Kenilworth Castle

The site of Kenilworth castle was under the

control of Geoffrey Clinton (d.1131/33) before 1122 when the fortress

was mentioned in Geoffrey's foundation charter of Kenilworth

priory. This is traditionally dated to 1122 and must have been

made around then. This leaves the question as to when the castle

was founded and what can be said of Geoffrey Clinton and his

family? Firstly, Geoffrey is relatively well known amongst

medievalists, but that said he doesn't seem to have been studied for

himself, but has merely been used as a dim light to help illuminate the

political edifice of Henry I (1100-35).

Initially, it is worth repeating that Geoffrey was one of those said by one contemporary to be of ignoble blood (de ignobili stirpe), who had been ‘raised from the dust' (de pulvere) by King Henry I

(1100-35). Another early chronicler claimed that Geoffrey

proffered £2,000 to Henry I if he would make Geoffrey's nephew,

Roger Clinton (d.1148), a bishop. Regardless of the alleged

bribe, Roger was duly consecrated bishop of Coventry on 22 December

1129. Certainly no such payment appears on the pipe roll of that

year which, alone from Henry's reign, has happened to survive.

Once again this shows the dangers of accepting the petty jealousies and

downright propaganda that appear in various works, both modern and

ancient (as well as their successors on TV), at face value.

Despite this, and the possibility that the money was never placed

‘on the books', it is still possible to discover a lot more of

Geoffrey's antecedents than is generally acknowledged.

King Henry I's own confirmation

charter to Geoffrey's foundation of Kenilworth priory of October 1125,

stated that he had permitted Geoffrey Clinton, his treasurer and

chamberlain, to found the church of St Mary in Kenilworth on land which

he had given to Geoffrey in fee and inheritance and that the king

confirmed to the church the lands that the monks had acquired or may

acquire. Currently these included the land of Kenilworth given by

Geoffrey to Prior Bernard, as well as land in Salford Priors, Idlicote,

Tysoe, Newham

Regis and Lillington. These were all vills held by

Geoffrey. To this the king added the church of Wootton Leek with

land in Wootton, Lillington, the churches of Kington, Stoneleigh and

Bidford, as well as the churches of Brailes and Wellesbourne which had

been given by Earl Roger of Warwick (d.1153). Additional to these

were the churches of Kington and Barton Segrave given by others.

Amongst the witnesses to this royal document was Geoffrey himself.

It is useful that a copy of Geoffrey's original grant survives.

This states that Geoffrey had founded the church of Kenilworth (Chenilleuurda) in honour of St Mary and had conceded to the canons there:

all the land in the plain of

Kenilworth itself and the wood and all the rest of the aforesaid vill

with the exception of the parts which I retain at the castle and to

make my park...

In a later charter Geoffrey conceded:

...the full tithe of all

things whatsoever and from wherever they came to my castle, whether to

the cellar, or to the kitchen, or to the larder, or to the granary, or

to the ‘halgard'...

King Henry I (1100-35) confirmed the grant or grants to Kenilworth priory. These included:

all the land of Kenilworth in

the forest and the plain, which the same Geoffrey gave to Prior Bernard

for the work of the same church, except only for that land in which his

castle is situated, and which he retained in his possession to make his

town, and for his fishery, and for his park...

King Henry II (1154-89) also made a confirmation grant to Kenilworth. Interestingly this was for all the things that his grandfather, King Henry I

(1100-35), gave to Kenilworth priory in alms and as his charter

confirmed. There is then a list of lands given some half way

through which is the statement:

...and of Glympton from the

fee and gift of Geoffrey Clinton, as contained in the charters of the

same, with all the appurtenances and liberties which the aforesaid

lands and churches he had better and more fully in the time of King

Henry my grandfather.... Also the manor of Packington (Pachinton)

with all its appurtenances and liberties, by the gift of Geoffrey

Clinton and the grant of Henry Arden and Hugh his brother, by the

service of half a knight...

There was then listed the land of Bretford given by the nuns Seburae

and Noemi and the concession of the same Geoffrey Clinton. It is

quite obvious from this charter that King Henry II

(1154-89) was expunging the actions of Geoffrey in founding Kenilworth

priory and consequently upgrading the monastery to a royal

foundation. No doubt this was due to King Henry II have reclaimed the royal land of Kenilworth with its castle back into the state it was during the reign of Henry I (1100-35). This was Henry's main policy on acquiring the English kingdom in 1154.

Geoffrey Clinton Junior (d.1169/75) also made a charter to Kenilworth

priory. In this he conceded all the lands, churches and other

things given by his father:

Firstly, namely all the land

of Kenilworth itself in the forest and the plain, and all the other

belongings of the aforesaid vill, with the exception of the particulars

which my same father retained therefrom to make his castle and

park... In addition, a full tithe of everything that has reached

Kenilworth castle, whether to the cellar or to the halgard, both from

purchases and donations, as well as from their own rents; that is to

say, in wheat and hay... and in all other things whatever and however

they reached Kenilworth castle, although all these were also tithed

elsewhere. Moreover, in any one week, the canons are to have one

day of fishing in the castle vivarium on any one day they choose...

Henry Clinton (d.1216/18), Geoffrey Junior's son, of course mentioned

nothing of Kenilworth castle, but obviously did still hold some rights

in the vill. One of his probably twelfth century charters to

Kenilworth priory, expanding an earlier grant by his father, Geoffrey

(d.1169/75), referred to his land:

on Dedecherleshull and all the moor from the bridge of Redfern (Wridefen) beside the road to Coleshill as far a the assart of Renald Halfcherl of Redfern.

The text of these charters suggest that Geoffrey Clinton (d.1131/33)

retained the south and west part of the land of Kenilworth for his

castle and park, while the eastern part went to the Augustinian priory

whose canons were given permission to fish in the mere and graze their

livestock in the park. The original charters mention the 6 lands

held by Geoffrey and granted to the priory. The most important of

these was undoubtedly Kenilworth. At Domesday in 1086 Kenilworth (Chinewrde)

had been unvalued, but consisted of 3 virgates of royal land held by

Richard the Forester. In this land were 10 villagers and 7

smallholders with 3 ploughs. It's forest was ½ league long

by 4 furlongs wide and it all lay in the royal manor of

Stoneleigh. Quite obviously at some point before 1125, King Henry I

had granted the land of Kenilworth to his chamberlain, Geoffrey

Clinton. Geoffrey then began the great castle here, rather than

in his main family estate. Geoffrey's origin is shown in one of

his grants to Kenilworth priory where he gave the church of Clintona,

the place his family takes its name from. This is now known as

Glympton in Oxfordshire and gives the lie to the idea that Geoffrey was

raised from the dust. It would seem likely that his father was

the William who held Glympton from Bishop Geoffrey of Coutances in

1086. William, assuming he is the same man, also held - amongst

the other 289 manors held by otherwise unidentified Williams - 2 other

places later held by the Clintons, namely, Baddesley Clinton and

Wormleighton in Warwickshire. This is probably the best

indication that this William's known descendants took the name Clinton

from the present day Glympton.

William would seem to have had at least 2 sons, possibly the elder,

Geoffrey (d.1131/33) and also William (d.1136+). Geoffrey began

witnessing documents for King Henry I

from at least 1108 and this he continued to do until his death in or a

little before 1133. The bulk of these documents occur after the

Welsh campaign of 1121 and taken together they tend to show that

Geoffrey was often in the court of Henry I both in England and not so

often in Normandy. It also shows that although his brother,

William Clinton, witnessed at least 4 documents for King Henry I,

he was by no means as popular as his brother. Despite this favour

shown to Geoffrey, it is probably only in the period 1121-23 that he

was made sheriff of Warwickshire as is evidenced by the precept of the

king to him made at Woodstock in that period.

The 1130 pipe roll allows some of the Clinton lands to be

unravelled. In Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Geoffrey was

pardoned Danegeld for £7 9d which William Pont de l'Arche ought

to have paid. Presumably this was the chamberlain, William Pont

de l'Arche (d.1152) of Portchester castle.

Why Geoffrey was holding any of his lands is unknown, although it is

possible that there was a marriage link here and Geoffrey's wife,

Lesceline, was in fact William's daughter. Elsewhere in

Nottinghamshire Geoffrey is pardoned a further Danegeld assessment of

57s 8d and a borough assessment of 28s 10d. He was also pardoned

8s Danegeld in Wiltshire; 2s 8d in Northumberland; 48s 8d in Hampshire;

10s in Cambridgeshire; 24s 9d in Sussex; 40s 3d, 7s 2d and £4 5s

in Leicestershire; £7 12s in Buckinghamshire; £16 15s 3d in

Warwickshire; £4 12d in Berkshire; £11 10s in Windsor and

5s in Rutland. It is noticeable that no Clinton holdings seem to

have survived in Wiltshire, Northumberland, Hampshire, Cambridgeshire,

Sussex, Berkshire, Windsor or Rutland. Perhaps most of these

lands were held at the king's pleasure rather than in fee.

Alternatively all these lands were seized back by Henry II (1154-89) early in his reign.

Perhaps Geoffrey's accounting skills were not too great for in

Hampshire it was noted that he owed £9 11s 8d ‘for a

deficit in treasure whilst he was with Robert Mauduit in

Normandy'. He also owed 80m (£53 6s 8d) in Northamptonshire

for having custody of the son of William Diva and his land, as well as

50m (£33 6s 8d) for Richard Martinvaus having half the land of

Norman his uncle. Geoffrey was also sheriff of Warwickshire at

this time. His accounts show him £32 9s 4d in arrears for

the old farm of the county as well as owing 310m (£206 13s 4d)

for having the office of treasurer of Winchester,

of which he paid 100m (£66 13s 4d) this year. Other debts

he had run up included grants of lands, pledges, farms, as well as for

a charter confirming what the earl of Warwick had given to Geoffrey's

church of Arden. Presumably this church was Kenilworth which lies

roughly centrally in the old district of Arden. That district ran

roughly from Stratford on Avon in the south to Tamworth

in the north. Geoffrey's brother William was also active in the

pipe roll, paying 20m (£13 6s 8d) in Buckinghamshire of a 145m

(£96 13s 4d) debt for the land which Ralph Fitz Turstin [possibly

otherwise known as Ralph Wigmore] took with his wife in Normandy.

Geoffrey Clinton was dead by August 1133 when King Henry I,

soon after July 1131, was at Beckenham when he issued a notification

informing Bishop Roger Clinton of Chester (1128-48) and Nicholas

Stafford (d.1138) and the men of Staffordshire that a final concord had

been made between the prior of Kenilworth and Hugh, the king's watchman

concerning the lands which were the inheritance of Hugh's wife.

By this agreement Kenilworth priory was to have Stone (Stanis) church and Brusard's land that went with it, with half the wood and the land of Alan the son in law of Anisanus in Colwalton (Waletone)

etc... Further all these lands were to be held directly from

Geoffrey, the son of Geoffrey Clinton, to whose fee they

belonged. Hugh was to have the rest of the [unnamed]

inheritance. Amongst the witnesses to this charter was William

Clinton, the brother of the elder Geoffrey. That William survived

his brother is confirmed by a precept of 1130-35 by which King Henry I notified William Clinton that the king's men of Stonleigh

were to have their pasture in the hay that the king had given to

Geoffrey Clinton as they had done in Geoffrey's time and as it was

agreed when the king gave the wood. That William Clinton was

uncle to the younger Geoffrey is confirmed by Geofrey's confirmation of

the grant of his uncle, William Clinton, of Cassington (Chersintona, some 6 miles south of Glympton), to Eynsham abbey before 1152.

The Clintons had also acquired estates in Normandy, for in October

1154, Geoffrey Clinton (d.1169/75) recognised that his land of Douvres

in Calvados had been mortgaged to Bishop Philip of Bayeux for £30

Tours and that Conion

would remain to the treasurer of Bayeux as had been quitclaimed in the

year that the duke of Normandy made a peace of 3 years with the kingdom

of France.

In 1166, it was recorded that Geoffrey Clinton held 17 fees of Earl

William of Warwick (d.1184). Some of these fees are those that

were granted to Kenilworth priory. One of them was probably

Coleshill which Geoffrey sold to his cousin, Osbert, who thereby

founded the Clinton of Coleshill line. Elsewhere Geoffrey had

held 5 fees of Earl William of Gloucester (d.1183), but these were now

merely marked in the earl's charter as the fee that was Geoffrey

Clinton's. For what reason Geoffrey was deprived of these fees

before 1166 is unknown, but possibly he was incapacitated or in

disfavour during the writing of the charter. His son and heir,

Henry Clinton (d.1216/18), certainly held at least 1 fee of the earldom

of Gloucester as late as 1210. Regardless of events in 1166,

Geoffrey the Chamberlain of Glympton (Glint') was elsewhere recorded as holding a fee of Robert Scrope (d.bef.1190) and 3 of the honour of Wallingford,

the old barony of Brain Fitz Count (d.1147/51). Finally, Geoffrey

the chamberlain held 2 fees of Earl William Ferrers (d.1190), one of

which was held by Robert Fitz Ralph and the other by Peter Goldington.

Oddly the Clintons do not appear much in the royal records of Henry II.

Osbert Clinton (d.1200) was paying his taxes in Coleshill during

1165. However, his probable uncle, Hugh Clinton (d.1169/75), was

forced in 1166 to make of fine of 20m (£13 6s 8d) in Shropshire

for the evil words he had said against the king. This possibly

reflected the general Clinton feeling about their monarch, for the

family certainly was not as powerful or influential as it had been

under Henry I (1100-35).

The younger Geoffrey Clinton seems to have died in or soon after

1169. That year is the earliest possible date for one of his

charters to Kenilworth priory. It was not until 1175/6 that his

son, Henry Clinton (d.1216/18), gained some of his father's lands back,

namely a fee held of the earl Ferrers and ‘his right' in

Warwickshire with half a fee in the same county. For these rights

he pledged the 3 sums of £5, 20m (£13 6s 8d) and

£5. These amounts obviously did not include a fine for the

castle of Kenilworth and the bulk of Geoffrey Clinton's old

barony. The usual inheritance fee for such a barony with a castle

on the scale of Kenilworth would more likely have been

£100. In any case, from 1173 onwards Kenilworth appeared as

a royal fortress. Further, Henry Clinton did not pay his £5

fine for half a fee that he had not yet had. No doubt at this

time, Kenilworth was held by the sheriff of Warwick for Henry II

(1154-89). In addition, Henry Clinton may have been under age

after the death of his father. What is certain is that for some

reason, probably after the younger Geoffrey Clinton's death soon after

1169, the king did not return the fortress to Geoffrey's heir.

King Henry certainly had a dislike for Henry's probable cousin, Jordan

Clinton (d.1187). He was fined the large amount, for such a lowly

person, of £100 for his misdeeds in the 1173-74 rebellion.

What has been missed in all this, is where is Geoffrey Clinton's carta

of 1166? All tenants in chief are mean to have made one and the

great majority of them did. The answer to this seems to be that

Geoffrey was already in disgrace or exile. His mention in other

barons' cartae shows that he was alive at this time, as does his making

a charter to Kenilworth priory soon after 1169 at the earliest.

The final piece to this historical jigsaw seems to be the fact that Henry II was treating Kenilworth hay as his own property in 1165. It therefore becomes obvious that Geoffrey had fallen foul of Henry II

in some fashion and had lost Kenilworth castle by that date. The

same year, 1165, the king received 10s from the sheriff of Warwickshire

for the chattels of ‘some fugitives from Kenilworth'.

Kenilworth castle was obviously both functional and in the king's hands

during 1173 as he spent £8 6s 8d in munitioning it with 100 loads

of grain, 20 loads of beer (brasii)

at 33s 4d, 100 bacons at £7 10s, 40 salted cows at £4, 120

cheeses at 40s and 25 loads of salt at 30s. Also £5 was

spent on Kenilworth (Kinildewurda)

jail. This was mostly likely within the castle. The

garrison of the fortress was at this time increased by a horse sergeant

and 64 foot sergeants at a cost of 66s for a 20 day stay. The

pipe roll also shows that the motte of Warwick castle

was munitioned at the same time. During the next year up to

October 1174, more money was spent on both castles. Kenilworth

gained 10 horse sergeants for 77 days at £11 3s 4d and certain

knights at a cost of £33 6s 8d. There was a further knight

with foot sergeants at the castle who received £11, before a

further £180 41s 8d was spent on another 20 knights and 140 foot

sergeants for 115 days. Quite possibly another force also briefly

resided at the castle as another 27s 6d was accounted for the cost of

‘the knight and sergeants of Kenilworth'. Finally, there

was recorded another payment for £132 19s 2d for ‘the

knights and sergeants of Kenilworth'. Quite clearly Kenilworth

was a large fortress to support such a garrison and it played an

important role in suppressing the rebellion of Earl Robert of Leicester

(d.1190).

The fate of Kenilworth castle before this time seems to be explained by a copy of a later charter. This shows that King Henry II

had simply exchanged Kenilworth castle for lands elsewhere.

Thereby appropriating the fortress for his own use in the 1170s.

In the early years of the reign of King John

(1199-1216), Henry Clinton (d.1216/18) made a charter to John

quitclaiming all his rights to Kenilworth castle and all its

appurtenances just as King Henry II

had held seisin of it on the day he died in 1189. Another survey

from 1242/43 states that the abbot of Woburn held 4½ hides in

Swanbourne Inferior of the king; lands which had been exchanged with

the king for Kenilworth castle. As late as 1274 Swanbourne,

Buckinghamshire, consisting of 13 hides held by Woburn, was reckoned to

be partially held of the honour of the Earl Marshall and partially of

the honour of Clinton. Indeed, as early as 1179, Henry Clinton

was litigating against Ralph Caisneto over half a fee in Swanbourne (Suinburna).

It is reasonably clear from this that the ‘exchange' had already

taken place by 1179. Similarly, Henry was paying a fine made in

Warwickshire to have his lands in 1176 and 1177. The fact that

Henry only appeared in the pipe rolls from 1175 when he was using legal

methods to obtain lands would suggest that he had only come of age

around the time of the 1173-74 war and that his estates had been held

by others during his minority, obviously with disastrous effect for the

Clinton barony.

From this it is quite clear that the order of the king's government on

17 March 1218, that the sheriff of Warwickshire was to return to Henry

Clinton full seisin of his rightful hereditary lands without delay and

that this included ‘the right and inheritance of Henry his

father, whose heir he is in Kenilworth, which you took into your

hand...', was never implemented. Certainly the castle remained

under royal control and in any case Henry died probably before 1231

when Lavendon castle, which

honour his father had been holding since at least 1193 and in 1201 was

accounted as one of his fees, appeared to be lordless. On Henry's

demise his remaining lands were divided amongst the heirs of his 3

sisters, what was left of the barony itself going into abeyance.

Quite clearly Kenilworth castle was from before 1173 maintained as a

royal fortress and at the king's expense. In 1181 the sheriff of

Warwickshire paid 27s (3 lots of 9s) into the royal coffers for his

farm of those dwelling within the enclosure of Kenilworth castle (de firma commorantium in clauso castelli de Kenillewurda).

This farm then became a regular payment into the Exchequer, the next

year the 9s being paid ‘from the land which is enclosed in

Kenilworth castle'. By 1200 the amount had risen to 10s per annum

and by 1206 it was dropped to 3s for the enclosure (de clauso)

of Kenilworth. In the meantime work had gone on at the

fortress. In September 1184 it was recorded that £26 9s 9d

had been spent in repairing the castle walls by the view of Geoffrey

Corbecun and Henry Ponte. Further works were carried out in

repairing the tower, castle and houses of Kenilworth for Richard I

(1189-99) in 1190 at a cost of £46 7s by the view of Robert and

Walter Stanley. The work continued into 1191 when a further

£12 10s was spent on the works and munitioning of the fortress by

the view of William Brown and William the Falcolner. During the

emergency after the capture of the king by the Germans in 1193, further

works cost 66s 11d at the view of Richard Malherb and [William]

Brown. A garrison of 5 knights was also placed within the

fortress for a period of 40 days.

During the early years of Richard I

(1189-99), Bishop Hugh of Coventry, as sheriff of Warwickshire,

accounted for £20 for keeping the 4 castles of Kenilworth, Mountsorrel, Newcastle under Lyme and Tamworth. Hugh Bardolf also received 26s 5d for his custody of Kenilworth and Mountsorrel

castles. Further, Hugh received another 27s 10d and 26s 5d in

1191, while 20 horse sergeants and 100 foot sergeants were stationed

within both fortresses at a cost of £32 11s. Under King John

(1199-1216) the castle was largely neglected with the constable, Hugh

Bardolf, being replaced by Hugh Chaucumb on 23 October 1203. Hugh

in turn was superceded by Robert Roppell on 13 July 1207.

During this time some work was done at Kenilworth and the king visited

on 5 known occasions, 11 August 1204, 17 March 1205, 18 July 1209, 22

November 1212 and 3 April 1215. In 1201 work on the castle

amounted to just £2. While in 1206, £17 was spent on

works on the castle and a further £5 on repairs. The real

refurbishment of the castle only began in 1211 when the king spent

£361 7s on castle work at Kenilworth. The same year he

spent £102 19s 3½d on the work of the chamber and

garderobe. Presuming, as is natural, that this chamber and

garderobe were within the fortress, this made a grand total of

£464 6s 3½d spent on castle work. The next year by

September 1212, £224 17s 8d, had been expended on the fortress by

the view of Geoffrey Jordan, clerk and Geoffrey Cropisalt. As the

king himself was at Kenilworth castle on 22 November 1212, it is to be

presumed that he had arrived to view what his £689 3s 11½d

had bought him for what had become one of his most favoured fortresses.

There are no surviving royal accounts for 1213 or 1216, but King John's

visit of 1212 may suggest that work was finished on Kenilworth

castle. Whatever the case, on 30 September 1213, William

Cantilupe (d.1239) was ordered to free William Pantulf and Geoffrey

Keteleby from custody in Kenilworth castle as they had made a fine for

their release. The next year on 22 April 1214, William Cantilupe

(d.1239) was ordered to set free a further 2 prisoners from

Kenilworth. It can therefore be seen that Kenilworth was at this

time one of the most secure castles in England and consequently, along

with Corfe and Windsor, used as a royal prison. Everything

changed with the barons' revolt of 1215. On 3 April of that year,

the king was found at Kenilworth, before moving on to Woodstock, 35

miles away, the next day. By May John was brought to terms at

Runneymede and on 15 June 1215, he made the constables of Northampton,

Kenilworth, Nottingham and Scarborough

castles swear to obey the council of 25 barons as security for the

execution of Magna Carta. By this action he apparently alienated

control of these fortresses. It is also evident that these 4

castles had earlier been appropriated by King Henry II

(1154-89). Henry had apparently seized Northampton from the

Senlis earls before 1173, Kenilworth from the Clintons around the same

time and Nottingham and Scarborough from the Peverels and Earl William

of York at the end of the Anarchy (1136-54).

Despite King John's show of good

faith by making this offer of the castles, the rebels were not

placated. By the end of August 1215 they had again defied the

king and on 5 September were excommunicated. The result was the

king's attack on Rochester castle that autumn. It is to be

presumed that royal control of Kenilworth castle was restored about the

same time as that September £402 2s was accounted in the pipe

roll for its repair. Henry Clinton's death around this time could

therefore quite possibly be associated with the return of Kenilworth

castle to royal control. Interestingly, one of the instruments of

Magna Carta was that the king would immediately restore all the lands,

castles, liberties and rights to anyone who had lost them (suorum, de terris, castellis, libertatibus vel jure suo, statim ea ei restituemus).

Quite obviously Kenilworth might be seen as high on such a list,

especially when the terms of Henry Clinton (d.1231) coming to the

king's peace in 1217 are considered. These are discussed below.

Rochester castle was besieged by King John

on 11 October 1215 and fell 7 weeks later on 30 November.

Presumably Kenilworth had changed hands earlier, or the accounting

period for the year ending 29 September 1215 fell far later than

normal. In any case, Kenilworth is next seen under royal control,

if it had ever truly been lost. The baronial attack on

Northampton castle - another pledge castle - in May 1215 failed.

Certainly the expenditure of over £400 on repairs recorded in the

Michaelmas 1215 accounts at Kenilworth suggests heavy damage to the

castle. Sadly the chroniclers of the age were all fixated on the

king's personal siege of Rochester castle and the changing of control

of many castles elsewhere were simply not thought worthy of much

comment, cf. Bedford castle. On 13 December 1215, prisoners from

the fall of Rochester castle were distributed to various castles, one

of which was Kenilworth. By 19 June 1216, Ralph Normanville was

constable of Kenilworth, when he was ordered to be intendant upon

William Cantilupe. The same day the king made provision for his

son [Henry] who would join Ralph in Kenilworth castle, his other son,

Richard going to Wallingford. This strongly shows the king's

appreciation of the castle's strength and security. By the time

of John's death Henry was in Devizes castle in the more secure South

West of England.

What then can be made of these events? Firstly, although it is often stated that King John

spent between £1,000 and £2,000 on ‘the fortification

of a castle whose defences were already formidable', it is clear that

this is simply not true. Similarly, there is no evidence that a

sum of money claimed to be £1,100 was used for

‘strengthening Kenilworth with curtain walls and towers, and

improving it with work on a dam and possibly the domestic

accommodation' under King John.

As has been seen above, the only things actually mentioned as being

built at Kenilworth are the chamber and garderobe and these are not

specifically mentioned as being at the castle and indeed are in a

separate account to the castle works. What we do know is that the

considerable sum of £689 3s 11½d had been spent on work at

the castle and a chamber and garderobe between 1211 and 1212 [more may

have been spent on the castle in 1213 as the accounts for this year are

missing], while a further £402 2s had been spent in repairing the

castle in 1215. Now it is possible that the scribe wrongly put

repair instead of work in the latter case, but that cannot be simply

assumed. Usually the scribes knew what money was spent on as that

was the whole point of keeping accounts. However, as the account

of Philip Marc in the 1214 pipe roll is thought to date from the

minority of Henry III, perhaps

as late as 1220, it is equally possible that the repairs accounted for

at Kenilworth date to a time some years after the traditional ending of

the Michaelmas accounting period on 29 September 1215.

The idea that the castle may have been attacked in 1215 is somewhat

strengthened by the fact that one of it's towers fell down over

Christmas 1218 and had to be rebuilt by Constable William Cantilupe at

a cost of £150 2s 3d. The order for this was sent out on 7

July 1220 and the costs appeared that Michaelmas. In 1221 an

expenditure of £5 was authorised on the castle for its amendment (emendatione).

Similar amounts were regularly allowed for the amendment of other royal

castles, particularly Carlisle on the Scottish border. This trend

continued in 1222 and onwards until 1224. This was obviously an

amount to be used yearly, for in 1223 a further £17 6s 8d was

used for work at and repair on the fortress, while the normal £5

was recorded beneath as being used for amendments to the hall.

Despite this, the £5 expenditure for 1224 does not seem to have

been recorded, though 42s was recorded for carrying 5 tuns of wine from

Southampton to Kenilworth. In 1226 it was accounted that 14s had

been spent on amendments to the gaol and castle of Kenilworth.

The next year, 1227, saw no pipe roll for Warwickshire, but in 1228,

£10 was spent on amending the houses in Kenilworth castle.

Presumably this included the £5 from both years. In 1229,

the standard £5 was recorded against the amending of houses

within the castles, while a further 5½m (£3 13s 4d) was

spent on the fishery. The year 1230 saw the standard £5

accounted for amending the castle houses, while 20m (£13 6s 8d)

was also spent in repairing a broken (brecke)

turret of the fortress. Once more £5 was accounted for

amending the houses of the castle in 1231, but this was the last

occasion on which such a sum was recorded against Kenilworth castle.

In 1232 the keep was repaired using lead, wood and stones at a cost of

£32 by the view and testimony of John Baiocis and Geoffrey Bosse,

while in 1233, amendments were made to the houses in Kenilworth castle

for 15s. Between these 2 events, the king had stayed at

Kenilworth on 24 November 1233. The year 1234, saw a new oriel

built before the entrance to the king's chamber for £6 16s 4d,

while repairs to the fishery cost £4 10s 6d and amendments to the

king's houses within the castle were accounted for at 46s 7d. The

fishery was repaired again in 1235 and in 1236 £4 was spent on

amending the castle houses. On 18 March 1238, the king ordered

the custodian of Kenilworth castle, Hugh le Poer, to deliver it without

dely to the archbishop of York for the use of the papal legate at

pleasure. Presumably the legate had had his pleasure by 14 to 16

September 1238, when the king himself stayed at Kenilworth.

Before this, while Simon Montfort (d.1265) was in Rome, his Countess

Eleanor (d.1275), the sister of King Henry III,

dwelt in Kenilworth castle, apparently from March until 14 October

1238. It seems likely that Simon and Eleanor remained at the

castle on his return, for their son, Henry (d.1265), was born there on

28 November 1238. Henry was to die beside his father at the

battle of Evesham 26 years later.

No doubt due to his September sojourn at Kenilworth, the king ordered

repairs to the fortress. These took the form of reroofing the

houses at a cost of £14 15s ½d. King Henry III appears to have had something in mind for Kenilworth for on 26 February 1241, he ordered the sheriff of Warwick to:

cause the chapel in the king's castle of Kenilworth to be wainscotted, whitened and painted (lambricscari, dealbari et depingi);

a striped wooden wall to be made to separate the chancel from the body

of the chapel; 2 seats to be made of wood, one for the king on the

south side and one for the queen on the north side, suitably painted; a

suitable painted seat to be made for the queen in the chapel in the

tower of the castle and the porch of the tower, which has fallen, to be

rebuilt; a roof to be placed on the great chamber which is unroofed;

the gaol with the brattishing in which the king's bells hang to be

repaired; all gutters to be repaired where necessary; as much as shall

be found necessary of the wall of the castle, which threatens to fall

into the fishery, to be pulled down and rebuilt; all costs to be

credited by the view and testimony of lawful men.

The king returned to stay at Kenilworth on 11 September 1241.

Apparently what he found was not satisfactory for the same day he

ordered the sheriff of Warwick to:

cause the queen's chamber in

Kenilworth castle to be wainscotted, whitened and painted and the

windows broken and made larger; to have the fireplaces (caminos) of the

king's and queen's chambers repaired; a privy chamber by the queen's

chamber and the castle wall repaired; the 2 gates of the castle to be

likewise repaired; a new wall to be built between the inner and outer

wall of the castle, a new porch with a finial (crappa)

to be made before the queen's chamber and a window to be made on the

north side of the castle chapel as well as a swing bridge, the cost to

be credited by view.

This all seems to have been rapidly put in hand if it was not finished, for, allegedly by Michaelmas 1241, the sheriff recorded:

that the chapel of Kenilworth

castle was to be plastered and painted, also the wooden wall in the

same was to be made as well as 2 (wooden) seats in the same for the

king and queen which were decently painted; also the chapel tower in

the castle which had been destroyed is to be rebuilt and the great

chamber in the same castle is to be reroofed; and the gaol there with

its brattishing on which they all depend is to be repaired, also the

guttering there; the outer wall to the south above the fishery is to be

thrown down and rebuilt where necessary; also the king's chamber is to

be plastered and limed, with the windows of the same chamber knocked

out and made larger; also the king's and queen's chambers were repaired

and a certain private chamber made next to the queen's chamber; also a

certain new chamber was made in the bailey towards the fishery; and to

support that with pillars of stone and to repair the walls of the

castle itself; and for repairing the 2 gates there; also to make the

wall between the inner and outer wall of the same castle; also a new

porch before the queen's chamber with a certain finial (trappa)

made; also a new window in the king's chapel on the north side and a

turning bridge were to be made for £113 8s ½d by the view

and testament of Hugh le Jounne and Alexander Wudecote.

The supporting of the castle walls ‘with pillars of stone',

strongly suggests that some buttressing was applied to the outer

curtain walls at this time. Previously these have been thought to

be fourteenth century as they are elaborate structures and have fine

plinths. However some of them are plain and it is quite possible

that they are a hundred years older and that the outer ward to the

west, traditionally built by Henry III, is in fact the work of King John in 1211-12 and needed buttressing in 1241.

During 1241 the sheriff also accounted for 4 Welsh hostages and 2

custodians living at the castle at 2d per day for 23 weeks and 4 days,

costing £8 5s. The next year it was recorded on 7 April

1242, that the king acknowledged that Gilbert Segrave had received the

royal castle of Kenilworth to keep during pleasure on condition that he

will surrender it to no one but the king himself during his lifetime

and to the queen for the use of their heir after the king's

death. Further, if she could not come personally to the castle,

Segrave was only to surrender it to one of the queen's uncles not in

the fealty of the king of France. To this Gilbert had sworn on

the holy gospels before the king. Similar ceremonies were enacted

for the constables of Dover, Canterbury, Rochester, Hertford and

Colchester castles. Less than 2 years later on 18 February 1244,

the king granted Earl Simon Montfort (d.1265) custody of Kenilworth

castle after having Gilbert Segrave surrender the fortress back to

him. Then on 9 January 1248, he appointed his sister, Simon's

wife, Countess Eleanor of Leicester (d.1275), to hold Odiham manor

during pleasure together with Kenilworth castle. Despite this,

the king was still sending orders to ‘the constable of the king's

castle of Kenilworth' to cut back the woods to clear robbers from the

district. Three years later the grant of Kenilworth to the

Leicesters was converted to one for both their lives in November

1253. In 1265 the earldom of Leicester, of which Kenilworth was

apparently now seen as a member, was said to be worth £400pa.

During the Mad Parliament of Oxford in the Spring of 1258, Earl Simon

Montfort freely returned his castles of Kenilworth and Odiham to the

king, in making amends for complaints raised against the king by the

barons of wasting his royal inheritance. Other barons, like

William Valance (d.1295), refused to surrender other royal castles left

to Henry by his father, King John,

and subsequently frittered away by him. Presumably the king

subsequently regranted Kenilworth back to Earl Simon. The king

soon found the opportunity to regret his generosity as just a few years

later Simon used this great castle in his war against his king.

During the opening stages of the civil war Simon certainly spent some

time at his great castle and moved from there against London in the

autumn of 1263. He later left Kenilworth for France in December

1263, but, after a fall from his horse broke his tibia, he retired on

Kenilworth and ran the war from there during the early part of

1264. That March the baronial army formed at Kenilworth and again

prepared to march on London. The same week that Simon left

Kenilworth:

John Giffard (of Brimpsfield,

d.1299)... was deputed with others to guard Kenilworth castle, a

wonderful structure which the earl of Leicester had strengthened by

repair and by various machines which we had not heard of until now and

wonderfully equipped it with men. They captured Warwick castle

with its earl, William Maudut, who, because of his recent conversion

had been suspected of being for the king and brought him with his wife

and family a prisoner, to Kenilworth castle. They overthrow

Warwick castle, lest the royalists should have a refuge there.

After the king's defeat at Lewes on 14 May 1264, Kenilworth also became the prison of the king himself, his son, Lord Edward

(d.1307) and his uncle, King Richard of the Romans (d.1272). The

latter 2 were brought there again in December 1264 after a failed

rescue attempt had nearly reached them at Wallingford castle.

After Edward escaped his captors, the war progressed with Kenilworth

becoming a main centre for the rallying of baronial forces. On 16

July 1265, the army of Simon Montfort Junior (d.1271) abandoned the

siege of Pevensey castle and marched via Winchester, Oxford and

Northampton to reach Kenilworth on the evening of 31 July. From

Kenilworth Simon proposed to go to the relief of his father and Henry III

in the Welsh Marches. This baronial force did not set up guards,

but unwisely bivouacked outside the castle. As a result, the Lord

Edward, operating from Worcester, fell upon Simon's forces after a

night ride, on the morning of 1 August and shattered them, capturing

many of the leaders in their beds in the priory. These were

experienced soldiers like Earl Robert Vere of Oxford (d.1296), William

Montchesney (d.1287), Baldwin Wake (d.1282), Richard Grey (d.1298),

Adam Neufmarche and Walter Coleville (Bytham, d.1277). At the

same time many lesser men were slaughtered. The young Simon

Montfort with only a few men fled into the castle as his army was

destroyed.

Due to the defeat of the young Simon, Prince Edward was allowed to

sweep down on his father, who was with Earl Simon and destroy the earl

and his army at the battle of Evesham on 4 August 1265. In this

action Earl Simon refused to abandon his infantry and flee to the

safety of Kenilworth castle, bringing death upon himself and most of

his knights. In the aftermath of the battle, the Lord Edward wrote from Chester on 24 August 1265, explaining that:

since there are some of those

in Kenilworth castle whom we can and must rightly regard as our

enemies, it is deemed equally expedient to write to them on the part of

our aforesaid lord [Henry III], that if they do not want to be regarded

as public enemies and be disinherited and lose their lives, as they

have deserved, to let them commit and assign the said castle without

delay to any of our lords...

Those named as in the garrison under John Muscegros (d.1266) were 10

knights and 14 sergeants, 2 of whom were clerks. Consequently

such a note was to be written to them and carried by a messenger under

religious orders (ie. who was therefore supposed to be neutral in

worldly matters and a good idea when considering what happened to a

later messenger) explaining:

How lately at Evesham by

divine clemency the king obtained victory and triumph over his many

enemies opposing him in many ways... And although the king ought

to deal with them, generally and severally, judicially rather than

mercifully, yet, of his inborn benevolence he has thought fit to

counsel them, commanding them, as they would not be reputed public

enemies, or be disinherited or lose their lives, as lately their

accomplices deservedly did, that they should go out of the said castle

and deliver it to the king without delay.

The message is not known to have made any affect upon the

garrison. However, Simon Montfort (d.1271), who was within the

fortress around this time, did wish to make his peace.

Accordingly on 6 September, his Kenilworth prisoner, King Richard of

the Romans (d.1270), who also happened to be Simon's uncle, was with

Simon Junior in Kenilworth priory when Richard swore to do his best,

saving his fealty to King Henry III,

to be a loyal friend of his sister, Countess Eleanor of Leicester and

all her children. She was at the time in Dover castle with her

younger children. With this Richard was released and Simon

himself went to the Winchester parliament that September, where he

found the king's terms for his surrender too harsh. He therefore

returned to Kenilworth and prepared for further resistence.

In early December 1265, the government began planning for a great siege

of Kenilworth to begin on 13 December with the feudal host for this

forming at Northampton, 30 miles from their target. Around the

same time Simon Montfort left Kenilworth well garrisoned and set about

the country raising discontent and new forces to oppose Henry III

in the Fenlands. This attempt proved unsatisfactory for him and

around Christmas he surrendered to the king on the terms that he should

surrender the earldom of Leicester with Kenilworth and receive a yearly

pension of 500m (£333 6s 8d) in return. However, Simon

later fled from the Lord Edward's

company in the Tower of London to France around the second week of

January 1266. Despite this, the garrison of Kenilworth kept up

its opposition, stating to the king that they had been ordered to hold

the fortress and still did for Simon and his mother. And so:

They immediately raised the

standard of Simon the Younger, who was staying in France, proclaiming

him lord and heir of that castle.

The garrison occupied the passing months by riding out each day and

seizing what they needed from the surrounding districts, despite the

opposition of Prince Edmund (d.1296) who endeavoured, sometimes

successfully, to oppose their raids. Certainly on 1 February

1266, the king wrote that the rebels holding out in Kenilworth castle

were attacking Worcestershire causing homicides and other grievous

offences in throwing down, burning and devastating castles and houses

of the king's faithful subjects.

On 15 March 1266, the king ordered his sheriffs to form their levies at

Oxford at Easter (17 April) to attack the castle after one of his

messengers to the fortress had been deliberately mutilated. The

king arrived in person at Oxford on 20 April and moved into the castle

there, which lay 44 miles from Kenilworth. A week later

sufficient troops had arrived to march against Kenilworth castle and on

27 April the king left with his troops for Northampton, 38 miles away,

apparently intending to go from there to Kenilworth - another 30 mile

march. Yet after he left Oxford the city was attacked, presumably

by troops from Kenilworth. Consequently the march to Kenilworth

never took place. Instead the Lord Edward

took Lincoln, while his brother, Prince Edmund (d.1296) won the battle

of Chesterfield on 15 May 1266. This was at a time when it was

thought that Simon Montfort (d.1271) had formed a new army to invade

England. This army was apparently still loitering on the French

coast on 15 September 1266, when the pope ordered King Louis (d.1270)

not to give aid to ‘the relict of Simon Montfort or her son,

Simon, to attempt by means of his [French] subjects, to recover the

property which the said earl had most justly lost'. Regardless of

the actions of the Montforts, after the barons' defeat at the battle of

Chesterfield on 15 May, one of their leaders, Henry Hastings (d.1268),

fled the field and found sanctuary in Kenilworth castle.

Meanwhile, Simon himself allowed King Louis of France (d.1270) to

negotiate on his behalf with an obdurate King Henry III. In the end Simon left to campaign with Charles of Anjou (d.1285) in Italy.

With these victories a new royal muster was ordered against Kenilworth

and on 24 June the king and Lord Edward arrived before the castle with

an army which had marched from Warwick which lay less than 5 miles from

the fortress. However, some of the garrison counterattacked the

same day and drove a portion of the army all the way back to

Warwick. By this time the Kenilworth garrison seems to have

consisted of over 1,200 combatants. The Dunstable priory

chronicle stated that they consisted of 1,700 men bearing arms

[presumably mounted knights and serjeants] and 28 women, with an

unknown number of infantry, while Rishanger heard of a garrison of over

1,200 men with their wives and maidservants numbering 54. In

reply the royalist attackers split their forces into 4 camps, one under

the king, one under the Lord Edward,

one under Roger Mortimer of Wigmore (d.1282) and one under Prince

Edmund (d.1296). The attackers then set up 9 siege engines called

Blidis. This word seems

to originate from Byzantine Greek and had been used to mean catapult in

England since the early thirteenth century and could also describe

trebuchets. It seems likely that these weapons were only

catapults as, although they continuously launched stones at the castle

breaking down the wooden houses and towers, they were unable to smash

down the main castle defences made of stone. Possibly it was

difficult to get the weapons in good attacking sites for some of the

defenders held positions outside the castle gates and from there

advanced on their enemies many times, killing several of the king's men

with arrows, lances and swords, with the result that the king and the

Lord Edward and their men, remained permanently at arms through fear of

such attacks. Despite this, the attackers seem to have made no

attempt to break into the castle by assault. Instead they decided

to wait for starvation to deal with the fortress. The Oxford

chronicler noted that the attackers:

came from every direction, with many kinds of machinery, attacking the enclosed multitude in every way that could be devised.

While a contemporary recorder of the war found that:

Prince Edmund, the king's

son, prepared with great energy a wooden tower, very sumptuous,

surprising in height and width, which was fitted to the wall by

ingenuity, in which were placed in compartments 200 crossbowmen and

more, so that through the shootings of weapons and arrows, the garrison

would incur losses. But the defenders positioned a mangonel which

did not stop shooting until it had earned constant hits, the

reverberation, penetrating and collapsing it. There was also

another device exceedingly admirable on the part of the king, which was

called a bear on account of its great size; this contained several

divisions which contained archers and could be raised to fire down on

the besieged, against which some stone throwers (petraria)

were manfully deployed, which for a long time held back its power of

damage... Barges were also transported from Cheshire by costly

labours, in order to attack the castle by water, but without

success.... they did not attempt to bring down the walls by miners and

mining... From morning until evening the gate was left open....

but a general attack was never made by the king's army, instead the

besieged almost every day went sallying out.... One active

soldier of noble blood was severely wounded in such conflict and

captured by the besieged and taken into the castle where he succumbed

to his fate. He was honourable placed in a coffin with candles

around it and carried outside to his friends, coming from the king's

army, who carried him peacefully off to be buried according to his

wish... Always outside 11 catapults (petrariis) were shooting stones into the castle day and night.

From this it is quite clear that the royalist army was never strong

enough to actively launch a scaling assault upon the fortress and the

siege of Kenilworth castle was more of a battle with the castle being

used as a rebel camp which the attackers attempted to nullify with

artillery. About 2 July 1266, Legate Ottobon, attired in his

cardinal's red cape, stood outside the fortress and excommunicated the

garrison and all those who aided them to the detriment of the peace of

the kingdom. The rhyming chronicler, Robert of Gloucester,

recorded the occasion and the garrison's response.

Cope and other clothes they late made of white

And Master Philip Porpeis, that was a cunning man,

A clerk and hardy of his deeds and their surgeon,

They made a white legate in his cope of white

Against the other read, as him in despite

And he stood as a legate upon the castle wall

And excommunicated king and legate and their men all.

In the meantime both sides fired a prodigious amount of crossbow bolts

that resulted in much bloodshed on both sides. In regard to this,

on 9 August 1266, the sheriff of London was ordered to send 20,000

quarrels of one foot and 10,000 quarrels of two feet to the king

‘as he is in extreme need thereof for the present siege of the

castle'. Presumably the besieged were having to repair and reuse

the bolts fired into the castle.

Then at the end of October, the Dictum of Kenilworth was announced at

the Kenilworth parliament. This was to apply to all the rebels

except for Earl Robert Ferrers (d.1280) and the heirs of Earl Simon

Montfort - the fate of the latter being in the hands of King Louis of

France. The Dictum otherwise stated that the king would accept

back all those rebels who were willing to pay for the crimes they had

committed over the last 2 years. This was to be done by them

buying back their lands at various rates from 2 to 7 times the annual

value of their estates, depending upon their crimes during the time of

war. Kenilworth garrison, now chronically short of supplies and

becoming less able to mount an aggressive defence, said they would

abide by this if they were not relieved within 40 days and so sent

messengers under royal safe conduct to Simon Montfort (d.1271)

informing him of their decision. Within the castle things were

getting worse with their food almost gone. Consequently, they

feared that many of them would fall sick and die if the siege continued

much longer. Further:

the rest of the castle

buildings had been so broken by the artillery and owing to the scarcity

of wood for burning, they could no longer withstand the unseasonable

cold of the winter season.

Accordingly, they sent Richard Amundeville, 2 other knights and 5

others, to Simon Montfort (d.1271) to tell him of their plight and

their need to be relieved within 40 days. Some days after this on

9 November 1266, a safe conduct was given for Robert Overton to leave

Kenilworth castle to come to the king and return. Quite likely

this was to do with the potential surrender of the castle. When

the 40 days had passed the garrison surrendered and left the castle

with all their belongings as agreed, even though they had supposedly

heard nothing back from Simon Montfort (d.1271). Consequently on

14 December 1266, a safe conduct was issued to last until January for

Henry Hastings (d.1268), Richard Amundeville [who had supposedly gone

to Simon Montfort], John Clinton [probably John Clinton of Coleshill

and Maxstoke (d.1316), the third great grandnephew of Geoffrey Clinton

(d.1131/33)], John Easton and others who were ‘part of the

munition and detention of Kenilworth castle, to depart to their own

parts and wither they will on condition of their good behaviour'.

With the siege finally over the king left Kenilworth for Warwick on 16

December 1266. The next day, 17 December 1266, King Henry granted

to Ralph Blundel and Isabel his wife, ‘in compensation for their

losses caused by the occasion of the siege of Kenilworth, of all the

king's houses or buildings together with the lodges (logiis)

in the close from where the king made the said siege'. The king

had similarly, on 18 September 1266, granted the prior of Kenilworth

exemption from purveyances due to the grave losses he had suffered

during the siege of Kenilworth and the courtesies he has shown the king

during that time.

The great siege of 172 days left some odd legacies. Kenilworth

castle, although the lesser buildings were much deroofed seems to have

come through the storm largely intact, although excavations in the

1960s turned up some of the stone balls thrown by the siege

engines. These weighed up to 300 lbs or 20 stone. The siege

was also so long and the number of men needed to enforce it so numerous

that King Henry had to even pawn the jewels from the shrine of King

Edward the Confessor in Westminster abbey to keep his army

together. Other bills included £75 13s 9d allowed to the

sheriff of Warwick in 1269 for the 255 quarters of wheat, 52 oxen and

173 sheep sent to the king's army to help sustain them during the

siege. Finally, the collapse of Montfortian resistence and exile

of the Montforts left the king free to grant all the earl's old lands

and titles to his younger son, Edmund (d.1296). In 1268 he was

made earl of Lancaster and so Kenilworth became one of the great

castles of the future Lancastrian dynasty that would rule England from

1399 until 1461.

Despite the celebrated nature of the siege of Kenilworth, the fall of

the castle in 1266 really ended the story of the medieval

fortress. In 1279 it was the scene of the first Round Table

tournament in England. That summer:

Lord Roger Mortimer the

second held a round table at Kenilworth, of a kind which no one else

had ever held before; at which time King Edward made the sons of the

said Roger, that is Roger, William and Geoffrey, knights at London;

from which city the said Roger, emblazoned in his armour, moved with

100 knights and as many ladies to Kenilworth and there for three days

he held a tournament of a kind never before seen; on the fourth day he

led his lion to Warwick, and returned unharmed with his escort; there

he held a banquet for everyone with his own equipment, which is

difficult to describe in detail.

Already Kenilworth was becoming a pleasure palace rather than a

fortress, although it was still to see military use. Earl Edmund

died fighting in Gascony in 1296 and in 1303 his son, Earl Thomas

(d.1322), enclosed a vast hunting park south and west of the

mere. He also founded a chapel chantry or collegiate church in

1313. Some costs involved in the garrisoning of the fortress and

the construction of the chapel have survived in the receipt roll of

Earl Thomas of that year under Constable Ralph Schepeie of Kenilworth

castle. Amongst his accounts were listed £18 4s for the

wages of 6 chief tenants staying within the fortress as the castle

garrison for a year, each taking 2d per day. A salary of £6

was paid to the 2 castle chaplains and 4s 4d was spent on the lighting

the castle chapel for the year where services were said for Thomas'

parents. Other expenditure included 3s 8d for parchment to make

this expenditure roll and the court rolls, 3s ½d for canvas for

money purses etc. Other expenditure included a Welshman living in

the castle for 7 weeks, the wages of 2 fishermen fishing in the great

pond at 3s 8d for 12 days, the expenses of Hubert the swan keeper, who

had bought 2 barges for the ponds, 3 locks and nails for the earl's

chests, 29s 2d for the costs of imprisoning Nicholas Verdun [the

brother of Theobald Verdun (d.1316) of Ludlow, Longtown and Stokesay

castle] in the castle for 56 days and 5s 8¾d for a groom and

stallion coming to Kenilworth to mate the earl's mares. The total

cost of all this came to £42 12s 4¾d. Work on the

chapel was also well underway costing £141 2s 9d for the

quarrying, breaking, carrying, measuring and cutting the stone as well

as 100 oaks for timbers and refurbishing the masons' tools.

Also in 1313, William the chaplain, who was keeper of the castle stock

entered his expenses of £156 15s 1½d. From this he

had spent various sums on clearing and levelling a plot next to the

castle mill ‘hard up to the castle wall' and within the castle

itself to build a granary as well as clearing away the old, ruinous

granary and building the new one which contained 36 boards, 4,000

roofing shingles, 10,700 nails and various amounts of plaster, stone

and gutters. He also spent £5 4s 9½d in building a

new mill outside the castle and £6 6s ½d for another

within the fortress. Next he accounted for 32s 10d for paying

masons and carpenters to repair the earl's garderobe with 1,500

shingles, 1,000 laths and 3,100 nails and then 14s 7d for carpenters to

remove the doors and partitions on Robert Holland's chamber and then

repairing it with 1,000 tin nails. Of more import was the expense

of 24s 6½d for having a mason stop up and point the window panes

of the great tower and repairing the step at the keep's entrance and

the repair of its chimney, for which 500 tiles and 2 sesters of chalk

were bought. Further costs of 48s were incurred for carpenters

roofing and repairing the hall, pantry, buttery, kitchen, high chamber,

earl's chamber, Ayon's chamber, the constable's chamber, the gate

keeper's chamber and castle chapel together with 7,000 nails.

Then 12s had been spent on the wages of a plumber, a cartload of lead

and 12lbs of tin used to repair the chamber and other buildings and

gutters throughout the year. Finally, 24s 11d had been spent on

roofing and repairing the mill, grange and engine house.

In 1322 Earl Thomas rebelled against his cousin, King Edward II

(1307-29). This led the king to march on Kenilworth castle from

Gloucester on 18 February. Around the same time he ordered the

sheriff of Warwick to blockade the castle ‘which is held against

the king', using the entire power of the county if needs be on 28

February. On 6 March 1322, Peter Montfort of Beaudesert was

ordered to help the sheriff in this task and on 12 March John Somery

[Dudley] and Ralph Basset of Drayton were ordered to seize the castle

for the king's use. The castle probably fell 4 days later on 16

March when the household knight, Ralph Charroun, was given custody of

the castle. The king was certainly in possession of the fortress

by 10 April when he was sending his discomforted prisoners there as

well as arranging the munitioning of this fortress and many others

throughout the realm. Quite obviously the siege had been nothing

like that endured by Leeds castle in the same war.

By 2 August 1322 Constable Ralph Charroun of Kenilworth castle was

ordered to deliver to the mason, Richard Thweites, the goods he had

sequestrated in the castle which belonged to Richard who had made a

chapel in the castle for the earl. Around the same time, Mary

Shepeye, the possible wife of Ralph Schepeie, asked the king for the

return of her property which had been taken when ‘the sheriff of

Warwickshire came and seized the said castle [Kenilworth]... and took

Hugh Quilly and all the goods found in the said castle among which the

said Mary had there 2 hats, 3 hangings, 4 quilts, 4 linen cloths and 8

[....]'. Mary therefore petitioned for their return. Hugh

Quilly certainly died around this time, for simultaneously with Mary's

request, Hugh's widow, Joan asked for some of her husband's forfeited

land, on which she had a claim, to be returned to her as dower.

Most likely he was one of those executed by the vengeful Edward II

that March. Quilly's lord, Earl Thomas Lancaster, had been

executed in Pontefract castle on 22 March 1322. With this

Kenilworth castle reverted to the Crown and King Edward then spent

Christmas 1323 at his newly reclaimed fortress.

Meanwhile, Earl Thomas of Lancaster's brother, Henry (d.1345), had to

be content with the title of earl of Leicester which Edward granted to

him as heir to his brother in 1324. By 28 February 1326,

Leicester had been promoted to earl of Lancaster, but he did not

receive Kenilworth castle. Edward II

returned to Kenilworth again in February 1326 and then stayed from 18

March for the entire month of April when he ordered his chamber valets

to help the local workmen dig a ditch and enclose it with a palisade in

the castle park. Before his visit on 12 February 1326, he ordered

his constable of Kenilworth castle, Eudo Stoke, to select at his own

discretion men to garrison the fortress. The castle was still

being used as a royal prison on 20 May 1326.

With the invasion of England in late 1326, Kenilworth castle passed

back to Earl Thomas' brother, Earl Henry of Lancaster (d.1345), on 21

February 1327. Ironically, Earl Henry captured King Edward II

near Llantrisant on 11 November 1327 and brought him to Kenilworth

castle via Monmouth before 5 December. Even more ironic was the

fact that Edward's chancery kept functioning after his capture and

stated that all the instructions that Queen Isabella and her son,

Edward III, issued from Woodstock actually came from Kenilworth castle

where in reality the king was imprisoned and powerless.

A parliament was called in London and on 7 January 1327, 2 bishops were sent from the assembly to ask Edward II

to appear before them as king. This Edward, after the bishops

reached him at Kenilworth, is said to have haughtily refused,

‘cursing them contemptuously, declaring that he would not come

among his enemies'. On the bishops' arrival back at London with

the answer that the king would resist the counsel of his subjects it

was proposed to depose the king and set up his son in his place, his

audience allegedly responding to Bishop Orleton's oratory on ‘A

foolish king shall ruin his people' with the chant ‘We will no

longer have this man to reign over us'. The archbishop of

Canterbury then read a memorandum which charged Edward II

with weakness, incompetence, taking evil counsel, losing his rights and

possessions in Scotland, Ireland and France and finally for his having

abandoned his realm. The parliament then consented to the

deposition of Edward II and the coronation of his son as Edward III.

Consequently on 15 January, a deputation was dispatched to the unhappy

monarch in his prison within Kenilworth castle. Surprisingly it

took the earls of Leicester and Surrey with the bishops of Winchester

and Hereford, together with Hugh Courtney of Okehampton (d.1340) and

William Roos of Helmsley (d.1343) several days to reach Kenilworth on

20 or 21 January. Here a fraught meeting with Edward resulted in

it being reported that the king accepted their proposal that he should

be replaced by his son, Edward III,

the fact being announced in London on 24 January 1328. The ex

king then remained at Kenilworth under the supervision of his cousin,

the earl of Lancaster (d.1345).

On 3 April 1327, the ex king was moved to the rather odd and remote

location of Berkeley castle. This removal of Edward from

Kenilworth castle was done by force, according to a complaint made by

Lancaster in 1328 and after an unsuccessful attempt had been made to

free him during March. Early in 1328, Kenilworth became the earl

of Lancaster's base for a potential rebellion against the new King Edward III (1327-77), but relations were rapidly patched up in the Spring. The rapprochement was sufficient for Edward III

to stay at Kenilworth while Lancaster was in France and Queen Isabella

and Roger Mortimer (d.1330) were staying at the castle - from late 29

October 1329 to 2 January 1330. The only other time in his reign

that the king stayed there was 1-2 May 1348, which suggests that the

place did not hold happy memories for him.

Earl Henry of Lancaster's son, another Henry (d.1361), succeeded his

father in 1345. In 1346 he made a contract to reroof Kenilworth's

great hall at a cost of 250m (£166 13s 4d). The dimensions

of the hall were given as 89' by 45'. This is the same as the

current hall called John of Gaunt's hall. For his services in the

French wars, Henry was made first duke of Lancaster in 1351. On

his death in 1361, Kenilworth and his estates passed with his only

daughter into the hands of King Edward III's

son, John of Gaunt (d.1399). Gaunt massively refurbished the old

castle after 1371, continuing the process of converting it into the

great Tudor palace it became. Some of the masons working on this

project were also used by Edward III to similarly convert Windsor

castle. Later on 8 July 1391, King Richard II

(1377-99) sent a writ of aid to Duke John's constable of Kenilworth

castle, John Deyncourt (d.1406), and the mason, Robert Skillington, to

set to work 20 stone diggers, carpenters and labourers as well as to

provide materials at the duke's expense for the next 2 years.

There can be little doubt that this was done to aid the duke in his

building work at the castle.

When Gaunt's son seized the throne as King Henry IV

in 1399, Kenilworth became a royal castle once more. King Henry

VI (1422-71) was a frequent resident at his castle and fled here

in 1450 when he abused and then abandoned London to the rebel Jack

Cade. In August 1456, the royal court, taking 40 cartloads of

guns and other ordnance from the Tower of London, again moved to

Kenilworth castle. This was possibly as a consequence of the

Yorkist Constable Devereux of Wigmore castle suddenly descended on

Hereford and then marched on Carmarthen and Aberystwyth, storming both

places in the incipient civil war brewing between York and

Lancaster. Safe within Kenilworth the queen summoned an army from

the Lancastrian heartlands, although it was not used at this

time. Possibly this refortification involved the outer defences

being modified against artillery attack and a gun tower and bulwark

being constructed. Regardless of this, the castle capitulated

after the Lancastrian defeat at the battle of Northampton on 10 July

1460 and was munitioned for Edward IV (1461-83). Ten years later

in 1471, the castle was again Lancastrian when it withstood an 8 day

siege by Edward IV before capitulating.

Richard III (1483-84) also maintained the castle, having the tower next

to the gun tower (le gun towre), the great hall and the king's chamber

repaired over a 15 day period. This seems to have involved their

reroofing in lead as well as some reflooring. Other work included

repairs to the keep (King's Tower) and the tower next to the Watergate

which had timber used in its repair and cost 22s in wages. The

work to the King's Lodging seems to have involved 8 bays and took 4,500

tiles to complete. The work lasted at least 10 days and involved lead and

soldering. Finally various locks, hinges, staples, bars of iron

gutters and ridge tiles were purchased to finish the

refurbishment. The total cost of this work was £23 14s

6d. In 1484 a further £20 was paid to John Beaufitz for

various repairs made to the castle.

Henry VII (1485–1509), like his earlier namesake, was often

residing at Kenilworth and was found there in June 1487 when the

so-called Lambert Simnel invaded his kingdom. Henry also built a

tennis court in happier times. His son, Henry VIII

(1509–47) dismantled Henry V's Pleasance from the other side of

the lake and re-erected parts of it within the castle. He also

built a timber structure closing the inner ward to the east and at some

point in his reign spent £7 3s 11½d on refurbishments to

the straw and tiled roofs. Eventually in 1553 the castle was

granted to Duke John Dudley of Northumberland (d.1553). It was

later in 1563 given to his son, Earl Robert Dudley of Leicester

(d.1588), the favourite of Elizabeth I (1558-1603). Dudley made

significant structural improvements to the castle and entertained his

queen at this palace 3 or 4 times between 1563 and 1575. The

improvements included ‘the filling up of a great proportion of

the wide and deep double ditch wherein the water of the pool came' in

1563 and the building of Leicester's Gatehouse in 1571/2. This

gave access via a 600' long bridge he had built to the park north of

the mere. Around the same time he built a 4 storey tower

structure, Leicester's Building, especially for the queen's visit in

1572. He then had it improved for her next visit in 1575.

Leicester's works are rumoured at the time to have cost some

£60,000, while his entertainment of the queen was supposedly put

on at some £1,000 per day. James I (1603-24) on taking the

throne immediately seized the castle back into royal hands, when it was

found to consist of ‘such stately sellars all carried upon

pillars and architecture of free stone carved and wrought as the like

are not within this kingdom'.

In the Civil War King Charles withdrew his garrison after the battle of

Edgehill in the first month of the war (1642-46). The fortress

was then occupied by parliament although in 1643 its commander,

Hastings Ingram, was arrested for being a covert royalist. The

castle remained a parliamentarian stronghold until it was ordered

demolished in 1649. This partial demolishing resulted in the

destruction of both the north wall of the keep and the outer north

curtain wall to make the place indefensible. However, the living

accommodation was left intact. It was probably at this time that

the dam was breached and the mere drained. A Colonel Joseph

Hawkesworth then purchased the castle and estate and divided it up

amongst his men. Around this time a letter was written that

stated that Colonel Hawkesworth and his officers were the new

tyrannical lords of the manor and that they:

pull down and demolish the castle, cut down the

king's woods, destroy his parks and chase and divide the lands into

farms amongst themselves.... Hawkesworth seats himself in the gatehouse

of the castle and drains the famous pool consisting of several hundred

acres of ground.

Hawkesworth was eventually evicted from Leicester's Gatehouse by

Charles II in 1660. During this period, in 1656, William Dugdale

(d.1686) reported that the great tower and the castle battlements had

been destroyed.

Towards the end of the castle's active life in the early seventeenth

century, the castle masonry was valued and reckoned to weigh some

703,574 tons which had a scrap value of £9,196 15s. This

estimate was based upon the walls being 4' thick throughout, although

it was recognised that many were much thicker than this. Other

parts of the castle were valued too. The lead of the water

conduit which was ¾ of a mile long was worth £1,494 alone,

while the iron bars of the windows should fetch £163 10d and the

window glass £107 14s 3d, while Leicester's clock bell mounted in

the keep southeast tower was reckoned as being worth £30

alone. Such values suggest why castles were dismantled and also

say a lot about the profitability of the dissolution of the monasteries

a century earlier.

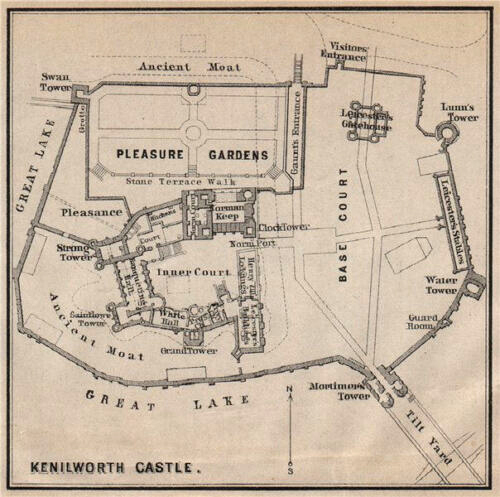

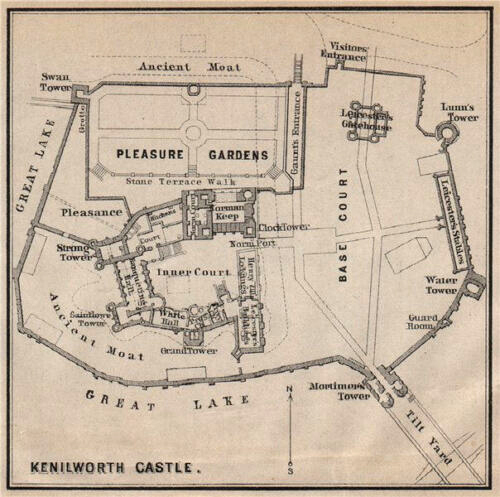

Description

Kenilworth castle is a large military site and is even larger if the

mere or great pool created for the castle's water defences is

included. The style and depth of the water defences make it a

somewhat weaker version of Leeds castle in Kent. Kenilworth

castle seems to have originated on a slight bluff of land overlooking a

depression to its west where the Inchford Brook flowed into the Finham

Brook. It would seem that Geoffrey Clinton (d.1131/33) dammed

this combined brook where the current dam cum tilting yard stands