Burton in Lonsdale

The fortress, just north of the River Greta, would have commanded the route from Hornby and thereby Lancaster, to Ingleton and thereby to Skipton.

Despite its positioning on a major routeway and being a centre of

Mowbray lordship, the history of Burton castle is generally built up of

hearsay. To cut this away the following will list the recorded

original documentation about the castle, which will be followed by some

speculation.

Just before the Norman Conquest, Burton (Bortaine)

was part of the manor of Whittington vill in the Lune valley.

This had been owned by Tostig, the younger brother of King Harold and

had been and apparently was waste. Tostig was slain at the Battle

of Stamford Bridge, although the site had presumably passed to his

elder brother on Tostig's exile. After the death of King Harold, King William I (1066-87) would seem to have continued to hold Burton until some point after Domesday in 1086 when either he, or his son, King William Rufus

(1087-1100), appears to have granted the manor and possibly the

fortress too, to Earl Robert Mowbray of Northumbria. Certainly

the manor was later found as the administrative centre for the

surrounding Mowbray estates in Yorkshire and Lancashire.

Meantime Earl Robert was disinherited in 1095, ending his days after a

long time in prison as a monk at St Albans abbey. Burton and

presumably its castle were resumed by the Crown on Robert's

imprisonment. At some point King Henry I

(1100-35) regranted the Mowbray lands to Robert's ex wife, Matilda

Laigle, before 1108, when she married Nigel Aubigny (d.1129). On

the death of her brother, Gilbert Laigle, in 1114, Nigel divorced

Matilda and married Gundreda Gournay in June 1118. However, King Henry I

obviously allowed Nigel to keep the Mowbray lands and they were seized

by the Crown, before 29 September 1129 when Henry I had taken control

of the lands lately held by the now obviously deceased Nigel.

Before the pipe roll was drawn up, the king had passed the lands on to

Robert Wyville and Henry Montfort and amongst the allowances made to

them was £21 5s 10d for the force kept in Burton in Lonsdale

castle. This consisted of 1 knight, 10 serjeants, a porter and a

watchman. Mowbray's other castles were Brinklow, Kendal, Kirkby Malzeard and Thirsk.

By 1138 Nigel's only surviving son and heir, Roger, who took the

surname Mowbray, had inherited all his father's lands. Roger then

fought in the battles of the Standard (1138) and Lincoln (1141), before

joining in the second Crusade in 1148. It was possibly at this

time that he granted Lonsdale, Kendal

and

Horton to William Fitz Gilbert Lancaster (d.1170). Certainly that

was thought by the time of Kirkby's Inquest in the reign of Edward I

(1272-1307) when it was found that the lands in question were Sedbergh,

Garsdale, Dent, Thornton in Lonsdale, Burton in Lonsdale, Bentham,

Clapham with Newby, Austwick, Lawkland and Horton in Ribblesdale.

Burton castle therefore seems to have

been held as the 2 fees owed by William to Roger Mowbray in 1166.

Presumably the castle remained in Mowbray hands, or reverted to them on

the death of the last William Lancaster in 1184.

A little before 21 November 1297, King Edward I took control of the manor of Burton in Lonsdale on the death of Roger

Mowbray. As Roger's son was only 12 at the time the manor and

presumably the castle site remained with the king for the rest of his

life; John Mowbray coming of age in 1307 and being executed by Edward IIin

1322. By the time of the death of his son in 1361, another

John Mowbray, the castle is supposed to have been abandoned as it is

not mentioned in the survey of Burton in Lonsdale. However, its

lack of mention in the vill as early as 1297 may suggest that it had

already been abandoned by this earlier date. Certainly on 3 April

1325, an inquistion post mortem found that the land of John Fitz

Matthew Burgh was 'a ruinous messuage' in Burton in Lonsdale, 'laying

waste from the devastation of the Scots'. Such devastation may

well have included the final abandonment of the castle.

Description

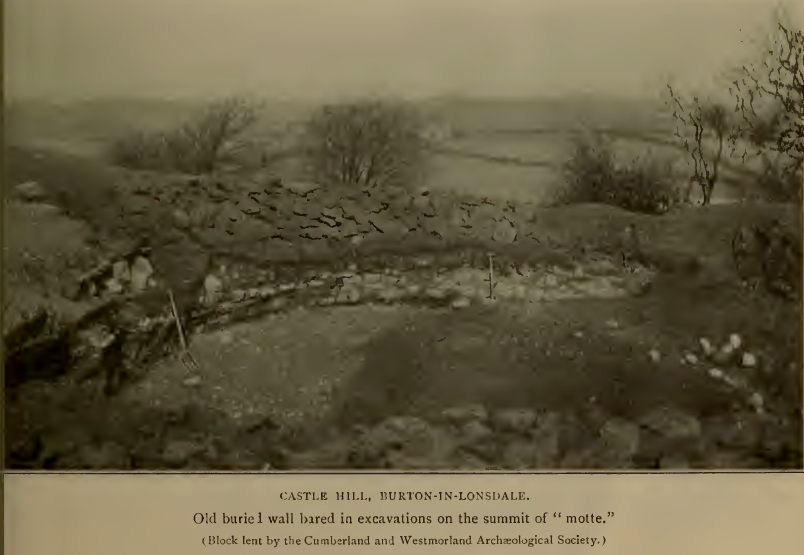

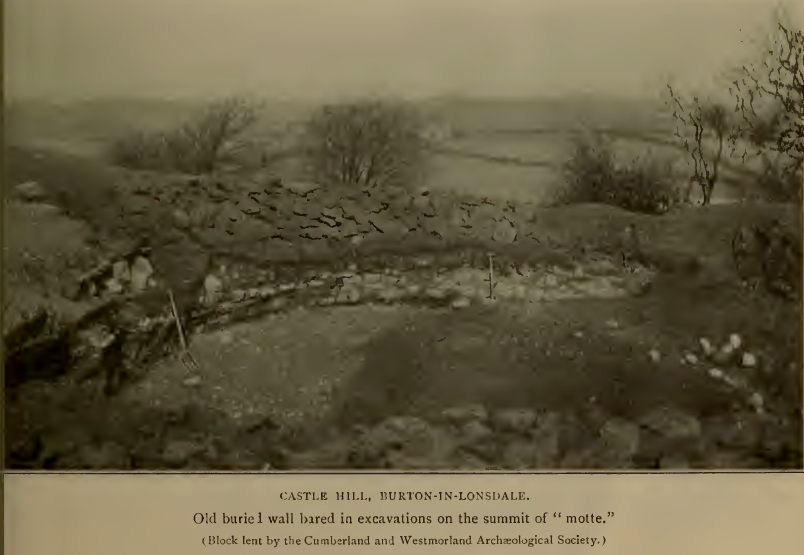

Castle Hill is an aberrant motte and bailey castle. The mound is

some 30' high and is an odd east to west oval shape, the summit being

some 110' across and 70' wide. Its height may suggest that it was

a royal foundation. Set centrally upon this odd mound are the poor remnants of what appears to have been a round tower keep

which was some 65' in diameter with walls over 5' thick. The size

of this makes it somewhat similar to the keep on the motte at Berkhamsted.

However, here the motte is an odd shape, having an east to west

orientation. This virtually proves that the motte predates the

tower and that the masonry structure is not emmotted. If this

were the case why would the soil have been piled up around the tower in

such an odd manner. The walls of the tower, assuming that it is

not a shell keep, which would have more likely followed the contours of

the motte top, are built of local rubble.

The motte ditch is best preserved to the west where it is about 10'

deep. To the east it appears to have been encroached upon by the

raised platform which leads to a farmyard. The main bailey lies

to the west and consists of a curved rectangular ward about 190' by

170' and surrounded by a ditch still up to 6' deep. A further

half moon bailey lies to the south.

Excavations carried out in 1904 found that most finds ‘had silted

down through the soft soil to a uniform level'. This found that

at a depth of 4' under current ground level the whole site, or those

parts of it that were excavated, ie in the trenches on the motte,

baileys, ditches and banks, had all been cobbled with rough pebbles

bedded in a basis of stiff clay. On the motte top this

‘paving' formed a ‘shallow saucer-like concavity... that

sloped rapidly' up to the foundations of the keep walls although these

were several inches above the pavement. This would suggest that

the paving was laid down and the masonry afterwards, possibly when the

paving had been forgotten. Imposed on the paving was a think

layer of black ash containing pieces of charred, unworked wood together

with large amounts of fragments of animal bone, including part of a

human skull. Elsewhere on the motte possible graves were found

also with burnt material within them. Pits of 12' and 20' were

dug into the motte suggesting that it consisted of sand laid on glacial

clay and that it was then encased with a crust of clay into which

pebbles had been driven to form a protective shell. Evidence of a

lower mound, also encased with a pavement was found some 4' below the

foundations. As finds on the pavement included a perfect bone

needle and a flint arrowhead, it was presumed that the mound was

originally prehistoric and then reused as a castle motte.

Excavation also uncovered on the motte pavement were 2 coins of Henry II

(1154-89) and ‘Norman' arrowheads and knives, along with a large

key and probably civil war tobacco pipes and a coin of Charles I.

Another coin that came off the motte top was a brass coin thought to be

of Tiberius (d.37AD). The conclusion of the excavators was that

the bailey and lower banks and even the mound may have been prehistoric

and then reused as a castle by the Normans. Their thoughts on

what appears to be a keep is even more odd, dating it to the fourteenth

century and suggested that it was ‘a retaining wall', although

what it was retaining on top of a mound was not thought a relevant

subject for speculation. Similar excavations on a mound at

Arkholme found a similar pavement with burnt deposits on it at a depth

of 9'.

From the above it is suggested that the fortress began as a prehistoric

ritual site and then was made into a Norman fortress some time after

the 1060s and refortified with a great round tower, possibly in the

twelfth century. That the castle continued in use into the

fourteenth century seems somewhat unlikely judging by the 1297 survey and a lack of excavation finds.

Copyright©2021

Paul Martin Remfry