Warkworth

Warkworth first enters history in about 737AD when Werceworde was recorded as a land of King Ceolwulf which he held when a monk at Lindisfarne. King Henry II

(1154-89) later confirmed Tynemouth priory's lands. These

included the gifts of Earl Roger of Northumberland (1080-95) amongst

which were the tithes of Corbridge, Newburn, Warkworth (Werchewrth)

and Rothbury. These would all later be held by the lords of

Warkworth. Warkworth is next mentioned in 1165 when it was noted

that Roger Fitz Richard (d.1178) had been given land worth £20 in

the borough of Newcastle and £32 2s in Wercheswrda.

Although the castle is described as a ‘well-documented example of

a twelfth century tower keep castle' the above and what follows shows

that this is not true and the origins, buildings and even if the castle

was of a tower keep design is far from certain.

The foundation of Warkworth castle is undoubtedly entwined in the

Norman annexation of Northumberland which occurred increasingly after

1070. It would therefore be logical to fortify Warkworth, as the

major crossing point of the River Coquet half way between Bamburgh and Newcastle, at any time after Newcastle was founded in 1080. As the land was royal land when reclaimed by Henry II in 1157, it would seem likely that the fortress was a royal construction. The least likely builders would be Henry I (1100-35), King Stephen when he held Northumberland between 1135 and 1139, or Henry II

between 1157 and 1165 by which time he had given it away. It

therefore seems most likely that the motte and bailey castle was built

either between 1139 and 1152 by Earl Henry (d.1152), the lord of Northumberland during that period, or by William Rufus (1087-1100). It is most unlikely that Earl Henry's son, the later King William I of Scotland

(1165-1214), would have built the fortress as he was only the nominal

lord of Northumberland from 1152 until 1157 by which time he had just

reached the age of 14. With the choice between Earl Henry (1139-52), who is known to have built no mottes and William Rufus

(1087-1100), the logical choice would be King William as the

builder. Certainly he may have wanted a castle commanding the

route from Newcastle to Bamburgh during his campaign of 1095.

King William II (1087-1100) is

recorded in only one contemporary source, Florence Worcester, as

having built ‘a siege castle' called Bad Neighbour during the

campaign against Robert Mowbray. Later twelfth and thirteenth

century chronicles elaborated on this story, but with how much

knowledge is unknown. The sources are examined under Bamburgh castle,

but the implication ‘might be' that the siege castle was actually

the foundation of Warkworth castle. Certainly the scale of the

earthworks suggest a royal castle. Further, there is no evidence

that Earl Henry (d.1152) ever built a motte, let alone one on the scale of Warkworth.

Whatever the case of Warkworth's founding, the district including the castles of Norham, Wark, Alnwick, Newcastle, Harbottle and Bamburgh were much fought over in the period following the death of Henry I in 1135 and the establishment of King David of Scotland in Northumberland and Cumberland by the treaty of Durham in 1139. At this point Earl Henry (d.1152) was supposed to become earl of Northumberland in exchange for returning the castles of Bamburgh and Newcastle to King Stephen. However, he seems to have retained both these castles until his death in 1152, while Harbottle, Norham and Wark

were certainly destroyed in 1138 and apparently not rebuilt until the

late 1150s. It is quite possible that Warkworth was similarly

overthrown in this period 1136-39. Consequently it seems unlikely

that Earl Henry would have been troubled to build Warkworth castle if

it didn't exist at this time when Harbottle, Wark and Norham were certainly destroyed. Alnwick,

as the fortress of Eustace Fitz John, not the king, was also allowed to

survive. In 1157 all the surviving fortresses of Northumberland

and the sites of the others were returned to King Henry II (1154-89) who ordered Norham and Wark rebuilt as well as possibly Harbottle. No fortress was mentioned at Warkworth at this time, although Roger Fitz Richard witnessed a royal charter at Newcastle upon Tyne

during the early months of 1158. Possibly he already held the

castle or castle site. Certainly the castle existed by 1164 as

King Henry's brother, William (d.1164), witnessed the king's grant to

Roger Fitz Richard of the castle and manor of Warkworth with all

purtenances just as King Henry I (1100-35) had granted the manor. This charter was recorded in the Quo Warranto

proceedings of the 1290s. The question is, was the castle granted

by Henry I or not, as the late thirteenth century copy clearly states

that Henry I only granted the manor, while Henry II (1154-89) granted

the castle and manor. It also seems unlikely that Henry I could

have granted Warkworth to Roger Fitz Richard if his provenance is

correctly assessed below of him being of the house of Clare. It

is therefore possible that Henry II confirmed Warkworth to Roger on the

strength of a verbal assurance that Henry I had granted the place to

Roger or his predecessor. Certainly no original charter of the

transaction has survived.

Warkworth is mentioned contemporaneously for the first time in 1165

when it was noted that Roger Fitz Richard (d.1179+) had been given land

worth £20 in the borough of Newcastle and £32 2s in Wercheswrda. Roger Fitz Richard was a baron of some weight at the start of the reign of Henry II

(1154-89). At the end of August 1153 Roger was the second of the

3 recorded lords helping Duke Henry of Normandy (d.1189) in the siege

of Stamford castle.

The other 2 were Hugh Beauchamp (d.1187) and Hamon Falaise. Two

months previously Roger had been at Coventry when Duke Henry was

attended by Earl Roger of Hereford (d.1155), Walcheline Maminot (d.1190, of Dover), Warin Fitz Gerold the chamberlain (d.1159), Hugh Piraris (d.1166+, of Corfham)

and Roger Fitz Richard. His good service was obviously rewarded

for in 1156 he was recorded as having been given 7s 7d worth of land in

Suffolk, pardoned 10s Danegeld and 7s 1d gift in Essex, 40s Danegeld

and 50s 8d gift in Warwickshire. In 1158 he was pardoned 35s gift

in Essex as well as being given £58 worth of land in

Northumberland and receiving a gift of 40m (£26 13s 4d) from the

king in the same county. He was also pardoned giving a gift of

62s to the king in Warwickshire. In 1159 he was gifted £52

12s in Northumberland and the next year, 1160, he was given land to the

value of £20 in the borough of Newcastle

and Warkworth worth £32 12s. Quite obviously the land worth

£32 12s included the site of Warkworth castle if the fortress was

not still functional. These payments continued until around

Christmas 1177, although the payments for Newcastle had ceased in

1176. There is no direct evidence as to the provenance of Roger

Fitz Richard, but it should be noted that he was important enough to

marry into the Vere family when he married Alice (d.1185+), the widow

of Robert Essex (d.bef.1140) of Clavering. To this end, and the

fact that the family used Fitz like the Fitz Walters of Dunmow, it is

possible that Roger Fitz Richard was a member of the Clare

family of Essex. The most likely origin of Roger was that he was

a son of Richard Fitz Baldwin who died in 1136, quite possibly

defending his uncle, Richard Clare, who was ambushed and killed at the

start of the Great Welsh Revolt on 15 April 1136.

Whatever his origins, in 1168 Roger Fitz Richard was assigned to view the works going on at Newcastle

at a cost of 47s 4d and further work paid for from Lancashire which

cost £18 18s 8d. In the latter view he was associated with

Robert Stuteville (d.1186). At this time the value of his lands

in Northumberland were valued at 1m (13s 4d) tax for the 1 knight's fee

he held in the county. Presumably this was Warkworth. Roger

paid scutage for 1 fee in Yorkshire in 1172 as he did not participate

in the Irish campaign of that year. During the Young King's war

Roger supported Henry II

(1154-89) and was sent £30 for retaining his knights at Newcastle

by the writ of Richard Lucy. According to the chronicler

Fantosme, during the summer of 1173 King William of Scotland invaded Northumberland and besieged Wark castle, forcing its commander, Roger Stuteville (d.1185+), to request a 40 day truce and send to Henry II (1154-89) for instructions. The Scottish host then went to Alnwick

and called on the young bastard William Vescy (d.1206) to surrender or

make a truce like Wark. This was refused and the king then

marched on nearby Warkworth.

They came to Warkworth, not bothering to stop;

Because the castle was weak, the wall and the earthworks.

And Roger Fitz Richard, a valiant knight,

Had had it in custody; but he was not able to keep it.

Instead Roger waited for the Scottish host within the much more powerful Newcastle.

The implication is that there was no effort made to defend the

castle. That the castle was not mentioned in the subsequent

attack on the borough the next year would suggest it was destroyed in

the summer of 1173.

After taking the undefended Warkworth castle, King William again baulked at an open assault, this time at Newcastle against one of the major fortresses in the North defended by Roger Fitz Richard in person. Instead King William set off for Carlisle via Prudhoe,

both of which he hoped might be easier prey. Therefore the

Scottish attack of 1173 proved largely unsuccessful and King William

was soon forced back over the border by Richard Lucy (d.1179).

However this was not the end of the affair and the Scots invaded again

the next year.

A contemporary source stated that the new campaign of 1174 began with King William of Scotland sending his brother Earl David of Huntingdon (d.1219) to Leicester, to lead the men there against King Henry II (d.1189). William then went with his army to besiege Carlisle

where he tarried a few days, leaving part of his army around the

castle. He soon went in person with the rest of his host to

Northumberland, laying waste the lands of the king and his barons, on

route taking Liddel castle as well as Appleby and Brough,

the latter 2 being royal castles which Robert Stuteville (d.1186) was

keeping. Next they moved against Warkworth castle, which Roger

Fitz Richard held in custody. Finally the Scots took Harbottle castle

which was held by Odinel Umfraville. It is interesting to note

the taking of Warkworth castle is therefore placed in 1174 here.

Yet when the chronicler talks about the attack on Warkworth in detail

no castle is mentioned.

But Earl Duncan at once

divided the army into 3 parts; one part he kept with him and the

remaining 2 he sent to burn the surrounding towns and to slay folk from

the greatest to the least, as well as to carry off spoil. And he

himself with the part of the army which he had chosen entered the town

of Warkworth and burned it, and slew in it all whom he found there, men

and women, great and small; and he made his followers break into the

church of Saint Laurence which was there and slay in it and in the

house of the priest of that town more than a hundred men, besides women

and children; oh, the sorrow! Then you might hear the screaming

of women; the crying of old men; the groans of the dying; the despair

of the young!

Quite clearly the chronicler blundered in his summary which mentions an

attack on the castle in 1174. Fantosme confirms this

scenario. After the attack on Warkworth castle the previous

summer, the early summer of 1174 saw King William back in the North of England besieging Prudhoe for 3 days without result, other than losing good men. He therefore withdrew to besiege Alnwick castle

and on route part of his army violated St Laurence's church in

Warkworth, castrating 3 of the priests there and killing some 300 men,

presumably on route rather than in the church itself. The lack of

mention of the castle probably means that it had not survived the

attentions of the Scottish host in 1173 and that Hoveden compressed the

attack on the castle in 1173 and the attack on the town in 1174 into

one event. In reality the castle seems to have fallen 1173 with

the townsfolk being massacred the next year. Alternatively both

may be right and the castle was sacked on both occasions.

Regardless, after the attack of Warkworth borough in 1174, Roger Fitz

Richard (d.1179+) joined his forces to those of Odinel Umfraville

(d.1182. Prudhoe), Bernard Balliol (d.1190, Barnard Castle) and their

companions and marched on Alnwick where they surprised and captured King William on 13 July 1174. Despite this victory, Roger fell out of favour with Henry II

(1154-89) and was fined 40m (£26 13s 4d) for misdeeds in the

forest of Essex in 1177. Further, his Norfolk and Suffolk manor

of ‘Stanham' was seized by the Crown during the early summer of

1179. It would therefore seem that Roger was stripped of

Warkworth for some failure at the same time. Possibly this was

allowing it to fall to the Scots in 1173/74. King Henry did not

take kindly to other barons who had abandoned their charges without

resistence during that war, viz. Appleby.

Roger Fitz Richard was still alive in 1178 when he fined 20m (£13

6s 8d) for his misdeeds in the Essex forest of which he paid 10m

(£6 13s 4d), the rest being required under Norfolk. He was

last heard of the next year when he and his son, William, paid the last

10m (£6 13s 4d) of his fine in Norfolk. Roger's

Northumberland lands, however, appear to have been in royal hands,

probably since 1174. Roger in 1179 would have been over 44 years

old and left his wife, described as a 60 or 80 year old widow by 1185

when she had 2 recorded sons who were knights. Presumably this

was Roger's heir, Robert Fitz Roger (d.1214) and William Fitz

Roger. There was also a daughter, Alice, who had been born before

1155 and who was by 1185 married to John Fitz Richard (d.1190), a

grandson of Eustace Fitz John of Alnwick (d.1157).

In 1187 the royal borough of Warkworth and its appurtenances of Acklington, High Buston (Werbuttesdun)

and Birling, were taxed £6 6s 8d of which the final 63s 4d was

paid the next year. That these monies were collected by the

sheriff shows that Warkworth was under royal control, even though the

sons of Roger Fitz Richard (d.1179+) were of age by 1185, if not much

earlier. A tallage of 63s 4d was also given from the same places

as a gift to Richard I in

1189. There appears to have been another family of similar names

to the dispossessed lords of Warkworth around at this time with a Roger

Fitz Robert appearing in Dorset in 1188 and a William Fitz Roger,

clerk, and his brother Ralph appearing in Hocton and Hawthorpe (Horthorp)

in Lincolnshire as well as in Suffolk, Essex and Warwickshire with

Leicestershire. Whenever Roger Fitz Robert did die towards the

end of the reign of Henry II

(1154-89), he was eventually succeeded by his son, Robert Fitz Roger

(d.1214). He does not seem to have been the man mentioned from

1185 to 1187 in Nottingham and Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, the honour of

Bristol and Warwickshire and Leicestershire. This man seems to

have ended his days as an outlaw. The Robert of Warkworth had

witnessed his father's foundation of Aynho hospital in 1170 and

appeared as a knight in 1185. This suggests that he had been born

before 1164.

The affairs of Robert Fitz Roger (d.1214) improved immeasurably for the better when Richard I took the throne in 1189. Around the time of the death of King Henry II

(6 July 1189) Robert was granted Blythburgh in Suffolk. This

property was previously held by Hugh Cressy (d.1189), the deceased

first husband of Robert's wife, Margaret Caisneto (d.1230). It

consisted of some 11 fees in East Anglia. A year later in the

Spring of 1190, it was also recorded that the sheriff of Northumberland

was allowed £16 12d in his account as Werkewurda

with purtenances were now no longer a part of the royal demesne from

that time forward by royal charter. However, it was noted that a

gift of 60s 4d had been raised on the borough and its purtenances,

presumably before this grant was made. Therefore it seems

that Warkworth was under royal control from to 1174/79 to 1190.

On 5 April 1194 King William of Scots petitioned King Richard to restore the counties of Northumberland, Cumberland,

Westmorland and Lancashire to him to hold as his ancestors had held

them. The king deferred his answer until he could take the

opinion of his council. On 8 April Richard was attended by

William St Mere Eglise (d.1224), Robert Fitz Roger, Robert Tregoz

(d.1214) and Guy Dive at Northampton. Presumably Robert was part

of this council and on 11 April the king refused the petition of the

Scottish king. Then on 16 April 1194, the king granted Robert the

manor of Iver (Eura)

in Buckinghamshire. Those laymen with the king at this time

included Earl David of Huntingdon (d.1219), Earl Ranulf of Chester

(d.1232), Earl Roger Bigod (d.1221), Earl William Ferrers (d.1247),

William St Mere Eglise (d.1224)..., William Marshall (d.1219), Geoffrey

Fitz Peter (d.1213), Hugh Bardolf (d.1197), William Warenne (d.1240),

Osbert Fitz Hervey, William Lestrange (d.1203+), Robert Tresgoz

(d.1214) and Philip Fitz Robert. The next day King William took

part in King Richard's second coronation. Robert was still with

the king at Portsmouth during May when he attempted to Cross the

Channel to Normandy and presumably then campaigned with Richard in

Normandy after the crossing was achieved. During September 1194

it was recorded that the grant of Iver in Wallingford lordship had

cost Robert 500m (£333 6s 8d). Around the same time King Richard

granted him 11 fees in Eye lordship. The same year, 1194, Robert

was recorded as owing £9 12s 4d from the farm of Saham in Norfolk

in 1193, but Robert claimed the amount was required from the earl of

Clare. This again could suggest a link between the lords of

Warkworth and the Clares.

Two years later Robert was found with the king in Normandy, this time at the building of Chateau Gaillard.

He would appear to have remained with the king for the bulk of the

royal campaigns against King Philip Augustus of France and was present

at the peace treaty made between them at Les Andelys in June or July

1197. Before 1 September 1197, allegedly in 1195, Robert founded

Langley abbey, Norfolk. Finally in 1197, Robert fined

for 100m (£66 13s 4d) to obtain the marriage of the son and heir

of Hugh Cressy which was granted by the advice of the archbishop of

Canterbury and other relatives of the child.

During the reign of King John

(1199-1216) Robert's career continued apace. In 1199 Robert was

confirmed in his knight's fee in Northumberland, wrongly said to have

been granted him by Henry II in

1168. This was probably Warkworth which was still valued as a

loss to the Crown of £32 2s pa. The same year it was

recorded that Robert had paid 300m (£200) to have his charters

renewed, these being the gift by King Henry and King Richard

by which he held seisin of his lands. This transaction was

carried out under Norfolk and Suffolk, although it is widely stated

that this referred solely to Warkworth. However, it was on 23

July 1200, King John made an important charter to Robert Fitz Roger

where he confirmed to him the gift which King Henry (1154-89) made to Roger Fitz Richard in hereditary fee for his service, namely the castle of Werkewrd and the manor with all its purtenances just as King Henry

(1100-35), Henry's grandfather, had held them. Possibly King

Henry II's charter actually said this as Henry often harked back to the

days of his grandfather in his chancery. The evidence as it stands

strongly implies that Warkworth castle was standing during the reign of

King Henry I (1100-35) and therefore strengthens the impression that William Rufus

was probably responsible for the castle's foundation in 1095.

Certainly I can think of no mottes actually built by Henry I (1100-35).

Around the accession of King John, Robert also briefly acquired the honour of Tickhill in Yorkshire and possibly Aylsham (Aillesham) and Cawston (Causton)

in Norfolk, although these may have belonged to another Robert Fitz

Roger. In 1200 Robert became sheriff of Northumberland until 1202

and the king reset his many debts to 450m (£300) which had to be

paid off at 100m (£66 13s 4d) pa. Before this was even

begun the king forgave him another 200m (£133 6s 8d) .

Robert soon paid what remained of his debt at the correct rate.

Warkworth had 2 mentions when King John confirmed the properties of

Brinkburn priory on 19 February 1201. One of the gifts was a toft

from German Tisun in Werkewurth

as well as a salt works from the same vill by Robert Fitz Roger.

The same year the tithes of Warkworth were also confirmed to Tynemouth priory.

On 13 August 1204, King John

told Robert, no doubt in his capacity as sheriff of Northumberland, to

repair those royal castles he had in custody by the view and testimony

of honest men. This explains Robert spending £33 4s 3d on

castle works at Bamburgh and Newcastle

that Michaelmas. Robert then made the last major addition to his

lands when the king granted him the farm of the manors of Corbridge and

Rothbury on 15 October 1205. Robert remained sheriff of

Northumberland for the rest of his life, although he usually had a

companion working with him.

On his tour of the north King John's scribe wrote 3 letters from

Warkworth on 2 February 1212. Within six months Robert Fitz Roger

was dead, aged at least 50. Consequently, on 12 August 1212, King John gave a charter to John Fitz Robert Fitz Roger confirming the gift by Henry II

(1154-89) to the castle and manor of Warkworth with all purtenances as

that king had given to Roger Fitz Richard the father of Robert and

which King Richard I (1189-99) had confirmed to Robert for the service of 1 knight; also from the gift of the same King Henry the manor of Clavering

with purtenances as was given to Robert and which was confirmed for the

service of 1 knight and the manor of Newburn for 1 knight and the

service of Robert Trukelegna for the service of 40s pa and the manor of

Whalton with all the barony which was Robert Cramaville's for the

service of 3 knights; and the manor of Corbridge at fee for a rent of

£10 for which John returned the charters of King Henry and King

Richard. At September 1214, it was recorded that John held the

following places with their notional value, viz. £32 2s in

Warkworth and purtenances, £30 in Newburn, £30 in

Corbridge, £20 in Rothbury, 40s in Whittingham with the

custody of the heir of William Flamville, in Durham bishopric £23

14s 3d in the wapentake of Seberge [within which stood Barnards Castle] and in the town of Newcastle £50.

John Fitz Robert at some point married into the Balliol family, taking

Ada Balliol (d.1251) as his wife. She brought him Stokesley,

Yorkshire, as her dower. During the Baron's War of 1215-17, John

Fitz Robert was named as one of the surety barons for Magna

Carta. King John appears not to have moved against Fitz Robert

this year, for attacks by the king were recorded around the castles of Alnwick, Mitford, Morpeth and Wark, but not Warkworth. John Fitz Robert appears to have remained initially loyal and was on 1 May 1215 made constable of Norwich castle

for King John. This must soon have been revoked for by 16 March

1216 the king had seized his manor of Aynho. Certainly after the

battle of Lincoln in May 1217, he submitted to the new government of Henry III

(1216-72) on 25 July 1217. Despite this on 8 November 1217, he

was stripped of his farm of Corbridge and ordered to hand it over to

his old colleague, Philip Oldcoats (d.1221). Regardless one John

Fitz Robert was still sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk on 31 October

1217. On 3 February 1221, John of Warkworth was amongst various

northern barons who were ordered to assess and then destroy Skipsea castle due to the rebellion of Earl William Aumale of Cockermouth.

Then, on 19 February 1221, he was ordered to join the full feudal host

of England that was ordered to converge on and destroy Bytham

Castle. Like his father John became sheriff of Northumberland, in

his case from 1224 to 1227. On 16 April 1225 he was ordered, as

sheriff, to repair the king's houses in Newcastle keep, while in August 1224 he had participated in the siege of Bedford castle.

John Fitz Robert died a little before 20 February 1241 when he held

lands in lands in Buckinghamshire Northumberland, Oxfordshire, Norfolk

and Suffolk and was aged over 50. He was succeeded by his young

son Roger who died young a little before 22 June 1249 when his son

Robert was just 1½ years old. At this time he was holding Clavering in Essex for 1 fee of the honour of Raleigh, Datchworth (Thacheworthe)

in Hertfordshire, Aynho in Northampton for 1 fee and Warkworth which

was extended in full. This consisted of a borough and new town, a

mill from which the prior of Tynemouth received 3m (£2) yearly, a

fishery with a small ship called ‘Cobel', a little round wood

called Sunderland and the vills of Acklington, Birling, Buston and a

quarter of Togston out of which were due to Durham church 20s pa

for sustaining 4 wax tapers about the body of St Cuthbert by the deed

of Robert Fitz Roger (d.1179+). Roger was also accustomed to give

yearly for the keeping of the castle and manor £18 6s 8d, 3 robes

and hay and oats for 2 horses. Warkworth church was held by the

bishop of Carlisle. There were also

the vill and forest of Rothbury with the towns of Rothbury, Thropton,

Snitter and Newtown from which 20s was due yearly at the

Exchequer. For the land of Cherland there was a forester with a

horse who had 40s and a robe yearly for his service, while 3 foot

foresters had 60s and their robes. Rothbury church was in the

gift of the bishop of Carlisle by the collation of King Henry I

(1100-35). On 5 May 1241, the king assigned as dower to John's

widow, Ada Balliol, the manors of Newburn and Whalton in Northumberland

and Iver in Buckinghamshire. It should be noted that another John

Fitz Robert survived his namesake and was still lord of half a fee at

Haregworth in Northamptonshire and another half at Pottun in Bedford

and Buckinghamshire on 6 November 1241. Possibly he was the same

man who had been sheriff of Norfolk in 1215.

John's son, Roger Fitz John, died young, at least 20 years old, around

the beginning of June 1249, at a tournament apparently in Argences,

Normandy. He left a 1½ year old son, Robert Fitz Roger

(d.1310) as heir. On 14 August 1249, the king granted the

wardship of two thirds of the lands late of Roger Fitz John to William

Valance (d.1296), the lord of Goodrich castle.

These lands were extended at £145 8s 6½d, except for

£4 8s 10½d which the king granted to him for the keeping

of Warkworth castle on condition that this extend is deducted from

William's yearly fee at the Exchequer. By this act Valance was to

hold the barony until the coming of age of the heirs, or if they died

he would give up the lands and receive the like money back from the

Exchequer as his yearly fee. He was also granted the marriage of

Isabel, the widow of Roger. She also, no doubt, received the

remaining third of the barony as dower, although the king refused the

offer of Ada Balliol (d.1251) to buy the custody of her grandson for

1,200m (£800). Interestingly, at this time Matthew Paris (d.1259) described the castle as noble (nobili castro de Wercwurthe).

On 21 May 1268, William Valance (d.1295) made an agreement with Robert

Fitz Roger whereby he returned the manors of Blythburgh and Blickling,

the land that belonged to Margaret Cressy the daughter of William

Cheynne, with West Lexham (Westlechesham) and Filby (Phileby)

lately held by Stephen Cressy, deceased. Valance, in 1266, had

negotiated to acquire the whole land in the right of Robert Fitz Roger

(d.1310). The same year Robert agreed that he owed William 450m

(£300) to be paid off at 200m (£133 6s 8d) per annum, or

have the sums raised from his lands and chattels in Essex and

Northumberland, but this agreement was immediately cancelled and the

payments quashed. With Robert's coming of age he became much

involved in the wars of the times. He fought in Wales in 1277 and

1282-83, was at the parliament that condemned Dafydd ap Gruffydd

(d.1283) and then was much active in the Scottish wars until his death

in 1310.

In 1292 Warkworth briefly paid host to King Edward I. On 21 November Edward left Norham where Edward Balliol had paid him homage and moved via Wark to Roxburgh on 26 November. He left Roxburgh on 11 December and began a perambulation around Northumberland which saw him staying at Alnwick on 17 December and then Warkworth on the eighteenth. He eventually spent Christmas and New Year at Newcastle upon Tyne

where Edward Balliol again paid homage to him. In 1295, Robert

Fitz Roger (d.1310) was called before the Quo Warranto commission to

see by what right he held the right of wreck on his part of sea coast

in Warkworth liberty, his free forest in Rothbury, his rights in

Corbridge and free warren in Warkworth, Whalton and Newburn and

his markets and fairs. He claimed most of these dated back to

antiquity or the time of King John. On 11 September 1297 Robert

was captured at the battle of Stirling Bridge, but was realised in time

to fight at Falkirk the next year with his son and heir, John Fitz

Robert. He also took part in the siege of Caerlaverock in 1300, the defence of Berwick in 1302 and the battle of Methven in 1306.

Robert Fitz Roger died aged over 62, a little before 29 April 1310,

leaving his son, John Fitz Robert or John Clavering as he was otherwise

known aged over 40. Robert's lands were listed and included, Iver

in Buckinghamshire, Clavering

in Essex, Horsford in Norfolk, Blythburgh in Suffolk and the bulk of

his lands in Northumberland - viz. Whalton, Widdrington, Lynton, Eshott

and Bockenfield, Horton, Ogle (O[ggille?]), South Gosforth, Newham,

Denton, Fawdon, Kenton and Newbiggin on the Moor, Shotton in Glendale,

Herle, Kirkharle, Herle and lands called Cheuervile, Ripplinton,

Newburn with the hamlets of Walbottle, Deuelawe and Botirlawe, Throckelawe, Deuelawe,

Corbridge, Warkworth castle and borough including the new borough with

the hamlets of Birling and Acklington, Upper Botilston, Togston and

Rothbury with the hamlets of Newtown, Thropton and Snitter. The

king granted John his father's lands on his doing homage on 29 May

1310. The barony was obviously in trouble from the first and it

soon becomes apparent that John was continually short of money.

On 20 November 1311, the king granted John land to the value of

£400 a year in Norfolk around the manor of Costessey as well

as lands in Suffolk and Northamptonshire on condition that John willed

his castle of Warkworth with the manors of Rothbury, Newburn, Corbridge

and Iver to the king on his death. In the meantime he and his

wife, Hawise, were allowed to hold them for life. The value of

John's lands was reckoned at £700 in value.

On 8 July 1316, John Clavering received protection for 1 year for his

chattels in his manors of Newburn, Corbridge, Rothbury and Warkworth,

Northumberland, from which nothing was to be taken. It would

therefore appear that he was being pursued for debts. Piracy was

also taking place in the district. On 13 November 1316, a

commission of oyer and terminer was granted concerning a ship laden

with provisions for Berwick on Tweed that

was forced by piratical attacks into Warkworth port where the ship was

boarded by Richard Thirlewal, Robert Arreyns, Eustace le Constable of

Warkworth, John Aketon, Hugh Gulum and John Lescebury and stripped of

its contents. The ship was then impounded. In 1318 the

castle garrison, with those of Bamburgh and Alnwick

combined to seize the 2 ‘piles' of Bolton and Whittingham which

were opposing the king. A little more is learned of the castle

garrison on 28 September 1319, when King Edward II

(1307-27) accounted for an addition to the garrison for the castle of 4

men at arms and 8 hobelars to enhance the existing force of 12 men at

arms.

On 15 September 1322, Earl David of Athol (d.1326) was appointed as

chief warden of Northumberland and its marches and various lords were

ordered to give him aid with their entire posse as he commanded, but

keeping sufficient force to guard their castles. The order was

given to Henry Percy (d.1352) for Alnwick, Ralph Neville (d.1331) for Warkworth, Roger Horsle for Bamburgh, John Lillebourn and Roger Mauduyt for Dunstanburgh, the constable of Prudhoe and Richard Emedlon as chief warden of Newcastle upon Tyne.

At the time Warkworth garrison sent 26 hobelars for the ill fated

Scottish campaign. Ralph Neville (d.1331), the keeper of

Warkworth castle, was married to John Clavering's daughter, Euphemia

(d.bef.1301). He was also lord of Brancepeth castle.

On 2 August 1326, John Clavering was ordered to repair to his castle of

Warkworth as ‘magnates having castles and fortresses in those

parts should stay there for the defence of those parts'. Within 2

months the king complained to Neville that small Scottish forces were

penetrating the district and that he, with the constables of Alnwick, Bamburgh, Dunstanburgh and Norham, were doing nothing to repel them.

On 20 February 1327, it was noted that

John Clavering (d.1332) had granted Edward II

(1307-27) the reversion of Warkworth castle and other lands in

Northumberland on a promise that he should have a suitable marriage for

one of his sisters, but this was not done; therefore in recompense for

the loss of the marriage and his expenses in going to Scotland as

king's messenger he is released of his arrears of the farm of Corbridge

which he holds for a yearly rent of £40 and which is greatly

impoverished and wasted by the frequent attacks of the Scots.

Consequently he is to have that town for life without payment of any

rent. This immediately followed the Scots attacking Norham castle on 1 February. Then on 30 June 1327, Ralph Neville (d.1331) was granted £157 7s 6d out of the customs of Newcastle to discharge the debt for his wages as well as the wages of the men at arms and hobelars who he retained in the service of Edward II when he was constable of Warkworth castle. In August 1327, Robert Bruce's forces are said to

have attacked Warkworth castle after they had unsuccessfully attacked Alnwick.

This is obviously an anachronistic entry as it is stated that Warkworth

belonged to Henry Percy (d.1352). This transfer did not happen

until 1328, which means the chronicler was writing after this

date. Scottish sources only mention attacks on Norham and Alnwick

castles after the July to August Weardale campaign. Then, towards

the end of the year, while Edward III was preparing for his marriage to

Philippa of Hainault, Bruce entered Northumberland again and besieged Alnwick, Warkworth and other castles, although they all held, killing some of Bruce's men.

The next year on 1 March 1328, a royal grant was made to Henry Percy

(d.1352) in fee simple of the reversion of Warkworth castle after the

death of John Clavering (d.1332), tenant for life and in the event of

his death without male issue of all the other lands in the county held

by him in fee tail, provided that the 500m (£333 6s 8d) yearly

now payable to Percy in time of peace or war by indenture, that he

remains with a certain number of men at arms shall cease and also that

he accounts for any excess if the issues of the castle and lands exceed

500m (£333 6s 8d) . This was the same day the treaty of

Northampton, actually ratified on 4 May 1328, was said to begin

from. The treaty recognised that Robert Bruce should possess the kingdom of Scotland without any homage. That his son, David Bruce

(d.1371), should marry Joan Plantagenet (d.1362) and that England and

Scotland should become ‘good allies' and subjects of either

kingdom should not hold any lands in the other. For this Bruce

would pay 30,000m (£20,000) within 3 years and King Edward III

(1327-77) would use his influence to have the pope release Bruce and

his subjects from excommunication and interdict. Both these

latter points were fulfilled. On 13 May 1329, King Edward

consented to receive 5,000m (£3,333 6s 8d) on account of the

10,000m (£6,666 13s 4d) due, the balance to be paid at

Martinmas. After King Robert's

death on 7 June 1329, the king acknowledged receipt of the first 5,000m

(£3,333 6s 8d) on 26 June. Another 5,000m was paid on 12

November 1329, 5,000m around 3 April 1330 and the final 10,000m

(£6,666 13s 4d) on 15 July 1330. Both parties therefore

kept their promises according to the treaty.

John Clavering, aged over 62, died without male heir in 1332, although

no inquest post mortem was carried out on his lands. This was

probably due to the agreement with Henry Percy (d.1352), which the king

ordered to take effect as John was dead on 23 January 1332 and Percy

had paid homage for these new lands of Warkworth castle, Rothbury and

Newburn with all his lands in Northumberland. The next year, on

29 July 1333, King Edward III stayed briefly at Warkworth when on campaign at Berwick on Tweed.

A year later on 24 September 1334, Henry Percy (d.1352) tried to ensure

his lands were enfeoffed to him in tail male, these included Alnwick

and Warkworth castles, these included Alnmouth, Long Houghton, Lesbury

and Chatton with land in Wooler held by Isabella Vescy as well as

Newburn held by Ralph Neville (d.1331) and the dower part of

Warkworth, Corbridge, Acklington and Rothbury with the

hamlets of Snitter, Birling, Thropton and Newtown held by Hawise

[Tibotot] the widow of John Clavering (d.1332), all in

Northumberland. However, the attempt was abandoned due to

previously enacted laws being violated by the grant, but the act was

later successfully carried out on 4 January 1335 with the exception of

the church advowsons.

John Glanton, on 1 November 1336, asked the king for recompense for the

time when he was constable of Warkworth castle and held the Scottish

prisoner of war, William Bard, there for 3 weeks short of 3

years. Presumably this had occurred recently during the wars of Edward Balliol

and before Percy took over the castle. Modern sources state that

Warkworth town, but not the castle was sacked in 1341, the same year

that King David II returned to

Scotland. This may well have happened for 3 years later on 19

October 1344, the men of many Northumberland parishes which included

Warkworth, Chatton and Rothbury claimed

that for the most part their

crops and other goods had been burned and otherwise destroyed and their

animals plundered by the Scots.

They therefore requested remission from the current taxation of a

ninth. The next year, on 18 February 1345, John Clavering's

widow, Hawise Tibotot died and her dower in Clavering

passed to her blood heir, her much married daughter Eva (d.1369).

The rest of the barony of Warkworth was now totally consumed within the

Percy honour with both Henry Percy (d.1352) and his son Henry (d.1368)

granting charters throughout their careers at Warkworth and indeed both

dying there.

The elder Henry Percy died on 26/27 February 1352. Soon

afterwards an inquest post mortem was carried out on his lands.

Within his many lands was the barony of Warkworth. This consisted

of the castle and manor with the towns of Birling, Acklington,

Rothbury, Newtown, Thropton and Snitter. These were all held of

the king in chief in fee tail by homage and fealty and by the service

of 2 knights. There then followed an extent of the castle and

manor. This included herbage of the castle moat, the pasture of

Wooler, rents from the towns of High Buston (Ourebotleston) and

Togston, a fishery in the River Coquet and a wood called

Sundreland. The extent of Acklington included the site of a chief

messuage, a windmill, park, and halmote, while Rothbury included 20

shielings (skalinge) in the forest and rent of burgages. Newtown

included a land called ‘Storeland' and a fulling-mill.

Snitter included a meadow called ‘Brademedwe' and a plot of land

called Chirland. Corbridge borough was held of the king in chief

in fee tail by fealty and by service of rendering £40 yearly to

the king for the old farm with a new increment of 10s. There was

also a plot of land called ‘Waldefleys,' a wood called

‘Lynels,' a plot of land called ‘Prendestretland,' a house

called ‘Tollebogth' farmed for 6s 8d pa, a plot of waste called

‘les Aldehals,' a yearly rent of 10s from the mill of Develeston

and two water-mills. Henry also held the advowson of the chapel

of St Mary in Warkworth. The chapel lay some third of a mile

south of the castle and was founded by Robert Fitz Roger (d.1214) and

given to the prior of Durham.

In the early fifteenth century the castle was where the Percy's planned their abortive overthrow of Henry IV which led to Harry Hotspur Percy being killed at the battle of Shrewsbury on 21 July 1403. After this his father, Earl Henry Percy (d.1408), was forced to surrender to the king at York.

In 1404 Percy was pardoned and returned to his northern castle, only to

rebel again in 1405. The result was King Henry IV (d.1413)

attacking the fortress with cannon. The king himself stated that

after 7 volleys of his artillery the well supplied castle

surrendered. It was then given to John Plantagenet (d.1435) the

later duke of Bedford. Earl Henry was killed in 1408 without

regaining Warkworth. In 1416 Henry Percy, the son of Hotspur, was

restored to his patrimony which included Warkworth. As earl of

Northumberland he was killed at the battle of St Albans in 1455 and his

son, yet another Henry, was killed at the battle of Towton in

1461. Both had supported Lancaster in the civil war. His

son, another Earl Henry Percy (d.1489), continued the family support

for King Henry VI (d.1471) and consequently lost the castle in the

fighting of the early 1460s. These campaigns are discussed under Bamburgh castle.

On 1 August 1464, the title of earl of Northumberland was given to John

Neville (d.1471), the brother of Warwick the Kingmaker. During

his 7 year tenure of the castle, he built the Montagu Tower, Neville

having the title Montagu from his grandfather, Earl Thomas Montagu of

Salibury (d.1428). After the death of the Neville brothers in

1471 the castle was restored to Henry Percy (d.1489).

Earl Henry Percy (d.1489) is said to have remodelled the castle and

began the building of the collegiate church in the bailey beneath the

motte. This work was abandoned on his killing in 1489. In

1536, Earl Henry's grandson, another Earl Henry (d.1537), bequeathed

all his estates to King Henry VIII (d.1547). Consequently the

king had his castle of Warkworth examined. The inquiry taken on

22 February 1538 found that Warkworth was:

A very proper house in good

repair. There is a marvellous proper dongeon of eight towers all joined

in one house, one of which needs repair. It rains very much in the

dining chamber and the little chamber over the gates where the Earl lay

himself. A new horse mill is wanted. Cost, £40 3s 4d and 4

fother of lead.

Around the same time Leland found:

Werkworthe castle stands on

the south side of the Coquet water. It is well maintained and

large. It belonged to the earl of Northumberland. It stands

on a high hill, the which for the more part is included with the river

and is about a mile from the sea. There is a pretty town and at

the town's end is a stone bridge with a tower on it. Beyond the

bridge is Banburghshire.

On 24 May 1543, the warden of the Marches reported back to the royal council that he had obeyed the king's instructions and had Alnwick

and Morpeth castles surveyed and had since decided to set up his main

centre of operations at Warkworth. He found the castle somewhat

decayed and out of repair. Consequently he had ordered it

‘apperrelled and put in redines' expecting it to be furnished for

his arrival in a week.

After its spell as a royal castle the fortress and the other Percy

estates were passed to Henry's nephew, who became Earl Thomas Percy of

Northumberland in the reign of Queen Mary (1553-58). In the next

reign he was executed for treason on 22 August 1572 following another

failed Pilgrimage of Grace. In 1567 Percy had ordered a survey of

the castle by George Clarkson. This found the castle in fair

condition apart from the great hall which had collapsed apart from its

east aisle, while the chambers and other buildings near them in the

bailey were found to be much decayed and threatened collapse unless

they were reroofed. After the earl's rebellion and defeat the

castle was occupied by John Forster (d.1602), the Warden of the Middle Marches,

who spoiled and wasted it, just as he did Bamburgh and Alnwick. The fortress was returned to the

earl's brother in the 1570s and he found that the roof of the old

drawing room, otherwise known as the solar in the bailey, was utterly

decayed and that the Carrickfergus Tower was in utter ruin.

Nearly 40 years later it was reported that the castle was in complete

ruin and used as a cattle fold with the gates open day and night.

The only part of the fortress still inhabitable was the great keep.

In 1617 King James visited the castle while his retinue explored the

ruins for an hour finding goats and sheep in nearly every chamber and

were ‘much moved to see it so spoiled and badly kept'. In

1644 the castle was surrendered to the Scots who remained a year.

Commonwealth forces occupied it again in 1648 and when they left they

took the doors and ironwork of the castle with them as part of the

slighting. In 1649 Algernon Percy applied for compensation for

the damage, but was allowed none. In 1672 the castle was stripped

of its remaining fabric when 272 cart loads of lead, timber and other

materials were taken from the keep alone. In 1698 it was decided

not to repair the castle when an estimate of £1,600 was given for

restoring the battlements, floors and windows.

Restoration occurred between 1853 and 1858 when Anthony Salvin was

employed to restore the keep. He partially refaced the exterior

and added new floors and roofs to 2 chambers on the second floor.

These then became known as the Duke's Chambers. Excavations took

place in the 1850s which uncovered the remains of the collegiate church

within the bailey. The Office of Works undertook excavations in

the moat in 1924 and this no doubt accounts for the excellent state of

the earthworks to the south of the castle.

Description

The motte of Warkworth castle with

its scarp blocks about 300' of the 750' wide neck of a sharp bend in

the River Coquet. The town then nestles in the loop of the river,

with a fortified fourteenth century bridge over the north end.

Other castles stand in similar positions, viz. Appleby, Caer Beris, Durham and Shrewsbury.

The motte itself is some 200' in basal diameter with a current summit

diameter of some 100'. This is now filled by the much later keep

which may have lowered and enlarged the original summit. The motte

itself is about 40' high, which ranks it with the largest in

Britain. As such it is probably a royal motte as only kings

tended to have the economic resources to build such giant

structures. The motte was surrounded by a ditch to all sides but

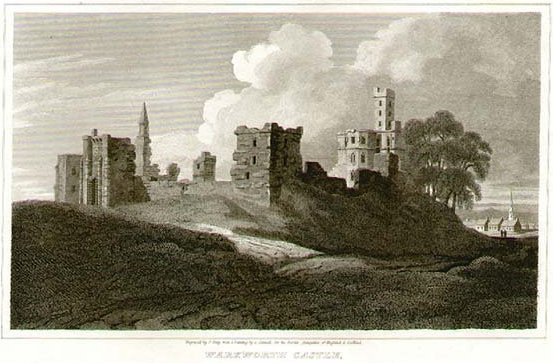

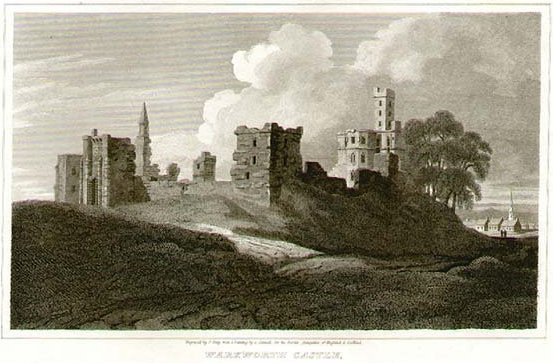

that to the north has been replaced by the current main road, as can be

seen in eighteenth century prints. Now there is merely a steep

scarp running down the main high street into the town towards the

church of St Laurence.

The ward of the original motte and bailey castle was about 250' east to

west by about 180' from the probable line of the motte ditch to the

south ditch. When the stone ward was constructed the eastern 70'

of the ward was abandoned, leaving a flat glacis which in eighteenth

century appeared to be merely a grassed over pile of rubble.

Presumably the original entrances were the same as today, the postern

to the north-west for access to the town and the main gatehouse to the

south.

The castle is supposed to have been first walled in stone with the bulk

of the curtain walls dating to this first masonry phase which is dated

to the rather precise and utterly unscientific dates of

1199-1213. This includes the gatehouse, Carrickfergus and postern

towers as well as probably an early tower under the site of the Montagu

Tower. There must also have been a stone keep on the motte,

though whether of the tower or shell keep variety is unknown.

Next the Grey Mare's Tail tower was added with the turret along the

east wall and subsequently the massive great keep and even later the

Montagu Tower. This was probably built on a new plan to its

purported predecessor which probably projected to the south like the

gatehouse and Carrickfergus tower.

The Gatehouse

The castle is still entered to the south via the twin towered

gatehouse. This is a most odd structure, apparently unique.

To the south are 2 projecting 20' diameter, half octagonal

towers. The 2 southernmost angles of each tower are further

protected by half octagonal buttresses. Large crossbow loops

pierce each of the 3 ground floor faces. These are long with

massive fish tailed oillets and short sighting slits towards the

top. Again, a unique feature of Warkworth. The twin

buttresses are chamfered at the base so they stand upon inverted

pyramids on the massive sloping plinth at the base of the towers which

progresses over half way down the ditch scarp.

The gate passageway is entered via an Early English arch of 2

orders. Unnaturally there are currently no portcullis grooves on

the walls, although there are twin ‘murder holes' in the ceiling

which would appear to be the remnants of the original twin

portcullis. Quite obviously the passageway has been relined and

possibly totally rebuilt with a pointed barrel vault inserted.

There are similarities to the late rebuildings at Skipton

here. The projecting corbel line supporting the moulded string

course over the gate has been taken as evidence that a drawbridge was

once raised to this position. If it were then all trace of the

mechanism has gone. If it were a turning bridge there is no trace

of an internal pit within the gatehouse.

Within

the passageway, defended by gates at either end, are 3 varied crossbow

loops on each side. Internally the final arches over the gate

passageway have gone, but the rear of both tower entrances remain - odd

Early English arches of 2 orders as are the other gate passageway

arches. Within the tower doorways are 2 long chambers with barrel

vaults similar to the gate passageway. They broaden out into the

towers at the south end. The floors within these have obviously

been raised, making the altered embrasures useless for combat.

Presumably this was done in the nineteenth century when this gatehouse

housed the castle custodian.

Within

the passageway, defended by gates at either end, are 3 varied crossbow

loops on each side. Internally the final arches over the gate

passageway have gone, but the rear of both tower entrances remain - odd

Early English arches of 2 orders as are the other gate passageway

arches. Within the tower doorways are 2 long chambers with barrel

vaults similar to the gate passageway. They broaden out into the

towers at the south end. The floors within these have obviously

been raised, making the altered embrasures useless for combat.

Presumably this was done in the nineteenth century when this gatehouse

housed the castle custodian.

Two external flights of steps to east and west curve up to what should

have been the constable's chamber on the first floor, but this has no

forward looking loops. However, there are what look like blocked

embrasures in both towers and a single large crossbow loop to the east

and west. Both towers had later vaults added at this level,

possibly to make the structure strong enough for artillery in the

Scottish fashion, viz Urquhart.

Internally the rear of the gatehouse has gone at first floor level and

the rough top of the inner wall to the south shows that the external

face of the gatehouse has been totally refaced and a later upper storey

added. Presumably this occurred where the buttresses have their

odd toppings. Internally the remains of steeply angled roof

creases remain to east and west, while in the towers on either side

were later chambers, above the earlier roof level. Above the gate

at the height of the roof are overhanging machicolations, somewhat

similar to those found over doorways at late Scottish houses, viz Hermitage and south of the border, Bywell. There are also beam holes for a hoarding.

A contemporary curtain wall ran off from the gatehouse to the

west. This had a fine sloping plinth and a later chapel on its

inside and other buildings, one possibly being a garret.

Carrickfergus Tower

Carrickfergus Tower

At the south-west corner of the enceinte stood the Carrickfergus Tower

which partially collapsed in the eighteenth century. Like the

gatehouse towers this was south facing and semi-octagonal, also having

loops on all three southern faces, though unlike the gatehouse, there

were no buttresses at the angles. The base of the tower has a

fine sloping plinth which runs almost to the base of the ditch, while

the interior seems to have been partially infilled as the fighting

embrasures would have been difficult to occupy. Also note the

state of these loops compared to those in the rebuilt gatehouse.

The bulk of the west side and most of the south side of the tower has

collapsed. The upper 2 storeys above the fighting level on the

ground floor were residential and there are traces of a garderobe as

well as fireplaces. The windows were also quite large, while all

the internal embrasures were shoulder headed. Such features do

not occur before 1250 and fade out after 1350. This rather dates

the tower at least 50 years later than the traditional dating and

suggests that this tower is younger than the Early English

gatehouse. The refacing of all this front may have taken place at

a very late date, possibly even post medieval.

The pointed entrance passage to the ground floor of the tower is an

obvious insertion, running at a odd angle diagonally through the south

curtain. There was an odd, corbelled out projection from the

tower at the north-west corner. Presumably the tower served as

withdrawing rooms from the great chamber to the north.

Lying along the west curtain, north of the Carrickfergus Tower, but

south of the great hall, lay a 2 storey building which housed the great

chamber at first floor level. The floor of this was supported on

3 central pillars, while narrow windows, now infilled, opened into the

bailey. The west curtain wall here is nearly twice as thick as

the curtain making up the west wall of the great hall to the

north. It also contains a mural staircase. The base of this

wall, although much patched, would appear to be the earliest of the

castle masonry. Two large windows set low in the wall are

probably later insertions, while the Romanesque recess, which contains

a carved panel over what appears to have been a large, rectangular

window, was possibly a balcony accessed from the solar.

Great Hall

The great hall consists of about half the length of the west curtain

before it makes a sharp angle to ascend the motte. The wall here

is on a slightly different alignment to the thicker curtain which joins

to the Carrickfergus tower. It is also set on a plinth topped by

2 sloping courses at the base of the newer work. Presumably this

is late fourteenth century. The internal junction is even more

obvious with a first floor Romanesque arch in the great chamber at the

collapsed junction, with a shoulder headed doorway beyond in the

hall. Above the change in wallwalk between newer thinner and the

older thicker curtain is also obvious.

The original hall was widened, probably in the 1380s, with the line of

the old wall being converted into an arcade with 2 of the pillar bases

of this surviving. There are also 2 stone fire pits in the floor,

which is odd considering there is a blocked arch in the west corner of

the south wall which is supposed to be the original ‘Norman'

fireplace. As the original hall would probably have been at first

floor level, this seems perplexing.

In the late fourteenth century, when the hall was extended eastwards, 2

square towers were built, the little stair tower and the Lion

Tower. The latter was named after the grumpy and rather

sheep-like Percy lion above the main doorway. Above this again

were the arms of Lucy of Egremont.

As Matilda Lucy, the second wife of Earl Henry Percy (d.1408), died in

1398, it would suggest that this tower and sculpture was made in the

last 20 years of the fourteenth century, perhaps to celebrate their

marriage which occurred in 1381.

North of the hall lay the ‘fifteenth century' buttery, pantry and

kitchen. Beyond these the curtain is much damaged before the

Postern Tower is reached. Beneath the rebuilt section are 2

relieving arches which may suggest the original collapsed into the

river.

Postern Tower

Postern Tower

The Postern Tower projects slightly from the curtains on either side,

while internally it has been much rebuilt and a spiral stair, now

destroyed, added to its north side. The Early English arch lies

upon a projecting string course and consists of 2 orders, the lower one

being rebated for a door. As no such rebate exists on the jambs,

which appear to be chamfered, it appears that this portal has been

rebuilt. The entrance is reached via a series of very worn steps.

Internally it is quite plain that the portal has been recently

rebuilt. Above the passageway are 2 further floors which appear

to have been hollowed out of the original structure and have nearly

square, probably fifteenth century windows. The battlements

appear of later date again and sport a curious cruciform loop to the

north.

From the postern a curtain ran straight up the motte to the new

keep. Presumably it would have originally reached an earlier

motte-top keep. Other than a boldly projecting buttress, which is

capped similarly to the gatehouse buttresses, the wall is pretty much

featureless, although there are traces of a late rebuilding towards the

motte top.

East Curtain

East Curtain

Running down from the south-east side of the keep is the east curtain

wall. For some reason this did not follow the path of the old

castle bailey, but took up a position some 70' west of the scarp of the

original ward, leaving a large glacis to the east. The curtain

ran in 2 uneven lengths to the south-east corner of the enceinte where

the Montagu Tower now stands. The main feature of the wall is

another boldly projecting buttress at the base of the motte. This

implies that both wingwalls are contemporary.

Running

down the motte the wall has no plinth although there is a single

chamfered offset on the level section. Between the eastern turret

and the Montagu Tower the wall gains a plinth with a sloped top course,

rather similar to some of the plinthing at Caernarfon. There is

also an inserted postern here in what must be a later section of

walling. Internally the postern is shoulder headed. Looking

down from the keep on the battlements of this wall it is rapidly

apparent that the inner face has been replaced, certainly at the top in

various late refurbishments. The same could well be true of the

outer face. Indeed an eighteenth century print of the castle

shows this curtain as standing at no more than half its current height

and the 'glacis' buried in debris.

Running

down the motte the wall has no plinth although there is a single

chamfered offset on the level section. Between the eastern turret

and the Montagu Tower the wall gains a plinth with a sloped top course,

rather similar to some of the plinthing at Caernarfon. There is

also an inserted postern here in what must be a later section of

walling. Internally the postern is shoulder headed. Looking

down from the keep on the battlements of this wall it is rapidly

apparent that the inner face has been replaced, certainly at the top in

various late refurbishments. The same could well be true of the

outer face. Indeed an eighteenth century print of the castle

shows this curtain as standing at no more than half its current height

and the 'glacis' buried in debris.

The battlements seem to have served the garderobe in the top of the

rectangular east turret. This has a his and her's entrance,

rather similar to that found in the east turret at Moreton Corbet castle which is thought to be Elizabethan. A 2 storey stables ran along the southern portion of the

curtain, while a well house with well over 60' deep lay just west of it.

Grey Mare's Tail Tower

Near the angle in the east curtain wall at the base of the motte stands

the semi-octagonal Grey Mare's Tail Tower. This appears to have

been inserted into the curtain, at least the junctions to the exterior

of the curtain are butted upon by the more brick shaped tower

masonry. The tower has the most extraordinary elongated crossbow

loops stretching over 12' high and graced with large fish tailed

oillets and no less than 3 sets of sighting slits. Internally

these loops are serviced by shoulder headed embrasures that make the

loops impossible to use and apparently stretch over 2 floors.

Obviously the interior of the embrasures have been ‘modified' in

the late rebuildings. Whether these extraordinary loops are also

late post military insertions is impossible to know, but seems likely

as the stone surrounding them appears slightly lighter than their more

golden surrounding stones.

In the sixteenth century the tower was used to hold prisoners and

contains some of their wall graffitis. The upper level of the

tower was blind, similar to some early thirteenth century drum towers,

like at White Castle. The

ground floor entrance to the tower was gained from a hall block that

ran against the curtain and is now largely destroyed. From here

steps were accessed to the south and a garderobe turret to the

north. The internal building also gave access to the upper floor

and the upper garderobe chamber of the attached garderobe turret.

The battlements again seem to have had a hoarding, but the darker

colour of their stone suggest they may be late additions.

An attempt has been made at dendrochronology on woodwork retrieved from

2 ‘window lintels' in the tower. Presumably these came from

the odd mutilated and rebuilt crossbow embrasures within the

tower. There was no crossmatching between the samples and no tree

ring dating evidence could be produced. However, radiocarbon

dating suggested an early fourteenth century date for the felling of

the timber. This was taken as evidence for the tower being early

fourteenth century, though in reality this seems merely guesswork and

wishful thinking.

Montagu's Tower

There should have been a tower at the south-east corner of the enceinte

judging from the current remains, but all that stands there now is the

square Amble or Montagu Tower. If it was built by Montagu

it most likely dates to between 1464 and 1471 when Lord Montagu held

the castle. However, there is no proof of this and its

alternative name is the Amble Tower as it faces nearby Amble. The

tower stands 4 storeys high with the basement reached down a short

flight of steps into a low room that has probably had the floor

raised. How this was used as a stable in the sixteenth century

seems odd for a room which would make a better dog compound than a home

for anything larger. The odd entrances into the ground floor on

the lower 2 levels suggest that some part of the lower level west wall

may be older than the rest of the tower. Fireplaces and

garderobes show that the sixteenth century tower was residential.

The curtain from the Montagu Tower to the gatehouse is a modern

reconstruction lying on older foundations. The toothing of it in

the side of the gatehouse show that this wall too was very thick.

Keep

Keep

Standing upon the old motte is a large and unusual tower keep.

This probably dates to the end of the fourteenth century and bears some

comparison with Trim keep in Ireland, it being a square keep with four

projecting towers set centrally in each face to form a 20 sided

keep. All the rectangular corners have been chamfered off.

Further the keep is not symmetrical, with all the turrets slightly off

centre and the central square tower itself being by no means a perfect

square.

Despite the initial similarity to twelfth century Trim keep,

Warkworth is well unique. It stands 3 storeys high on its motte

and was entered through the west face of its south turret. This

and the adjoining south-east corner of the central tower have

unfortunately been heavily rebuilt in the Victorian era, so the

original approach is uncertain, although there are traces of an

approach wall on the south face of the tower facing the entrance

portal. Externally the keep has a fine sloping plinth, which

would be necessary with it being built upon an unstable earth

mound. The chamfered off corners of the whole have been

interestingly geometrically shaped where they meet the plinth.

The ground floor of the tower has small loops, while the windows get

larger the higher up the wall they are set. On the top storey, on

the turret corner chamfers, are coats of arms set above a projecting

string course that makes an erratic course around the building.

On the northern turret, on the top floor where a window would be

expected, is instead a large relief of a heraldic Percy lion,

displaying itself in all its fury to the borough below. This is

certainly a better looking beast than the rather sad fellow on the Lion

Tower. Elsewhere are angels holding heraldic shields which would

once no doubt have been coloured. The last feature of note about

the exterior is the postern in the northern section of the west wall,

which no doubt like the nearby postern tower, offered a quicker way

down into the borough.

The internal features of the keep are quite spectacular and consist of

rectangular rooms in the 4 corners of the central keep, with long rooms

occupying the turrets back towards the centre of the main tower.

In the very centre was a rectangular light well that collected

rainwater. Entrance to the living quarters was gained from the

main doorway, into 2 successive entrance halls, the first controlled by

a porter's lodge. There was also what appears to have been an

oubliette or pit dungeon in the south-west corner of the central

keep. From the main entrance hall a great stairway doubled back

over the porter's lodge and up to the lobby above. This led into

the great hall in the south-east corner of the keep. North of

this, partially in the east turret, lay the chapel and beyond this to

the north the great chamber. The kitchen, buttery and pantry lay

in the western third of the keep and various mural service stairs led

to the lower floor below and battlements above. On the top floor

lay the duke's rooms in the south-west corner of the keep. This

was reroofed and made habitable between 1853 and 1858. Off centre

in the keep stood a watch tower which contains 3 floors of separate

rooms. The whole, though impressive looking, was utterly

indefensible to any siege artillery.

Within the bailey are the shattered remains of the foundations of the

fifteenth century colligate church. This is alleged to be a

similar build as the kitchen, chapel and great hall extension. It

has also been claimed that there are architectural similarities between

Warkworth's keep, Bolton Castle, and the domestic buildings at Bamburgh castle.

This has led to the suggestion that the ubiquitous John Lewyn was the

master mason responsible for building all these structures. He

certainly worked at Carlisle, Durham and Roxburgh,

but the idea that he was responsible for most building work in the

North during the fourteenth century seems to be stretching the

possibilities as far as the ‘history' of James St George has been

pulled.

Copyright©2022

Paul Martin Remfry

Within

the passageway, defended by gates at either end, are 3 varied crossbow

loops on each side. Internally the final arches over the gate

passageway have gone, but the rear of both tower entrances remain - odd

Early English arches of 2 orders as are the other gate passageway

arches. Within the tower doorways are 2 long chambers with barrel

vaults similar to the gate passageway. They broaden out into the

towers at the south end. The floors within these have obviously

been raised, making the altered embrasures useless for combat.

Presumably this was done in the nineteenth century when this gatehouse

housed the castle custodian.

Within

the passageway, defended by gates at either end, are 3 varied crossbow

loops on each side. Internally the final arches over the gate

passageway have gone, but the rear of both tower entrances remain - odd

Early English arches of 2 orders as are the other gate passageway

arches. Within the tower doorways are 2 long chambers with barrel

vaults similar to the gate passageway. They broaden out into the

towers at the south end. The floors within these have obviously

been raised, making the altered embrasures useless for combat.

Presumably this was done in the nineteenth century when this gatehouse

housed the castle custodian. Carrickfergus Tower

Carrickfergus Tower Postern Tower

Postern Tower East Curtain

East Curtain Running

down the motte the wall has no plinth although there is a single

chamfered offset on the level section. Between the eastern turret

and the Montagu Tower the wall gains a plinth with a sloped top course,

rather similar to some of the plinthing at Caernarfon. There is

also an inserted postern here in what must be a later section of

walling. Internally the postern is shoulder headed. Looking

down from the keep on the battlements of this wall it is rapidly

apparent that the inner face has been replaced, certainly at the top in

various late refurbishments. The same could well be true of the

outer face. Indeed an eighteenth century print of the castle

shows this curtain as standing at no more than half its current height

and the 'glacis' buried in debris.

Running

down the motte the wall has no plinth although there is a single

chamfered offset on the level section. Between the eastern turret

and the Montagu Tower the wall gains a plinth with a sloped top course,

rather similar to some of the plinthing at Caernarfon. There is

also an inserted postern here in what must be a later section of

walling. Internally the postern is shoulder headed. Looking

down from the keep on the battlements of this wall it is rapidly

apparent that the inner face has been replaced, certainly at the top in

various late refurbishments. The same could well be true of the

outer face. Indeed an eighteenth century print of the castle

shows this curtain as standing at no more than half its current height

and the 'glacis' buried in debris. Keep

Keep