Tynemouth

Tynemouth has a long, if not particularly eventful history.

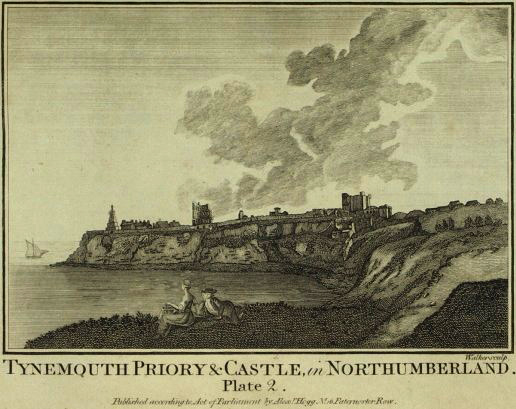

The site was certainly a priory, but one that always seems to have had

a defensive aspect. This is due to the fact that it stands upon a

cliff of Magnesian Limestone that projects boldly into the North Sea

and guards the northern side of the Tyne estuary. The rock it

stands upon has precipitous falls to east and north, but a less abrupt

slope to the south that leads, via a now destroyed cliff, to a small

harbour. To the west, sand and soil appear to have accumulated to

mask the precipitous approach to the castle rock on this front.

The summit of the rock was duly fortified and within these defences a

monastery was also constructed, forming three distinctive features of

the site, priory, castle and parish church. These 3 elements are

so entwined it is impossible to tell the full story of one without

delving into the history of the others. Briefly, excavation has

proved that a prehistoric settlement stood on the site with 2

roundhouses having been uncovered, one being pre-Roman the other from

the second century AD.

It has been suggested that a Roman fortlet stood here to complement Arbeia

on the southern bank of the Tyne. The only evidence for this is a

Roman altar, possibly reused as a foundation block. This was

found 6' below the ground surface north of the priory church in

1782. However, the altar appears to have originated from Segedunum

judging by its inscription. The next year, near the same place, a

slab was found bearing an inscription suggesting that it came from a

temple. Possibly such a structure stood on the site - a Roman

tile inscribed Leg VI v having been found in a trench before the castle

in 1856 as well as coins of Constantius II (337-61) and Magnentius

(350-53), but again no solid remains have ever been discovered.

It should also be remembered that various projections into the North Sea

have held Roman fortlets, the most well known being Scarborough. Otherwise the site has been very tentatively linked to the Roman station of Tunnocellum and the hermitage of Tunnacester, the latter being mentioned by Bede.

Whatever early works stood at Tynemouth they were superceded by the

seventh century church. Whether the fortress was always under the

control of the monks or not is open to question, but by the Norman era

this seems to have been true. Certainly the ‘castle'

withstood a 6 day siege in 1095 before the garrison was forced back

into the church. During the Edwardian troubles with Scotland the

castle was refortified and again towards the end of the fourteenth

century when raiding this far into England was still a problem.

With the dissolution of the monasteries during the reign of Henry VIII

(1509-47), the nave of the priory became the parish church and remained

so until the Civil War of 1642 to 1649. The rock girt site,

however, remained active militarily right up to its abandonment in 1960.

It can therefore be seen that the history of Tynemouth is

complex. There was once an early Medieval chronicle of Tynemouth,

seen by Leland in the 1540s. This might have expounded much of

the castle and church history, but sadly is now lost. However,

Leland did make a few jottings from the text which recorded that it was

written by an anonymous monk from St Albans (Albanensi). As his few lines are all that has survived of the text it is worth translating and publishing here.

The author of the chronicle was a St Albans monk, but his name is uncertain.

Oswin king and martyr was buried at Tynemouth.

Edwin king of the Deiras was buried there.

Henry the hermit of Coquet Island was buried there.

King Malcolm of the Scots was slain at Alnwick by Earl Mowbray and was buried there in the chapter house.

King Edwin of the Northumberlanders erected Tynemouth chapel

from wood, in which Rosella his daughter afterwards received the veil.

St Oswald made the monastery of wood and stone.

Tynemouth monastery was twice destroyed, once by Ivar and Hubba (Anger and Hubon) and again by the Danes in the time of King Æthelstan.

The Danes used Tynemouth as a stronghold and even a shelter when crossing from Denmark and Norway into England.

On the island of Coquet is the convent of the monks of Tynemouth...

Next to Tynemouth was a city destroyed by the Danes called Arbeia (Urfa on the other side of the Tyne), where King Oswin was born.

The place where the convent of Tynemouth now stands was anciently called Benebalcrag by the Saxons. Penabalcrag is the correct form, meaning The Head of the Valley on the Rock; for near this place was the end of the Severian Wall.

Judging from the above, the Tynemouth chronicle was possibly late

eleventh or twelfth century in composition, but probably utilised older

works or folk memory for the Saxon era. If correct, Leland's

notes on the chronicle would suggest an early seventh century date for

the founding of the religious establishment. To support this

contention, fragments of Anglo-Saxon crosses have been excavated both

in and just outside the priory church. Further, excavations in

1963 and 1980 uncovered the postholes of 5 rectangular timber

buildings. These have been interpreted as part of undefined

wooden buildings of the early monastery. Sadly no datable finds

were recovered and, possibly significantly, no certain trace of the

early monastery. This may suggest that the masonry is in fact

much older than twelfth century as the chronicle fragment indicates.

Of great importance to the later Tynemouth, King Oswin was murdered on

20 August 651, and is then supposed to have been buried at

Tynemouth. King Edwin of Deira, the claimed founder of Tynemouth

and uncle of King Oswin, reigned from about 616 until his death at the

battle of Hatfield Chase on 12 October 633. That he was buried at

Tynemouth and that his daughter is alleged to have taken the veil here,

again suggests the close link with his family and their likely

foundation of this house. It should also be noted that Edwin was

the first Christian monarch of the district, being converted in

627. Presumably the wooden Tynemouth was built soon after this to

be replaced by Oswald, the eventual Christian successor to Edwin, with

a building of stone and wood. Quite what this meant, stone walls

and wooden infrastructure, or even wattle and daub construction, cannot

now be ascertained. Oswald ruled from 633 until 5 August

641/2.

Against the tradition recorded above, Lindisfarne

monastery, some 50 miles to the north, is only alleged to have been

founded in 634 at the request of King Oswald, while between 651 and

661, a timber church is said to have been built there ‘suitable

for a bishop's seat'. This has often been taken as the first

Christian church built in the north. The Venerable Bede bemoaned

the fact that the church was built of oak and thatched with reeds

rather than being a proper stone building. Abbot Eadbert is later

said to have removed the thatch at Lindisfarne

and covered the whole building, walls and roof, in lead! The

early foundation of Tynemouth is mitigated against by Bede himself who

states that no church was ever built in Northumbria until King Oswald

raised his cross at Heavenfield in 633. If this is correct, it

seems most likely that Tynemouth was founded by King Oswald (633-41),

perhaps initially as a stone church. Bede later writes of

Herebald (d.745) as abbot of the monastery at the mouth of Tyne. This

of course would mean that the Oswin and Edwin stories were later

inventions. In 792 King Osred, returning to Northumbria, was

waylaid and murdered, being buried at Tynemouth on 14 September.

Quite obviously it is impossible to tell which of these stories were

true and which later invention.

In the eighth century Viking attacks began on the coasts of

England. Even what happened here is problematical. Two

attacks are said to have been made on Tynemouth in the chronicle.

The text, as copied by Leland, apparently missed at least one attack on

the monastery which, according to Matthew Paris (d.1259), happened in

800.

The army of the heathen cruelly plundered the churches of Hackness (Hertenes) and Tinemutha, and returned with the spoils to the ships.

Possibly the church was sacked then, if any attack took place. A

coin of Ethelred II of Northumbria (841-844) was excavated from the

hilltop in the 1963, which suggests that the site continued in

occupation. Other than this, the first recorded destruction of

the monastery in its chronicle can be reliably dated. It must

have happened after 865, when the 2 brothers mentioned appeared in East

Anglia and 870 when Ivar left Northumbria for Ireland. Ivar died

in Ireland in 873, while Ubba died in 878. The Durham chronicle

records under the year 867 that the Great Pagan Army followed the

Humber from York laying waste everything to Tinemutham.

Again it is only Matthew Paris (d.1259) who notes the destruction of

Tynemouth and the other monasteries in 870 after Ubba's Scottish

campaign. As this campaign only occurred in 874/75 and is linked

to the brutal evangelism of Abbess Ebba of Coldingham, like the early

foundation of Tynemouth, it is probably a fabrication.

Before this second alleged sacking, there are modern claims that the

monastery was able to defend itself against a Viking attack in

832. Where this information has come from originally is hard to

judge, but there seems to be no substance to the contentions.

According to the Tynemouth chronicle a second destruction of Tynemouth

monastery occurred during the reign of King Æthelstan

(925-39). This implies that the church was rebuilt or at least

still operational during the 50 odd years since 870. It is also

plain from the chronicle that it was thought that the place was

fortified by the Danes after they occupied the site, presumably as a

base above the harbour. Possibly then, the Vikings were the first

to fortify the site. Against this is the possibility that a Roman

fortlet stood upon the site which had earlier been a hillfort of

sorts. Again this parallels what seems to have gone on at Scarborough.

Tynemouth church must have been repaired after the alleged Viking

destruction, but only had a single custodian until the

‘discovery' of the body of St Oswin on 11 March 1065. Two

stories exist about this event. One twelfth century account

states that it was found in a Tynemouth oratory after a standard

miraculous dream and allegedly at the urging of Countess Judith

(d.1094), the wife of Earl Tostig (d.1066). This tale of the

finding of the saint was compiled at St Albans in Hertfordshire after

1111 when the author himself, a former prior of Wymundham, was at

Tynemouth recording the rather mundane miracles of St Oswin at his

leisure. In this account the body of Oswin was translated on 11

March 1065 at which time the church was obviously serviceable.

Further, the calamities that befell Earl Tostig (1055-65) on 3 October

1065, when he was ousted from power, were said to have been caused by

his neglect to attend the translation of the saint. Despite these

claims, Simeon of Durham recorded how a semi-professional saint finder

from his own monastery, their sacrist Alfred Westou, is said to have

found the saint's remains under the church floor. This is surely

more likely. Also, the fact that the church was still standing

and functional in the reign of the Confessor (1042-66) helps give the

lie to the idea that the Vikings destroyed all the churches of the

North. This seems to be a myth peddled by twelfth century

chroniclers, but not recorded during the time of the Viking attacks and

settlement.

Tynemouth church was definitely standing and made of stone in 1070. In that year the Vita Oswini states that William I (1066-87) was camped at Monkchester - later to become Newcastle upon Tyne

- when one of his foraging parties came to Tynemouth and seized the

provisions there before burning the church. Simeon notes that

Tynemouth church had been roofless for 15 years in 1085.

At that time count [Waltheof] himself was at Tinemuthe, which place he entrusted to the monks [of Jarrow], themselves to be disposed of together with the aforesaid little one [church].

Between 1065 and 1085 the earldom Northumberland went through many

vicissitudes and damaging military activity. The monastery at

Tynemouth is said to have been refounded by Earl Robert Mowbray of

Northumberland. According to Matthew Paris, the St Albans'

historian writing midway through the reign of Henry III (1216-72):

Concerning the monks first introduced to Tynemouth

[Robert Mowbray], with the advice of his friends, Abbot Paul

of the church of Saint Albans, summoned an assembly... At whose

request the aforesaid abbot, agreeing with them, appointed some of the

monks of St Albans to that place; which the aforesaid earl, when he

himself had sufficiently provided it with manors, churches, rents and

fisheries, with mills and all things, which he confirmed with his

charters all the aforesaid things, free from all secular service, and

completely free; he gave the church of Tynemouth, with all its

appurtenances, to the aforesaid Abbot Paul, his successors and the

protomartyrs of the church of the blessed Alban of the English, for

their own health and for that of all their ancestors or successors, to

possess eternally; in such a way that the abbots of St Albans who were

in that time, with the advice of the assembly of the same place, had

free disposal of the priors and monks, such as to place them or to

remove them from there, as they saw fit.

Although this statement by Paris may have contained a cornel of truth

such charters by Earl Mowbray probably did not exist, or if they did

they were destroyed in 1174 when Tynemouth surrendered their charters

to bring an end to the hostility with Durham priory. In any case

in 1292 a monk from Tynemouth priory commented in the St Albans'

register ‘God knows what has become of it'. The

falsification of non-existent charters was quite a boom industry in the

twelfth century when literacy was becoming more important to

landholders.

The early history of Tynemouth priory is therefore entwined with the

career of Robert Mowbray. He did not become earl of

Northumberland until 1086, when Aubrey Coucy probably resigned control

of the district to the king. The most likely series of events is

that Tynemouth was at this time thought of as a daughter house of Jarrow

and that the latter and just possibly the former, had been refounded in

the early 1070s. A suspect copy of a single charter of Earl

Waltheof (d.1076) survives about this, although there is a distinct

possibility that this is a twelfth century forgery by the monks of Durham.

Certainly this only exists amongst the Durham priory charters and the

Durham monks had a history of forgery to support their territorial and

political claims. That the text is not a true copy is confirmed

by one of the witnesses being Earl Aeldred, a man who had died in

1038. Further, the confirmations of Durham's lands by William I (1066-87), which precedes the Tynemouth confirmations mentioned above, are also reckoned forgeries.

If there is any truth in the Tynemouth charter, it was probably made

soon after 1072 when Waltheof was appointed earl, and probably 2 years

since the Conqueror's troops had burned the roof off Tynemouth church -

a roof said to have been repaired by a monk from Jarrow, possibly at the bidding of the brethren of Durham

during the Conqueror's reign. The charter runs that Earl Waltheof

of Northumberland (1071-75), in the presence of Bishop Walcher

(1071-1080) and the entire synod of the bishopric of Durham, gave to

Prior Aldwin (1073/4-83) and his brothers at Jarrow,

the church of St Mary of Tynemouth, with the body of St Oswin resting

in that church, with all places and lands etc which pertained to it,

free and quit forever. And with this he offered the boy, Morkar,

to the church in the service of God. There is then a long closing

clause confirming this gift and then no less than 22 witnesses to it,

about double those of any other charter. Earl Waltheof is also

said to have founded Durham castle in 1072,

so attempting to repair the damage of the Harrying of the North may

have been paramount in local minds. At this time the religious

reformers Aldwin, Elfwine and Remfry, were beginning their

administrations in the North settling first at Monkchester and then at Jarrow

whose church they repaired after being granted it by Bishop Walcher

(1071-1080). This again fits in quite well with a grant of

Tynemouth to the newcomers at Jarrow between 1072 and 1074. The

gift is alleged to have been confirmed by Bishop William St Calais of

Durham (1080-96) on 27 April 1085. This instrument pretty much

copied the same terms as the previous charter, but added the fact that

his predecessor, Bishop Walcher (1071-81), had confirmed this gift in

his synod and that Count Aubrey Coucy (1080-85/6) had also confirmed

the same in Bishop William's presence. This document was alleged

to have been witnessed by Bishop William, with 7 men recorded as

priests of various places, one man who should probably have been

recorded as a priest and a single cleric. The odd priest out in

this list is Merwin who is described as the priest of Chester (Cestre).

Presumably he was in the entourage of Earl Hugh of Chester (1071-1101)

who held lands in the North, but quite what Merwin was doing in the

Durham chapter is another matter. That this was another Durham

forgery is likely.

Similarly the abstract of charters from the lost Liber Ruber

of Durham probably contained at least some forgeries although much of

it appears based on solid history. It is also interesting in that it

states that the Conqueror burned down Jarrow, no doubt in the Harrying of the North and that King Malcolm III burned Monkwearmouth (Weremouth).

This tends to support the fate of Tynemouth church in 1070. An

abstract of this lost work also mentions the charter recording the gift

of Tynemouth church to the Jarrow monks.

If the rather contradictory accounts of the state of Tynemouth recorded

at Durham are ignored, it is suggested that the church was ruined when

it was given as a daughter house to St Albans abbey by Earl Robert

Mowbray (1086-95). This gift is supposed to have led to the long

and acrimonious dispute with the monks at Durham. The first recorded act in this dispute occurred in 1093.

This Paulus [abbot of St

Albans, d.1093] entered the church of Tynemouth, which they had

possessed against the prohibition of the monks of Durham, through the

violence of Count Robert, and being struck with sickness there, on his

way back, he died in Setterington near York...

Soon after his death on 13 November 1093, the priory became the

apparently brief resting place of yet another king, this one having

been killed on the same day at Alnwick.

But the body of the king [Malcolm],

when there was none of his people left to cover it with earth, two of

the natives laid it in carts and buried it in Tynemouth.

Although Malcolm's body is said to have been later taken to Dunfermline abbey by King Alexander (1107-24), who also granted his protection to the church, his and the bones of Malcolm's son Edward, who died with him at Alnwick,

are said to have been uncovered in the church during 1257. It is

also stated that Robert Mowbray (1086-95) had not only killed Malcolm

when he invaded England, but that Robert had also built Tynemouth

church. The latter is certainly untrue. Matthew Paris

(d.1259) has this to say about the king's body going back to Scotland:

Concerning Robert Mowbray, the founder of Tynemouth.

Because of his royal excellence, he [Robert] caused the body of the slain king [Malcolm] to be honourably buried in the church of Tynemouth, which the same earl had constructed.

The Scots, however, later demanding the body of their king,

were granted and given the body of a certain plebeian man from Seaton

Delaval (Sethtune) and thus the impiety of the Scots was deceived.

Certainly in 1257 two coffins were uncovered, one containing the

remains of a large man, the other of a smaller one. Possibly

these are the 2 well carved stone coffins still found in the modern

room made in the eastern corner of the north aisle. As ever such

suppositions are unprovable.

During the rule of Earl Robert, the priory, or at least its precincts, were still defensible and indeed the writer of the Vita St Oswini explicitly states:

Here [Robert Mowbray] began

the church of the holy king and martyr Oswin of exceptional devotion

and in which his most holy body rested; because it was contained within

the confines of his castle of Tynemouth, he enriched it with a great

deal of lands and estates.

This was shown up in 1095 when, during the reign of William Rufus

(1087-1100), a conspiracy was hatched against the king by Earl Robert

Mowbray of Northumberland, William Eu, Stephen Aumale - the king's

cousin - and many others. However, the plot was frustrated by King William

forming the English army and mounting a campaign in Northumberland

which eventually involved Tynemouth castle. The main events that

involved Tynemouth have been related under Bamburgh and Newcastle,

but for completeness the end of one account more concerned with

Tynemouth is repeated here. The Durham chronicler Simeon notes

that after the siege of Bamburgh had reached a stalemate:

So he [Earl Robert], having become joyful, went out one night with 30 soldiers to accomplish this [retaking Newcastle]. When this was discovered, the knights who guarded the [siege] castle [of Bambrugh] pursued him, communicating his departure by messengers to the keepers of Newcastle.

Which he [Robert], being unaware of, attempted to accomplish what he

had begun on a Sunday. But he could not do this, for he had been

caught.

For this reason he fled to

the monastery of St. Oswin, king and martyr [Tynemouth], where, on the

sixth day of his siege, he was severely wounded in the leg while he was

resisting his adversaries, many of whom were killed and wounded.

Of his own men some were wounded, but all were taken prisoner; but he

fled into the church; from which he was extracted and placed into

custody.

This quite clearly shows - if the recording is correct - that the earl

and his men defended the perimeter of the rock and then fell back on

the church when those defences were penetrated. This implies that

there were defences on the rock capable of being defended for 6

days. Other accounts of the siege are printed under Bamburgh and do not need repeating here, though it should be noted that there has been much confusion over the 2 castles of Newcastle and Tynemouth.

There are several similar contemporary accounts of the action at

Tynemouth which all tell the same story, but the Durham accounts are

undoubtedly the best - even if they are patently biased in favour of

the monks of Durham and their brethren at Jarrow.

There is a second Durham account which mentions the siege, but more

importantly the events before the siege, namely the earl taking

Tynemouth from Durham, giving it St Albans abbey and his alleged reasons for doing so.

Robert Mowbray, fierce in

spirit and vigorous in arms, when the earl was in possession of the

honour [of Northumberland], to the detriment of the honour, he was

driven by hatred against Holy Church. For in the first place he

made as much effort as possible to oppress her with slanders and

insults. No matter how he tried to harass and destroy her rights;

whatever he could do to his enemy he did and he threatened to do more

than he could. And therefore Tynemouth church, that was truly the

right of the church of St Cuthbert, as the whole province knows, became

the first victim of his violence. Hence, in short, those who had

long lived as monks, nay, among the monks, including the saint himself,

were driven out with insults, and it was transferred to the possession

of a certain Abbot Paul, who lived in a distant place. However,

that abbot, lest he should do injury to the purpose and rank of the

church, the monks of Durham by letters of legation through themselves

and by other religious men, warned, implored and forbade him from

receiving such robbery, but they endeavoured to get him to disavow the

grant in vain. He was not swayed by the elegance of anyone, nor

even by the venerable Confessor, nor by the respect for his order,

which forbade him from undertaking robbery; true, but not with

impunity. As for the outcome of the matter stated, each of them,

that is to say, the rapist and the possessor of the rapine, paid the

penalty for their rashness to the avenger. For the abbot, a long

time ago came before the monks, where, once he had seen the church

itself for the first time, was seized with a sudden illness, and he who

had arrived safe and sound was brought home dead. But the earl,

in the intervening time was surrounded by the king's evil followers, so

surrounded in every direction by the advance of the enemy, he could

neither proceed nor retreat, so he entered Tynemouth as a

stronghold. For this place presented itself as inaccessible on

the eastern side and on the northernmost cliff above the ocean and

elsewhere is in a higher position which makes it an easy defence.

He, trusting to this protection and the proven hands of his soldiers,

promised a far different end to what was to come to him and to his

enemies. For two days the siege continued, the enemy, with the

intention of either conquering or falling in the attempt, fighting from

above, attacked with sword and fire. Nor do I mourn; for they

took a difficult, but not too difficult position. For they broke

in without any loss to themselves, cut others down, weakened others by

wounding them, then kidnapped them, dragged them, and forced the earl

himself, wounded and already despairing of what was happening, into the

church. O righteous judgment of God! Behold, as the

scripture sings, "The sinner is caught in the throes of his

acts." And, "He opened the pit and dug him out." And "He

fell into the pit which he made." It is certainly in the same

church that the earl himself was now made a prey to his enemies, as we

have said before in St. Cuthbert's presumption. In the same way,

I say, as the proud man had snatched away from the saint, now the

pitiful man himself is snatched away, dragged, and led to the king,

whose death he was trying to bring about; and to this day he is kept in

the chains of custody.

Robert Mowbray was said to have lived for 30 years as a prisoner and

then as a monk of St Albans, ie to about 1125, so presumably this

account was written before that time. Regardless, it does state

that no attempt was made to defend the church, but all the fighting was

done outside it, presumably along the rock defences, even though they

only lasted 2 days in this account and not 6. The account itself

was recorded to justify the Durham monks reclaiming the church in the

1120s. Again, what is given is a probably partisan account of

events which advances no facts to support their claim to Tynemouth,

merely rhetoric, other than the alleged grant by Earl Waltheof of

Northumberland (1071-76). The claim is expounded in a court case

from 1121.

The monks of Durham brought a

claim concerning the church which is in Tynemouth to the chapter of St

Peter of York in the presence of the aforesaid bishops, Thurstan [of

York, 1114-40], Ranulf of Durham (1099-1128), a man of Sancti Ebroini

and many others; complaining that this was their right from the

concession of Earl Waltheof, when he gave his cousin, that is his

aunt's son, the little child called Morka, to be nursed by them and by

God in the monastery of Jarrow. He [Morka] was thus commended to them in the church of Tynemouth, the monks themselves taking him by boat to Jarrow,

endeavoured to nurture him diligently and to educate him in the service

of God. From this, they say, at the time when our brothers, the

monks of Jarrow, assumed the care of that place [Tynemouth], Edmund and

then Eadred, their monks, served the church themselves, together with

the priest Elwald, who had also been a canon of the church of Durham,

from whence he was wont to go to Durham as often as his duty allowed,

to celebrate mass for the week. They also remembered Wulmarus, a

monk of their congregation, and other brothers in their turn, who were

sent to perform divine services there [in Tynemouth], being sent there

from Jarrow.

The bones of St Oswin also, as it pleased them, their brethren carried

from time to time to Jarrow, and brought them back to their former

place when they pleased. Finally, when Aubrey [Courcy, earl from

1080 to ?1086] had accepted the honour of the earldom, he also gave

them the same place [Tynemouth] when they were transferred to Durham.

Wherefore soon, by the resolution of the whole chapter, their monk

Turchill was sent thither, who, having renewed the church roof, dwelt

there for a long time, until afterwards by Earl Robert Mowbray, because

of the hatred which he had against Bishop William, he would be

violently expelled by the earl's servants, Gumerum and Robert

Taca. Not long after that, Abbot Paul of St Albans monastery

obtained the aforesaid church from the earl, whom he was going to see

when he came to York. Turgot, who then held the priory church of Durham,

sent monks and clerics thither and in the presence of Archbishop Thomas

the Elder, and many persons of great reverence, he forbade him by

canonical authority from usurping the rightful place of the church of Durham,

and thus made him the violator of the sacred canons and fraternal

charity. But he [Paul] unworthily answered that his forbidding

was worth naught. But when he arrived there, he was seized with

sickness and while he was returning, he ended his life in Settrington,

not far from York. Thus [the Durham

chapter] lost the church of Tynemouth [apart from in Wikipedialand

where Turgot's speech was successful].

This complaint was made at York, about the middle of Lent and was repeated a little later in the week of Easter, the fourth of April, in Durham,

before a great assembly of the principal men, who had then, perhaps on

account of some business, flocked thither, namely, Robert Bruce, Alan

Percy, Walter Espec, Forno Fitz Ligulf. Robert Whitwell, Sheriff Odard

of Northumberland, with the elders of the same county and several

others. In the face of these multitudes, when the monks were

pouring out their complaints, behold, Arnold Percy, a man known for his

family and riches, and standing in the truth of what he asserted, rose

up and affirmed in witness of the truth before all, and that he had

heard and seen the earl repent of this injury which he had violently

inflicted on St Cuthbert. He said, "When the earl, being taken

prisoner in the place which he had taken away from St Cuthbert, was

brought to Durham on account of the wounds

which had been inflicted on him, he begged that he might be allowed to

enter the church oratory to pray." When he was not permitted to

by the barons, he broke down in tears, and looking towards the church

with a groan, said, "Oh St Cuthbert, I justly suffer these calamities,

because I have sinned against you and yours. This is your revenge

on the wickedness of my life. I pray thee, saint of God, to have

mercy on me."

Hearing this, they all said that an unjust act had been committed against the church of Durham;

and although the matter could not be rectified at present, yet they

prudently asserted that this slander could be put right at a future

time when there would be many men in attendance to witness it.

The tale told above, full of sound and fury, but no real legal

substance, also contains several contradictions. If Turchill had

renewed the church roof and dwelt there a long time, why was the church

said to have been roofless for 15 years in 1085, ie. since 1070?

What were the real reasons for Earl Robert granting the church to St

Albans? The enmity claimed with William St Calais (1080-96)

probably only really started with the 1095 campaign when the bishop led

troops against Robert. Before that Robert may have sold, possibly

under royal pressure, his authority south of the Tyne and north of the

Tees to Bishop William. Quite certainly the monks of Durham

wanted this story believed in the twelfth century and quite happily

forged a number of charters alleging to concern the founding of the

palatine county of Durham. Quite possibly if the removal of Durham

from the earldom of Northumberland did occur in this way, it may have

led to Mowbray seizing Tynemouth from Durham as it lay north of the

Tyne. Some of the documentation concerning this is referred to in

the lost Liber Rubus of Durham which recorded the concord made between

Bishop William St Calais of Durham and Count Robert of the

Northumberians by William the Conqueror (1066-87). Further, that

this charter of the transaction was likely forged, is proved by the

fact that Bishop William is referred to as the first bishop of that

name. This suggests the charter's provenance no earlier than 1226

when a second William became bishop. A forged charter was also

seen and recorded by Rymer. This records the peace made between

Bishop William St Calais of Durham (1080-96) and Earl Robert of

Northumberland (1086-1095). This is jauntily signed by King William

(1087-1100), Bishop William (d.1096) and Earl Robert in 1100, despite

the fact that one of them was dead and the other imprisoned - indeed

the king himself was killed on 2 August 1100. Perhaps it is best

to say that this charter might contain a later encapsulation of the

original concord between bishop and earl, or with less charity, that it

is simply another Durham forgery and not a very good one at that if the

monks didn't even know the obit of their own bishop. A further

charter of this affair existed in the Durham archives on which Rymer's

charter seems to have been based. It certainly carries the same

core material, but omits the erroneous dating clause. In its

place it has an impossible witness list, one of them being Bishop

Walcher, who died 7 years before the charter could possibly have been

made. As such it seems probable that all these charters

concerning the establishment of the principality of Durham are

forgeries. It therefore also seems inevitable that the events of

1121 as reported by the Durham chronicler are similarly biased.

Judging from the above it seems best to assume that the gift of

Tynemouth to St Albans had only occurred shortly before the earl's

discomfiture as the 2 events and St Cuthbert's vengeance seem so

closely intertwined. Certainly the earl retiring there when he

failed to surprise Newcastle suggests

that he was hopeful of a positive welcome and had some confidence in

the place's defensive strength. Such confidence would not have

been likely to be placed in any Durham monks. Certainly by the

twelfth century they were obviously hostile to him and his memory,

especially as they [or at least Simeon] claimed that the problems were

‘because of the hatred which he had against Bishop William' St

Calais of Durham (1080-96). In 1083 the bishop had transferred

the reformed brethren of Jarrow and Monkwearmouth to Durham

to make a new chapter after he expelled the married clergy from his

cathedral. Possibly this is when Earl Robert transferred the

allegedly neglected Tynemouth priory to St Albans and when the Tyne was

established as the border between the counties of Durham and

Northumberland. Simeon's account suggests that Robert's

ministers, Gumer and Robert Taca, only expelled Turchil from Tynemouth

due to his hatred of Bishop William, which would point towards the

event happening near to 1095, but this woud make a nonsense of Abbot

Paul arriving at Tynemouth in 1093 before Turchil had been

expelled. Probably the most likely time for the introduction of

the St Albans' monks into Tynemouth is around 31 December 1091.

After King Malcolm III paid homage to King William Rufus, it is recorded in a St Albans' chronicle that:

At this end of this year and

the beginning of the next, both being contiguous, the church of St

Oswin of Tynemouth was established and formed by the monks according to

the regular rule of Saint Benedict, under Abbot Paul of St Albans.

This is not contradicted by the more detailed account of the affair

kept at St Albans, except in so far as they added the dead Archbishop

Lanfranc into agreeing the gift as translated below.

Considering all these contradictions and downright forgeries, it is

worth spending some time examining the career of Abbot Paul of St

Albans (1077-93). He was a kinsman and it was thought even the

son of Archbishop Lanfranc (1070-89). He first came to notice in

1077 when Lanfranc made him abbot of St Albans on 28 June, after the

abbey's lands had been wasted by the king. As abbot he undertook

the rebuilding of the church and undertook the monastic reform demanded

by Lanfranc. This became the pattern for reform in all the

Benedictine houses in England. He also set St Albans apart by

rebuilding the scriptorum and causing many books to be copied there by

well supported scribes. He also personally acquired some 23 fine

vellum volumes as well as psalters and service books for the abbey

library. As a consequence of his works, his church received many

gifts from admirers of his reform. Further, Abbot Paul was known

to be contemptuous of the English monks who he regarded as unworthy,

lazy and ignorant. He was also horrified that some were totally

illiterate.

On some of the new lands granted him, Paul founded reformed cells as

advised by Lanfranc. These were ruled over by priors sent from St

Albans. Such places were founded at Belvoir in Lincolnshire,

Binham in Norfolk, Hertford, Wallingford in Berkshire and of course,

Tynemouth. Sadly the record concerning Tynemouth is not very

informative.

This Note Concerning the Cell of Tynemouth

At the same time [during the same abbacy, 1077-93], Robert

Mowbray, an illustrious man, an earl, that is to say, of the

Northumbrians, having been made certain of the religion of the church

of St Albans by Abbot Paul, caused the monks of the church of St Albans

to be placed in the church of St Mary of Tynemouth, in which the body

of the Blessed Oswin, king and martyr, rests; and it, with all its

appurtenances, was established by the benevolence of the king and

Archbishop Lanfranc [1070-89] to be the cell of St Albans.

This adds little to the story, other than the fact that Earl Robert

granted Tynemouth to St Albans for it to be reformed in the new manner

- not out of hatred for Bishop William St Calais. Further, the St

Alan's work mentions nothing of the manner or place of Abbot Paul's

death. It would appear that the monks of Durham were not being

totally honest in their entreaties, relying on bluster and forgeries,

rather than honesty and facts.

Despite the Durham monks' protestations, Tynemouth priory remained with

the monks of St Albans. One of the major reasons for this were

the actions of King William Rufus (1087-1100). When he was besieging Newcastle upon Tyne

in the Spring of 1095, the king passed 3 notifications in favour of

Tynemouth and St Albans. In the first he confirmed to St Mary and

St Oswin and the monks of Tynemouth their court with sac and soc, toll

and team and infangthief and wreck and with all the customs belonging

to himself. In the second he informed Bishop William St Calais of

Durham, Robert Picot and all the barons of Northumberland of the same

thing. Finally and presumably at the same time as this document

was witnessed by Eudo Dapifer (d.1120) who had witnessed the previous 2

notifications which were recorded as being made during the siege of Newcastle,

he notified Archbishop Thomas of York and Bishop William of Durham that

he had granted to St Albans the church of Tynemouth with its

appurtenances both north and south of the Tyne, together with all the

gifts made by Earl Robert of Northumberland and his men before the earl

had incurred forfeiture. This last document was also witnessed by

Peter Valognes (d.1109+, Eudo's brother in law) and all 3 were copied

into the chartulary of St Albans abbey. Funnily enough they do

not appear in the Durham account!

With the fall of Earl Robert in 1095, Northumberland had escheated to the Crown. It was therefore either Rufus or more likely King Henry I

(1100-35), who granted various Northern vills to Tynemouth. These

were recorded as being given to the priory during the time of Abbot

Richard of St Albans (1097-1119) and consisted of Monkseaton (Settona), Whitley Bay (Witeleia), North Shields (Sehihala), Stanton (Stantona), Old Bewick (Bewik), Lulburn (Lilleburna), Eglingham (Egulvingham), North Charlton (Chertona), Earsdon (Ardesdona) and Coquet Island. Around the same time it was decided that the revenue from Amble, Coquet Island and the churches of Bywel

and Woodhorn should go directly to St Albans. Of these lands, of

which not all are mentioned in the St Albans' list above, Tynemouth,

Preston, Amble and Hauxley seem to have been granted by Mowbray

himself. Queen Matilda (1100-18) granted Bewick, Lilburn,

Harehope and Wooperton around 1105/06 and Henry I

Whitley Bay, Monkseaton and Seghill in the period after that, but

before 1116. Possibly this royal grant took place in 1110 when St

Oswin was translated from Jarrow to Tynemouth. King Henry

(1100-35) certainly confirmed Tynemouth to the abbot of St Albans with

all its tithes in Northumberland which Earl Robert and his men had

granted them, namely the tithes of Amble, Bothal, Callerton, Corbridge, Disington, Elswick, Newburn, Ovington, Rotherbury, Warkworth

and Wooler. The rest of the priory lands, Backworth, Bebside,

Chirton, Cowpen, Denton, Earsdon, Flatworth, Murton, Welton, Westgate,

West Hartford, Wolsington and Wylam were acquired from lesser men or

from persons unknown, although some were men of the earldom like Guy

Balliol (d.1112/30), Robert Bruce (d.1142) and Gospatric

(d.1138). There were also a variety of rents, some of which were

lost to other institutions, namely St Albans, Durham and the

archbishopric of York.

It was probably in the first half of the reign of Henry I

(1100-35), that Abbot Richard Aubigny of St Albans (1097-1119), with

the unanimous consent of his monks, decreed that Tynemouth priory

should annually pay St Albans 30s and be free of all other demands,

with the abbot keeping in his own hands Amble, Coquet Island and the

churches of Bywell

and Woodhorn. Further the Tynemouth monks were to support him and

up to 20 attendants when they came to the priory for 15 days, unless

the visit were in support of the priory in which case Tynemouth was to

pay his expenses. At the end of September 1111, a workman fell

twice while working on the roofs of the church and dormitory, once some

19', but the worst ill effects he suffered was a sprained ankle.

In 1121, when Geoffrey Gorron was abbot of St Albans (1119-46), the

monks of Durham made an ineffectual attempt to regain the monastery,

based mainly on the hearsay that Earl Mowbray had repented of his gift

after his capture. This has been commented upon above.

Northumberland passed under Scottish control in the late 1130s. An initial attack by the Scots in 1136 was halted by King Stephen at Durham.

Around this time he may have issued a charter granting that Tynemouth

and its lands were to be free of all castle works in

Northumberland. It was possibly also at this time that the king,

from York, granted Prior Richard Tewyng of

Tynemouth, for the reestablishment of his priory, which had been

overthrown and wasted by the frequent attacks of the Scots, were to be

able use their liberties to this effect. Earl Henry of

Northumberland (1138-51), later confirmed the grant of freedom from

castle works.

In January 1138 William Fitz Duncan [Skipton] invaded Northumberland for King David

(1124-53), who followed him soon after and forced Tynemouth priory to

pay 27m (£18) for his protection. During this time the

value of the church increased significantly from the pilgrim trade as

well as by revenue from the lands that appertained to the priory.

These included Benwell, Coquet Island (which may have been granted by

Mowbray, ie before 1095), Earsdon, Monkseaton, North Shields, Whitley

Bay, Woodhorn, Woolsington and Wylam, as well as tithes from Corbridge, Newburn, Rothbury, Warkworth and Wooler.

In 1147 Earl Henry of Northumberland (d.1152) exempted the monks of

Tynemouth from contributing to castle works at Newcastle and all other

castles in his earldom. Then, in 1156, Northumberland was

reclaimed from the Scots by King Henry II

(1154-89). That king subsequently made a charter to Tynemouth

restoring and confirming the monastery lands which he had seized on

account of the flight of Adgar into Scotland and the war against the

king of Scots. The lands held by Adgar were Eglingham, Bewick

and Lilburn, all held by him from the priory and found by inquisition

to be the prior's. It is not certain if this refers to the

reclamation of Northumberland in 1157 or the Young King's War of

1173-74.

Despite all of these disturbances, no attempt seems to have been made

to reclaim Tynemouth by Durham until the 1170s. The resulting

case was heard before Bishop Bartholomew of Exeter (1161-85) during the

pontificate of Pope Alexander III (1159-81). Here the causes of

the old case were repeated by the prior of Durham, backed by what he

claimed were 2 authentic documents. The first was the charter

claimed to have been made by Earl Waltheof confirming Tynemouth to

Durham ‘with everything which it possessed at the time when the

confirmation was made or which it might possess hereafter'. This

was claimed to have been made in the presence of Bishop Walcher who

‘condemned by a perpetual anathema those person who, at any time

whatsoever, should presume to alienate the church of Tynemouth from the

church of Durham'. The second document was the charter of Bishop

William St Calais which was similar in outlook to the confirmation of

Bishop Walcher. It should be pointed out that both charters were

just what the priory needed to substantiate its claim and how

‘lucky' it was to have just 2 such charters surviving.

The prior, claiming that these documents were sufficient to win him his

case, then brought forward various ancient clerks and laymen who lay

witness to Tynemouth having belonged to Durham

before they were expelled violently by the lay power and the monks of

St Albans' intruded into their church. The prior also stated that

as these men were very old and now infirm it would be difficult to make

them come forth and repeat these claims a second time without risking

their lives. Considering that the church had been lost to Durham

around 1091 and they were discussing events happening as early as the

1060s these men in the 1170s must have been very old indeed!

After the prior had presented his case, various monks and clerks from

St Albans came forth and presented letters to the effect that their

abbot was detained in the South by illness. The prior spoke out

against this and demanded justice as both sides had had 6 months to

prepare. The judges then decided to refer the case to the pope,

which brought proceedings to an end.

The pope returned proceedings back to England where 3 judges, the prime

of whom was Bishop Roger of Worcester (1164-79), determined the case on

12 November 1174. There the case was brought to a conclusion by

the application of a compromise. Under this Bishop Hugh Pudsey of

Durham (1153-97), his prior and the whole Durham convent confirmed

Tynemouth with all its appurtenances to St Albans abbey. In

return the abbot of St Albans gave to them Bywell

and Edlingham churches with all their appurtenances after the deaths of

the serving religious there. To confirm the exchange the monks of

St Albans handed over their muniments for the 2 churches and the prior

his for Tynemouth excepting those where the church of Tynemouth had

been confirmed to Durham along with its other possessions which were

not a party to the dispute. With this the Durham monks' vexatious

claim to Tynemouth was allowed to lapse.

It was probably in 1204 when the monks of Tynemouth paid 50m (£33 6s 8d) for a confirmation of their charter and for King John to confirm them in their possessions. These now consisted of Amble, Backworth, Bebside, Bewick, Carlbury (Carleberry), Chirton, Cowpen (Copun), Denum, Dissington [n'r Dalton], Eglingham, Elswick, Darsdon (Erdesdon), Hauxley (Hawkeslaw), Henshaw? (Helleshaw), Lilburn (Lillburne), Millington, Morton in the bishoprick, Morton, Preston, Rayless (Royley), Seaton, Seghill, Ulsington, Whalton? (Weltedon), Whitley Bay and Wylam with the churches of Tynemouth, Bewick, Bolam (Bolum), Coniscliffe (Connyscliff), Eglingham, East Hartford (Hereford) on Blyth, Hartburn (Hertburne), Whalton and Woodhorn, together with the tithes of Corbridge, Hartlepool (Hertness), Middleton on Tees, Newburn, Rothbury, Warkworth and Wooler.

Possibly during the late twelfth century an exile wrote back to St

Albans about his enforced stay at the newly completed church of

Tynemouth. His letter, a copy of it found in a St Albans'

formulary of the fifteenth century, is precised below:

Our house is confined to the

top of a high rock, and is surrounded by the sea on every side but

one. Here is the approach to the monastery through a gate cut out

of the rock, so narrow that a cart can hardly pass through. Day

and night the waves break and roar and undermine the cliff. Thick

sea-frets roll in, wrapping everything in gloom. Dim eyes, hoarse

voices, sore throats are the consequence. Spring and summer never

come here. The north wind is always blowing, and brings with it

cold and snow; or storms in which the wind tosses the salt sea foam in

masses over our buildings and rains it down within the castle (in

castrum). Shipwrecks are frequent. It is a great pity to

see the numbed crew, whom no power on earth can save, whose vessel,

mast swaying and timbers parted, rushes upon rock or reef. No

ring-dove or nightingale is here, only grey birds which nest in the

rocks and greedily prey upon the drowned, whose screaming cry is a

token of the coming storm. The people who live by the sea-shore

feed upon black malodorous sea-weed, called 'slauk', which they gather

on the rocks. The constant eating of it turns their complexions

black. Men, women and children are as dark as Africans or the

swarthiest Jews. In the spring the sea air blights the blossoms

of the stunted fruit trees so that you will think yourself lucky to

find a wizened apple, though it will set your teeth on edge should you

try to eat it. See to it, dear brother, that you do not come to

so comfortless a place.

But the church is of wondrous beauty. It has been

lately completed. Within it rests the body of the blessed martyr

Oswin in a silver shrine, magnificently embellished with gold and

jewels. He protects the murderers, thieves, and seditious persons

who fly to him, and commutes their punishment to exile. He heals

those whom no physician can cure. The martyr's protection and the

church's beauty furnish us with a bond of unity. We are well off

for food, thanks to the abundant supply of fish, of which we tire.

In 1248 the body of Earl Patrick of Dunbar, a descendant of Earl

Gospatric of Northumberland (d.1074), was brought back from his place

of death, Marseilles in France, and buried in the priory. The

castle doesn't seem to have seen action in the Baron's War, but it did

offer refuge to skilled workers. At some time towards the end of

the war a canon of Hexham wrote to the cellarer of Tynemouth stating:

I am sending you Stephen Len,

who is an honest workman and, as I have heard, is skilled in plumbing

and in laying on water. Do not think the worse of him for his

shabby clothes. He has 2 or 3 times lost his all in this war,

which is hardly yet over.

On 13 December 1264, when Simon Montfort (d.1265) was running England,

Abbot Norton of St Alban's made his visitation of Tynemouth. He

met 6 men who owed him military service and received their

homage. He then spent the rest of the month travelling the

priory's domains and taking the fealty of those men who owed it to

Tynemouth. Sometime soon after the 4 August 1265 battle of

Evesham, Sheriff John Halton, wrote to the prior of Tynemouth informing

him that John Vescy (d.1289) had fled the battle and was planning to

cross the Tyne from South Shields so the prior was to guard the ferry

and stop Vescy crossing on pain of royal displeasure. Whatever

the prior did Vescy got through with his treasure, a foot of the

recently killed Simon Montfort, to Alnwick castle.

In 1292 there were disputes between the citizens of Newcastle and the

prior, who had built a quay at North Shields, but was obliged by act of

parliament to destroy it after the men of Newcastle had already laid it

waste and beat the monks they found there. The same year the king

claimed the priory as a royal advowson against the abbot of St

Albans. The abbot, ‘knowing that he could not stand against

the royal power of the plea' threw himself on the king's grace, which

course of action caused the king, under peer pressure, to grant away

his perceived right to the advowson to St Albans. The story is

taken up by the St Albans' chronicler.

In the fifth year of the

abbacy of Abbot John (1290-1301), a rumour was brought to him that the

prior of Tynemouth, who was then called Adam Tewing, was plotting a new

and unusual thing there and, among other things, he was preparing to

resist and rebel against his abbot. The abbot, however, soon

having the matter related as if he had discovered it, as it was easy

for him to believe that he had, immediately, as secretly as he could,

set out for Northumberland; and, arriving at Newcastle,

arranged with the mayor of the said town to bring him to Tynemouth with

a multitude of armed men, secretly and by night; lest the prior should

be invulnerable during the said tumultuousness.

But this thing could not be accomplished, or at least not

accomplished, without the connivance of a certain citizen of Newcastle,

whose name was Henry Scotus. He had been one of the prior's

household and he was esteemed and accepted by all the familiars in the

castle on account of the love between the prior and himself.

Henry, however, being moved by his conversation with the abbot, as soon

as he learned that the abbot would reward him very richly if he

betrayed the prior, his friend; he agreed to do the deed and, setting

out with the abbot, he arrived in silence at the gates of Tynemouth

castle; and having summoned the porter, asked for it to be opened for

him. He [the porter], however, suspecting nothing wrong with him

[Henry], whom he believed to be his master's friend, opened the door

without hesitation.

And lo! suddenly the abbot

rushed in with the crowd which the mayor of Newcastle had gathered and

seized the keys, handing them over to a certain squire who had come

with him, entrusting the guard of the gate to him. Then he [the

abbot] went to the door of the prior's chamber and suddenly knocked,

wanting to have it opened for him. But the former [the prior] had

just come from Matins and, having only put down his hood, was resting

on the blanket on the bed. When he heard the sound of knocking he

inquired who was outside. At once the answer was that it was the

abbot; "Away", said he, "for what would the abbot be doing this

way?" And immediately they rushed into the chamber along with the

abbot and put the said prior in custody, by order of the abbot; after

which in a few days the abbot crossed the sea to the monastery and

installed a new prior in the same cell [Tynemouth]. And he

rewarded the said Henry Scotus lavishly as a reward for his treachery,

giving to him and his heirs, who were legitimately begotten of him,

many lands and liberties in the town of Elswick (Estwik), to the

detriment of the said cell.

It was reported that the

aforesaid Prior Adam of Tynemouth and John Throklow, with some others

of the assembly there, had procured that plea which the king moved

against the abbot on the advowson of Tynemouth priory; so that, when

the abbot was excluded from the right of advocacy and the king was

introduced, he could more freely make his complaints to the king, who

had been their advocate against the abbot... the sudden capture,

and the removal of the said John Thorlow and his accomplices from the

said cell, quite despicably; who, shackled and bound by the bonds of

art, were sent to the monastery [of St Albans].

As it turned out, this was just a minor inconvenience compared to what

was about to happen to Tynemouth. In 1296 the Scots raided as far

south as Hexham which was sacked before the battle of Dunbar brought

the war pretty much to end on 27 April. After the successful

campaign the king, who had by then retired from a subjugated Scotland

to Berwick on Tweed, granted the prior and

convent of Tynemouth a royal licence to crenellate their priory on 5

September 1296. The full text in the pipe roll reads:

For the prior and convent of

Tynemouth. The king sends greetings to all. Know that we

have granted for ourselves and our heirs, to our beloved in Christ

prior and convent of Tynemouth that they themselves may strengthen and

crenellate their aforesaid priory with a wall of rock and stone, and

that they may hold it thus fortified and crenellated to themselves and

their successors without risk or hindrance from us or our heirs or our

justices, or our other bailiffs, or our ministers, or whomsoever.

The earlier descriptions of the site make no doubt that the site was

already a castle before this grant was made. Indeed, it is

specifically mentioned as a stronghold or castle from 1095.

Formally fortified monasteries are rare, certainly compared to normal

castles or religious houses, although churches were often put in a

state of defence when necessary - usually in cases of the utmost

necessity, viz. Wherwell abbey in 1140, Hereford cathedral in

1138. The most obvious examples of fortified priories are to be

found in frontier areas like Kells in Meath, Ireland, Ewenny in

Glamorgan, Wales and Loarre in Castile, Spain. Most

‘fortified churches' in the West hardly count as castles,

especially when compared with the 3 places mentioned above. Most

claimed ‘fortified churches' are pretty pathetic as military

structures, viz. in Ireland the churches of Clonmel, Tiperary;

Hospital, Limerick; Newcastle, County Dublin; Taghmon, Westmeath.

In Portugal there are Coimbra, Guarda and Lisbon, with Flor de Rosa

being a notable exception in being better fortified. Along the

Scottish border with England a few churches like Boltongate, Burgh by Sands,

Great Salkeld and Newton Arlosh are described as defensive and the same

has been claimed of Garway church in Herefordshire. Mostly these

are simply battlemented churches and the battlements probably are of no

great antiquity. Further the claimed thickness of the walls may

have more to do with sustainability of the building, rather than

defensive measures.

King Edward I (1272-1307)

obviously liked Tynemouth, returning there and staying in early

December 1298 and 1299 and finally for a week at the end of June 1301

when the king confirmed the charters of St Albans. His new wife

obviously liked the place too for she stayed there from June to October

1303. The king's final visit was for nearly a fortnight in mid

September 1304, when, with the queen's meditation, Tynemouth fair was

restored to the priors for a full fortnight from his feast day.

Tynemouth's next foray into historical literature occurred during the

ongoing war against the Scots. Around Christmas 1311, the king's

favourite, Piers Gaveston, had returned from exile into the North of

England where he met Edward II (1307-27). Gaveston's return had provoked a baronial uprising and on 4 May 1312, Gaveston and Edward II were surprised by baronial forces at Newcastle on Tyne,

causing the pair to flee to Tynemouth. There they left the queen

and took ship in stormy seas, despite the queen's pleas not to be

abandoned, to Scarborough. The

rebels had no interest in besieging the queen in Tynemouth, where in

1322 she claimed to have been left in mortal danger, and instead set

off to Scarborough after the king and his hated favourite. The story is succinctly told in a royal writ:

Memorandum that Edmund Malo Lacu, seneschal of the lord king's hospital..., before nine o'clock at Newcastle upon Tyne,

on Thursday in the feast of the Ascension of the Lord, in the fifth

year of the king's reign, brought with him the great royal seal, under

the seal of the lords, Adam Osgodeby, Robert Bardelby & William

Ayrmyun, to the king himself at Tynemouth. On the same day, after

midday, Earl Thomas Lancaster came to Newcastle

town with Henry Percy, Robert Clifford and many others with horses and

arms and their retinue; they entered the said town, and stayed there

for 4 days. And the lord the king, on the morrow of the said day

of the Ascension, departed from Tynemouth, and went by boat to Scarborough.

Presumably the king felt the rebels had no intention to pursue the

queen. In this assumption the king proved correct. This

seems more likely than Lancaster baulking at the defences of Tynemouth

castle.

It was soon after this that the castle was put to the test. In

November 1313 the government found it necessary to issue letters of

protection to Prior Robert Norton of Tynemouth against the Scots.

Subsequent to the English defeat at Bannockburn in June 1314, King Robert Bruce (1306-29) attacked Tynemouth, but failed to take the castle, making the place one of the few safe places in the North.

The Scots, meanwhile, engaged in slaughter and plunder throughout Northumbria and the western parts from Carlisle to York,

without any hindrance, and ravaged everything that came in their way

with sword and flame. And it must be known that no place remained

in those parts where the English could safely retreat, except for the

city of Carlisle, and the town of Newcastle on Tyne

and Tynemouth priory and the rest of the castles throughout

Northumbria, which were guarded with tiresome labour and immense

expense.

On 15 September the king issued from York another protection for Tynemouth priory as:

the king wishing to provide

for their security, whose goods and chattels are frequently wasted by

the inroads of the Scots in the county of Northumberland. Nothing

is to be taken of their corn, hay, victuals, carriages or other goods

or chattels for the king's use against their will.

Prior Robert Norton died about this time and was replaced by Richard Tewing who:

well and nobly ruled the cell

with a strong hand in a time of great distress, when for 4 years on end

no serf dared plough and no sower dared sow for fear of the

enemy. Yet nonetheless did he keep the place and not only by his

industry did he honourably maintain the monks, but during that time he

kept within the priory 80 armed men to guard the place, not without

great expense.

In 1317 a local revolt led by Gilbert Middleton, who was occupying Mitford castle, led to the fortress being used as a prison, until the rebel was subsequently caught and executed.

Of a certain treacherous soldier, Gilbert Middleton

Meanwhile it happened that the aforesaid Gilbert Middleton,

after many insults and grievances had often been inflicted by him and

his accomplices on his neighbours and also on the priory of Tynemouth,

when he kept many of his convicted prisoners in the said castle until

they paid a heavy ransom; some noblemen of the country, enduring these

detentions with difficulty and fearing that a similar injury would be

done to them, as if for the deliverance of their own they approached

him under the promise of safety; and, after many words and taunts on

both sides, having set a certain price for them, they then set some

free and handed over some as hostages until the full payment of the

money was made.

With Middleton's removal from the scene the king, with the consent of

the abbot of St Albans, ordered Tyenmouth castle to be handed over to

the custody of John Hausted, to hold at royal pleasure.

Concerning the commitment of the custody of Tynemouth priory.

The king, with the consent of the abbot of St Albans,

entrusts to John Hausted to remain in charge of Tynemouth priory, which

is the cell of the aforesaid abbey, to be held as long as it pleases

the king, for the repulse of the Scots, the king's enemies and rebels,

and for the more secure salvation of the king's people.

Around this time Earl Robert Umfraville of Angus (d.1325) threatened

Prior Richard of Tynemouth with making an example of him as a truce

breaker, unless he handed back 3 ‘poor Scottish boys' who had

came ashore at Tynemouth and been arrested.

In 1321 Walter Selby surrendered at Mitford

with William, the brother of the executed Gilbert Middleton.

Middleton then escaped from Newcastle prison and took refuge in

Tynemouth liberty where a special mandate of the king was required to

finally make the prior surrender him to royal authority on 5 July

1322. The same year, in the aftermath of Edward II's

abortive Scottish campaign, the king's illegitimate son, Adam Fitz Roy

died on 18 September 1322. He was subsequently buried at

Tynemouth priory on 30 September with his father paying for a silk

cloth with gold thread to be placed over his body. Possibly he

had been stationed there with his mother where the king ordered that

she be supported by all the constables of all the castles in the East

March while he himself raised troops and troops were sent to her

aid. In the meantime the queen fortified Tynemouth castle and

then sailed down the coast to safety. Probably immediately after

this on 18 October 1322, Earl David Strathbogie of Atholl (d.1326),

acting for the king, demanded the prior surrender 41 of his armed men

from Tynemouth at Newcastle.

Presumably the earl wished to use them to secure the county against the

Scots. The prior obviously refused this demand and wrote to the

king who on 30 December replied:

To the prior of

Tynemouth. Order to cause a sufficient garrison of fencible men,

both men-at-arms and footmen, to be retained in the priory for the

protection thereof, not permitting the garrison to leave the priory or

any of them to go outside the same, as the prior has the keeping of the

priory at his peril.

To earl David Strathbogie of Athol (d.1326). Order not

to cause any of the garrison of the aforesaid priory to come before him

outside the priory by reason of his appointment to array all the

fencible horsemen and footmen in Northumberland between 16 and 60 years

of age, and to permit the prior and others of the garrison to leave the

priory to make provision of victuals and other necessaries and to

return to the same without molestation, and to counsel and aid the

prior in keeping the priory.

To the sheriff of Northumberland. Order not to molest

the prior and garrison aforesaid by virtue of the order of the said

David to take the prior and others of the garrison and to arrest the

prior's liberty and lands and goods and the lands and goods of the

others, as the king learns from the prior that David has given the

sheriff orders to this effect without expressing any reason for the

same; taking from the prior and the others security to answer to the

king if the said David or others will speak against them in the king's

name for any disobedience in this behalf.

However, the truce made with the Scots did help matters, for now the

prior's neighbours turned upon him and inflicted losses claimed at many

hundreds of pounds. Despite these problems the prior had the

monks' dwellings slated over in 1320 and had a new Lady Chapel built by

1336. The building works probably gives the lie to the prior's

claim to the new King Edward III

(1327-77), that he needed assistance in keeping his soldiers fed, and

unless he received royal aid ‘he must abandon the defence'.

As a result of his plea on 28 September 1327, the government ordered

its receiver of royal victuals at Newcastle

to send to the prior ‘victuals to the value of £20 in aid

of keeping the priory aforesaid against the attacks of the Scotch

rebels as the king has granted this... for his costs and expenses about

the custody of the priory'.

In 1346 King David II of

Scotland (1329-71), invaded Northumberland which caused Prior Thomas de

la Mare of Tynemouth to garrison and supply his priory against

attack. The Scottish commander, William Douglas (d.1353), sent an

arrogant and defiant note to Tynemouth demanding they be ready to get

his supper in 2 days, but he was soon captured at the battle of

Neville's Cross and brought a prisoner into Tynemouth. There the

prior served him his supper, much to his chagrin. At this time

Walsingham claimed that Ralph Neville (d.1367), the custodian of the

Scottish March, was sending Scotsmen to Tynemouth castle on the grounds

that it was a royal fortress and he needed it to contain his Scottish

prisoners. As a result Prior Thomas had to go to the royal court

at Langley and prove that the castle was not a royal fortress and in so

doing retain possession. After this the prior spent £70 on

moving and improving the shrine of St Oswin as well as works on the

priory which included £90 on new brattishing (bracinae) around the dormitory and £80 on other works. There then followed a period of relative peace for Tynemouth.

In the 1380s war was resumed with Scotland and ‘the poor

chaplains, prior and convent of Tynemouth' found themselves constrained

to inform the king:

that whereas their said

priory has been long time and still is one of the strong fortresses of

the North, and now by the inroad of the sea, the walls of the said

priory are in great part fallen, and the rents of the said priory are

in no way sufficient to repair them as well as to bear their other

charges, because great part of their said rents lies near the march of

Scotland and is destroyed by the enemy, therefore the said prior and

convent pray our lord the king and his council to assign them some

reasonable aid, whereby they pray to be recovered, to the saving of the

said priory and fortress and of the country round about.

The result was the king, on 20 February 1380, granting them the right

to acquire lands and tenements amounting to £20 yearly

rent. This would hardly be sufficient for the repairs the castle

seemed to be in need of and the amount of money that was eventually

assigned to the job.

In 1384 the prior complained again that the sea walls and the priory

buildings were in decay and that they suffered a ‘constant mortal

pestilence' of Scottish invasions. In 1389 a Scottish army

reached the Tyne and eventually appeared under the castle walls and

asked to parley. The cellarer went out to speak with them, but in

the meantime the Scottish host began to fire the town.

Consequently a soldier of the garrison shot a sergeant of the earl of

Moray. In the ensuing uproar the cellerar was almost killed, but

he managed to regain the castle stating that he would heal the fellow

and return him to Scotland at his own expense. In light of this

attack and the prior's petition for aid, which was supported by the

dukes of Lancaster and Gloucester as well as the earls of Huntingdon

and Northumberland, the king assigned £500 to the prior on 23

February 1390. The full royal text ran:

For the prior and convent of Tynemouth; greetings to all from the king.

The abbot and convent of the abbey of St Albans, beloved of

us in Christ, besought us that, with the priory of Tynemouth in the

county of Northumberland, a cell of the same abbey, which is situated

above the sea port and the mouth of the River Tyne, has sustained such

and excessive destruction of its lands and possessions by our

adversaries the Scots, that the great tower and the gate and the

greater part of the walls of the said priory, facing the sea, are

prostrated to the ground by such misfortune; considering that all the

goods of the abbey and their priory are not sufficient for the

reparation of the same priory, which used to exist as a fortress and a

refuge for the whole country in time of war... we would like,

considering the damage and loss to the premises of the whole country

aforesaid if the said castle should be taken by our enemies for want of

speedy reparation, which is far off, that the aforesaid abbot, prior,

and convent, unless they have great help and succour from us in this

matter, are unable to defend and repair the same priory itself a

castle, ...to order that the same priory or castle to which the abbot,

the prior, and the assembly, as they asserted, will gradually apply

their full power to do the same, and it will be repaired with all

possible haste. We, having due regard to the aforesaid petition

and other considerations, first for the honour of God and subsequently

at the request of our dearest uncles the dukes of Lancaster and

Gloucester and our dearest brother the earl of Huntingdon and to our

dear kinsman the earl of Northumberland, by our special grace have

granted to the same abbot, prior, and convent to have £500 by a

sufficient assignment to be paid within the next 2 years in aid of the

repair of the aforesaid priory.

The grant was summarised in Walsingham thus:

The Subsidising of Tynemouth

At the same time, the king, through the solicitous mediation

of the dukes of Lancaster and Gloucester, as well as the earl of

Northumberland, and with the help of the counsel of the venerable

father Lord Abbot Thomas of St Albans, granted as much as possible, as