Norwich

Norwich seems to have been an ancient defensible site, surrounded

as it was by the River Wensum on 3 sides with the castle site

controlling a spur across the neck. In this manner it was similar

to Durham and Shrewsbury

castles. Occupation of the site is testified by numerous finds of

Roman coins and urns in the vicinity, but there is as yet no trace of

any buildings. Saxon habitation also occurred here with 2 more

churches being evidenced by excavation in the castle vicinity, while

coins were struck at Norwich from the reign of King Aethelstan

(925-41). As this king decreed that every burgh should have a

mint, this probably places the early fortifications of the city back to

that era or earlier. The place was important enough to be the

first apparent victim of Swein Forkbeard's first attack of 1004.

Despite this, there is little evidence of fortification here prior to

the arrival of the Normans, although a possible Viking enclosure has

been noted just north of the River Wensum. In the thirteenth

century Norwich was reckoned to have been the capital of East Anglia in

585.

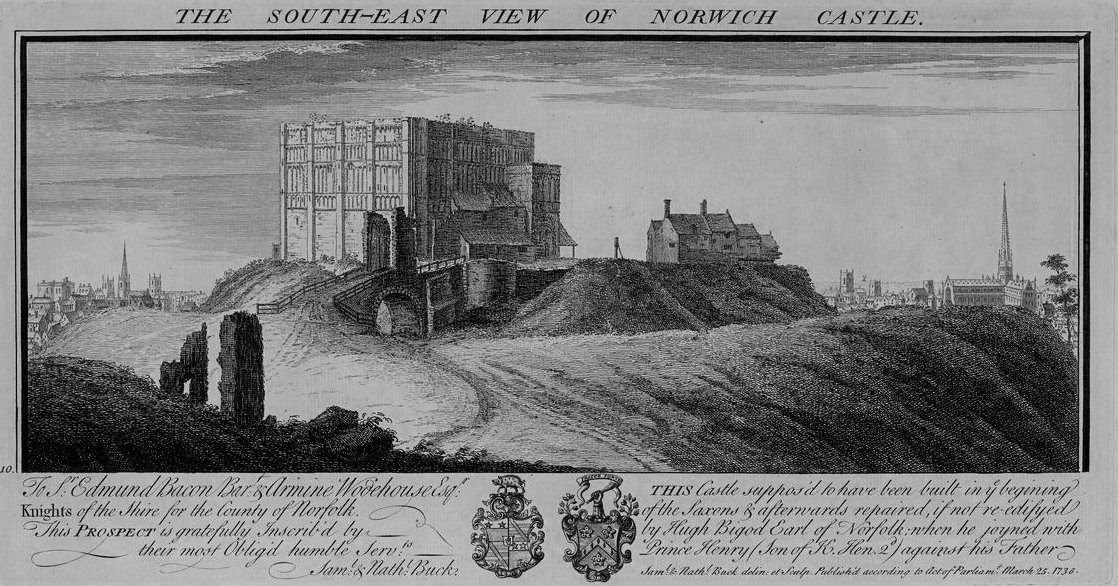

Norwich castle was founded within 2 years of the battle of Hastings in

1066, as William's army moved north to secure control of the bulk

of England. Certainly the site was ideal for the occupation of

East Anglia which occurred in 1068. Consequently a date of 1067

has been suggested for the construction of the castle, strategically

placed overlooking the river valley as it loops around to the north and

east. Indeed William of Poitiers, the Conqueror's chaplain,

recorded that when King William left England for Normandy in 1067 he

placed William Fitz Osbern in the city of Guenta

which lay 14 miles from the sea which separated England from the

Danes. In this city he built a fortress/garrison within the walls

(hujus quoque urbis intra moenia munitionem construxit)

to overawe the district to the north. Presumably this marked the

beginning of the Norman castle. However, his description of it

lying within the burgh defences of Guenta Icenorum

might suggest that the first castle lay at Caistor St Edmunds, some 3

miles south of Norwich castle where the Roman town defences still

survive. Alternatively, the possibility has been advanced that

Guenta was actually Winchester - Roman Venta Belgarum, equally it might

just be Venta Silarium - Caerwent in Gwent, but that is surely too near

the coast and too far from the north of the English kingdom. To

support the Norwich identification, there is no evidence that Fitz

Osbern held Winchester, but Hugh Grandmesnil (d.1098) was recorded as

the first governor of Hampshire by Orderic Vitalis, admittedly writing

a generation later. Further, before 1074, Ralph Gael was earl of

East Anglia, which would make it eminently possible that Gael was Fitz

Osbern's successor to Norwich. If this is so it would therefore

appear that Poitiers had blundered over the name of Norwich, naming the

old Roman centre, rather than the newer burgh which replaced it.

Certainly Norwich seems to fit the description better than Winchester

for opposing the Danes and controlling the north of England. To

add to the confusion both Norwich and Winchester could be argued to be

some 14 miles from the sea, depending on where the coastline actually

was during this period.

To the north-east of Norwich castle lies the cathedral which was

founded in the last years of the reign of William Rufus (1087-1100),

while to the west lay what was known as the castle fee (an area of

about 23 acres). This became the French borough and was defended by the later city defences. Excavation

has shown that the castle was built upon Saxon deposits which seem to

date mostly from the tenth century onwards and show signs that much

craft or industry was undertaken in the city as well as grain

storage. Found partially under the later southern bailey rampart

was evidence for a timber stave church and a graveyard. These

were in use from the late tenth century until the building of the

castle and contained at least 130 burials. Another church and

cemetery lay beneath the north-east bailey, while it has been suggested that another possible

bailey lay under the northern part of the site.

The evidence above suggests that Norwich castle was founded for William

the Conqueror (1066-87) in what was probably the fourth largest town in

England. The fortress was certainly operational in 1075, when

Earl Ralph Gael of the East Angles, rebelled against William the

Conqueror. After he married Emma the sister of Earl Roger of

Hereford at Exning in 1075 ‘he then led that woman to

Norwich. That bride-ale there was death to men'. As earl of

East Anglia, Ralph undoubtedly held Norwich castle for his king.

However, his rebellious plot was betrayed by Earl Waltheof (d.1076) and

the regent, Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury (1070-89), sent troops

against the rebels. Earl Ralph, the plot having been uncovered

before the conspirators were ready, attempted to rally support.

In this he failed and his co-conspirators of the Welsh Marches were

defeated and dispersed. Meanwhile Earl Ralph had been countered

by Bishop Odo of Bayeux and Bishop Geoffrey of Coutances marching on

Cambridge. Ralph then retired on ‘his castle' of Norwich

which he turned over to the custody of his wife, Emma Crepon, and his

knights, while he himself took ship probably for Denmark to raise

support, before he fled to his homeland of Brittany. These

actions resulted in a siege of Norwich castle which ended when the king

proclaimed peace and allowed the countess and her men to follow her

husband abroad. Ralph ended his days fighting in the Holy Land.

After this action, Norwich castle reverted to royal control and

Lanfranc announced to King William that the fortress had been

surrendered according to the terms agreed and that it was now occupied

by Bishop Geoffrey of Coutances (d.1093), William Warenne (d.1088) and

Robert Malet (d.1105+) with a force of 300 serjeants (loricati) with

crossbowmen and many engineers (artifices machinarum).

Accordingly by the Autumn of 1075 when all the Bretons had left,

Lanfranc reckoned the country as peaceable as it had ever been.

The arrival of many engineers could well suggest the start of a massive

building campaign, perhaps that which led to the building of the

keep. Such an interpretation of building work may also explain

the royal notification of 1082 that Abbot Simon of Norwich was to be

quit of garrison duty at Norwich which he had conducted and

observed. Possibly the keep could have been built in the years

1075 to 1082 and this marked its completion. The idea that the

keep ‘is undoubtedly a work of the twelfth century' seems only to

date from the eighteenth century and is mainly based upon comparison

with other undated keeps, namely Castle Rising, Hedingham and Rochester.

By the time of the Domesday Survey of 1086 Norwich was one of some 50

odd castles explicitly mentioned in the survey. The Domesday entry recorded

that the building of the castle in a pre-existing settlement

necessitated the destruction of existing properties. At Norwich,

some 113 house sites were occupied by the site of the castle, the

actual survey stating:

In this land Harold had a soke, there were 15

burgesses and 17 mansures (measures of land) of waste which are

occupied by the castle and in the burgh 190 empty mansures which were

in the soke of the king and earl and 81 occupied by the castle.

Excavation has shown many earlier post holes of buildings destroyed by

the castle construction as well as the disturbance and removal of

Anglo-Saxon cemeteries. Quite clearly large scale building works

had gone on.

Only 2 years after the survey, in 1088, the castle went to war again. In that year Bishop

Odo of Bayeux (d.1097), Bishop Geoffrey of Coutances (d.1093), Earl

Robert of Mortain (d.1090), Earl Roger of Shrewsbury (d.1094) and all

the great men of country with the exception of Archbishop Lanfranc

plotted to overthrow King William Rufus (d.1100) and hand the kingdom

over to Duke Robert of Normandy (d.1134). To aid this project

Roger Bigod (d.1107), who had held Framlingham from Earl Hugh of

Chester (d.1101) in 1086, seized Norwich castle and devastated the

county in the name of the rebels. ‘One of them was called

Roger, who ran away into the castle at Norwich and still did worst of

all over the land.' However the rebellion failed, but Bigod

managed to make his peace with the king who resumed control of his

fortress.

Soon after 1094 it is alleged that work began on both the construction

of the cathedral and the castle keep. However no real documentary

evidence supports this claim which seems to be based upon a single act

of Rufus dated sometime between 1091 and 1096 and the comments in later

chronicles that this is when the transference of the bishopric began. The act of

Rufus notified Humphrey the Chamberlain, Ralph Passelewe, Odbert and

all the people of Norfolk and Suffolk that the king had granted Bishop

Herbert of Norwich (1091-1119) all the lands that had been viewed by

Bishop Walchelin of Winchester, Ranulf the Chaplain and Roger Bigod

(d.1107) to allow the bishop to ‘make his church and houses for

himself and his monks at Norwich castle (Norwyc castrum)'. This

act marked the move of the bishop's see from Thetford to Norwich as is

related in the Foundation History of the cathedral that states the

church was built beside Norwich castle at a place called Cowholme

(locum apud Norwicense castrum vocatum Cowholme) and copies the above

notification of Rufus. Such evidence says nothing of castle keeps

and only confirms that the castle was standing at this time and by the

language suggests that the fortress included the entire bend of the

river. A later source writing of the year 1133 noted that the

move had been partially sanctioned as long ago as 1075 and that Bishop

Herbert of Thetford had been instrumental in the upgrading of Norwich

to a bishopric. It was he who had spent much money in purchasing

‘a considerable portion of the city of Norwich and having pulled

down the houses and cleared a large space of ground, built a very find

church upon a beautiful site overlooking the River Wensum (Gerne)'.

After the death of Rufus in August 1100, King Henry I (1100-35) was

recorded in the castle during 1103, 1106, 9 May 1108 and 1122. On

the latter occasion he spent his Christmas in Norwich which included a

ceremonial crown wearing. The king also sent prisoners to the

castle, as was standard practise at the administrative centres during

the middle ages. During 1101 it is said to have been recorded

that stone masons working on Norwich cathedral were also fabricating

windows for the keep basement. At September 1130 it was recorded

that the bishop of Ely owed the massive sum of £1,000 for the

right to perform his castleguard in the isle of Ely rather than at

Norwich castle as he formerly did. Of this sum he paid £364

and owed £736. As Ely was some 50 miles from Norwich the

bishop obviously thought the large fine was worth paying.

Similarly St Benet's Holme had been exempted from castleguard at

Norwich castle by Henry I, although his charter was later apparently

repudiated by Henry II. During this same early period the knights

of Bury St Edmund's abbey were recorded as being accustomed to pay

their service at Norwich castle. Quite obviously the number of

knights who owed service at the fortress shows that this was a major

fortress in the kingdom with a knight force possibly similar to that

owed at Dover where the Dering Roll suggests that 324 knights owed

service to Constable Stephen Penchester of Dover (d.1299). Fees

owing at Norwich were probably well over a hundred.

In April 1136, allegedly on hearing a rumour of King Stephen's death,

Hugh Bigod (d.1176) seized Norwich castle and refused to relinquish it

until Stephen appeared in person to disprove the rumour. King

Stephen (1135-54) was apparently back in Norwich in May 1140 and soon

after gave the castle to Hugh Bigod when he made him earl of Norfolk

before 2 February 1141. Hugh proved a disloyal earl, so in or

soon after 1148 the king passed Castle Acre, Castle Rising,

Lewes and particularly Norwich castle to his son, Count William of

Mortain (d.1159). This act was partially recorded in King Stephen's and

Henry Fitz Empress' agreement of 1153. Possibly this was done

when the king came to Norwich, probably in the period 1146-48 when the

Jews complained to him according to Thomas Monmouth, concerning the

killing of one of their number by a local knight. King Stephen

and his heir, Eustace, were certainly in Norwich during the period

1147-53 and the king alone was there in the year November 1153 to

October 1154.

Despite Count William of Blois (d.1159) being confirmed in his lands during 1153 he was subsequently stripped of Norwich castle by King Henry II

(1154-89), when he returned from France in the spring of 1157.

However, although William surrendered both Norwich and Pevensey castles to

the king, he was allowed to keep all the land his father had granted

him. Some time earlier King Stephen (d.1154) had remitted the

castle guard of 40 knights due at Norwich from the monastery of Bury St Edmunds. In

1158 it was recorded that the sheriff of Norfolk had knights in Norwich

castle who had cost £51 12s to maintain. Presumably these

had been stationed there from the time when King Henry had resumed the

castle in 1157 and spent £20 on munitioning the fortress.

Similarly in 1158, knights in the Bigod castle of Framlingham had cost

the king £16 18s, while the burgesses of Norwich were recorded as

owing 300m (£200) of which they paid £19.

As no accounts appear in the pipe rolls for royal building works at

Norwich it is readily apparent that the keep was built before the reign

of Henry II (1154-89). Early in his reign the king also issued a

charter in favour of Norwich which restored the status of the city to

that which it held in the time of Henry I (1100-35) whereby he urged

those who withdrew ‘from their customs and scots' to

‘return to their society and custom and follow their scot because

I quitclaim not one of them...'. Quite clearly King Stephen's

actions had quite dramatically changed the equilibrium of the city and

this was not to the new king's perceived benefit.

In 1161 the burgesses of Norwich paid 10m (£6 13s 4d) which

was spent on works to the castle. In 1166 the sum of 78s 8d was

spent on Norwich jail which may have been within the castle precincts,

if not within the keep itself. For some reason the castle was

munitioned in 1168 at a cost of £10. Presumably this was

due to unease in the kingdom over the Becket dispute. In 1171

catastrophe struck Norwich when the city and cathedral were burned, but

no mention was made of the castle which presumably survived the

disaster. Certainly nothing seems to have been spent on its

repair.

In 1173, garrisons were put in Eye, Orford and Thetford

castles, which were obviously all in the king's hands. At Norwich

castle the garrison was supplied by 100 loads of wheat at £8 11s

1d, 100 bacons at £9 5s 11d, 26s 8d worth of salt, 74s 4d worth

of iron, 3 handmills at 3s, rope at a cost of 3s 4d and finally cheese

for 27s 6d. At the same time £20 4s 8d was accounted for

the repairs made to the wood and palisading of the bridge as well as 3

brattices. A force of 5 knights was also placed in Norwich for 20

days at a cost of £6 15s as well as an unnumbered force of

knights and serjeants for an unspecified time, but at a cost of

£33 6s 8d. Possibly this was the same 5 knights and

probably their 10 accompanying serjeants for there was also a payment

for 5 knights from Norwich receiving 113s 4d for 34 days service.

This garrisoning was obviously necessary due to the Young King Henry's

actions. He had been crowned king of England in

1170, but King Henry II (1154-89) had refused to let any power fall

into his son's hands. Consequently, at the urging of his mother,

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204) and other disgruntled aristocrats, the

Young King Henry III (d.1183) was exhorted to rebel and seize power

from his father, Henry II. The result was the young king's war

(1173-74). At the commencement of this the young king granted away

many royal estates to buy the allegiance of other aristocrats. To

Hugh Bigod he granted all the honour of Eye and custodianship of

Norwich castle. This explains the elder king's actions repairing

and garrisoning castles in East Anglia this year. The repairs

carried out to Norwich castle bridge has recently been claimed to show

that the surviving stone bridge existed at this time. However, as

there must have been several bridges to cross the numerous ditches such

an assumption, especially that this was a stone bridge referred to, is

ill-justified.

In 1174 further moneys had been put against Norwich and its castle

during the war. Philip Hastings had advanced £20 to 20

knights resident in Norwich castle and £6 4s 4d for the serjeants

there. On top of this Hugh Cressy, the custodian of the fortress,

received £21 13s 4d for wheat from the measurement (mensuram) of

Norwich as well as 200 cheeses for 100s, 100 loads of salt for

£20 as well as 38s worth of iron. Some repairs were also

carried out at the castle costing £11 18s. Philip Hastings

also received a further £20 for leading his knights from Norwich

castle against the Flemings who were at Bungay and Framlingham as well

as for sending 500 carpenters to the king at Seleham at a cost of 66s

8d. These were obviously needed for the king's coming assault on

Framlingham castle, which was cancelled on 25 July when Earl Hugh came

to Seleham and surrendered to his king. In 1175 Geoffrey Fitz

William rendered account from the honour of Giffard for garrisoning

Norwich castle with 71 loads of barley and 10 loads of iron and 15

loads of fish and 38 loads of oats at a cost of £6 14s and also 5

loads of wheat at 21s 8d. The same year one Roger repaired

Norwich castle at a cost of £13 8s 4d. He and the 2

engineers, Henry Bello [Fago] and Reginald Benedict, also accounted for

unspecified works there costing £7 6s 8d. These undefined

repair works are what would normally be expected at a castle being

brought into the forefront of its military defensibility.

The precautions taken at Norwich were obviously necessary for this year

the long awaited attack finally arrived. Late in May 1174, Hugh

Bigod, with a force of 318 Flemish knights who had just landed at

Orwell (Arewellam) together with his own men advanced into Norfolk to attack

Norwich. During their assault he burned the town on 18 June

before returning to his own castle [presumably Framlingham] with many

captives. Despite modern claims to the contrary, no original

source states that he took Norwich castle. This proved the high

point of Bigod's war and soon afterwards he was forced from Framlingham

to surrender by Henry II in person that July. After this fighting

was over, further unspecified repairs were carried out to the castle in

1176 under the supervision of Henry Bigod (Bigart) and Henry

Bellofago. These cost £20 2s, while a further £20 was

spent under the view of Nicholas Fitz Randolf, John Curry (Cureie) and

Ralph Sergeant. This was probably to repair the castle from the

attack of Hugh Bigod in 1174, as this same year the burgesses of

Norwich were reported as owing £16 on account of them having

allowed the destruction of their city in time of war.

After this action maintenance of the fortress seems to have been

ignored until 1184 when 45s 6d was spent on the jail and £4 on

mending the houses and bridge within (infra) Norwich castle.

Another 43s 4d was spent on the jail houses the next year, 1185.

The final act of King Henry II in relation to Norwich castle was in

allowing for the castle constable, Harvey Fitz Peter, to spend 42s on

repairing the castle hall. Presumably this was the hall within

the keep.

By the mid twelfth century Jews were well settled in Norwich, close to

the protection of the castle and its constable, Sheriff John Chesney

(d.1146). To many, especially Bishop William Turbeville

(1146-74), they were not welcome. One consequence of this was a

cult founded in Norwich in the wake of the murder of a young boy,

William of Norwich, around 22 March 1144. The bishop was largely

responsible for the blaming of the Jews for this crime, despite

opposition from his own clergy. In Lent 1190, the Jews throughout

England were attacked and their loan documents destroyed. On 6

February (Shrove Tuesday) these riots spread to Norwich and many who

did not reach the safety of the castle were put to death by the crowds.

With the disturbances of King Richard's reign (1189-99) a garrison was

placed in Norwich castle after it, Eye and Orford castles were repaired

in 1192 at a cost of £25 8s 8d. The 1193 pipe roll listed a

garrison of 25 knights who remained at the castle for 40 days at a cost

of £50. They were supported by 25 horse serjeants at

£16 13s 4d and 25 foot serjeants at £8 6s 8d. These

forces were undoubtedly raised against Prince John and his allies who

attempted to subvert the kingdom that year. After Richard's death

in 1199 King John took over the castle and repaired it at unknown cost,

but spending 40s on stone for his works there in 1205. Works may

have continued the next year, 1206, when William Gisnei owed 2 palfreys

to be used for the repair of the castle of Norwiz, although he was

pardoned one horse and still owed the other. The same year

£35 were spent on the castle works under Elias Diss and William

Malcuilvert. In 1209 it was recorded that William Blund and his

heirs paid ward at Norwich castle.

In May 1216 the Legate Guala (d.1227) arrived in England and soon

afterwards Prince Louis Capet (d.1226) and his army set off from London

into East Anglia, laying waste the towns of Essex, Suffolk and finally

Norfolk. In the centre of that province they found Norwich castle

ungarrisoned and seized the castellan, Thomas Burgh (d.1235), the

brother of Hubert the justiciar (d.1243), despite this castle and Orford having been granted to the rebels by Hubert Burgh in order to gain a short truce. The rebels then retired on

London by way of King's Lynn. The fortress was returned to Henry

III

(1216-72) in 1217 and in 1221 the regency council appointed a baron

of the exchequer to account with Philip Marmion for repairing and

victualling the castle. With this the castle settled back into

being a seat for administrative business in the county. On 2

January 1234 the king ordered William Bardulf not to be distrained as

he was absent from the garrison of Norwich in the king's service in the

Marches of Wales.

By 1242 it was noted that the sheriff of Norfolk was in charge of

garrisoning both Norwich and Orford castles. While in 1248 a

Welsh monk who had murdered Prior Thomas of Thetford was imprisoned in

Norwich castle keep (turri Norwicensis oppidi). The civil wars of

1264-67 seem largely to have passed Norwich by, but Sheriff Nicholas,

coming from the castle with his brother Thomas Despenser, suffered a

broken leg from a misplaced kick at a family enemy in June 1264.

This led to his death and a court judgement of death by

misadventure. On 31 May 1267 there was a scare that the

disinherited barons at Ely were coming to sack the city, but this

attack never materialised. The keep however remained as a prison

and on 8 May 1308, the sheriff of Norfolk to pay their dues to Rhys the

brother of Maelgwn and Gruffydd his brother and the son of Rhys ap

Maredudd in who were held captive in Norwich castle. By this time

the fortress was apparently obsolete. Before 1221 the city had

begun to encroach onto the south and east baileys. These were

used by the townsfolk for grazing and occasional commerce, as well as

for dumping rubbish and quarrying for building materials.

However, the main entrance into the castle, in the form of the main

bridge, was repaired in 1267 and 1328. With the building of the

town walls from 1253 the castle baileys seem to have become

increasingly irrelevant. The southern bailey appears to have been

early encroached upon and both baileys were granted to the city by

Edward III on 9 August 1345, with the Crown maintaining control of the

castle with its moat (presumably the main mound with the keep within

the inner ward and the bridge and south gate) and the shire house

within the south bailey. The rest of the outworks in the castle

fee were handed over to the city. Despite this, by 1390 the

castle was in a bad state of decay. It never saw action again,

but remained as an administrative centre and prison. In 1825 a

new jail was built against the north and east sides of the keep which

was converted into the prison hospital.

Description

The castle was once a large complex, as would befit the caput of a

shire. Around the castle and its two baileys and extending beyond

them, was the castle fee, an area thought to cover 23 acres. It

has been guessed in many modern accounts that alterations were made to

the defences ‘between

1094 and 1122' and that these included the insertion of a new south

bailey ditch and the recutting of the outer ditch to the north-east

bailey, a defended meadow, as well as raising the main mound in height

before building the keep. Despite these claims, excavation within

the south bailey produced no evidence of wooden structures or defences

although it is widely stated that Norwich castle began life as ‘a

timber motte and bailey castle'. It is consequently possible that

bratticing surrounded the early site while a relatively low wall was

built around the mound top. Such a defence would be quite

sufficient for the early days of conquest.

Before the castle was built, it would appear that Anglo-Saxon Norwich

was made up of 5 villages which had, before 1066 and probably before

1004 when it was sacked by Swein Forkbeard, merged to form the borough

of Norwich. With the coming of the Conqueror's troops, probably

early in 1067, various buildings were cleared from the site and a new

castle laid out. Domesday Book appears to list some 1,358

households in the city and refers to some 113 properties being wasted and enclosed

by the new? defensives. This set the castle in one of the largest

settlements in the country. Other castles of various designs were

placed in several Saxon towns, viz, Caerwent, Chester, Hereford, Lincoln, London, Pevensey, Portchester, Rochester,

Shrewsbury, Winchester, Worcester and York. The site selected at Norwich was a natural ridge

overlooking the River Wensum to the east, while a small stream, the

Great Cockey, lay to the west. Norwich remained the only royal

castle in the 2 co-joined counties of Norfolk and Suffolk until the

construction of Orford in 1165. The fact they were cojoined

probably meant that Norwich was the only royal administrative centre

deemed necessary for the district until 1165. Further inland lay

the great royal administrative centres at Cambridge/Huntington and

Colchester.

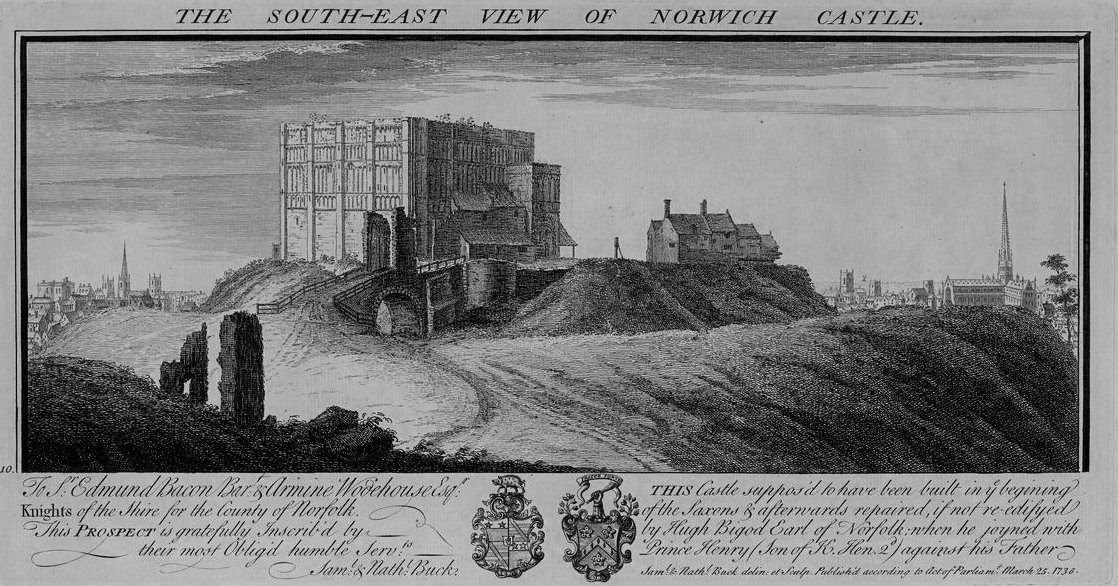

Norwich castle consisted of a great mound which supported the keep, which

itself was surrounded by an inner bailey. As such this mound was much

larger and flatter than a traditional inverted pudding bowl motte and

should therefore be referred to as a mound rather than a true

motte. The mound ditch survives only to the south,

where it would appear to have been originally much wider.

Excavations in 1906 found that the ditch bottom around the mound at its

greatest depth seems to have been about 74' beneath the berm and that

it was cut into solid chalk. The mound was also found to be

'totally artificial' and between 35' and 40' high, while the slope varied

from 20 degrees to the east to a more normal 40 degrees for most of the

structure. Its large size gave it a summit diameter of between

300' and 360' with a basal diameter of between 440' and 480'. As

such it is clearly a raised inner ward mound, rather than a typical

conical motte. Reassessment

of the data shows a turfline covered with 11' of loam, then thin layers

of chalk, loam and chalk again. Below the turfline was 5' of sand

overlying 9½' of sand which was probably all natural and lying

on the chalk bedrock. Various pits were found Saxo-Norman pottery

were found at depths of between 13' and 27'. On the motte top

similar pottery was found at depths of 5' and 15'.

To the south of the mound was a small quarter moon

shaped barbican, joined to the mound by an early bridge who's remnants

are incased in nineteenth century masonry. Beyond this was a

semi-circular bailey which was probably a primary build with the

mound. By the late medieval period this no longer marked the main

entrance to the castle as the church of St John to the south of the

castle was known as St John at the postern gate (januam) in 1453.

To the north and east of the mound was another quarter moon bailey

which might be primary, although current opinion seems to be that it

was a slightly later addition. All of these earthworks were

defended by ditches, some of which have been excavated, especially to

the south.

The main defence of the masonry castle stood on the summit of the

Castle Mound. It was polygonal in plan and included the

keep within its defences. All that remains of these defences are

the foundations of 2 D shaped towers that flanked the entrance over the

bridge to the south. These towers formed a standard twin towered gatehouse which contained a

rectangular room in each tower, entered from the north end of the gate

passageway. In plan it seems more a rectangular gatetower with

two ¾ round turrets at the exposed corners, rather than a true

thirteenth century gatehouse. As such it could well be earlier

rather than later in its construction date. The nearly square keep is set towards the

south-west corner of the mound and is bounded to north and east by the

nineteenth century prison which has alternating short and long sides,

like a square with chamfered off corners. This almost certainly

does not overlie the original masonry defences which almost certainly lay at the edge of

the berm and not well back as the prison wall does now. This plan

is confirmed by the position of the south twin towered gatehouse in

relation to the south bridge. The walls on either side of this

tower clearly show that the wall was on the downward slope of the

current berm and not 15' to 20' behind it, like the current prison wall.

The Keep

The Keep

The great stone tower keep is one of the largest in England, even

though it is only 2 floors high. It is almost square being

some 95' long by 90' wide and rising some 70' high. Traditionally

the castle is dated to the reign of King Henry I (1100-35) on the

spurious grounds that it looks somewhat like Falaise castle keep in Normandy and the 'fact'

that this reign is when other vaguely similar English keeps ‘must' have been

built. To be safe it is best to date the keep as extant when it

came into the hands of King Henry II (1154-89). When exactly it

was built before that date is currently uncertain, although there are

architectural features in both castle and cathedral that are similar.

However, similarity does not equate to simultaneous construction.

Peckforton castle in Cheshire vaguely mimics nearby Beeston castle, yet

one is Victorian and the other thirteenth century and no one has yet drawn

the erroneous conclusion that because of their similarity both must

date to the same era.

The keep was apparently a free-standing building, so it could have been

built from the first with a palisade surrounding the mound top forming

the main defence while this was constructed. The tower exterior

is decorated with Romanesque blind arcading, which is only found in

military structures in such quality and quantity elsewhere at Castle Rising, although St Leonard's Tower, West Malling, Kent (which probably began

life as a church tower), also displays some blind arcading, as does the

interior of Chepstow keep. Internally, Norwich keep has been

gutted so that nothing certain remains of its medieval layout, although

it is generally agreed that it contained a kitchen, the chapel of St

Nicholas, an entrance hall, a 2 storey hall and a grand total of 16

early garderobes.

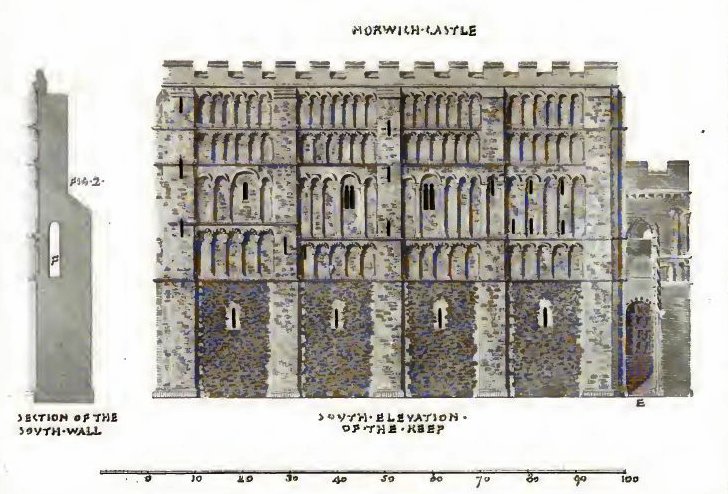

All the apertures in the keep have Romanesque arches which again points

to the tower's early construction date. The ground floor was

apparently flint faced, while the upper storeys were originally thought

to have been of Caen stone. More recently it has been considered

that the bulk of the ashlar consists of Bath stone laid over a flint

core, although some elements are still thought to be of Caen stone. The

lower flintwork presents a stark contrast to the pale limestone of the

upper portion of the keep. Possibly the lower sections would not

have been viewable from the city as the defensive curtain around the

mound perimeter would have shielded it from view. It was

therefore simply plastered to cover the crudity of the walls while the

upper storey was well decorated to impress the locals viewing it from

afar.

All the apertures in the keep have Romanesque arches which again points

to the tower's early construction date. The ground floor was

apparently flint faced, while the upper storeys were originally thought

to have been of Caen stone. More recently it has been considered

that the bulk of the ashlar consists of Bath stone laid over a flint

core, although some elements are still thought to be of Caen stone. The

lower flintwork presents a stark contrast to the pale limestone of the

upper portion of the keep. Possibly the lower sections would not

have been viewable from the city as the defensive curtain around the

mound perimeter would have shielded it from view. It was

therefore simply plastered to cover the crudity of the walls while the

upper storey was well decorated to impress the locals viewing it from

afar.

The keep basement contained the great hall and above this

were private rooms and the upper floor. The basement was

bisected into

2 by a crosswall. The northern room had a row of square piers in

the centre supporting a stone vault, while the southern room had two

vaulted compartments at its east end. Norwich castle, like many

other administrative centres, had been used as a jail since the twelfth

century at the latest. The new attached jail was built by Sir

John Soane during 1789-93.

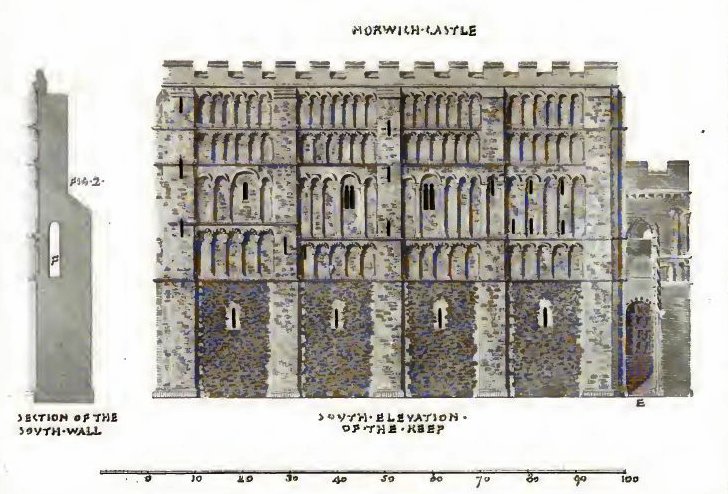

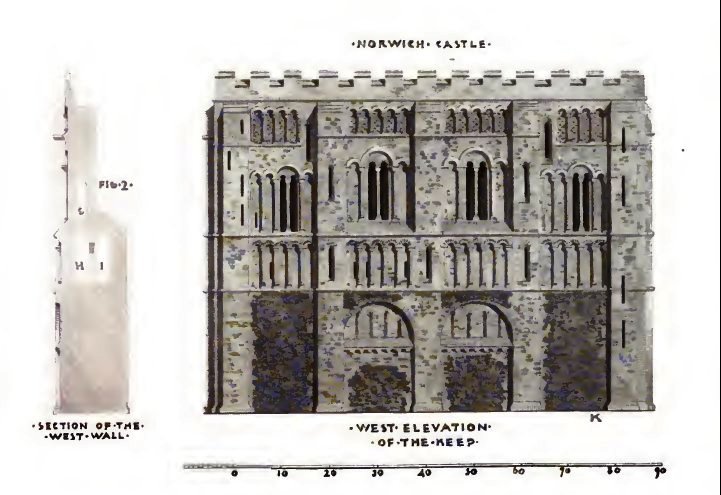

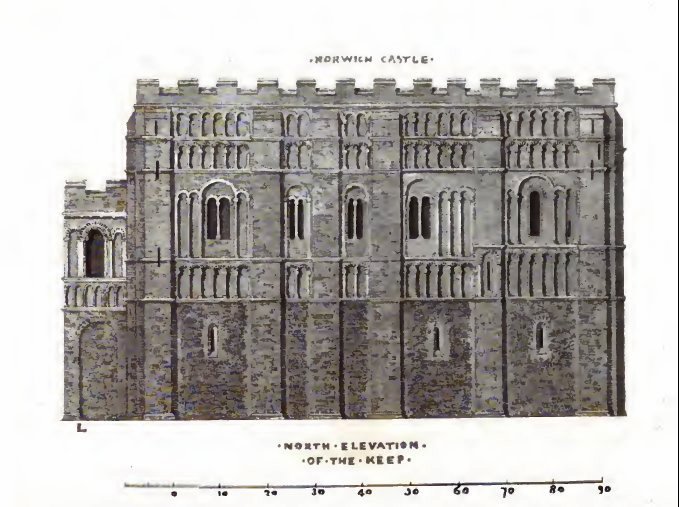

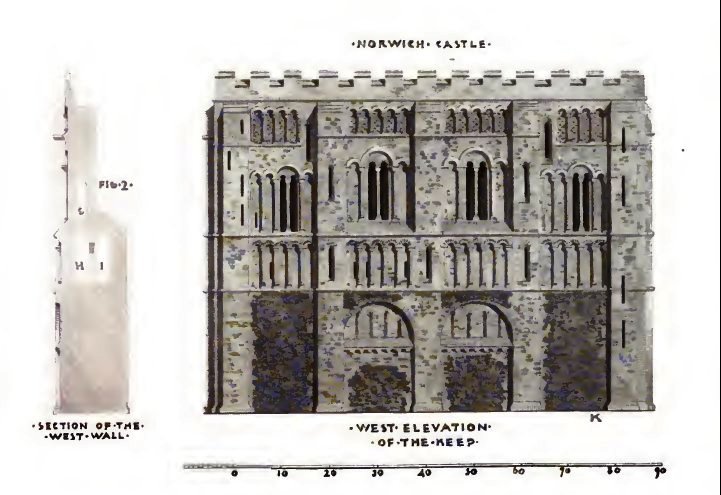

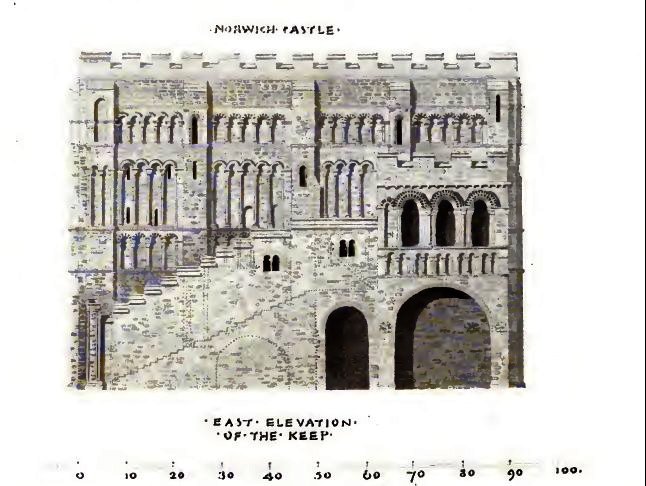

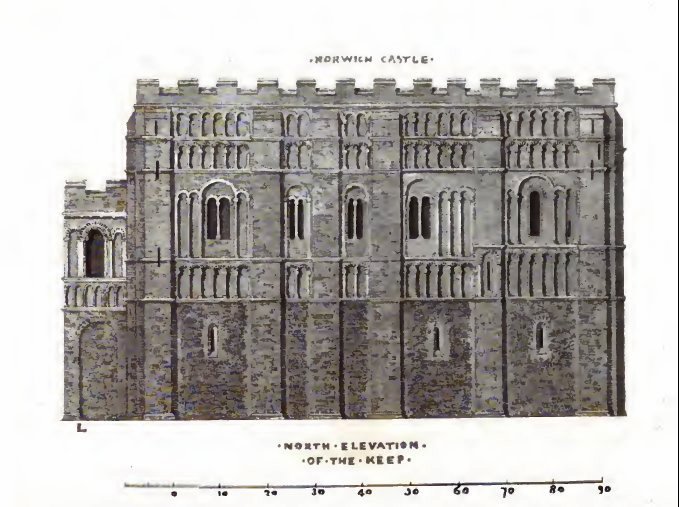

The exterior faces of the keep are divided into 4 bays by wide pilaster

buttresses with decorative nicked buttresses at the corners - and for

some reason the north front has an extra buttress added to divide the

second bay from the east. The ground floor is decorated by 3 or 4

tiers of blind arcading differing in height and width. These

irregularly contain windows, while the 4 latrines, servicing both upper

floor chambers, exit via chutes set in polychrome (brown and white) Romanesque arches in the west

wall. The summit is topped by battlements supported by a

modillion course and has nine pierced and capped merlons on each

side. These are modern and eighteenth century sketches show that

the loops are modern fanciful additions. There are subtle

differences in the decoration on each face but only the south and west

faces are now completely visible. Attached to the east side of

the keep is the modern gatehouse as part of the modern enceinte of the

bailey which surmounts the ‘motte' behind a substantial modern berm.

The exterior faces of the keep are divided into 4 bays by wide pilaster

buttresses with decorative nicked buttresses at the corners - and for

some reason the north front has an extra buttress added to divide the

second bay from the east. The ground floor is decorated by 3 or 4

tiers of blind arcading differing in height and width. These

irregularly contain windows, while the 4 latrines, servicing both upper

floor chambers, exit via chutes set in polychrome (brown and white) Romanesque arches in the west

wall. The summit is topped by battlements supported by a

modillion course and has nine pierced and capped merlons on each

side. These are modern and eighteenth century sketches show that

the loops are modern fanciful additions. There are subtle

differences in the decoration on each face but only the south and west

faces are now completely visible. Attached to the east side of

the keep is the modern gatehouse as part of the modern enceinte of the

bailey which surmounts the ‘motte' behind a substantial modern berm.

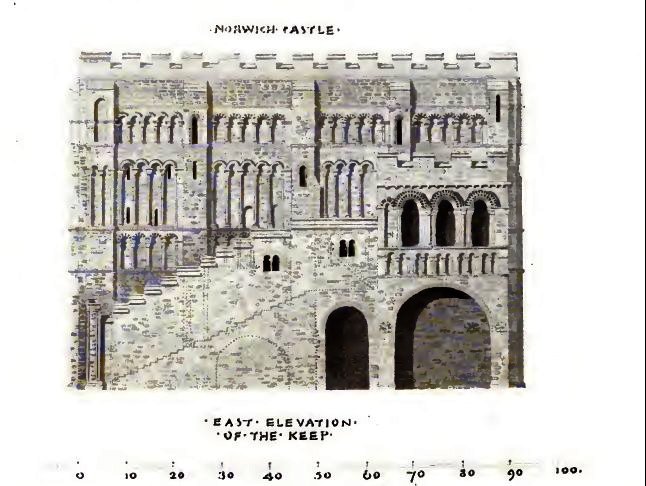

The

keep was entered on the upper floor from a 2 storey forebuilding

called the Bigod tower which lay on the east side. This was

reached by an external stone staircase running along the face of the

wall. Sir John Soane, during his renovations of the keep in

1789-93, oversaw the rebuilding of the Bigod tower even though he would

have preferred it to be demolished. Despite his attentions the

vault of the tower still survives under the current structure, although

the Romanesque arches on which the staircase rose has been destroyed

together with the carved lions on the imposts.

The vault has a quadripartite rib-vault, with roll moulded ribs.

It is

probable that the whole of the eastern side of the keep was also

refaced when the Bigod tower was rebuilt. In appearance this

forebuilding seems to have something in common with that at Castle

Rising.

The

keep was entered on the upper floor from a 2 storey forebuilding

called the Bigod tower which lay on the east side. This was

reached by an external stone staircase running along the face of the

wall. Sir John Soane, during his renovations of the keep in

1789-93, oversaw the rebuilding of the Bigod tower even though he would

have preferred it to be demolished. Despite his attentions the

vault of the tower still survives under the current structure, although

the Romanesque arches on which the staircase rose has been destroyed

together with the carved lions on the imposts.

The vault has a quadripartite rib-vault, with roll moulded ribs.

It is

probable that the whole of the eastern side of the keep was also

refaced when the Bigod tower was rebuilt. In appearance this

forebuilding seems to have something in common with that at Castle

Rising.

The Norwich keep upper floor consisted of a great chamber to the south

and a great hall to the north, with a external entrance into the east

end of the hall. This Romanesque entrance is the most ornate

piece of Norman carving in the keep, having three orders of shafts some

with a beakhead motif. The arches have a roll moulding with

panels in between carrying interlace, foliage and little animals.

On the capitals are carved figures and animals from hunting

scenes. The whole portal is surrounded by a wider arch decorated

with large four-petal flowers, while beside it is a much smaller blind

arch. Possibly this was intended to mimic the large and small

gateways often found in Roman cities. This style lived on longer

in France where most gatehouses contained a foot and a horse passage

into the castle. This style can still be seen at the early

gatehouse at Ludlow in Shropshire and in the fifteenth century keep at

Raglan, but the latter quite obviously copies the common late medieval form

in France, viz. Bricquebec, Fougeres, Langeias, Loches city walls and

Tonquedec to name a few.

The Norwich keep upper floor consisted of a great chamber to the south

and a great hall to the north, with a external entrance into the east

end of the hall. This Romanesque entrance is the most ornate

piece of Norman carving in the keep, having three orders of shafts some

with a beakhead motif. The arches have a roll moulding with

panels in between carrying interlace, foliage and little animals.

On the capitals are carved figures and animals from hunting

scenes. The whole portal is surrounded by a wider arch decorated

with large four-petal flowers, while beside it is a much smaller blind

arch. Possibly this was intended to mimic the large and small

gateways often found in Roman cities. This style lived on longer

in France where most gatehouses contained a foot and a horse passage

into the castle. This style can still be seen at the early

gatehouse at Ludlow in Shropshire and in the fifteenth century keep at

Raglan, but the latter quite obviously copies the common late medieval form

in France, viz. Bricquebec, Fougeres, Langeias, Loches city walls and

Tonquedec to name a few.

The upper floor great chamber had a number of subsidiary rooms,

including a chapel in the south-east corner of the keep and a private

chamber to the south-west. The room had a fireplace in the south

wall and a well near the crosswall which is not quite the same design

as Rochester which had the well set within the crosswall. Despite

its early date, both halls were served by two sets of garderobe chutes

in the west wall. It also had wall passages along each

side. It has been suggested that there was an ‘appearance

doorway' on the west side of the keep where the constable or king could

make himself known to the city lying in that direction.

From the Norwich great hall, which contained a fireplace, stairs led

downwards in both the north-west and north-east corners. Only the

ground floor of the west wall of the keep has no apertures, but at the

north end evidence of vaulting can be seen in the wall. This

supported the stone-flagged floor of the kitchen immediately above in

the Great Hall. Within the kitchen is a fireplace in the

north-west corner.

By the end of the eighteenth century the keep was showing signs of

collapse and so was entirely refaced in 1835-8 by Anthony Salvin, who

had already worked on Rockingham, the Tower of London, Warwick and

Windsor castles. At Norwich he continued the work begun by

Francis Stone around 1829 and who had died in 1835. Stone's work

consisted of the east face and Salvin was employed to refashion the

remaining sides in a similar manner. This is thought to have been

very close to the original.

In 1887 the castle was converted into a museum. This resulted in

the gutting of the castle's interior and the creation of top-lit

galleries in the former cell blocks. The new keep roof was

supported by an arcade in the position of the former crosswall and a

gallery was installed at the level of the original floor of the upper

halls.

The Baileys

From documentary sources, it is known that the castle had a southern

bailey with an inner barbican, a kidney shaped bailey on the north-east

side, while the whole area was bounded by a probably ditch and bank

which made up the area called Castle Fees.

Since the fourteenth century encroachment and infilling have levelled

the ditch to the north and west of the main castle mound. The

ditch is now occupied by the modern road, Castle Meadow to the north

and west. East of the mound Market Avenue appears to follow the

edge of the outer bank of the infilled moat in which has been built the

Victorian shire hall. The built up area to the east of this,

where the land falls away gradually, formed a part of the defended

meadow that was the north-east bailey. The baileys to the south

of the castle mound ditch were substantially removed by excavation and

then built upon by the Castle Mall shopping centre, totally destroying

their original form.

Just south-west of the ‘motte' bridge was a substantial early

medieval well some 100' deep, the bottom 2 thirds of which was cut

through the natural chalk. Excavation has shown that there were

only a small number of buildings in the southern bailey and that some

of these may have continued in use from the Saxon era. South of

the ‘motte' bridge was what appeared to be a rectangular

gatetower which had later collapsed into the later barbican ditch to

the south. The gatetower's walls were about 6' thick and it was

thought the tower was brought down by sand quarrying in the post

medieval period.

South of the probable gatetower lay the deep barbican ditch. Some

60% of this has been archaeologically investigated before its

destruction. This created a quarter moon barbican which is

somewhat similar to other examples that are generally reckoned to be

early thirteenth century, viz. Dunamase in Ireland as well as that at

Castle Rising. Beyond the

barbican ditch a series of 2

semi-circular ditches were dug to further protect the entrance to the

purported gatehouse. These have been interpreted as part of a

hornwork. It is noticeable that nowhere in records of the

surviving remains, which includes the keep entrance, 2 gates in the

forebuilding, the 2 gates at the bridge or the south gatetower, could

any trace of a portcullis be found.

The bailey to the north-east has largely been unexamined

archaeologically, although small investigations have suggested that the

ward was largely devoid of buildings, before it was encroached upon by

the city. Recorded as the Castle Meadow from 1351-52, it may well

have been a bailey from the first building of the castle.

The Medieval City

Construction of the city walls seems to have taken place between 1253

and 1344 and covered an area measuring one and a half miles from north

to south and one mile from east to west. No trace of any burgh

defence remains and it is possible that the burgh was always at Caistor

St Edmunds, 3 miles to the south. Surprisingly the thirteenth

century defensive area of Norwich city was greater than that covered by

the contemporary London walls, while the buildings within the walls

included the Benedictine monastery and cathedral, 4 large friary

precincts, nearly 70 churches, several hospitals, a thriving commercial

waterfront and numerous markets.

The castle lies roughly centrally within the surviving circuit, while

large sections of masonry remain visible along the A147 including

several D shaped mural towers. This section of wall cut off the

city from riverside to riverside along the south and west fronts.

The east side was covered solely by the river Wensum, although to the

north there was a large suburb known as Norwich over the water.

This ran from the fine fourteenth century brick artillery Cow Tower on

the south side of the river to some distance north of the main walls on

the River Wensum.

Copyright©2021

Paul Martin Remfry

The Keep

The Keep All the apertures in the keep have Romanesque arches which again points

to the tower's early construction date. The ground floor was

apparently flint faced, while the upper storeys were originally thought

to have been of Caen stone. More recently it has been considered

that the bulk of the ashlar consists of Bath stone laid over a flint

core, although some elements are still thought to be of Caen stone. The

lower flintwork presents a stark contrast to the pale limestone of the

upper portion of the keep. Possibly the lower sections would not

have been viewable from the city as the defensive curtain around the

mound perimeter would have shielded it from view. It was

therefore simply plastered to cover the crudity of the walls while the

upper storey was well decorated to impress the locals viewing it from

afar.

All the apertures in the keep have Romanesque arches which again points

to the tower's early construction date. The ground floor was

apparently flint faced, while the upper storeys were originally thought

to have been of Caen stone. More recently it has been considered

that the bulk of the ashlar consists of Bath stone laid over a flint

core, although some elements are still thought to be of Caen stone. The

lower flintwork presents a stark contrast to the pale limestone of the

upper portion of the keep. Possibly the lower sections would not

have been viewable from the city as the defensive curtain around the

mound perimeter would have shielded it from view. It was

therefore simply plastered to cover the crudity of the walls while the

upper storey was well decorated to impress the locals viewing it from

afar. The exterior faces of the keep are divided into 4 bays by wide pilaster

buttresses with decorative nicked buttresses at the corners - and for

some reason the north front has an extra buttress added to divide the

second bay from the east. The ground floor is decorated by 3 or 4

tiers of blind arcading differing in height and width. These

irregularly contain windows, while the 4 latrines, servicing both upper

floor chambers, exit via chutes set in polychrome (brown and white) Romanesque arches in the west

wall. The summit is topped by battlements supported by a

modillion course and has nine pierced and capped merlons on each

side. These are modern and eighteenth century sketches show that

the loops are modern fanciful additions. There are subtle

differences in the decoration on each face but only the south and west

faces are now completely visible. Attached to the east side of

the keep is the modern gatehouse as part of the modern enceinte of the

bailey which surmounts the ‘motte' behind a substantial modern berm.

The exterior faces of the keep are divided into 4 bays by wide pilaster

buttresses with decorative nicked buttresses at the corners - and for

some reason the north front has an extra buttress added to divide the

second bay from the east. The ground floor is decorated by 3 or 4

tiers of blind arcading differing in height and width. These

irregularly contain windows, while the 4 latrines, servicing both upper

floor chambers, exit via chutes set in polychrome (brown and white) Romanesque arches in the west

wall. The summit is topped by battlements supported by a

modillion course and has nine pierced and capped merlons on each

side. These are modern and eighteenth century sketches show that

the loops are modern fanciful additions. There are subtle

differences in the decoration on each face but only the south and west

faces are now completely visible. Attached to the east side of

the keep is the modern gatehouse as part of the modern enceinte of the

bailey which surmounts the ‘motte' behind a substantial modern berm. The

keep was entered on the upper floor from a 2 storey forebuilding

called the Bigod tower which lay on the east side. This was

reached by an external stone staircase running along the face of the

wall. Sir John Soane, during his renovations of the keep in

1789-93, oversaw the rebuilding of the Bigod tower even though he would

have preferred it to be demolished. Despite his attentions the

vault of the tower still survives under the current structure, although

the Romanesque arches on which the staircase rose has been destroyed

together with the carved lions on the imposts.

The vault has a quadripartite rib-vault, with roll moulded ribs.

It is

probable that the whole of the eastern side of the keep was also

refaced when the Bigod tower was rebuilt. In appearance this

forebuilding seems to have something in common with that at Castle

Rising.

The

keep was entered on the upper floor from a 2 storey forebuilding

called the Bigod tower which lay on the east side. This was

reached by an external stone staircase running along the face of the

wall. Sir John Soane, during his renovations of the keep in

1789-93, oversaw the rebuilding of the Bigod tower even though he would

have preferred it to be demolished. Despite his attentions the

vault of the tower still survives under the current structure, although

the Romanesque arches on which the staircase rose has been destroyed

together with the carved lions on the imposts.

The vault has a quadripartite rib-vault, with roll moulded ribs.

It is

probable that the whole of the eastern side of the keep was also

refaced when the Bigod tower was rebuilt. In appearance this

forebuilding seems to have something in common with that at Castle

Rising. The Norwich keep upper floor consisted of a great chamber to the south

and a great hall to the north, with a external entrance into the east

end of the hall. This Romanesque entrance is the most ornate

piece of Norman carving in the keep, having three orders of shafts some

with a beakhead motif. The arches have a roll moulding with

panels in between carrying interlace, foliage and little animals.

On the capitals are carved figures and animals from hunting

scenes. The whole portal is surrounded by a wider arch decorated

with large four-petal flowers, while beside it is a much smaller blind

arch. Possibly this was intended to mimic the large and small

gateways often found in Roman cities. This style lived on longer

in France where most gatehouses contained a foot and a horse passage

into the castle. This style can still be seen at the early

gatehouse at Ludlow in Shropshire and in the fifteenth century keep at

Raglan, but the latter quite obviously copies the common late medieval form

in France, viz. Bricquebec, Fougeres, Langeias, Loches city walls and

Tonquedec to name a few.

The Norwich keep upper floor consisted of a great chamber to the south

and a great hall to the north, with a external entrance into the east

end of the hall. This Romanesque entrance is the most ornate

piece of Norman carving in the keep, having three orders of shafts some

with a beakhead motif. The arches have a roll moulding with

panels in between carrying interlace, foliage and little animals.

On the capitals are carved figures and animals from hunting

scenes. The whole portal is surrounded by a wider arch decorated

with large four-petal flowers, while beside it is a much smaller blind

arch. Possibly this was intended to mimic the large and small

gateways often found in Roman cities. This style lived on longer

in France where most gatehouses contained a foot and a horse passage

into the castle. This style can still be seen at the early

gatehouse at Ludlow in Shropshire and in the fifteenth century keep at

Raglan, but the latter quite obviously copies the common late medieval form

in France, viz. Bricquebec, Fougeres, Langeias, Loches city walls and

Tonquedec to name a few.