Richmond

The site of Richmond castle seems to have had a long history, but

this is more civil than military. The county of

‘Richmondshire', of which the castle was the caput, may have

begun with the Norman Conquest, but the name first seems to occur with

the war of 1173-74 when itinerant justices were sent to

Richmondshire. Around the turn of that century Gervase of

Canterbury placed this shire between Yorkshire and Durham the

penultimate entry in his list of the 34 counties of England. To

him Richmondshire included the abbeys of Holme Cultram, Richmond,

Coverham and Egglestone as well as 10 priories which covered the area

from Carlisle to Lancaster and Egremont

to Richmond. However the basis of the ‘shire' was the

honour of Richmond or sometimes the honour of Brittany as it was

sometimes known due to its Breton lords.

From the first, the honour, which later became an earldom and briefly a

shire, was bound up with Breton lords who came over to England with the

Norman Conquest. This means that to a certain degree, the

unravelling of the history of the castle involves delving into Breton

politics. This has been undertaken in a parallel essay.

Another interesting source for the castle history is the Richmond

Register written possibly early in the fifteenth century and describing

the honour in some detail.

It is unknown when Richmond castle was founded, but it is generally

thought to have been established by the first ‘Norman' Count Alan

(d.1094), who was in fact a Breton. According to Gaimar, writing

early in the reign of King Stephen (1135-54), the story began at Hastings where:

Count Alan of Brittany

Struck well with his company.

He struck like a baron.

Right well the Bretons did.

With the king he came to this land

To help him in his war.

He was his noble cousin, of his lineage,

A nobleman of high descent.

Much he served and loved the king,

And he right well rewarded him.

Richmond he gave him in the North,

a good castle fair and strong.

In many places in England

The king gave him land.

Long he held it and then came to his end.

At St Edmund's he was buried.

Although written only 70-80 years after the event, it is noticeable that the Conqueror

gave the earl the castle, apparently as an already functional

fortress. Was this known for fact at the time, or was it

guesswork? There is probably no answer to this, although a survey

of Count Alan's many holdings - 589 manors in chief and lord of 312

other manors in fee - in the counties of Cambridge, Dorset, Essex,

Hampshire, Hertfordshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Northamptonshire,

Nottinghamshire, Suffolk and Yorkshire, might suggest pattens.

These lands were worth £1,067 in 1086. These lands are

stated in the fifteenth century Richmond Register to have belonged to

Earl Edwin of Mercia (d.1071) and were granted to Alan at the siege of York. However, no siege of York is known to have been made by the Conqueror

and in any case Earl Edwin was in honourable captivity at the time so

his lands probably should not have been handed out at random.

Further, the Domesday evidence does not bear the claim out with Edwin's

lands being spread amongst several lords. The Domesday survey

states that Count Alan had within the jurisdiction of his castle 199

manors of which 108 were waste and 133 had been sub infeudated to his

men. In total his lands contained 1,153 geldable carucates of

land and was valued at £80. There were also beyond the

jurisdiction of the castle, 43 vills of which 4 were waste. Of

this 161 carucates and 5 bovates were geldable while there was land for

170½ ploughs. Of these vills his men held 10 and the total

was valued at £110 11s 8d. The existence of a castlery

shows that Richmond castle was in existence by 1086 and lands had been

set up to support this castle which was then a, if not the, major post

on the Anglo-Scottish frontier. The find of a William I

(1066-87) silver penny during excavations in 2021 shows that such

currency circulated in the castle, although the date at which it was

lost is impossible to judge. With this said, it should be borne

in mind that theoretically all coins of a previous ruler were withdrawn

and reminted by the new king. This would suggest that the coin

was lost in the eleventh century.

Richmond, a French name, was not recorded until after 1086. Then

the land consisted of 2 vills. The first bore the name Hindrelas

and consisted of 5 geldable hides and 3 carucates of land, with 1

plough team belonging to the lord and 3 to 6 villains and 2

bordars. There was also a church and priest as well as a wood, 1

league by a half a league in size, the whole manor being 1½

leagues long and half a league wide. The manor was held of Count

Alan by Enisant Musard, but in 1066 had been held by Thor, who had held

some 58 manors before the Conquest, but retained only 4 in 1086.

Between these times Hindrelas had increased in value from 10s to 16s. The other manor was called Hindrelaghe

and had a single geldable hide and a carucate of land together with a

fishery and although it was also held by Thor in 1066 it was now held

solely by Count Alan as waste. Its value had dropped from 10s in

1066 to 1s 4d. The latter was obviously the site of the castle

alongside the river with its fishery, while the former the town at Hindrelas

contained the old centre with its church. Richmond church lies

some 1,000' northeast of the castle keep which again emphasises this

distinction made before 1066. The implication of the 2 surveys

which occur some 50 manors apart in the survey, that the whole was held

by Thor pre 1066 and that Count Alan had divided the 2 when he had set

up his castlery.

These descriptions of the 2 lands offer some interesting figures.

A hide was generally reckoned at some 120 acres although more likely it

was actually a description for the economic potential of the land and

therefore could vary in physical size dramatically. It is usually

accepted that a carucate, or ploughland, was roughly the same size, but

formed under the Danelaw. Broadly this suggests that Hindrelas was 7 times larger (economically rather than physically) than Hindrelaghe.

Enisan Musard, who held Hindrelas of Count Alan in 1086, held a further

26 manors of him in Yorkshire and was constable of Richmond

castle. His alleged daughter, Garsiena Musard, apparently married

Roald the son of Harsculf St James (d.bef.1130). Roald then seems

to have taken the surname Constable as well as the constableship of the

castle, possibly after the death of Constable Scolland in 1146.

Most of what can be realistically said of the first Count Alan is that

he was a popular witness for the king's charters. Of the 41

examples listed in the Regesta Regum Anlgo-Normannorum, at least 12 are

spurious and a few undated ones under William Rufus

(1087-1100) may relate to his brother, Alan Niger (d.1098).

Obviously forgers were well aware of Count Alan's power and acted

accordingly. Indeed, there is even a spurious charter of Alan

being granted ‘all the vills and lands which were once held by

Earl Edwin in Yorkshire'. Clearly Domesday shows that this was

not the case and Edwin's lands were also held by other lords.

Further, the style of this charter is obviously anachronistic and so it

has no value as an original historical document. The first sure

evidence of the count in England occurs on 4 February 1070, when he

appeared with his fellow Bretons, Baderon Monmouth (d.) and his brother

Wethenoc (d.), before King William I

at Salisbury concerning a grant in Monmouth to St Florent, Saumur,

Anjou. As a witness ‘Count Alan' is often to the fore in

the lists, but only twice, on 31 January 1080 and possibly in 1086,

does he appear as plain Alan Rufus and twice in the early 1080s as

Count Alan Rufus. In a spurious charter of 31 May 1081 he is

referred to as Earl Alan to which someone has later added ‘of the

East Angles' (Orientalium Anglorum). The only apparently true grant that exists of lands being granted to Count Alan by William I

is St Olave in Marygate, York, and the adjacent manor of Clifton as

some point after 1070 when Thomas became archbishop of York and 1086

when it appears in Domesday. Thirstino

is obviously a wrongly expanded contraction for Thomas (1070-1100), if

the record is genuine. The only time that Alan is mentioned as

count of Brittany is in a Durham forgery. Mostly Alan seems to

have been described as Count Alan and in the only extant copy of one of

his charters he is described as Count Alan Rufus. The titles of

his descendants will also be noted in this paper with Alan Niger

(d.1146) being the first man noted as actually earl (comes) of Richmond. Similarly before Duke Conan in 1156, no count was more than a count of part of Brittany.

That Alan was a count from Brittany means that the history of Richmond

is bound to some extent with that distant duchy. It is therefore

necessary to delve quite deeply into the history of that area of France

to understand what a count of Brittany and earl of Richmond was likely

to be doing at his northern English stronghold. To briefly

summarise the complex history of the duchy and set the later earls of

Richmond in their context, Duke Geoffrey of Brittany (d.1008) had at

least 2 sons, Duke Alan III of Brittany (d.1040) and a younger son,

Count Eudes of Penthiévre (d.1079). Count Eudes had

multiple sons, some 3 of whom may have been illegitimate. One of

these sons, Ribald (d.1121+) founded the barony of Middleham. The

eldest of Eudes' legitimate sons was Count Geoffrey Boterel of Brittany

who was killed at the battle of Dol on 24 August 1093. Eudes'

next eldest legitimate son was Alan Rufus - Alan the Red

(d.1093). This nickname was given him to differentiate him from

Eudes' other son of the same name Alan Niger - Alan the Black.

Presumably as they both had the name Alan and only one son of Eudes

named Alan witnessed any of this charters, the latter, Alan the Black,

was illegitimate or at least from a second marriage.

Traditionally Alan Rufus commanded the Norman right wing at the battle

of Hastings in 1066. However, an account of doings of the earls

of Richmond written no earlier than 1214 recorded that he came into

England with Duke William, who after becoming king and with the help of

his wife, gave:

the honour and earldom of Earl Edwin in Yorkshire

which is locally called Richmondshire... Initially he began to

build a castle and garrison near his main manor of Gilling, for the

protection of his people against the invasion of the English, who were

then, like the Danes, disinherited everywhere; and he named the said

castle Richemont, in his French idiom, which sounds in Latin like rich

mountain; this was situated in a more prosperous and strong place

within his territory; but he died without an heir of his body and was

buried at St Edmunds.

The grant of Richmondshire is alleged by the fifteenth century Register

of Richmond, without any contemporary evidence, to have been made

during one of the times the king was besieging York in 1068 or

1069. Regardless of the fact that there is no recorded siege of

York by the king, Yorkshire was only really secured by the invaders

when King William carried out his 'harrying of the North' in the winter

of 1069/70. This would have made Richmond a front line castle

with the areas of Cumberland and Westmorland beyond the northwestern

horizon left in hands who did not recognise King William I

(1066-87). The castles which supported this ‘frontier'

during the Conqueror's reign are discussed under Kirkby Lonsdale.

Meanwhile in 1086, Domesday Book showed that the bulk of Alan's other

estates were in the east of England and were all north of London, with

clusters of vills in Cambridgeshire, Suffolk, Norfolk, Lincolnshire and

then around York. Finally, there was a dense mass of vills in

Richmondshire, the then border with Scotland. His most northerly

vill was Lonton about 8 miles north of Bowes. It was only with

the foundation of Carlisle castle in 1092 that Richmond ceased to be a

front line castle. Despite this, Richmond may have appeared

secure by 1083 when Alan was found defending Sainte-Suzanne castle in

Normandy, where he remained until about 1085.

It was probably during this period, 1070-83, that castle guard was

initiated at Richmond. Surprisingly there are several early lists

of the ward owed at Richmond in the twelfth and thirteenth

centuries. This is most unusual and marks Richmond out as a

special castle. It also shows that the fortress began its Breton

life as very much a frontier castle. As such the guard was

probably established when the castle was first constructed or acquired

by Count Alan Rufus (d.1094) around 1070. There is a list of

187¼ fees which owed ward at the castle. This appears to

have been compiled in the late twelfth century, but is based upon the

setup at the start

of that century. This showed that guard at the fortress was

divided into 2 month periods with different knights owing service at

different times. This meant that some 30 knights would have been

serving sequentially each year at the fortress. Quite clearly

such a setup is unique in England and suggests that Richmond was

intended to be the main military centre of the northern frontier.

That this setup was established before 1098 is indicated by the facts

that the 2 sublordships that Count Alan's successor, Count Stephen

(d.1136), created were exempt from guard at Richmond castle.

These lordships were Masham held by Nigel Aubigny (d.1129) and 4 fees

in Swaledale given as dower by Stephen to his daughter, Matilda, when

she married Walter Gant (d.1139) before 1120.

In Domesday book Count Alan was recorded as the fifth richest baron in

the country. He had built St Mary's abbey at York before 1086,

but King William Rufus (1087-1100) refounded it around Lent 1088,

apparently in Count Alan's presence according to Abbot Stephen's own

account. This Stephen was abbot from about 1080 until his death

on 9 August 1112. Many Northern magnates made grants to this

house and these have to be used when looking at the early history of

such castles as Appleby, Brough and Kendal. In the spring

rebellion of 1088, Count Alan was one of the few Norman magnates who

stood with William II (1087-1100). In the September of 1088 he

had been tasked with Roger Poitou (d.1123) and Count Eudes of Champagne

(d.1115/18) to bring the recalcitrant Bishop William St Calais of

Durham (bef.1087-1096) to Rufus' court from Northumberland.

Earlier Count Alan had fought for Rufus at the sieges of Rochester and

Pevensey. During his tenure of power, Count Alan is recorded as

having made gifts to St Mary's of York. The lands granted when

King William II ‘founded' the abbey were Lestingham, the church of

St Botolph in Boston (Hoylanda), land in Skirbeck (Skyrbeck,

Lincolnshire), the mill and church of Catterick (Catricii) and the

church of Richmond with the castle chapel as well as the tithes of his

castlery in Yorkshire, besides those that belonged to the church and a

third part of the tithes of his men of those lands which they held

under him in the aforesaid castlery. Catterick, together with

Gilling, remained the 2 major manors of the honour of Richmond during

the barony's existence.

Considering the count's holdings in Brittany it is to be expected that

he was often abroad. Consequently Richmondshire seems to have

been mainly administered by his steward or dapifer. Indeed one of

these, Scolland, has latterly given his name to Scolland's Hall.

However, he was not the first steward of Richmond. This was

probably Wymark, of whom little is known other than his granting of the

chapel of St Martin of Richmond to St Mary's of York as Wymarus

dapifer. The grant included land in Edlingthorp, Thornton, the

Forest (Forcett?) and Scruton (Scottona) with all the tithes of his lordship of Wicra.

Presumably this grant was made in the eleventh century when St Mary's

was a prime site for religious grants. It is also presumed that

on Wymark's death he was followed as dapifer by Scolland, who is first

mentioned as a witness in 1097 and died on 6 January 1146.

Assuming he was around 20 when he first witnessed he would have been

about 65 at the time of his death. This makes it virtually

impossible for him to have been steward of Count Alan Rufus (d.1094)

when the castle was apparently founded in the 1070s. Scolland's

son Brian (d.1171) was certainly born before 1125 which again suggests

that Scolland was a young man in the late 1090s. Brian's son,

Alan Fitz Brian (d.1188), gave his name to their descendants, the

Bedale Fitz Alans. Scolland was apparently succeeded by Roald

(d.1158), the founder of nearby Easby abbey in 1152. Under Roald

the stewardship of Richmond became hereditary and he and his successors

took on the surname Constable, after their office in Richmond

castle. This brief survey of the Stewards of Richmond of course

ignores Enisan Musard (d.1089+), the constable of Richmond, who is said

to have passed this office onto his supposed son in law, Roald

Constable (d.1158).

Despite all the Domesday evidence, little is known about Count Alan

Rufus, although the dating of one of his grants at Rochester, adds

weight to the suggestion that he took part in the siege of that

fortress in 1088. His Rochester charter was witnessed by several

of his men, namely Wymark the dapifer, Odo the camerarius, Harsculf St

James (the father of Roald Constable, d.1158), Oger Fitz Guidomar,

Guidomar a monk of Swavesey, Hamo Dol [possibly a son of Rivallon Dol

(d.bef.1066)] and Anschitil Furneaux (Asquitells Furnellis).

Presumably this little group was fighting for Rufus (1087-1100).

Count Alan probably died on 4 August 1093, even though the thirteenth

century Margam annals place his death in 1089 alongside that of

Archbishop Lanfranc (d.28 May 1089). According to the St Edmund's

Memorials, after founding St Mary's abbey outside the walls of York, he

was buried at that abbey's mother house, Bury St Edmunds, by Abbot

Baldwin near the south door. However, he was later moved at the

prayer of the monks from York. Has tomb was engraved with the

epitaph:

A star falls in the kingdom; Count Alan's flesh withers:

England is disturbed; the flower of the kingdom-protectors is turned to ashes.

Truly the flower of the kings of Brittany, merely to decay is the order of things.

By the command of laws, the blood of kings rises and shines.

The most honourable, second only to the king;

Seeing this and weep; Rest in peace, God! Pray

He came from the noble race of the Britons.

This should be compared with the epitaph to Gundreda Thouars, the wife

of William Warenne (c.1035-88), which was equally long and carved into

an ornate tombstone.

Count Alan was probably still in his forties at the time of his death,

but left no heir of his body. He was succeeded by his possibly

illegitimate and therefore half brother, Alan Niger (d.1098), who also

inherited his brother's mistress, Gunhilda, the daughter of King Harold

II (d.1066). His control of his brother's barony is affirmed by

King Henry II (1154-89) confirming Alan's earlier grant of Gilling

[just north of Richmond] to St Mary's of York as well as his tithes of

Bassingbourn (Basyngburgh, Cambridgeshire), Haslingfield (Heselyngfeld,

Cambridgeshire) and land in Skelton (Skeltona, 5 miles west of

Richmond). Quite possibly he was the Count Alan who witnessed a

charter in favour of Saumur with Ivo Taillebois (d.1094/8), although

the charter itself has been misdated to 12 March 1100, by which time

both men were dead. In any case, Alan Niger did not long survive

his legitimate brother, Alan Rufus, dying, possibly also on 4 August,

in 1098 and being succeeded by another brother, Stephen (d.1136).

It has been suggested that Stephen immediately inherited Richmond in

1094 to the detriment of his elder brother, Alan Rufus (d.1098).

However, judging by the above confirmation of Henry II and the fact

that on 30 October 1107, Count Stephen confirmed the grants of his

brothers (fratres, plural) in England while he was at Lamballe in

Brittany, this is most likely wrong.

Unlike his other brothers and half brothers, Stephen lived a long life,

apparently becoming count of Penthievre in Brittany in 1094 and then

lord of Richmond in 1098. At some point he made a confirmation as

count of Brittany (comes Britannie). He supported King Henry I

(1100-35) at the abortive battle of Alton on 3 September 1101 and he

pledged for him in the subsequent treaty. Also, unlike his

brothers, Stephen had a large family who were of age before 1123, when

Geoffrey (d.1148) was already a count and Alan was apparently running

his father's English estates. Count Stephen of Brittany, as he

was styled in the charter, was certainly active as a lord of Richmond

as he confirmed the gift of the church or churches of Richmond,

Richmond castle chapel, the cell of St Martin and the churches of

Catterick, Bolton upon Swale, Gilling, Forcett and the chapels of South

Cowton and Eryholme, Ravensworth, Croft, Great Smeaton, Patrick

Brompton, Thornton Steward, Hauxwell and land in Scotton, Little Danby,

Langthorne, Finghall and Ruswick as well as the churches of Burneston,

Hornby and Middleton Tyas. He also granted the tithes of his

demesnes and of his men in Richmond castlery, Holland, Boston church

and land in Skirbeck in Lincolnshire; land in Haslingfield and tithes

in Bassingbourn, Little Abington, Great Linton and Wicken in

Cambridgeshire and finally the tithe of Lyng in Norfolk. This

grant was made at York in the period between 1125 and 1135. The

pipe roll of Michaelmas 1130 also lists a variety of lords who owed

money this year as the men of Count Stephen of Brittany, namely:

|

Lord |

Owed |

|

Scolland |

50m (£33 6s 8d) |

|

(Walter de la Mare) |

(5m (£3 6s 8d) cancelled) |

|

Richard Rullos |

15m (£10) |

|

Ralph Fitz Ribald |

15m (£10) |

|

Roger Fitz Wimar (Wihomar) |

5m (£3 6s 8d) |

|

Roger Lascelles |

10m (£6 13s 4d) |

|

Acharis [Fitz Ernebrand] |

5m (£3 6s 8d) |

|

Hasculf Fitz Ridiou |

10m (£6 13s 4d) |

|

Robert Chamberlain |

10m (£6 13s 4d) |

|

Wigan Fitz Landric |

5m (£3 6s 8d) |

|

Robert Furneaux |

10m (£6 13s 4d) |

|

Osbert Fitz Colegrim |

1m (13s 4d) |

|

Alan Fitz Eudo |

3m (£2) |

|

Demesne manors |

20m (£13 6s 8d) |

|

Total |

139m (£92 13s 4d) |

Of the account rendered, which was not totalled but came to 139m

(£92 13s 4d) a full 100m (£66 13s 4d) was paid into the

treasury and the king pardoned Count Stephen the remaining 59m

(£39 6s 8d) - totalling £106 exactly. This pardon,

although 20m (£13 6s 8d) more than that apparently owed, made the

account quit. A few entries later there were a list of pardons

granted by the king. The first entry in this has Count Stephen

pardoned 5m (£3 6s 8d) owed by William Lamara. Several

entries later comes a further pardon granted by the king. Under

this the count of Brittany was pardoned 22m (£14 13s 4d) for his

lesser men, after which Ralph Fitz Ribald of Middleham (d.1168+) was

pardoned 5m (£3 6s 8d) and then various other men various amounts.

Count Stephen founded 2 abbeys, Holy Cross at Guingamp about 1110 and

Begard in 1130. This suggests that his main sphere of operations

was in Brittany, rather than Richmond. Simmilarly he apparently

left most of his progeny in France, but his second or third son

inherited the honour of Richmond in 1136 as Alan Niger (d.1146).

Alan had possibly been administering Stephen's English estates from

before 1123 when he was noted as being in England, unlike Count Stephen

and the rest of his family. According to the family abbey of St

Mary's at York, Count Stephen and his wife, Hawise, had their obits

celebrated on 21 April. However, the Genealogy of the Earls of

Richmond dates his death to 30 March 1164. MCLXVI is quite a

mistake from MCXXXVI, but obviously possible. Whatever the case,

the count seems to have died in the spring of 1136.

Alan Niger was twice recorded as earl of Richmond in royal charters at

Westminster between mid May 1136 and 25 March 1137. He remained

loyal to King Stephen (1135-54) throughout his life. As was

standard policy for the time, his elder brother, Count Geoffrey Boterel

(d.1148), supported the other side and was recorded as the brother of

Earl Alan of Richmond when he fought for the Empress at Winchester in

1141. Meanwhile Earl Stephen was one cause of the arrest of the

bishops at Oxford on 24 June 1139 where his unnamed nephew was

killed. The next year he was made earl of Cornwall, apparently as

heir to his uncle, Brian (d.1084+), who was mentioned in the charter

and had been an earl in England under the Conqueror. During 1139

Earl Alan was fighting in Yorkshire according to one chronicler.

In the same year Earl Henry [of Huntingdon, d.1152]

went with his wife to the king of England. Earl Ranulf of

Chester, rose up in enmity against him on account of Carlisle and

Cumberland which he wished restored to him by right of patrimony and so

he intended to engage him on his return [from the king] by the armed

hand. However, the king, warned by the entreaties of the queen,

protected him from the intended danger, and so restored him to his

father and his country, and thus the indignation [of Ranulf] was

transposed into a plot against the king's safety, for Earl Ranulf took

possession of all the garrisons of Lincoln. Earl Alan, climbing

by stealth at night over the wall, broke into the castle of Helmsley

(Galclint,

probably Gelling nearby) with his men, and took possession

of the castle itself with abundant treasure, driving out William

Aubigny with his men. The same Earl Alan of Richmond, fortified

the castle at Hutton Conyers (Hotun, 2 miles northeast of Ripon on the

River Ure), that is in the land of the bishop of Durham, and his hand

was heavy upon Ripon and the people of that place. For he and

other powerful men took whatever things in the barns and other things

which Archbishop Thurstan had reserved for his successor, as each of

them was a neighbour to the archbishopric's lands.

A single charter of Alan survives to Mont St Michael in Cornwall. This is dated 1140 at Bodmin (Bomne) and began:

By the grace of God, Count Alan of Brittany and

Cornwall and Richmond, to all his faithful men and the sons of the holy

church established in Cornwall.

It concerned his grant of a fair at Marazion (Merdresem) and was

witnessed by amongst others, Roger Vautort of Trematon (Racorus de

Valle Torta). However, Alan was soon displaced in Cornwall by the

Empress Matilda's half brother, Reginald Dunstanville (d.1175),

possibly soon after he had fled the battle of Lincoln at the first

enemy charge. At least one contemporary blamed his flight for the

spread of disorganisation throughout the royalist troops. Before

the battle, Earl Robert of Gloucester (d.1147) is said to have made a

speech in which he laid into his enemies. The first of these was:

Count Alan of Brittany, in arms against us, nay

against God himself; a man so execrable, so polluted with every sort of

wickedness, that his equal in crime cannot be found; who never lost an

opportunity of doing evil and who would think it his deepest disgrace

if anyone else could be put in comparison with him for cruelty.

According to the Durham chronicler, Symeon, as soon as the king led his men into battle;

Earl Alan of Richmond and his troops, before the

fighting had even begun, renounced both the king and the battle.

Alan, however, apparently remained true to his king, unlike many

others. After Stephen had been transferred to his prison at

Bristol, the earl of Richmond sought to capture Earl Ranulf of Chester

(d.1153/4). Unfortunately his ambush went awry and it was Alan,

‘a man of great ferocity and guile' who was captured in the

skirmish. He was then incarcerated in ‘a filthy prison'

while his earldom of Cornwall was overrun. He only gained his

freedom on paying homage to the earl of Chester and placing all his

fortresses, which would have included Richmond, at Ranulf's

service. Symeon saw this somewhat differently and stated:

Earl Alan of Richmond summoned a conference where he

was seized by Earl Ranulf who, after being starved and inflicted by

other tortures was himself forced to surrender the castle of Galdint

(ie. Helmsley) and the treasure found within it.

Both versions obviously related to the same event and as a result of

his capture Alan seems to have lost control of many of his lands and

possibly even Richmond castle, although he seems to have remained its

master as a man of the earl of Chester. It would also appear that

he lost control of Devenis, his Dorset manor, to the earl of Gloucester

at this time. Despite these setbacks, Alan was free by Christmas

1141 when a recently released King Stephen made a grant witnessed by

the following barons, presumably in order of their rank, viz, Earl

William Warenne, Earl Gilbert of Pembroke, Earl Gilbert of Hertford,

Earl William of Aumale, Earl Simon, Earl William of Sussex, Earl Alan

and Earl Robert Ferrers. That said, in the summer of 1140 at

Norwich, the earls had been listed as, Earl Alan, Earl William Warenne,

Earl Simon and Earl William Aubigny, so perhaps the order doesn't imply

that much. Similarly in the period 1141-43, the earls in another

charter were listed as Count Alan of Brittany, Earl William Warenne and

Earl William of Lincoln. Count Alan was obviously of a warlike

nature for soon after Easter 1142 the king thought it necessary to

prohibit a tournament that Alan and Earl William of Aumale were

planning to hold at York.

After Easter, King Stephen, accompanied by his

queen, Matilda, came to York, and paid off the soldiers who had been

hired by Earl William of York and Earl Alan of Richmond, who were to

fight against each other for the nine day holiday; for he hoped to

avenge his former injuries and to restore the kingdom to its ancient

dignity and integrity, however, being anxious about the weakness of the

knights he had recruited, he sent them back home.

Alan was still in England in 1143 when he and his armed men burst into

Ripon church and abused Archbishop William of York and irreverently

dishonoured the body of Saint Wilfrid. An epitaph of sorts was

written for him in the Brittany Chronicle. This read:

Earl Alan died, who had been most active in England

and Brittany, whose intention was to restore the dignity of the kingdom

of Brittany. As a juvenile he was indeed a most cruel and

predatory man, but when he became a man he was a father to his country

and a most watchful lover of the church.

The terms of the chronicle are vague, but they imply that Alan's

attitude matured when he married. Charter evidence shows that

this occurred before 1135, but his actions at Ripon hardly suggest that

he loved the church in 1143. Therefore the comments about his

change of attitude should perhaps be taken with a pinch of salt.

That he left England for Brittany in 1145 seems likely, which suggests

that campaigning might have brought him low in 1146. Certainly

his early death preshadows that of his grandson in 1171. During

the early years of the Anarchy it seems possible that Alan was also

operating a royalist mint at Richmond castle. He also used an

unusual form in some of his charters, mainly Alanus comes Britannie et

Anglie - Count Alan of Brittany and England. Perhaps this form

indicates his priorities in life with Brittany being utmost in his mind.

It must have been shortly before his death, which was also recorded as

having occurred on 15 September rather than 30 March 1146, that Count

Alan made at least 2 grants to Jervaulx abbey. In these he was

recorded as Count Alan of Brittany and England, while the second was

addressed to his seneschal and constable of Richmond as well as all his

barons and liegemen, French, Breton and English. At a later date

Roger Mowbray testified:

that before I went to Jerusalem on my pilgrimage the

first time which was 4 years before Walter Bury had the land in

Mashamshire, I gave it to the abbey which was then called Carita, and

is now called Jervaulx....

In this charter he further stated:

Not long after the donation, Count Alan crossed over

to his own lands in Brittany. When he arrived at Savigny, he

informed the abbot and the congregation that Brother Peter and other

monks who were associated with them, had started an abbey in their

domain not far from his castle of Richmond in England [Jervaulx is some

10 miles south of Richmond]. And the same count at once gave that

abbey, whatever it might have been at that time, to the abbot of

Savigny himself, who received it, but as if reluctantly and

unwillingly, and he held it well and in peace, but for how long it is

not established.

During 1146 at St Albans, King Stephen made a grant to Earl Ranulf of

Chester of all the lands which had belonged to Ernisius Burun except

for that which he had given to Earl Alan in Yorkshire. The

linking of the 2 earls together may be a throwback to the homage Earl

Ranulf forced from Earl Alan in 1141, although it is likely that King

Stephen disallowed this humbling of his loyal baron. Whatever the

case, Earl Alan died young in Brittany, possibly on 30 March 1146 when

he was probably not much over 46. Likely soon after he heard of

Earl Alan's death, Pope Eugene III (1145-53) confirmed the cell of St

Martin with its appurtenances and the church of Catterick on 11 August

1146 to St Mary's of York. Apparently at the same time he

conformed Richmond church, the castle chapel and everything else in the

castlery. The record of this confirmation was later found in the

tower of St Mary's York. If this was done in response to the

count's death then this must have occurred in March rather than

September 1146.

Earl Alan (d.1146) left at least one son who was apparently

underage. Alan's widow went on to marry Eudes la Zouche of

Porhoet (d.1185) in or before 1148. He then assumed rulership

over the duchy in her name, after the death of her father, Duke Conan,

that year. In 1149 Eudes founded the abbey of Notredame de

Lantenac. In this he was acting as duke in right of his

wife. However by the period 1152-56, Eudes witnessed a document

of Ralph Montfort as Duke Eudes of Brittany. This rather suggests

that his power had grown in the intervening years. Meanwhile back

in England according to the fourteenth century genealogy of the family

translated at the end of this page:

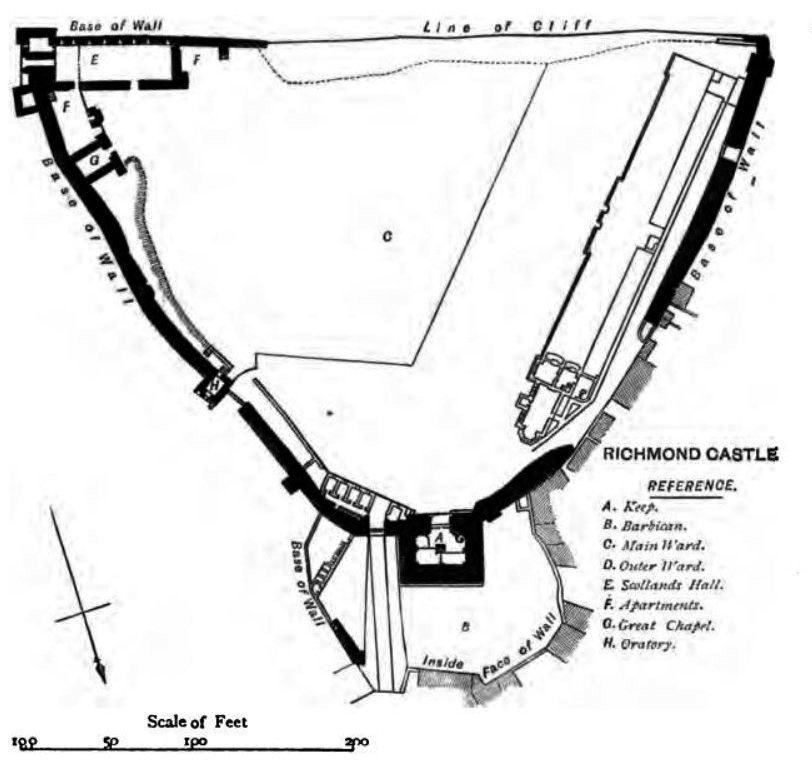

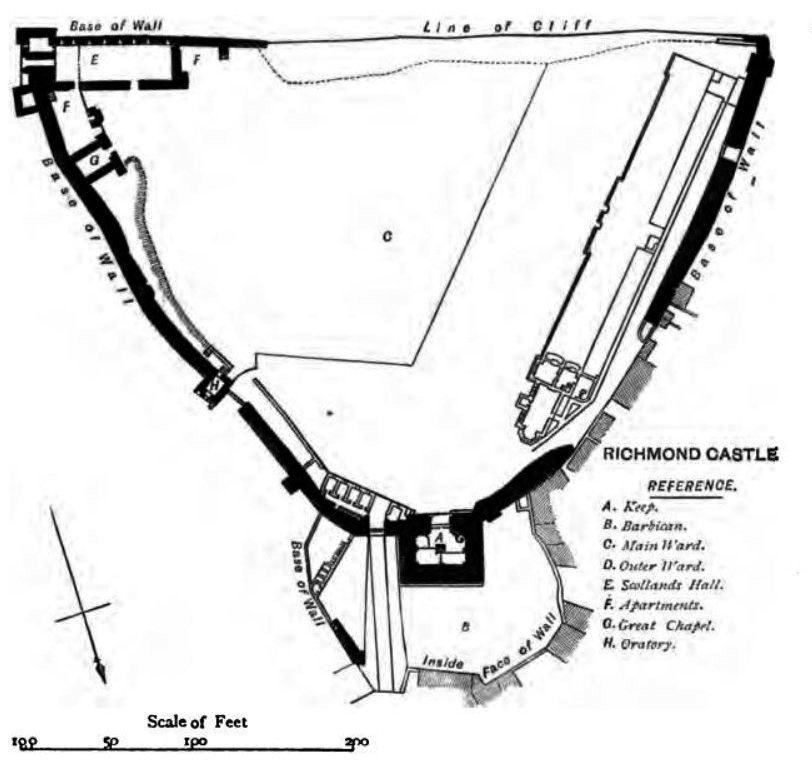

Count Conan Fitz Alan of Brittany and Richmond,

succeeded to the honour of Richmond and married Margaret, the sister of

King William of Scots, by whom he had a daughter and heiress named

Constance who Geoffrey the brother of King Richard married. This

Conan built the great tower within Richmond castle (turrim magnam infra

Castellum Richemundiæ) and died in Brittany being buried at

Begard in 1170.

Unfortunately this precis is rather condensed and gives no idea as to

when Richmond keep was said to have been built other than during

Conan's active lifetime (1146-71). The piece itself may have been originally compiled as early as the reign of Richard I (1189-99) considering that

Geoffrey (d.1186) is described as King Richard's brother, rather than

the brother of the Young King Henry III (d.1183) or King John(1199-1216).

However, the passage is found in a document that cannot predate 1341.

Regardless of the value of this statement, it is necessary to

study what is known of Conan's life history to help in

suggesting when Richmond keep may have been built. Further,

unravelling the history

of Brittany is certainly necessary to have an idea of the type of man

who

ruled at Richmond.

It is uncertain how old Conan was in 1146, but he may have been

underage, apparently initially being known as Conan Fitz Bertha, the

son of Alan Niger. Certainly his mother described herself as

‘Bertha, by the Grace of God Countess of all Brittany' and

associated her son Conan with her in a grant. This indicates that

Conan was underage at the time of Earl Alan's death and that his

mother was the main power in the family, although this surely should

not have happened before 17 September 1148 when her father, Duke Conan,

died. The witness list is also

interesting as Conan appeared as the first witness as Conano consule,

he was followed by Bishop Solomon of Leon and then Count Eudes, who

presumably was not yet Bertha's husband, their marriage occurring in or

just before 1148. The charter was probably made in 1146 as a

codicil was added ‘22 years later' by Bertha and her son Count

Conan. Such a codicil could not have been made after August 1167

as Bertha was dead by then, her husband Eudes having remarried a

daughter of Hervey Leon. This means that the very latest the

original charter should have been made in was 1146, 21 years

previously! Obviously there is a trouble with dates here.

Le Baud, writing over 300 years later, considered that Eudes had denied

Conan his inheritance and that the 2 were mortal enemies from the first

and that after a battle Conan was expelled to England in the late

1140s. If Le Baud was using a now lost source, no trace of it now

seems to remain. The dangers of using sources like Le Baud are

again emphasied when he places the 1146 death of Count Stephen as

taking place from leprosy in 1164. In this he is undoubtedly

partially following, or creating, the error in the Richmond Genealogy. Yet Le Baud

should have known that by 1164 Stephen would have been well over 100

years old.

The sum of this evidence would therefore tend to suggest that Conan was

underage in 1146 and that any early battle against Duke Eudes never

took place, though Conan would appear to have been in England prior to

1156 and certainly made a charter at Richmond as duke of Brittany and

earl of Richmond before the death of Roald Constable in 1158. He

also seems to have been with King Henry II (1154-89) witnessing one of

his charters at Worcester, probably in 1155 as Earl Conan of

Richmond. This charter was made probably between July and

September 1155 in the aftermath of the campaign against Hugh Mortimer

of Wigmore (d.1181). Another charter suggests the king was either

in Worcester or Winchester around 30 September 1155. This

probably makes Conan a royal supporter during the Mortimer rebellion.

By 1156 Conan was certainly old enough to undertake a campaign in

Brittany which would suggest that he was born some time before 1135,

his father having been born before 1100. Certainly when Henry II

came to the throne in 1154, Conan would seem to have been already

accepted as earl of Richmond, no doubt protecting the border with

Scotland which probably lay between the Scottish held site of Brough

castle, only 25 miles to the northwest. Roughly half way between

the 2 lay Conan's own castle of Bowes, guarding one of the main passes

between what was then England and Scotland. There is a singular

statement in the 1156 pipe roll that Earl Conan had received £9

10s that year in Suffolk as the third penny of Ipswich (Camit').

This third penny of the pleas of Ipswich had been granted to Count Alan

Rufus (d.1094) by William I (1066-87) and is mentioned in

Domesday. Ranulf Glanville (d.1190) again rendered account for this sum in

1172, after Count Conan's death in 1171.

The history of Conan's tenure of Richmond castle can be gleaned in

outline from the various chronicles that record the history of Brittany

in this period. However, they appear to be all later compilations

and suffer contradictions in their chronology with several events being

recorded a year or two out and some being placed in a wrong

order. The following is a reasonable interpretation of the

evidence.

From about 1148 Brittany had been ruled through Eudes Porhoet, who had

married Earl Conan's mother, Bertha, before that date. They were

opposed at this time by Bertha's brother, Hoel (d.1156), who held power

at

Nantes and described himself as the son of Count Conan (d.1148) and

duke of

Brittany. In one of his charters he states that the grant he was

making was with the consent of his sister, Countess Bertha.

Eudes, with his wife, Bertha,

seems to have held the north of the duchy at this time based upon

Rennes, while Hoel held the south based upon Nantes. The

political relationship between Conan and his mother is not recorded at

this time, but as they both sealed a grant to St

George's abbey, Rennes, it would suggest that they had at least been

reconciled by the end of Bertha's life. Certainly Conan and

Bertha's husband, Eudes, were political enemies in the late

1150s. The contemporary Robert Torigny made 2 entries about this

war, sandwiched between his account of the storms and floods of July

and

August 1156. This suggests that Conan's attack on Rennes happened

around that time and that Eudes was captured after August.

According to Du Paz writing in 1619, a chronicle of St George of Rennes

stated that Earl Conan crossed to Brittany in September 1156.

Against this Torigny states:

Earl Conan of Richmond came from England to Lesser

Brittany and laid siege to and took Rennes city, putting to flight his

father in law, Viscount Eudes.

Following this:

Ralph Fougeres (d.1194) captured Eudes, the viscount of

Porroet, in battle. Consequently most of the Bretons accepted

Conan as duke, with the exception of Jean Dol (d.1162), who still

manfully held out against Conan and his adherents.

Conan's invasion would appear to have happened soon after King Henry II's

brother, Geoffrey (d.1158), had been installed in Nantes at the will of

King Henry II (1154-89) and the citizens of Nantes. One chronicle

states that Count Eudes somehow escaped Brittany to Paris that same

year and then fought for King Louis at Lyons. However, this is

probably a misdating of events in 1171 which are related below.

This leaves the question as to was Conan acting under the orders of

Henry II (1154-89) during this first Breton campaign or was he acting

independently? In January 1156, the king had left Dover for

Witsand in the Low Countries and then moved on to Rouen by 2

February. During this time he made some half dozen charters which

have survived. None of these are witnessed by Earl Conan, so it

is reasonable to assume that he did not accompany the royal court at

this time, nor did he take part in the sieges of Chinon and Mirebeau

that Spring, nor was he at Chinon in July for the peace made between

King Henry and his brother, Geoffrey (d.1158). The king then

progressed through Anjou and into the Limoges by October. This

suggests that he showed little concern for earl Conan making himself

duke of Brittany - leastways for his attack upon Count Eudes and

Rennes. All that can be said of Henry II and Richmond in

Yorkshire is that the king made a charter there at some point in his

reign which was witnessed by Hugh Murdach, Ranulf Glanville (d.1190),

Michael Belet (d.bef.1205) and William Bending (d.1191). The

lives of the witnesses would suggest that King Henry visited the

fortress after the death of Duke Conan in 1171.

In any event, after the subversion of Nantes and Conan's subsequent

occupation of Rennes, Conan and Geoffrey seem to have divided the

province between themselves just as Eudes and Hoel had earlier divided

it. The only difference was that both conquerors now owed

allegiance to King Henry II (1154-89). Certainly at some point

between 1156 and 1171, Conan made several charters as duke of Brittany

and earl of Richmond. The most interesting of these concerning

the honour of Richmond is his confirmation of lands to Easby abbey -

this included Richmond castle bridge which had been granted by Robert,

Duke Alan's usher (hostiario). Other grants were made at Richmond

itself.

As there is no contemporary title recorded by Count Geoffrey (d.1158)

it is to be presumed that he held Nantes and Lower Brittany of Duke

Conan, although he may also have been holding it directly of his

brother, King Henry II. According to a Breton chronicle,

undoubtedly written in retrospect, at some point in 1156, after

Geoffrey, the younger brother of Henry II (1154-89), was received in

Nantes as duke:

Conan Fitz Bertha, was received by the Bretons as

leader and prince; but King Henry of the English, though it was not his

due, desired to have the city of Nantes with its dependencies.

This leaves the actual status of Nantes uncertain in this period and

opens up the possibility that the third penny of Ipswich was

no longer paid to Conan after this date as he was now duke of Brittany,

possibly without King Henry's permission. It is possible that the king visited Rennes at this time. Certainly during that

winter of 1156/57 he attacked Thouars and appeared in Normandy at Caen,

Mortain, Rouen and Valognes before returning to England through

Barfleur around March 1157. There is no evidence that he met

‘duke' Conan in this time.

During July 1157, King Henry extended his northern frontier of England

from the district around Duke Conan's castle of Bowes up to Carlisle

after his meeting with King Malcolm IV of Scotland at Peak

castle. This meant that Richmond was no longer a front line

castle and this change would have redefined Duke Conan's political

relationships with both kings, Henry and Malcolm.

The next mention of Conan occurred on 22 April 1158, when he was

recorded as Duke Conan of all Brittany and earl of Richmond. This

charter was made to St Melaine abbey, Rennes, while he was staying in

the city. The same year Conan made another charter at

Fougeres. Probably this was when he was visiting his cousin Ralph

Fougeres (d.1194), or his father, Henry (d.1162). Around the same

time the duke made a confirmation charter to Fountains abbey which had

been agreed before the duke and his barons at Richmond castle.

Events at this time came hard and fast. On 26 July 1158, Count

Geoffrey of Nantes suddenly died, aged only 24. This surprise

caused Conan to promptly seize the lower half of Brittany to the

consternation of Henry II who at the time was progressing around the

southwest of England before campaigning in Deheubarth against Prince

Rhys ap Gruffydd (d.1197). On hearing the news Henry rushed south

and crossed the Channel to Normandy on 14 August 1158.

The events of these years in Brittany were recorded in retrospect by

William Newburgh writing around 1196. He stated that after the

rebellion of Geoffrey (d.1158) in Anjou, during the early part of 1156,

Henry II (1154-89) besieged Chinon castle and took it with Loudun and

Mirebeau castles [Spring 1156], then:

He allowed his brother to come humiliated and

supplicant to him, while the fortresses were stripped from him, in

order to prevent his future ambition, he conceded him some level land

which would provide for him. And then he [Geoffrey] would be

filled with sorrow, and then the anger at his brother, now groaning in

envy at fickle fortune; he was suddenly exhilarated by a happy

event. It happened that the citizens of the illustrious city of

Nantes did not have a certain master in whom they were pleased; having

seen the industry and energy [of Henry II], they invited him to choose

a true and certain master for them and having secured the city,

surrendered it with the adjacent province to him [Geoffrey]. But

not long after this happy event he [Geoffrey] was taken away by an

untimely death, and soon the earl of Richmond, who at that time

presided over a great part of Transmarine Brittany, entered the same

city as the true possessor. On hearing this, the king, having

ordered the finances of the county of Richmond to be applied to the

treasury, immediately crossed from England to Normandy, and demanded

the city of Nantes by right of fraternal succession; thus the same

count, startled by the terror of his [the king's] preparations, was

overthrown and broken, so that, scarcely tepidly endeavouring to

struggle, he instantly resigned the city to placate [the king].

As ever, this ‘historical' summary made with hindsight, is not

quite right. On Conan seizing Nantes, presumably in August 1158,

King Henry's first port of call was the Vexin to meet with King Louis

VII (1137-80). Here Louis made Henry seneschal of France and bade

him to go and pacify the troublesome Bretons. Henry then

called for an army to be formed at Avranches at Michaelmas to bring

Conan to heel. On the allotted day, not only had his knight

service formed, but

Count Conan of Rennes, accompanied by his Bretons,

came to Avranches and there he surrendered to the king the city of

Nantes with the whole county of de la Mee (the district around Nantes),

valued it is said at 60,000s Angevin [approximately £750, an

Angevin shilling being a quarter the value of an English one].

It is clear from this that Conan attempted no resistence to Henry,

there being little time between Geoffrey's death on 26 July and Conan's

submission on 29 September for major hostilities to have

occurred. Indeed, Duke Conan made a charter at Rennes on 22

September 1158, just a week before he met King Henry II at

Avranches. It is also clear that Conan remained duke of a semi

independent Brittany after this event, there being no mention of him

granting away the rest of the duchy at this time. Presumably the

earl of Richmond then accompanied the king as he reviewed the Brittany

frontier visiting and making charters at Mont St Michael, St Jacques and Pontorson. However, Conan never witnessed a

surviving grant of King Henry in France. This may say something of their

relationship. Presumably the grant of Nantes to Henry is the one

referred to in the Meler chronicle, which misdates the event to 1159.

1159, Geoffrey Martel died [26 Jul 1158]. In

the same year Count Conan of Richmond recovered the city of Nantes: but

he only held it for a few days, releasing it to King Henry of England

about 3 October (the festival of S. Dyonis) in the same year.

Similarly, another compilation chronicle misdates the affair to 1157. This has:

After the death of Count Geoffrey of Nantes, the

brother of King Henry of England, in July, King Henry crossed over into

Normandy in August, and spoke with King Louis of the Franks on the

River Epte, about making peace and a marriage between his son, Henry

and Margaret, the daughter of the King of the Franks. Then they

went to Avranches (Abrincas), on 29 September (the feast of St.

Michael), where Duke Conan of Brittany restored the city of Nantes to

the king which he had invaded...

A second passage in the same chronicle, obviously compiled from another source, probably from Mont St Michael, has:

On the feast of St Michael [29 September], Count

Conan of Rennes and his Britons came with him to Avranches and restored

to the king the city of Nantes, with the whole county, valued at 40,000

Angevin shillings [£500]. From there the king came to Mont

St Michael...

Once again the trouble with hearsay chronicle evidence can be seen,

with the value of the county of de la Mee dropping by a full £250

as well as dates changing. Once again it has to be stressed that

the contents of any chronicle was only as good as its sources and the

ability of its compiler.

With good relations restored between duke and king at Michaelmas 1158,

there is little doubt that Richmond castle was also returned to Conan,

if it was ever taken away from him. Certainly there is no

evidence of the revenue of Richmondshire being used by the

Exchequer. Meanwhile King Henry, after taking Thouars castle,

roughly equidistant from Nantes to Poitiers, in a 3 day siege during

October, took King Louis on a tour of Normandy and then England.

Some disruption to the Richmond fee must have occurred this year for

the 1158 pipe roll does suggest that the vill of Great Abington (Abinton) was taken from Conan this year, for the sheriff of Cambridge accounted

for 20s paid from there to the Exchequer. Presumably this land

had been seized into the sheriff's hands, which then adds the question

as to why the other lands of Conan were not similarly mentioned?

In 1159 came the odd statement that the sheriff of Hertfordshire was

pardoned various sums by the king's writ. The last of these was

the debt of 30s 3d which remained in the land of the count of Brittany

and the earl of Warwick. The next year, 1160, the sheriff of

Norfolk and Suffolk was noted as owing 7s paid for mercy in Sudbourne

which remained in the land of the Count of Brittany. The same

year there was an unusual expense of 104s 2d for conveying wine to

Brittany. Was this a present to the duke? Quite clearly

these isolated references suggest some royal intervention in Conan's

lands, but do not necessarily represent hostility and similar entries

are to be found in the rolls concerning many other barons.

In 1160, King Malcolm of Scotland gave his sister Margaret to Duke

Conan of Brittany. Considering Conan's position as earl of

Richmond, this might be seen as a hostile act to Henry II, because as

recently as 1157 the Scottish border had been adjacent to Conan's lands

and Conan had presumably been responsible for maintaining his portion

of the Anglo-Scottish border. The marriage would also suggest

that Conan was in Scotland, or at least Richmond this year, as

presumably Conan came to Scotland to collect his royal bride, Conan

having a lesser political standing than King Malcolm. Meanwhile

King Henry spent all this year in France and went nowhere near Brittany

as far as can be ascertained. During this period Conan made

several grants to his English barons in Guingamp in Brittany that were

witnessed by his wife, Margaret. This may suggest that his

Richmond barons had supported him in his continental campaigns.

Margaret also made one grant at Guingamp in her own right, but

confirmed by her husband. This happened before 2 August 1167,

when Bishop Bernard of Quimper died. A charter of Conan's

supposedly witnessed by her at Quimper in 1160 is almost certainly a

forgery.

Duke Conan did not appear much in the pipe rolls, but in 1162 he was

fined and paid 4m (£2 13s 4d) scutage under Cambridge. The

same year on 2 February 1163, Conan was at Rennes when he made grants

to Savigny and the Templars in Brittany. In these he described

himself as duke of Brittany and earl of Richmond, a title he seemed to

use on many occasions. Another such undated charter was made at

Richemundiam and was witnessed by Ralph Fitz Ribald (d.1168+,

Middleham) and Alan the Constable (d.1201).

King Henry II (1154-89) returned to England in January 1163 after

Christmassing at Cherbourg. He remained progressing around

England and dealing with the escalating Thomas Becket crisis until

February 1165. A chronicle confirms that Conan was definitely in

Brittany during 1163:

Count Hervey of Leon, a most valiant soldier [he had

been earl of Wiltshire for King Stephen until disgraced in 1141], who

had fought many illustrious wars in England and in other places, and

had thereby lost an eye, was taken by treachery together with Guidomar

his son, and they were thrown back into prison at Castelnoec (Nini

castle); but Bishop Haymo of Leon, together with the soldiers and his

people, having taken arms, besieged the castle; to whom Duke Conan

Junior of Brittany, gave assistance and attended in person. The

castle was therefore attacked and taken by force, Count Hervey and his

son being freed from thence. But the Viscount of Fagi, together

with his brother and his son, who had perpetrated that trick, were

imprisoned at Donges (Donglas - a region between Nantes and Vannes),

and forced to perish by hunger and thirst. In the same year there

was a great famine in the same country.

Duke Conan was still in royal favour and was third witness of the

constitutions of Clarendon of January 1164 as Count Conan of

Brittany. This was the only time he witnessed a royal act.

Around the same time Duke Conan of Brittany and earl of Richmond made a

charter at Wilton, some 5 miles west of Clarendon, with several of his

colleagues from Clarendon, namely Earl Reginald of Cornwall (d.1175),

Earl Robert of Leicester (d.1168) and Bishop Bartholomew Bohun of

Exeter (d.1184).

In 1165 Count Eudes, Duke Conan's step father, was obviously also in

royal favour for he made a new fine, probably scutage for the Welsh

army, as he owed and paid 45s 9d this year under Devon as Count Eudes

of Brittany. Again this points to some form of power sharing in

Brittany. The same year in Yorkshire, Count Conan was recorded as

owing £227 10s, of which he paid £52 6s 8d, leaving a debt

of £175 3s 4d. Two years later in 1167 the king pardoned

the remainder. The same year his sokemen in Lincolnshire were

assessed for 100m (£66 13s 4d) as a gift of which they paid 50m

(£33 6s 8d) immediately and the remainder in 1166.

Conan would seem to have been in Brittany at this time, for that year a

royal army of Normans and Bretons under King Henry's constable, Richard

Hommet, at the king's bidding, took Combourg castle from Ralph Fougeres

(d.1194), who was holding it after the death of John Dol

(d.1162). The next year in 1165, it had been reported to the king

that the nobles of Brittany and Maine had been disparaging to Queen

Eleanor while the king campaigned in Wales during the summer.

Consequently in June 1166:

because... the nobles of the county of Maine and the

region of Brittany had obeyed the queen's commands less than they

should, and, as it is said, had bound themselves by an oath to defend

themselves in common if any of them should be injured, the king dealt

with them and their castles at his pleasure; and having collected

troops from almost all his power on this side of the sea, the king

besieged Fougeres castle, took it and destroyed it to the ground.

After this, Count Conan of Brittany and Richmond, granted the king the

marriage of his daughter Constance for the king's son, Geoffrey, with

the whole duchy of Brittany except for the county of Guingamp which had

come to him through his grandfather, Count Stephen. The king

received the homage of nearly all the barons of Brittany at

Thouars. Afterwards he came to Rennes and by taking possession of

that city, the capital of Brittany, he had seisin of the whole duchy.

And, as he had never yet seen either Combourg or Dol

he paid them a passing visit after they come into his hands.

This passage seems conclusive that Duke Conan granted Brittany away in

1166. However, the crucial word in this is that the grant

happened ‘after' the siege of Fougeres. The key is

therefore how long after, as again the passage has obviously been

written in retrospect. Possibly the answer lies in the Annales of

Mont St Michel which states:

King Henry contracted a marriage between Geoffrey

his son and Constance the daughter of Count Conan of Brittany.

Further, we know that Duke Conan was at Rennes this year with his

cousin, Ralph Fougeres (d.1194), the enemy of King Henry II

(1154-89). That year he confirmed the grant of Long Bennington,

Lincolnshire, to Savigny abbey in a charter which informed ‘all

his barons, sheriffs, mayors, justices, ministers, bailiffs and all his

faithful French and English men throughout England of the fact'.

This act was drawn up in the inner chamber next to the keep at Rennes

castle (in thalamo juxta turrim). That Ralph and Conan were

together during this year would suggest that Conan was in opposition to

King Henry. That Duke Conan became the man of Henry II in

Brittany is stated in his charter taking Begard abbey under his

protection as this was done at the petition of his lord and king and

his men. That king must be Henry II.

At September 1166, Count Conan was pardoned 25m (£16 13s 4d) in

Lincolnshire and paid nothing against his Yorkshire debt of £175

3s 4d. He also this year failed to hand in a carta for most of

his lands, although cartae may have been produced for his lands in

Cambridgeshire, Norfolk and Suffolk. Certainly in 1166 and 1168

the sheriffs of these counties entered returns for these knights.

Probably early in the reign of King John (1199-1216), possibly before

the death of Duchess Constance in 1201, a replacement carta was drawn

up. This was titled:

The Knights' fees in Richmondshire for which

scutage must be paid, both of the new and the old feoffment according

to the pipe rolls in the King's Exchequer.

This listed the

following fees, sometimes with where they were based.

|

Old Fees |

|

Lord |

Vill |

Fees |

|

Ralph Fitz Ralph (d.1177+) |

Middleham |

6 |

| Roald Constable (d.1158/1247) |

|

6½ |

|

Rollos who held of him |

|

6½ |

|

Alan Fitz Brian (d.1188) |

Bedale |

4 and a sixth |

|

Ralph Montchensey (d.bef.1185) |

the 2 Cowtons [North and East] |

1 |

|

Ralph Fitz Henry (d.1243) |

Ravensworth |

3 and a sixth |

|

Robert Musters (bef.1189) |

Kirklington/Kilvington (Kittelington) |

3 |

|

Conan Fitz Ellis (d.1218) |

Magna Cowton |

1 |

|

Conan Fitz Ellis (d.1218) |

Ainderby Myers & Holtby |

2 |

|

Conan Fitz Ellis (d.1218) |

Hutton Hang and East [Patrick] Brompton |

½ |

| camerarii |

Kilwardby, Askham, Appleby and Fencote |

2½ |

|

Hugh Fitz Gernagan (d.bef.1203) |

West Tanfield |

2½ |

| Steward |

Thornton |

2 |

|

Torphin Fitz Robert |

Manfield |

1 |

|

Picot Lascelles (d.1179) |

Scruton |

2½ |

|

Pincernae's |

Barden and in Cambridgeshire |

1 |

|

Thomas Burgh (d.1199) |

Appleton [Wiske?] and Hackforth |

2 |

|

Mowbray fee |

Masham (Massamschine) |

1 |

|

Henry Sutton |

Warlaby |

1 |

|

Robert Fitz Tenay |

Eryom |

1 |

|

fee of Munby |

Wycliffe |

1 |

|

William de la Mare |

Yafforth |

1 |

| Hervey |

Coverham and Ainderby |

1 |

| Charles |

Brignall |

1 |

|

Conan Aske |

Aske Hall and Marrick |

1 |

|

Alexander Fitz Nigel |

Wensley |

1 |

|

Alan Fitz Emeri |

Ainderby Viconte, Sutton [Grange or Howgrave?] and Sinderby |

2/3 |

|

Robert Tattershall |

West Witton |

½ |

|

Joklewini Neirford |

Newton Morell |

1 |

| Theobald Valoignes (d.1209) |

Rokewik |

½ |

|

Geoffrey Scales (Scalariis) |

Berford, Carlton and Stapleton |

¾ |

|

Pain Orbelynger |

Kerkan [Kirkham?] |

¾ |

| Gerneby |

Rousshotton |

4 parts of a fee |

|

Alan Ducis |

Tyngale |

4 parts of a fee |

|

Roger Mateham |

Eggleston |

6 parts of a fee |

|

Alexander Breton |

Colburn |

4 parts of a fee |

| fee of Hoton Longvillers |

|

4 parts of a fee |

|

Gilbert Gant (d.1242) |

Swaledale on both sides of the river |

4 |

|

Total Old Fees |

|

66 |

|

New Fees |

|

William Percy |

Milby and Easby |

½ |

|

Reginald Boterell |

East Witton |

1/3 |

|

Wigan Fitz Cades |

Hartforth |

¼ |

|

Thomas Fitz William |

Middleton |

1/3 |

|

Osbert Fitz Fulk and Odard |

Gilling West |

a sixth |

| Fee of Barningham (Bernyngham) |

|

¼ |

| Fee of Scargill |

|

¼ |

|

Geoffrey Hengham |

Multon [Malton?] |

1/8 |

|

Total New Fees |

|

2½+ |

|

Total Fees |

|

68½+ |

It was also recorded that castle guard was accounted for in money on

the basis of ½m (6s 8d) per fee. The totals there were

given for each 2 month period of service and totalled £20 6s

3¾d. Sixty eight and a half fees multiplied by half a mark

equalled £22 13s 4d against £20 for just 60 fees, so

something had been misrecorded in the table, or there was a dispute

about service owed.

This table was followed by a second return which recorded the castle

guard due from outside Richmondshire. This itself was divided

into 2 with the first portion relating to the area that lay between

‘the Well Stream (Wellestre) and the Norman Sea' and covered

Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Hertfordshire and Essex. The

second portion covered Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and parts of

Yorkshire and both were again divided into 2 monthly sections.

|

During April and May |

| Lord |

Vill |

Fees |

|

Earl Aubrey (d.1194 or 1214) |

Caenby and Aythorpe Roding (Roenges) |

3 |

|

Alan Bassingbourn |

Wimpole, Cambridgeshire of Earl Aubrey |

1 |

|

Theobald Valoignes (d.1209) |

Ditton [Green], Cambridgeshire |

3 |

|

John Fitz William |

Stanton |

1 |

|

Robert Novill |

Toftes or near |

1 |

| Simon |

Brunne or near |

1 |

|

Bertram Verdun (d.1192 or 1217+) |

in Hertfordshire |

½ divided as below |

|

[John Bassingbourne |

Hoddesdon |

a third of the half fee] |

|

[Peter Hormade |

Hormead |

a third of the half fee] |

|

[Walter Fitz Bonde |

Reed |

a third of the half fee] |

|

June and July from Norfolk |

| Ralph Fitz Robert (Middleham, d.1252) |

Hethersett (Hedersete) |

6 |

|

Robert Fitz Roger |

Lins [Lyng?] |

1 |

|

Geoffrey Nerford |

Narford |

½ |

|

Robert Holm |

Mileham and Swaffham |

1 |

|

William Pincerna held of Robert Fitz Robert |

Rougham (Ruhham) |

|

|

William Montchesney |

Foxley and Claie [Cley next the Sea?] |

2 |

|

Robert Tattersall for which Hamo Fitz Burd answers |

Horningtoft |

1 |

|

Ralph Lenham |

Redhalle and Fring (Rninges) |

4 fees less 20d |

|

August and September in Cambridgeshire |

|

Robert Hastings of Earl Aubrey |

Lenwade (Lanwad) |

1 |

|

Ralph Rameis |

Burwell |

1 |

|

Gunnar Fitz Warner |

Wiere |

1 |

| Thomas Bure |

Bury |

2 |

|

Roger Fitz Richard |

Weston |

¼ |

|

Theobald Valoignes (d.1209) in Norfolk |

Harling (Hielinge) |

1 |

|

October and November in Essex |

|

Richard Ispania of Earl Aubrey |

Finchingfield and appurtenances |

3 less 2s |

|

Robert Furnels |

Bereham and Harling in Cambridgeshire |

7 |

|

The Chamberlain's Fee |

|

6 as divided below |

|

Robert Vavasour |

Melketon |

1 |

|

Hugh Craweden |

Swaffham |

1 |

|

Everard Francis |

Ballingham and Swaffham |

2 |

|

William Fitz Aliz |

Oxecroft |

1 |

|

Luke Banes |

[one fee divided as] |

¼ |

|

[Fulk Fitz Theobald |

|

18d] |

|

[Henry Fitz Hervey |

|

18d] |

|

[Roger Sleeveless |

|

18d] |

|

[Lady Avice |

|

18d] |

|

[Walter Cormeilles |

Great Wilbraham (Wilburham) and Wendy |

18d] |

|

Lady Agnes Blund |

Whaddon |

½ |

|

All Saints Term (1 November) |

|

Philip Cheshunt |

Cheshunt |

¼ |

|

St Andrew's Term (30 November) in Suffolk |

|

Earl Roger |

Saham ad stagnum |

2 |

|

Geoffrey Bromfield |

[Bramford?] Bromfield and appurtenances |

5 |

|

Geoffrey Bromfield |

Nettlestead (Netlestede) |

2 |

|

Robert Quaremel |

Bures (Bure) and Blakenham |

1 |

|

Norman Pesehale |

Westerfield |

¼ |

|

Simon Tunderle of Earl Aubrey |

Dodnash (Dodenes), Hintlesham (Hintesham) and Duston |

1 |

|

Theobald Valoignes (d.1209) |

Parham and appurtenances |

5½ |

|

William Gikel of Earl Aubrey |

Norton [Heath?] in Essex |

1 |

| of fee of Earl Aubrey in Cambridgeshire |

Wickam Market |

3 |

|

[Walter de la Hay |

Wicham |

1½] |

|

[Walter Russel |

Wicham |

1½] |

|

Simon le Bret and John Lanvalein |

Great Abington |

1 |

|

Purification Term (2 February) |

|

Godwin Nerford |

Narford, Chediston (Sidesterne) and Westerfield |

1½ |

|

Alan Benington |

of Chamberlain in Holland |

1 |

| Ralph Fitz Stephen |

Skeffling (Scefning) in Holland |

½ |

|

Brain Fitz Alan (in June) |

Bicker (Bicre) in Holland |

1 |

|

Roger Lascelles in October and November |

Fulstow,

Aylesby and Swallow in Lincolnshire |

2½ |

|

Osbern Fitz Neal |

Fulbeck, Leadenham, Stokes and Herkerby and appurtenances in Lincolnshire |

3 |

|

Robert Sutton |

Sutton and appurtenances in Nottinghamshire |

3 |

|

Hugh Wigetoft as heir of Grip |

Wigtoft, Reddie and Kirkton |

3 |

| William Grenesbi |

5 parts in Grainsby and the rest in

Little Hutton in Wycliffe (Ruhoton) in Richmondshire |

1 |

|

Roger Trehanton |

Lee and Burton by Trent |

2 |

|

Simon Horbelinge |

Horbling |

¾ |

|

February and March |

|

Conan Fitz Ellis |

Holbeach, Welton le Wold (Welleton) and Rilvingholm |

2½ |

|

Eudo Mumby |

Mumby and soke |

4 |

|

Ralph Lamara |

Cadney (Kadeneia) and Kelsey (Kelleseia) |

3 |

|

Joscelin Noville |

Rigsby (Riggesbi) |

1 |

|

Rolleston |

1 |

|

April and May |

|

Thomas Muleton |

Skirbeck (Scirebec) |

1 |

|

Simon Chanci |

Swinhope (Suinhop) |

1 |

| Alan Creun, the son of Grimketel, the son of Sired and the son of

Toli |

Benington and Birk...., Broughton House

(Brochton) and Gelston (Geveleston) by Leadenham in

Holland |

2 |

|

Lisiard Musters |

Chinston |

1 |

|

Wr.... |

|

1 |

|

Catebi |

1 |

It is odd that Duke Conan is not mentioned at all in 1167 when Henry II

campaigned through Brittany at the end of August to attack Viscount

Hervey of Leon (d.1168) and his son Guidomar, who were causing problems

during the war between King Henry and King Louis. After Hervey's

death, his son, Guidomar, soon joined the rebels fighting against Henry

II. Duke Eudes, Conan's step father, was also back in the field

with Roland Dinan (d.1186) in opposition to the king. Peace was

subsequently made around the beginning of October 1167 with Henry

retaining half of Dinan and Roland the other half. Noticeably

missing from the short list of combatants in these campaigns is Earl

Conan of Richmond. All that is recorded of him this year is that at Michaelmas 1167, the

sheriff of Yorkshire accounted for ½m (6s 8d) paid from Count

Conan's vill of Donington, Lincolnshire.

Diceto dates the following event to 1168:

Since kings ceased to preside over Brittany, 2

counts began to rule in their places. But since 'all impatient

power' will always be 'consorted', they often afflicted themselves with

various dissensions. Conan at last obtained both the counties by

hereditary right, and, as fate would grant, he left an heiress by the

sister of the king of the Scots. Then the king of the English

gave her to his son Geoffrey to wed, and being anxious to establish

peace here and there throughout Brittany, he won over the clergy of

that land and the people.

Diceto was a contemporary of events he recorded, so we must presume

that this is what happened. However, once more this precis is

obviously written in hindsight and covered many years, not just the

year 1168. As Conan had a legitimate son, William, this agreement

seems less than honest on the part of the king and was obviously an act

of political power. Certainly many nobles accused Henry II of

coveting their properties.

Duke Conan was with Henry II on 24 March 1168 when he witnessed a royal

charter at Angers as Count Conan of Brittany. Soon after this,

probably in May 1168, King Henry marched all the way through Brittany

taking Josselin and Auray (Abrahi) castles north of Vannes.

Before the truce [with King Louis] was given, the

king of the English had admonished Viscount Eudes of Porhoet, who had

hitherto been called by the name of the northern count and to whom he

had contributed so much in goods that he should come to his service and

assistance which he himself refused, while certain others of the

Bretons confederated with him, namely Oliver, the son of Oliver Dinan

and Roland, his cousin. And so the king, having not undeservedly

attacked them in anger, beginning at the head, that is, with Eudes,

ravaged and burned their land, first of all destroying the castle of

Josselin (Lucenni), which was the most important he had. He [the