Urquhart Castle

Urquhart

castle, dating from the sixth century to the seventeenth, stands beside Loch

Ness in the Highlands of Scotland, guarding the fertile Glen Urquhart,

13 miles south-west of Inverness.

Urquhart

castle, dating from the sixth century to the seventeenth, stands beside Loch

Ness in the Highlands of Scotland, guarding the fertile Glen Urquhart,

13 miles south-west of Inverness.

History

The meaning of Urquhart is now lost, although exotic guesses can be

found. Excavation uncovered pieces of vitrified stone, which had

been subjected to intense heat that were found in the early twentieth

century to be characteristic of prehistoric or early medieval

fortification. Speculation that Urquhart may have been the

fortress of Bridei son of Maelchon, king of the northern Picts, led to

excavations at the castle in 1983. Adomnán's Life of

Columba records that St. Columba visited Bridei some time between 562

and 586 and that during the visit Columba converted various heathens,

including a Pictish nobleman named Emchath, who was on his deathbed, at

a place called Airdchartdan. Rather than the Wikipedian guesswork

of this being an unnatural mixture of Welsh and Gaelic more

likely it means Urquhart fort, dan being a corruption of dun. The

excavations, supported by radiocarbon dating, indicated that the rocky

knoll at the southwest corner of the castle had been the site of a fort

between the fifth and eleventh century.

The findings led Professor Alcock to conclude that Urquhart is most

likely to have been the site of Emchath's residence, rather than that

of Bridei who is more likely to have been based at Inverness. In

short this gives the ‘castle' an occupation date of the sixth to the eighteenth century.

After the revolt of the MacWilliams - descendants of King Malcolm III

(d.1093) - was put down in 1229, King Alexander II granted Urquhart to

his Hostarius (usher or

door-ward), Thomas Lundin. On Lundin's death a few years later,

the land passed to his son Alan Durward (d.1268). It is considered likely

that the current castle was built around this time, but it is a very

different design to Durward's known castle of Coull - 27 miles west of

Aberdeen and just 10 miles south of Kildrummy. Coull was a standard thirteenth century castle like Kildrummy, Inverlochy, Bothwell

etc, but it was abandoned after its destruction by Robert Bruce in

1307/8. The difference between Urquhart and the other thirteenth century castles could not be more glaring.

Alan Durward was an interesting character. Before his death in

1268 he had become justiciar of Scotland as well as earl of

Atholl. His father had been known as Thomas Ostiarius and was a

benefactor to the monks of Arbroath as well as a signatory to at least

one charter of King Alexander II around 1232. Alan made his first

appearance as Alan Ostiarius domini Regis Scocie, Comes Atholie

in a charter confirmed by Alexander II at Kintore on 12 October

1233. In 1244 he was the first noble to pledge himself for the

fidelity of Alexander II in this king's oath to King Henry III

(1216-72); and further on in the same document undertakes, along with

the seven earls of Scotland, to withstand their own sovereign should he

attempt to play the king of England false. On Alexander II's

death on 8 July 1249, he was one of the chief leaders of the English

party at the Scottish court. The little king's coronation had

been fixed for 13 July, when Alan Dorwart totius nunc Scociæ justitiarus

put forward a claim to defer the coronation till the young Alexander

had been made a knight, but the proposal was refused.

At Christmas 1251, King Alexander III met Henry III at York and was

knighted by him before marrying his eldest daughter Margaret.

While at York Durward's enemies accused him of treason as he had

written to the pope begging him to legitimatise his daughters by his

wife, the natural daughter of Alexander II. This act was thought

to be an attempt to place himself in the succession to the

throne. Although he returned to Scotland as one of the heads of

the English faction, or 'the king's friends' as they were later called,

he soon decided to take refuge in England receiving a safe conduct from

King Henry III in July and being granted licence to hunt in Galtres forest,

Yorkshire, on 22 October 1252. His leading associates were Earl

Malise of Strathearn (d.1271), Earl Patrick of Dunbar (d.1308), and Earl Robert Bruce of Carrick (d.1295). Durward attended

Henry III on the Gascon expedition of August 1253, on which occasion he

seems to have been doing service for the earl of Strathearn. He

also seems to have been present at Prince Edward's marriage with

Eleanor of Castile.

In August 1255, Earl Richard Clare of Gloucester and John Mansel were

sent towards Scotland to help the king's beloved friends, the earls of

Dunbar and Strathearn together with Alan Durward. It was these

nobles who advised the king and queen to appeal to the king of England

for help. This he did and on 21 September 1255 King Henry engaged

to make no peace with Alexander's adversaries unless with the royal

couple's consent. By this time Alan was reinstalled in Scotland

as justiciar and a leading member of the new royal council.

However, on 29 October 1257, the king was abducted from his bed at

Kinross and a new council was inaugurated by the earl of

Menteith. Durward, termed by the Melrose chronicler, 'the

architect of all the evil', fled to England again.

At this time Alan was in receipt of a pension of £50 a year from

Henry III. On 24 December 1257, his royal pension was exchanged

for the manor and castle of Bolsover, which he continued to hold free

from tallage until at least October 1274 and possibly until his

death. Early in 1258, the king of Scotland's new council mustered

their army at Roxburgh to take vengeance on his late tutors, who had

promised to appear at Forfar and there render an account of their

alleged misdeeds. Despite this, King Henry gave orders to receive

Durward into Norham castle, and looked after his expenses (2-5

April). In September commissioners met at Jedwood, where a peace

was made between the opposing parties after a three weeks'

discussion. This decided that the royal council should consist of

8 lords, four being chosen from each party. Although Durward was

a member of this body, the power seems to have been almost entirely

vested in the hands of the Comyns. The agreement seems to have

worked, for two years later on 16 November 1260, 'Alan Ostiarius' was

one of the 4 barons who undertook to protect Scottish interests while

Queen Margaret was confined in England with her first child. He

seems to have been in financial difficulties in later years and was in

danger of destraint for debt. His death is recorded under 1268 in

a border chronicle which retells the tale of how year on year he

demanded increasing rents from his tenants, promising each time that

this would be the last increase and offering his right hand in honour

of the bargain. Eventually one of his tenants cried out for his

left hand at this as the right had deceived him so often. It is

to be wondered if these financial extortions were not linked with the

fortification of his lands in his continual difficulties.

Durward's wife, Margery, the illegitimate daughter of King Alexander

II, seems to have outlived him, but was dead by 1292, when Nicholas

Soulis, her grandson, set up a claim to the Scottish throne through Alan and Margaret's

younger daughter, Ermengarde Durward. Meanwhile Alan, apparently leaving

three daughters as heiresses, had his lands divided. Some would

have passed to the Soulis family and some to the earls of Fife after

his daughter, Anna, married Earl Colban (d.1270) before 1262.

That said, it cannot be certain what happened to Urquhart castle, even

though it must have been in existence at this time. The castle is

first mentioned eleven years later when it was acquired by Edward I of

England in 1296 in the aftermath of King John Balliol's revolt.

Edward then appointed William Fitz Warin as constable. William is

usually ignored as an English interloper, but he was husband to Mary

Argyll of the Isles (bef.1245-1302) - a MacDougal descendant of

Somerled (d.1164) - and a long term adherent to James Stewart

(d.1310). It is not known how he came to Scotland, for he was a

grandson of Fulk Fitz Warin (bef.1150-98), a claimant to Whittington Castle

in Shropshire, and a son of Alan Fitz Warin of Wantage who had died in

1234. William was therefore in his 60s by the late 1290s.

In the early summer of 1297 William reported back to his king that Andrew Moray [see Dirleton castle] had joined with some evilly disposed people in Avoch (Awath) castle in Ross. After this Alexander Pilchys and Reginald Cheyne [Duffus castle

and an in-law of the Morays], wrote asking him to meet them at

Inverness the Sunday after Ascension day. While returning from

Inverness, Moray and Pilchys and their abetters, set upon William,

wounded him and took him and another man prisoner as well as 18

horses. The next day the 2 rebels besieged Urquhart castle and

Countess Euphemia of Ross sent a serjeant to say that this was not

her doing and that she was willing to assist William. Moray

remained before the castle with his army and the burgesses of

Inverness, but the countess' army then appeared under her son,

Hugh. William then dismissed an envoy of the attackers and the

countess' son helped the Edwardian royalists provision the

castle. That night the enemy attacked and three of the defenders

were killed including William's son, Richard. The besiegers then

withdrew to the castles of Avoch and Balvenie and the woods there

about. By 25 July William was back in Inverness where he wrote

his letter to the king asking him to release the countess' husband in

respect for the countess' assistance. Despite this request, Earl

William, who had been captured at Dunbar in April 1296, was not

released until Michaelmas 1303. After this summer 1297 expedition

Moray withdrew to the south to fight and die at Stirling bridge. The

disaster for royal forces there must have led to the abandonment of the

castle, since in 1298 Urquhart was held for the regent of King John

Balliol, while Fitz Warin had retired to Stirling castle where he was

captured when the castle fell. He was then shipped to Dumbarton castle,

where he must have died soon afterwards, for he and his wife were later

buried in London. Indeed we can suggest from the prayer of Mary

‘who was the wife' of William Fitz Warin asking for the king to

swap the body of her husband for that of Henry St Clair, that William

was dead by 20 February 1299.

There is a ridiculous story that in 1303 King Edward I stormed Urquhart castle

and put the constable, an invented character, Alexander Forbes, and his

sons as well as all the garrison to death. In fact Edward

besieged Brechin castle this summer and campaigned as far north as

Aberdeen, but there is no indication that he reached the Great Glen and

indeed all contemporary chroniclers ‘neglect' to record any

bloodthirsty siege of Urquhart this year. It would seem that in

reality (if not in Wikipedia & Historic Scotland!) King Edward

simply installed Alexander Comyn (d.1308) as lord of the destitute

castle and surrounding lands during this campaign and there was no

tangible opposition to this act at the time. Alexander was the

brother of Earl John Comyn of Buchan (d.1308), the second cousin of the

John Comyn who was to be murdered by Robert Bruce in 1306. This

meant that in 1304 Alexander was holding what were described as two of

the strongest castles in the Scotland, Orcharde and Taradale (Tarwedle).

Presumably Alexander repaired any damage done to the castle which had

occurred with the overthrow of William Fitz Warin in 1297.

There is a ridiculous story that in 1303 King Edward I stormed Urquhart castle

and put the constable, an invented character, Alexander Forbes, and his

sons as well as all the garrison to death. In fact Edward

besieged Brechin castle this summer and campaigned as far north as

Aberdeen, but there is no indication that he reached the Great Glen and

indeed all contemporary chroniclers ‘neglect' to record any

bloodthirsty siege of Urquhart this year. It would seem that in

reality (if not in Wikipedia & Historic Scotland!) King Edward

simply installed Alexander Comyn (d.1308) as lord of the destitute

castle and surrounding lands during this campaign and there was no

tangible opposition to this act at the time. Alexander was the

brother of Earl John Comyn of Buchan (d.1308), the second cousin of the

John Comyn who was to be murdered by Robert Bruce in 1306. This

meant that in 1304 Alexander was holding what were described as two of

the strongest castles in the Scotland, Orcharde and Taradale (Tarwedle).

Presumably Alexander repaired any damage done to the castle which had

occurred with the overthrow of William Fitz Warin in 1297.

With the death of King Edward I in July 1307, Robert Bruce marched through the Great Glen apparently taking the castles of Inverlochy,

Urquhart and Inverness and bringing Earl John Comyn of Buchan to defeat

at the battle of Slioch that Christmas. Taradale castle fell and

was destroyed in March 1308, before John was defeated again in May at

the battle of Inverurie. By this time the castles to the north and west,

including Urquhart, had almost certainly fallen, Urquhart apparently

due to its ‘insufficient garrison'. It is stated that all

these castles taken by Bruce were then destroyed. Both Earl John

Comyn, who was still alive in England after 11 August, and his brother

Sheriff Alexander were dead by 3 December 1308. As they were both

relatively young men the implication might be that they were both

further victims to the Bruce, though no chronicle boasts this. In

1311 Alexander's widow, Joan Latimer (d.1340), bemoaned the fact that

all their Scottish lands ‘were lost through the war' and that she

was forced to live in Yorkshire in poverty.

Whatever happened to Urquhart in 1307/8, the castle or its site, was

probably given to Thomas Randulph in 1312 when he was made earl of

Moray. As such Urquhart castle may have become his

caput. The castle was again operational by 1329 when Robert

Lauder of Quarrelwood was constable, no doubt of the earl, who died on

20 July 1332. Lauder fought and was defeated at the battle of

Halidon Hill on 19 July 1333 under Earl John of Moray, before returning to

hold Urquhart against another threatened invasion. The fortress,

as Wrqwharde, was recorded as

being one of only five castles in Scotland held in the name of King

David II (d.1371) at this time. There is no evidence that the castle

changed hands or was attacked during this war and in 1342 King David

spent the summer hunting at Urquhart. Earl John of Moray was

killed at the battle of Neville's Cross on 17 October 1346 and the castle

reverted to the Crown rather than being inherited by his heirs, the

husbands of his two sisters, who were both married into the powerful

Dunbar family.

In the power vacuum in Scotland after the capture of King David in

1346, Lord John Macdonald of the Isles (d.1386) intruded himself into Moray and

took control of Urquhart castle. It was only in 1369 that King

David marched to Inverness and reclaimed the lost earldom from John,

who retained Lochaber together with Inverlochy castle.

The king seems to have retained Urquhart in his own hands until his

death on 22 February 1371. His successor, King Robert II, on 9

March 1372, only granted John Dunbar, the true heir of Urquhart, the

lowland portion of the earldom of Moray around Inverness without the

lordships of Lochaber (Inverlochy) and Badenach or the castle of Wrochard

with its barony. This was because he had already, on 19 June

1371, granted the castle and barony of Vrchard to his son, Earl David

of Strathearn (d.1386). By 1385 David's elder half brother, Earl Alexander

of Buchan, had taken control of Urquhart castle. David died

before 1386 was out, leaving his brother, known as the wolf of

Badenoch, as lord of the fortress until 1395, when King Robert III

resumed the castle.

In 1395 Lord John's son, Donald of Islay (d.1423), reopened the matter of Moray

by seizing Urquhart castle from the Crown and giving it to his brother,

Alexander, the lord of Lochaber and Inverlochy castle.

In reply, on 22 April 1398, parliament demanded that the castle should

be taken into the hands of the king, ‘who shall entrust the

keeping of it to good and sufficient captains until the kingdom be

pacified, when it shall be restored to its owners'. Despite this

Donald and Alexander retained the fortress, until in 1411, the

Highlanders marched on Aberdeen, only to be checked by the king's

supporters under the earl of Mar, who was lord of Kildrummy castle, at

the battle of Harlaw. Although the particularly bloody battle

proved indecisive, Donald subsequently lost the initiative and the

Crown, in the form of the earl of Mar, eventually retook Urquhart

castle in July 1429. The castle was not restored to its rightful

owners, the descendants of Alan Durward, but in 1429 just £2 was

spent on its repair by the Crown. This would suggest that the

castle was both inhabitable and fortified. In 1437 Donald's son,

Earl Alexander of Ross (d.1449), raided around Glen Urquhart, but could not take

the castle. Ten years later the Crown spent the paltry sum of

£21 12s 4d on constructing new buildings and repairing old ones,

as well as in part payment of the garrisons of Urquhart and

Inverness. Further unspecified payments followed.

Alexander's son, John Macdonald (d.1498), succeeded his father in 1449, aged 16. In

1452, during the Douglas rebellion, he too led a raid up the Great

Glen, seized Urquhart and subsequently obtained a grant of the lands

and castle for life in 1456. However, in 1462 John made an

agreement with King Edward IV of England (d.1483) against the Scottish King James III (d.1488)

known as the treaty of Ardtornish-Westminster, which aimed at the dismemberment of Scotland. When this became known to

James, John was stripped of his titles in 1476 and Urquhart was turned

over to the earl of Huntly. He brought in Duncan Grant of

Freuchie to impose his rule in the area. Duncan's son, John Grant

of Freuchie (d.1538), was given a 5 year lease of Glen Urquhart in

1502. In 1509 the castle, along with the estates of Glen Urquhart

and Glenmoriston, were granted by James IV to John Grant in perpetuity,

on condition that he:

repair or build at the castle

a tower, with an outwork or rampart of stone and lime, for protecting

the lands and the people from the inroads of thieves and malefactors;

to construct within the castle a hall, chamber and kitchen, with all

the requisite offices, such as pantry, bakehouse, brewhouse, oxhouse,

kiln, cot, dovegrove and orchard with the necessary wooden fences.

This looks very much like the sixteenth century refurbishment of

the keep in the outer ward. The Grants then maintained their

ownership of the castle until 1912.

Despite

John's works on the castle, in 1513, following the disaster of Flodden,

Donald MacDonald of Lochalsh attempted to gain from the disarray in

Scotland by claiming the lordship of the Isles and again occupying

Urquhart castle for his family. Grant regained the castle before

1517, but not before the MacDonalds had driven off 300 cattle and 1,000

sheep, as well as looting the castle of provisions for which Grant

unsuccessfully attempted to claim damages. In 1527 the castle was

described as ‘the famous castle of Urquhart, of which the ruinous

walls remain yet'.

Despite

John's works on the castle, in 1513, following the disaster of Flodden,

Donald MacDonald of Lochalsh attempted to gain from the disarray in

Scotland by claiming the lordship of the Isles and again occupying

Urquhart castle for his family. Grant regained the castle before

1517, but not before the MacDonalds had driven off 300 cattle and 1,000

sheep, as well as looting the castle of provisions for which Grant

unsuccessfully attempted to claim damages. In 1527 the castle was

described as ‘the famous castle of Urquhart, of which the ruinous

walls remain yet'.

James Grant of Freuchie (d.1553) in 1544 became involved with Huntly

and Clan Fraser in a feud with the MacDonalds of Clanranald, which

culminated in the battle of the Shirts. In retaliation the

MacDonalds and their allies the Camerons attacked and captured Urquhart

in 1545. Known as the Great Raid, this time the MacDonalds

succeeded in taking 2,000 cattle, as well as hundreds of other animals,

and stripped the castle of:

12 feather beds with the

bolsters, blankets and sheets, value £40; 5 pots value 10 marks

(£6 13s 4d), 6 pans at 10 marks (£6 13s 4d), a basin at

14s, a chest with £300 within it, 2 brewing caldrons worth

£15, 6 spits at £3, barrels of oats, pewter vessels to the

value of £40, 20 pieces of artillery and suits of armour worth

100 marks (£66 13s 4d), locks, yetts, stanchions, beds, chairs,

and other furniture worth 300 marks (£200) and 3 great gates

worth 40 marks (£26 13s 4d).

Although Grant regained the castle, he received no monetary recompense, but did obtain some Cameron lands.

The Great Raid proved to be the last of this kind. As early as

1527 the historian Hector Boece had written of the 'rewinous wallis' of

Urquhart. In the late sixteenth century Urquhart was again repaired by the

Grants. These repairs and remodellings continued as late as 1623,

but did not stop the Covenanters getting into the castle over Christmas

1644 when they ‘utterly spoiled, plundered and abused... the

mansion and manor place of Wrquhart', as it was written up in June

1647. When Oliver Cromwell invaded Scotland in 1650, he

apparently disregarded Urquhart as a stronghold in favour of building

forts at either end of the Great Glen. Despite this, the castle

was repaired again in 1676 at a cost of 200 marks (£133 6s 8d).

The fortress must still have been defensible, for when James VII was

deposed in the Revolution of 1688, Ludovic Grant of Freuchie sided with

William of Orange and garrisoned the castle with 200 of his own

soldiers. The garrison was re-provisioned by the loch when a

force of 500+ Jacobites laid siege and the garrison held out until

after the defeat of the main Jacobite force at Cromdale in May

1690. When the soldiers finally left in 1692 they blew up at

least the gatehouse to prevent reoccupation of the site by the

Jacobites. Large blocks of collapsed masonry are still visible

from this slighting. Parliament ordered £2,000 compensation

to be paid to Grant ‘for the damnifying of the house of

Urquhart...'. Subsequent plundering of the stonework and other

materials for re-use by locals further reduced the fortress to

ruins. In 1708 it was claimed that the lead of the castle had

been stolen from one of the vaults as well as ‘parts of the

partitions of the chambers'. Finally the Grant tower partially

collapsed following a storm in 1715, assuming that this was the part of

Urquhart castle ‘blown down with the last storm of wind, the SW

side thereof to the low (laich) vault'. By the 1770s the castle

was roofless and regarded as a romantic ruin.

Coins recovered during the clearances of the castle ranged it date from

the time of Edward I to Charles II (1272-1685). Much earlier, in

1825, a hoard of silver pennies of the Alexanders, Davids, Edwards and

Roberts were uncovered. Unfortunately no record of these was

kept. In 2011 more than 315,000 people visited Urquhart castle,

making it Historic Scotland's third most visited site after the castles

of Edinburgh and Stirling.

Description

Description

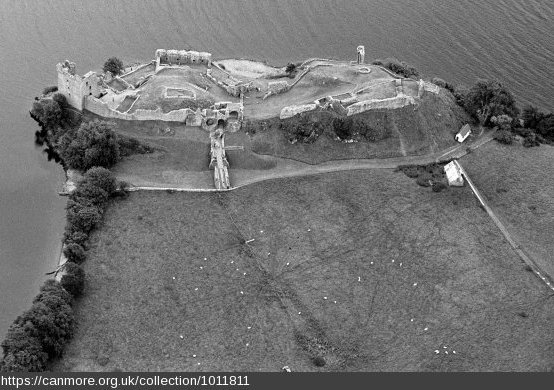

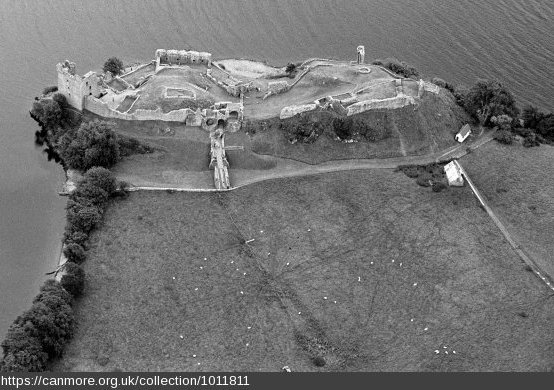

Urquhart castle is sited on Strone Point, a triangular promontory on

the north-west shore of Loch Ness, commanding the route along the north

side of the

Great Glen as well as the entrance to Glen Urquhart. Gardens and

orchards are said to have lain north of the castle in the seventeenth

century. Beyond this area the ground rises steeply to the

north-west. A ditch, 100' across at its widest and up to 16'

deep,

defends the landward approach. A stone causeway bridges the

centre of the ditch with a drawbridge midway. The west entrance

to

this causeway was originally entered through a fine Romanesque arch

similar to the one in the gatehouse. This was still standing at

the end of the eighteenth century. The approach from the

drawbridge to

the gateway was formerly walled-in, forming a long, enclosed

barbican. Such long barbicans are more common in Wales (Carreg Cennen,

Denbigh) and are associated with a spear defence, rather than

projectile weapons. The drawbridge would have to have been

operated from the wallwalk of this structure and four great beam holes

can be seen in the masonry on the east side where the structure was housed.

The fortress is shaped like a pair of spectacles with each lens forming

a bailey and the dividing bridge being the lowest point of the

fortress. It is about 520' long by 190' at its widest and 100' at

its narrowest in the centre. The upper bailey is to the south and the

lower or nether bailey to the north. The curtain walls of both

enclosures are said to date to the fourteenth century though study of the

site would suggest otherwise.

The supposedly sixteenth century gatehouse, 52' wide, is on the inland side

of the lower (nether) bailey, and comprises twin D shaped towers of 21'

diameter, flanking a 10' wide barrel vaulted entrance passageway.

The Romanesque gate arch is similar to the thirteenth century ones at Harlech

and Beaumaris in Wales. Formerly the passage was defended by a

portcullis and a double set of outward opening doors. The ceiling

above this section was wooden, while a partially built up recess may

have been a guard's box. The north tower basement could be entered

after the gate, suggesting that this was the guardroom. Although

the upper floor of this north tower is gone there are remains of a barrel

vaulted roof in both towers as well as one at first floor level in the south

tower. Beyond the guardroom door there were two more sets of

gates before the ward could be entered. Over the entrance are a

series of rooms which probably housed the castle constable.

A close examination of the south side of the gatehouse shows that there are

at least 3 phases to the structure. Most plainly the earliest

part of the structure was the north curtain wall coming down from the old

citadel to the south, although half the length of this section nearest the

gatehouse has been deliberately destroyed. The remaining fragment

of curtain has been built up within the gatehouse and has obviously had

the rectangular chamber of the south tower added to it at the rear.

Similarly, to the west, the semi-circular front has been added to the wall

on a slightly different alignment. This rounded front has loops

in it which are lacking in the north tower, which would therefore appear to

have been rebuilt, possibly marking a fourth construction phase.

Further, the barbican walls appear to underlie the towers and are not

aligned with the structure. As the curtain walls on either side

of the gatehouse are not aligned and are of different styles and

thicknesses (the south wall consists of two separate phases, a 5' thick

wall to the east which has been faced to the west with a 3' thick wall to

make an 8' thick wall) it rapidly becomes apparent that much building

and rebuilding has gone on at the castle. The placing of a kiln

within the south tower probably dates to the order of 1509. The

misreading of this order is probably why the tower is wrongly said to

be sixteenth century in its entirety!

To the north of the gatehouse is an attached garderobe turret that was at

least 2 storey's high over its basement. The lowest storey

appears to have been a prison, entered from the north tower of the

gatehouse. This structure appears added later to the curtain and

gatehouse, although its west wall aligns with the curtain running up the

‘motte' on the other side of the gatehouse. The idea that

such a typically thirteenth century gatehouse is sixteenth centry can be easily refuted

by comparing it with the artillery defended gatehouse at Falkland

palace and even the late fourteenth century gatehouse at Stirling, both of

which follow totally different plans. Collapsed masonry surrounds

the gatehouse from its blowing up in 1692.

The

lower bailey, with most of the main castle buildings like kitchen, hall

and apartments, is anchored at its northern tip by the Grant

Tower. This keep-like structure measures 39' by 36', is 50' high

and has walls up to 12' thick. The tower is said to rest on

fourteenth

century foundations, due to the similarities of the tower to

workmanship at Tantallon castle and David's Tower at Edinburgh castle,

but is otherwise sixteenth century. Certainly one of the ‘16th

century' windows has the base of a (thirteenth century?) crossbow loop with

diagonal tooling still retained in its lower courses. Originally

of 4 storeys, the standing parts of the tower parapet were remodelled

in the 1620s, when the 4 corners were topped by corbelled-out

bartizans. Above the main door to the west and the double-gated

postern to the east, are machicolations, while the west door is protected by

its own ditch and drawbridge. This was accessed via a cobbled

‘inner close' separated from the lower bailey by a gate.

There is a circular staircase built into the east wall of the tower which

links the upper floors. Another stair beside it goes down to the

basement. The walls are only 8' thick at first floor level.

The rooms on the main floors have large sixteenth century windows with small

pistol-holes beneath.

The

lower bailey, with most of the main castle buildings like kitchen, hall

and apartments, is anchored at its northern tip by the Grant

Tower. This keep-like structure measures 39' by 36', is 50' high

and has walls up to 12' thick. The tower is said to rest on

fourteenth

century foundations, due to the similarities of the tower to

workmanship at Tantallon castle and David's Tower at Edinburgh castle,

but is otherwise sixteenth century. Certainly one of the ‘16th

century' windows has the base of a (thirteenth century?) crossbow loop with

diagonal tooling still retained in its lower courses. Originally

of 4 storeys, the standing parts of the tower parapet were remodelled

in the 1620s, when the 4 corners were topped by corbelled-out

bartizans. Above the main door to the west and the double-gated

postern to the east, are machicolations, while the west door is protected by

its own ditch and drawbridge. This was accessed via a cobbled

‘inner close' separated from the lower bailey by a gate.

There is a circular staircase built into the east wall of the tower which

links the upper floors. Another stair beside it goes down to the

basement. The walls are only 8' thick at first floor level.

The rooms on the main floors have large sixteenth century windows with small

pistol-holes beneath.

To the south of the Grant Tower is a range of buildings constructed along a

curtain wall of varying thicknesses and dates. The heavily

buttressed curtain wall seems to have been 9' thick as it skirted along

above the loch shore. Running east from the water gate curtain it

made one long sweep to the basement of the great hall. Within

were 3 buildings of differing dates. The first building, next to

the water gate, appears the most modern, but it only has a 3' thick

wall for its external south front. There is a doorway here cut

through the curtain and this seems to show that the wall was 2 phase,

like the curtain between the citadel and the gatehouse. Next to

this was a small rectangular chamber with an 8' thick west wall supported

by 2 fine pilaster buttresses. These have a twelfth century

look. The much thinner 4' thick north wall had another singular

buttress centrally, before the irregularly shaped kitchen which filled

the gap before the great hall. This still preserves the bases of

2 windows to the north. The kitchen wall abuts the rectangular great

hall which occupied the central part of this range.

The great hall is 80' by 50' externally with walls 10' thick to the

south-east. This wall is pierced in the basement by four

irregularly

placed window embrasures with lintels. The windows themselves are

surprisingly square, but appear to be original, although some reworking

has been done to some of the embrasure jambs. Similar windows are

to be found in the basements at Lochindorb, Morton, Rait and Duffus

castles as well as in the earliest parts of the Bishop's Palace at

Kirkwall. A doorway joined the basement to the kitchen. The

great hall should have been over the basement, but little now remains

of this floor other than its instep on the curtain wall. Moving north

at 45 degrees from the hall is another large room which had steps

leading down to a basement entrance next to a buttress that appear on

both sides of the wall. The north end of this has been divided off

into another small chamber, similar to the one at the south end, although

the doorway from this enters the inner courtyard. There is a

light to the west. At the east angle of the ward between the hall and

chamber is an open masonry platform. The suggestion is that there

was a derrick here for hoisting supplies from the loch into the castle.

The curtain along this front varies from 3' to 6' thick and is

definitely doubled up again where the north building abuts into the

curtain. This whole front is supported by 5 large buttresses, the

two corner ones being pentagonal rather than rectangular. These

bear some resemblance to those found at Castle Sween, and as such could

be twelfth century.

The west wall of the bailey runs in a series of irregular sweeps from the

Grant Tower to the great gatehouse. The central portion of this

is pierced with four embrasures fitted with loops to cover the

ditch. The section of wall nearest the Grant Tower is thicker

than the rest and abuts onto it. A rectangular building to the south-west

makes up one side of the inner court, while the apartment block makes

up the south side. On the summit of the small rocky mound, centrally

placed in the lower ward, are the rectangular foundations of what is

tentatively identified as a chapel.

On the other side of a weak dividing wall, south-west of the gatehouse, is the

upper bailey, which would appear to be the oldest part of the

castle. The entire site is dominated by a rocky mound at the west

corner of the castle. This rises some 85' above the loch level

(which was raised 6' when the Caledonian canal was built) and 50' from

the ditch bottom. As the highest point of the fortification, this

mound is thought to be the site of the earliest defences at

Urquhart. The evidence for this claim was the discovery of

vitrified material, said to be characteristic of early medieval or late

prehistoric fortifications, on the slopes of the mound. It is

claimed that in the thirteenth century the mound became the motte of the

‘original castle' built by the Durwards, and the surviving walls

represent a shell keep of this date. Such a claim does not stand

up to scrutiny. A motte is generally an artificial, upturned

pudding bowl of soil. The mound at Urquhart is merely an

irregular rocky knoll with little evidence of scarping, let alone

artificial raising. Indeed the ‘motte' is not usually

included amongst the list of 206 known or suspected mottes in

Scotland. Further the ruins on top are also nothing like a

conventional ‘Norman' shell keep - viz Tonbridge, Totnes, Chateau sur Epte, Tretower, Gisors, Lincoln,

Arundel, Berkeley. Such structures tend to be regular and

Urquhart is a most irregular structure and as such will be referred to

as the citadel from now on. The external walls to the north, south and west

are thicker (8'6") than the internal walls (6') and have a unique

character of a striated texture of small, long, close-set stones.

The

citadel ‘keep' itself is unique, being a six sided irregular

rhomboid shape. The only noticeable decoration is a single

stepped plinth to the west which marks the baseline of the building on the

uneven rock surface. This is not visible on the other 3

sides. At the north end is what appears to be a pentagonal shaped

tower, barely projecting past the curtain wall to the north

and forming a

part of the east wall of the ‘keep'. The citadel was

entered

via a ground floor doorway to the east and contained two irregular

chambers, one to the north-east and the other to the south-west.

Presumably the

central portion of the ‘keep' was open to the elements. The

south-west chamber has a doorway and a fireplace in its north wall. The

masonry citadel would appear to be predate the curtain wall defences of

the upper bailey.

The

citadel ‘keep' itself is unique, being a six sided irregular

rhomboid shape. The only noticeable decoration is a single

stepped plinth to the west which marks the baseline of the building on the

uneven rock surface. This is not visible on the other 3

sides. At the north end is what appears to be a pentagonal shaped

tower, barely projecting past the curtain wall to the north

and forming a

part of the east wall of the ‘keep'. The citadel was

entered

via a ground floor doorway to the east and contained two irregular

chambers, one to the north-east and the other to the south-west.

Presumably the

central portion of the ‘keep' was open to the elements. The

south-west chamber has a doorway and a fireplace in its north wall. The

masonry citadel would appear to be predate the curtain wall defences of

the upper bailey.

The south curtain of the upper bailey, 8' thick, runs irregularly along the

crag top to the heights above the loch shore in a series of six

sweeps. At the bottom of the lens is a boldly projecting

rectangular structure with a 45 degree turn towards its north end.

This is thought to be the early castle hall, although it was later used

as a smithy. The thinner internal wall with surviving doorway

seems to indicate that this hall-like building was planned from the

conception of the masonry ward. The south wall, with a great buttress

still standing to its full height, is complete with wallwalk and

remains of the battlements.

At the bridge of the spectacles is a simple water or sea gate which gives

access to the shore of the loch. Sea gates exist at several other Scottish castles, viz. Dunvegan and the others listed there. A rectangular building lay to

the north of this, but its remains are now highly fragmentary. A

cross wall ran from the north-east part of this building to the east wall of the

gatehouse, effectively dividing the castle bailey into two - the upper

and lower lens.

Why not join me at Urquhart and other Great Scottish Castles this Spring? Information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2016

Paul Martin Remfry

Description

Description Urquhart

castle, dating from the sixth century to the seventeenth, stands beside Loch

Ness in the Highlands of Scotland, guarding the fertile Glen Urquhart,

13 miles south-west of Inverness.

Urquhart

castle, dating from the sixth century to the seventeenth, stands beside Loch

Ness in the Highlands of Scotland, guarding the fertile Glen Urquhart,

13 miles south-west of Inverness.

There is a ridiculous story that in 1303 King Edward I stormed Urquhart castle

and put the constable, an invented character, Alexander Forbes, and his

sons as well as all the garrison to death. In fact Edward

besieged Brechin castle this summer and campaigned as far north as

Aberdeen, but there is no indication that he reached the Great Glen and

indeed all contemporary chroniclers ‘neglect' to record any

bloodthirsty siege of Urquhart this year. It would seem that in

reality (if not in Wikipedia & Historic Scotland!) King Edward

simply installed Alexander Comyn (d.1308) as lord of the destitute

castle and surrounding lands during this campaign and there was no

tangible opposition to this act at the time. Alexander was the

brother of Earl John Comyn of Buchan (d.1308), the second cousin of the

John Comyn who was to be murdered by Robert Bruce in 1306. This

meant that in 1304 Alexander was holding what were described as two of

the strongest castles in the Scotland, Orcharde and Taradale (Tarwedle).

Presumably Alexander repaired any damage done to the castle which had

occurred with the overthrow of William Fitz Warin in 1297.

There is a ridiculous story that in 1303 King Edward I stormed Urquhart castle

and put the constable, an invented character, Alexander Forbes, and his

sons as well as all the garrison to death. In fact Edward

besieged Brechin castle this summer and campaigned as far north as

Aberdeen, but there is no indication that he reached the Great Glen and

indeed all contemporary chroniclers ‘neglect' to record any

bloodthirsty siege of Urquhart this year. It would seem that in

reality (if not in Wikipedia & Historic Scotland!) King Edward

simply installed Alexander Comyn (d.1308) as lord of the destitute

castle and surrounding lands during this campaign and there was no

tangible opposition to this act at the time. Alexander was the

brother of Earl John Comyn of Buchan (d.1308), the second cousin of the

John Comyn who was to be murdered by Robert Bruce in 1306. This

meant that in 1304 Alexander was holding what were described as two of

the strongest castles in the Scotland, Orcharde and Taradale (Tarwedle).

Presumably Alexander repaired any damage done to the castle which had

occurred with the overthrow of William Fitz Warin in 1297. Despite

John's works on the castle, in 1513, following the disaster of Flodden,

Donald MacDonald of Lochalsh attempted to gain from the disarray in

Scotland by claiming the lordship of the Isles and again occupying

Urquhart castle for his family. Grant regained the castle before

1517, but not before the MacDonalds had driven off 300 cattle and 1,000

sheep, as well as looting the castle of provisions for which Grant

unsuccessfully attempted to claim damages. In 1527 the castle was

described as ‘the famous castle of Urquhart, of which the ruinous

walls remain yet'.

Despite

John's works on the castle, in 1513, following the disaster of Flodden,

Donald MacDonald of Lochalsh attempted to gain from the disarray in

Scotland by claiming the lordship of the Isles and again occupying

Urquhart castle for his family. Grant regained the castle before

1517, but not before the MacDonalds had driven off 300 cattle and 1,000

sheep, as well as looting the castle of provisions for which Grant

unsuccessfully attempted to claim damages. In 1527 the castle was

described as ‘the famous castle of Urquhart, of which the ruinous

walls remain yet'. Description

Description The

lower bailey, with most of the main castle buildings like kitchen, hall

and apartments, is anchored at its northern tip by the Grant

Tower. This keep-like structure measures 39' by 36', is 50' high

and has walls up to 12' thick. The tower is said to rest on

fourteenth

century foundations, due to the similarities of the tower to

workmanship at Tantallon castle and David's Tower at Edinburgh castle,

but is otherwise sixteenth century. Certainly one of the ‘16th

century' windows has the base of a (thirteenth century?) crossbow loop with

diagonal tooling still retained in its lower courses. Originally

of 4 storeys, the standing parts of the tower parapet were remodelled

in the 1620s, when the 4 corners were topped by corbelled-out

bartizans. Above the main door to the west and the double-gated

postern to the east, are machicolations, while the west door is protected by

its own ditch and drawbridge. This was accessed via a cobbled

‘inner close' separated from the lower bailey by a gate.

There is a circular staircase built into the east wall of the tower which

links the upper floors. Another stair beside it goes down to the

basement. The walls are only 8' thick at first floor level.

The rooms on the main floors have large sixteenth century windows with small

pistol-holes beneath.

The

lower bailey, with most of the main castle buildings like kitchen, hall

and apartments, is anchored at its northern tip by the Grant

Tower. This keep-like structure measures 39' by 36', is 50' high

and has walls up to 12' thick. The tower is said to rest on

fourteenth

century foundations, due to the similarities of the tower to

workmanship at Tantallon castle and David's Tower at Edinburgh castle,

but is otherwise sixteenth century. Certainly one of the ‘16th

century' windows has the base of a (thirteenth century?) crossbow loop with

diagonal tooling still retained in its lower courses. Originally

of 4 storeys, the standing parts of the tower parapet were remodelled

in the 1620s, when the 4 corners were topped by corbelled-out

bartizans. Above the main door to the west and the double-gated

postern to the east, are machicolations, while the west door is protected by

its own ditch and drawbridge. This was accessed via a cobbled

‘inner close' separated from the lower bailey by a gate.

There is a circular staircase built into the east wall of the tower which

links the upper floors. Another stair beside it goes down to the

basement. The walls are only 8' thick at first floor level.

The rooms on the main floors have large sixteenth century windows with small

pistol-holes beneath. The

citadel ‘keep' itself is unique, being a six sided irregular

rhomboid shape. The only noticeable decoration is a single

stepped plinth to the west which marks the baseline of the building on the

uneven rock surface. This is not visible on the other 3

sides. At the north end is what appears to be a pentagonal shaped

tower, barely projecting past the curtain wall to the north

and forming a

part of the east wall of the ‘keep'. The citadel was

entered

via a ground floor doorway to the east and contained two irregular

chambers, one to the north-east and the other to the south-west.

Presumably the

central portion of the ‘keep' was open to the elements. The

south-west chamber has a doorway and a fireplace in its north wall. The

masonry citadel would appear to be predate the curtain wall defences of

the upper bailey.

The

citadel ‘keep' itself is unique, being a six sided irregular

rhomboid shape. The only noticeable decoration is a single

stepped plinth to the west which marks the baseline of the building on the

uneven rock surface. This is not visible on the other 3

sides. At the north end is what appears to be a pentagonal shaped

tower, barely projecting past the curtain wall to the north

and forming a

part of the east wall of the ‘keep'. The citadel was

entered

via a ground floor doorway to the east and contained two irregular

chambers, one to the north-east and the other to the south-west.

Presumably the

central portion of the ‘keep' was open to the elements. The

south-west chamber has a doorway and a fireplace in its north wall. The

masonry citadel would appear to be predate the curtain wall defences of

the upper bailey.