Such a

layout was visible until the rebuilding of the hall block by Lord

Armstrong in the early 1900s. This work was probably completed by

the time of Neville's death in 1389, but was said to have cost 200m

(£133 6s 8d) more than the budgeted price.

Despite this work, on 26 October 1392,

Constable Richard Pembridge of Bamburgh, complained that there were

many defects in the castle and its great tower, as in houses, turrets,

walls, buildings etc and in mills, houses, buildings, ponds and the

likes... which happened when Ralph Neville (d.1367) was keeper and

constable and these were not repaired by him. The king therefore

commanded his executors to repair them as Ralph had had the issues and

was supposed to repair them. Repairs had since been done, but the

costs misapplied to the previous constable. In 1399 Henry Hotspur

Percy of Alnwick was granted the

constableship of the castle. When he was killed in rebellion at

the battle of Shrewsbury in 1403 the castle was passed to Earl Ralph

Neville of Westmorland (d.1425). His constable, John Coppyll,

reported on 13 January 1404 from Bamburgh that the castle and its

lordship were safe in his hands, but the castles of Berwick, Alnwick and Warkworth

were strongly held by William Clifford, Henry and Thomas Percy.

These were eventually taken and Bamburgh held securely for King Henry,

although the fighting continued in Northumberland until 1408.

In 1419 war between England and Scotland resumed with the Scots knowing

that Bamburgh castle was under garrisoned. Therefore Constable

William Elmeden hired 6 men at arms on 8 September at 1s per day and 12

bowmen at 6d at his own costs for 2 years until peace was

restored. Further, he spent £66 8s 8d in repairing the

castle, especially the north wall next to the gatetower as well as the

bridge and well there, 2 ovens in the baker's house, 2 lead coppers in

the brewery, the north wall next to the postern, Neville's chamber, the

hoardings (rakkys, racks) for

defending the walls and the walls of the Vale Tipping, as well as the

Reed and Maiden towers, which were found to be in no condition to repel

enemy attacks. With this the castle slipped back into obscurity.

Bamburgh proved a pivotal position in the opening stages of the Wars of

the Roses. In the summer of 1461, after the Lancastrian defeat at

the battle of Towton, Bamburgh castle must have surrendered to the

Yorkists, possibly around the time William Hastings (d.1483) took Alnwick castle

that September. The fortress remained in Yorkist hands until

October 1462 when Queen Margaret (d.1482) returned from France with

6,000 French soldiers. She first took Bamburgh castle and then,

leaving Ralph Percy (d.1464) to defend Bamburgh, besieged and took Alnwick in November. On 1 November 1462, John Paston Junior wrote from Holt castle

to his father stating that he had heard that William Tunstall was taken

with the garrison of Bamburgh castle and that William was likely to be

beheaded at this will of Richard Tunstall, his own brother. The

result was that in December 1462, Edward IV (d.1483) in person marched

on the 3 rebel castles of Alnwick, Bamburgh and Dunstanburgh and placed them under siege on 10 December.

King Henry VI (d.1471) and Queen Margaret (d.1482), had fled from

Bamburgh castle by sea in November 1462. This left Duke Henry of

Somerset (d.1464), Earl Jasper Tudor of Pembroke and Ralph Percy

(d.1464) within. They were soon besieged by lords Montagu

(d.1471) and Robert Ogle (d.1469), with the earls of Worcester and

Arundel appearing later. Warwick supervised operations from his

base at Warkworth castle, riding to all 3 sieges each day, while Norfolk was in charge of bringing supplies up from Newcastle to Warkworth, with the king waiting for a Scottish invasion from his base at Durham. On Christmas Eve 1462, both Bamburgh and Dunstanburgh

castles surrendered on the garrisons being granted their lives and

members and the condition that Ralph Percy (d.1464) should be restored

to Bamburgh and Dunstanburgh castles

as soon as he paid homage to King Edward IV. The Bamburgh

garrison consisted of Duke Henry of Somerset, Earl Jasper Tudor of

Pembroke, Lord Roos and Ralph Percy together with some 300 men.

The surprisingly lenient terms were partially due to the news that a

Scottish relief army was heading into Northumberland.

The peace proved short and early in 1463 Ralph Percy (d.1464) changes sides again, taking Bamburgh and Dunstanburgh castles with him. At this point Warwick marched north and sent a Scottish besieging force at Norham castle

scampering back across the border. Despite this, the 3 major

Northumberland castles were left under Lancastrian control. A

year later in the March of 1464, Somerset with Ralph Percy attacked and

took the castles of Bywell, Hexham, Langley, Norham and Prudhoe.

However, Montagu twice defeated the rebels and Somerset and William

Tailboys were finally executed after the Lancastrian defeat at Hexham

on 15 May 1464. King Henry VI, probably in the company of Ralph

Grey who had quit the field of Hexham before the battle began, fled

back to Bamburgh castle where on 31 May a small band of lords

‘adhered unto Henry of late called king'. Henry himself was

captured, at Waddington Hall in Lancashire on 13 July 1464 within a

month or 2 of having left Bamburgh castle from where he had been ruling

those places still loyal to him in the North during the last

year. During this summer the earl of Warwick had moved against

the remaining rebel castles. First Alnwick and Dunstanburgh

surrendered on 23 June 1464 without a fight, allowing Warwick to move

on to Bamburgh castle which he called on to surrender on 25 June

offering pardon to all but the commanders, Grey and Humphrey

Neville. Grey replied that he had ‘clearly determined

within himself to live or die within the castle'. The herald

replied that his lords had announced that the king wanted this

‘jewel' to be whole and unbroken with its ordinance, as it stood

so near to his Scottish enemies, but if he had to fire upon it, it

would cost the leader his head and for every other shot fired upon it a

member of the garrison would be beheaded until none remained if needs

be. With that Warwick ordered the bombardment to begin. The

great iron guns Newcastle and London hit the castle so that ‘the

stones of the walls flew into the sea'. Meanwhile Dysyon, a

brazen gun, repeatedly smashed through Grey's chamber. After 2

days the castle was surrendered and the wounded Ralph Grey was taken

before Edward IV at Doncaster, charged with withstanding the king's

majesty ‘as appears by the strokes of the great guns in the

king's walls of his castle of Bamburgh'. Humphrey Neville, who had

surrendered the castle rather than the wounded Grey, was pardoned, but

the turncoat Grey was executed that July. With this Bamburgh was

patched up as a Yorkist fortress once more.

In 1480 Edward IV went to war against James III of Scotland

(1460-89). This resulted in Earl Archibald Douglas of Angus

(d.1514) leading a punitive expedition into Northumberland that summer

which reached as far as and supposedly burned Bamburgh castle.

The castle was apparently not in a good condition by the time of the

Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536. Parts of this war are described

under Bolton castle. Consequently,

after the rising had been put down, on 13 April 1537, orders were given

to repair and furnish the border fortresses of Alnwick, Bamburgh, Berwick, Bewcastle, Carlisle, Harbottle, Newcastle on Tyne, Scarborough and Wark or some other fortress in Tynedale. Barnard Castle, Knaresborough, Middleham, Pontefract, Sandal and Sheriff Hutton were to be repaired to receive the king in person, while Cockermouth, Conisborough, Dunstanburgh, Penrith, Pickering, Prudhoe, Richmond, Tickhill, Warkworth,

Wilton and Wrestle were to be repaired . One result of this was

that on 22 February 1538, a view as taken of Bambrugh castle by Richard

Bellysys, Robert Collyngwod, and John Horslye. They found that:

Bawmborgh

is of 3 great wards and in great ruin and decay, albeit the situation

and standing of the castle is of the strongest and impregnable.

These things are the most needful to be done. First, the

drawbridge at the entrance of the east ward must be made anew and that

will cost 40s. Also there must be a new gate of wood with seym and royve

for the gatehouse at the entrance of the said drawbridge of 4½

yards height and 3½ yards breadth, which will cost by estimation

£5. Also the walls of the 2 outer wards are very much in

ruin and decay albeit that the ground and situation of them is

marvellously strong so that if there were but £40 spent in

diverse places of the walls where most needed it would do much

good. Further there must be an iron gate made for the inner ward

4¼ yards in height and 3¼ yards in breadth which will

take 2 tons of iron £10. Also for the smith making the iron

gate £6.

There is a great chamber within the inner ward that will

serve very well for the hall where the leads of the roof must be new

cast and a fother of lead more towards the mending of the leads and the

casting and the laying and the workmanship £3. There must

be for the hall 2 doors and 2 windows which will cost 20s. Half a

rood of skirting board for the hall 6s.

There is another fair chamber joining the north side of the

great hall which must have a new baulk of 6½ yards long which

baulk must be had from Chopwell wood... and which must be carried by

water, all charges thereof 12s. There must be for this chamber

half a rood of skirting board 6s. The leads of the roof must be

new cast and a fother of new lead more towards mending it. And

for gutters, spouts and fillets and the casting and laying 48s.

There is a fair vault under the hall and chambers convenient for a buttery, cellar and storehouse which must have new doors 20s.

There must be a new roof made for a house at the east end of

the hall which must serve for the kitchen and larders. Under the

house is a fair vault which will serve for the stable of 24

horses. And for making the roof there must be 6 baulks of 8 yards

and for various wallplates, spars and other timber for the roof 16 tons

of timber... carrying and making £7. For covering the roof

5 rood of slates with lattes, broddes

and lime will cost £6. For the kitchen and larder for

windows, doors and partitions 53s 4d. There must be for the

stable above for 24 horses, bays, mangers, racks and a door... for

carriage and workmanship £4.

There is a narrow tower [Muniment Tower] of a convenient

length at the east side of the kitchen which will be 2 chambers for

lodgings and must have 12 geystes of 3½ yards long and a rood of

skirting board for 40s. The roof of the house must be new theykyd with lead and must have 2½ fothers of lead more than there is of it. For the casting and laying 24s.

There is a little tower at the south end of the kitchen

whereof the leads of the tower must be new cast and half a fother of

lead... 12s. For the same tower a rood of skirting board

12s. For the floors of the tower a rood of flooring boards

14s. For the tower doors and windows, locks and bands for doors

20s.

There are 2 fair chambers well walled joining both together

standing at the east end of the old walls called the king's hall and

under the 2 chambers there are 4 fair vaults and the 2 chambers must

have new roofs of 5 baulks of 8 yards long for either of the 2

chambers. And the rest of all manner of timber for the roofs of

both chambers will be 30 ton of timber... to be carried by water...

£14. For covering the 2 roofs 10 rood of slates which will

cost with lime, lattes, broides

and other necessities £13.... doors, windows, locks and keys etc

£4. There must be half a fodder of lead for a gutter,

plumbers' wages 3s.

There is a brewhouse and bakehouse both under 1 roof which is

decayed... a new roof of baulks 6 yards long and for all other timber

appertaining to the roofs 14 tons of timber... by estimation

£6. For covering the house with slates 4 rood which will

cost with lime etc £5. For doors, windows, partitions and

locks for the houses 20s. For making ovens, ranges, furnaces and

brewing vessels for the brewhouse, £8. There must be

1½ fothers of lead for making the brewing leads. There

must be a horse mill £10.

There are 2 draw wells, one in the donjon with donjon roof is

all decayed and the well of a marvellous great depth. The other

well [Elmund's Well] is in the west end of the west ward and the wall

that encloses the well to the castle must be amended for the mending

and cleaning of the well £4.

For repairing and mending both of divers fair towers

and for the walls of the inner ward that is to say for battlements and

for putting in of archelare stones and for pinning (pynynge) with stone where the walls are rent and rough casting of the said walls with lime some £40.

There are 4 towers within the inner ward whereof the walls

are very good and the timber of the roofs fresh and the lead of the 4

roofs must be new cast and there must be 3 fodder of lead more for

mending the roofs... and for gutters, spouts and fyllettes, £4.

Divers of these houses must be dyght and cleaned for there is

a great substance and quantity of sand within them which has filled

many of the said houses. And for labour and carrying it out

£4. Sum total £210 10s 4d and over and above that sum

there must be 10 fother of lead.

It would seem likely that little or nothing came of this, for on 24

October 1575 another survey was carried out of Bamburgh castle.

This was after a border skirmish at Redeswire Fray on 7 July

1575. The survey found:

Bamburgh castle is in utter

ruin and decay, the drawbridge and gates are so broken that there is no

usual entry on the forepart save at a breach in the wall that has been

well walled and yet has walls much decayed standing and is of 3 wards

in the 2 outer wards whereof nothing is but walls much decayed.

In the innermost ward is one tower 25 yards square by estimation

standing upon the top of the rock and in the same a well of fresh

water. The walls thereof are upright but much ruined and decayed

with weather. The roof whereof which has been timber and some

time covered with lead as it seems is utterly decayed and gone.

Within the ward have been the principal lodgings of the house and as

yet may appear all the offices belonging thereunto which for the more

part as it seems have been long in decay and the ruinous walls do in

the most part stand. And yet in one part of the same lodgings has

been of late a lodging for the captain, the parts whereof called the

hall and great chamber have been covered with lead and yet have some

lead upon them and in some parts revin and the lead taken away.

The hall in the captain's lodging contains in length 11 yards, in

breadth 7 yards, has lead upon it yet.... fothers. The great

chamber containing in length 10 yards and in breadth 5 yards has lead

yet remaining... the rest of the lead of both houses decayed and taken

away. The timber of both houses is perished and much

decayed. Within the ward of late a chapel and other little

turrets covered, all which be now utterly decayed saving the .... walls

of the most part thereof, much worn with weather, stands.....

To the castle also belongs a certain piece of ground which it seems has been enclosed, because there remains yet about it the me'cye [messee for mess?] where the ditch has been...

For the decay of the castle..... in the time of Sir John

Horseley late captain of the castle and at his death there was in the

castle a hall, a great chamber and one other chamber on the east side

of the hall, all covered with lead and furnished in other reparations

at that time convenient, to be dwelled in and that there was at that

time 2 other chambers in the castle likewise covered with lead and in

like reparations. And there was in the castle a kitchen covered

with flag and a chapel covered with slate and that under the said hall

and great chamber were cellars for offices with doors and all such

other furniture as was convenient....

Which lodgings are now in utter decay, the chapel timber and

stones clean taken away and all the other buildings before mentioned,

save only the hall and great chamber which have yet some lead upon

them... the timber by reason of the lead taken away, is much perished

but by whom the same spoil was done they know not.

The decay of the castle is before declared and what the

repair thereof will cost they know not, but if it shall be to any

purpose, to restore the former strength and beauty thereof, the charges

will be great. And they say that to their knowledge the queen's

majesty is to repair and maintain the same, because it is the ancient

inheritance of the Crown.

In 1584 John Forster (d.1602), who also spoiled Alnwick and Warkworth,

was charged with having lain waste Bamburgh castle. John had been

granted the possessions of the cell of Austin canons at Bamburgh in

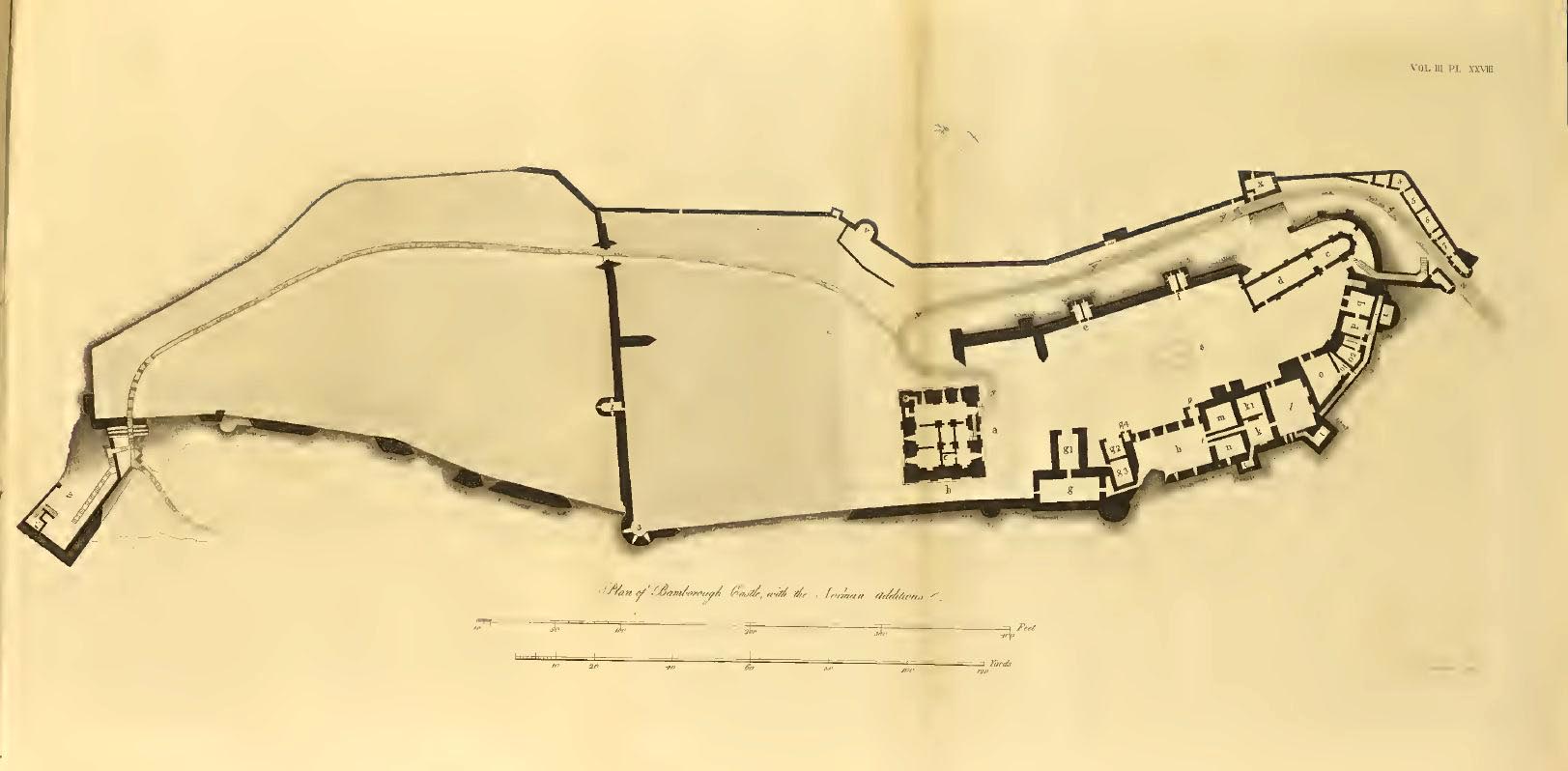

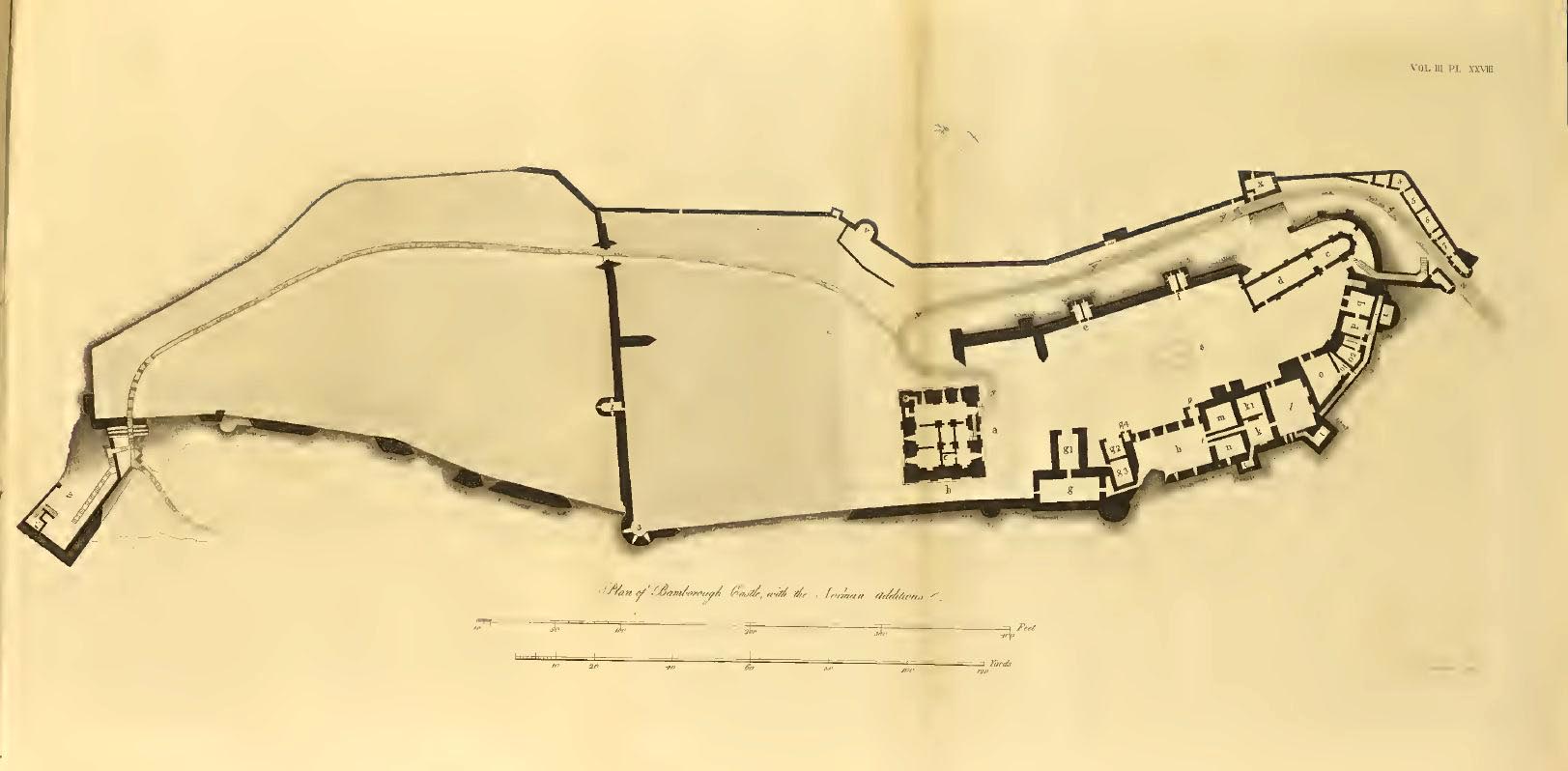

1545. His grandson held the fortress in 1704 when he sold the

ruins to Lord Crewe. It was from 1757 made habitable after his

death by Dr. Sharpe, the trustee of the charitable trust endowed by his

will. The donjon was repaired by 1766 when Sharpe entertained the

bishop of Durham to dinner in the keep court room. In 1769

Pennant recorded that Dr Sharpe had:

repaired and rendered

habitable the great Norman square tower; the part reserved for himself

and his family, is a large hall and a few smaller apartments; but the

rest of the spacious edifice is allotted for a purpose which makes the

heart glow with joy.... The upper part is an ample granary from

whence corn is dispensed to the poor without distinction, even in the

dearest time... Other apartments are fitted up for shipwrecked

sailors and bedding is provided for 30, should such a number happen to

be cast ashore at the same time.

In the early 1800s the outer wall towards the sea was rebuilt, followed

by the conversion of the great hall and kitchen into school buildings

in 1810. In 1817 strong westerly winds stripped the sand away