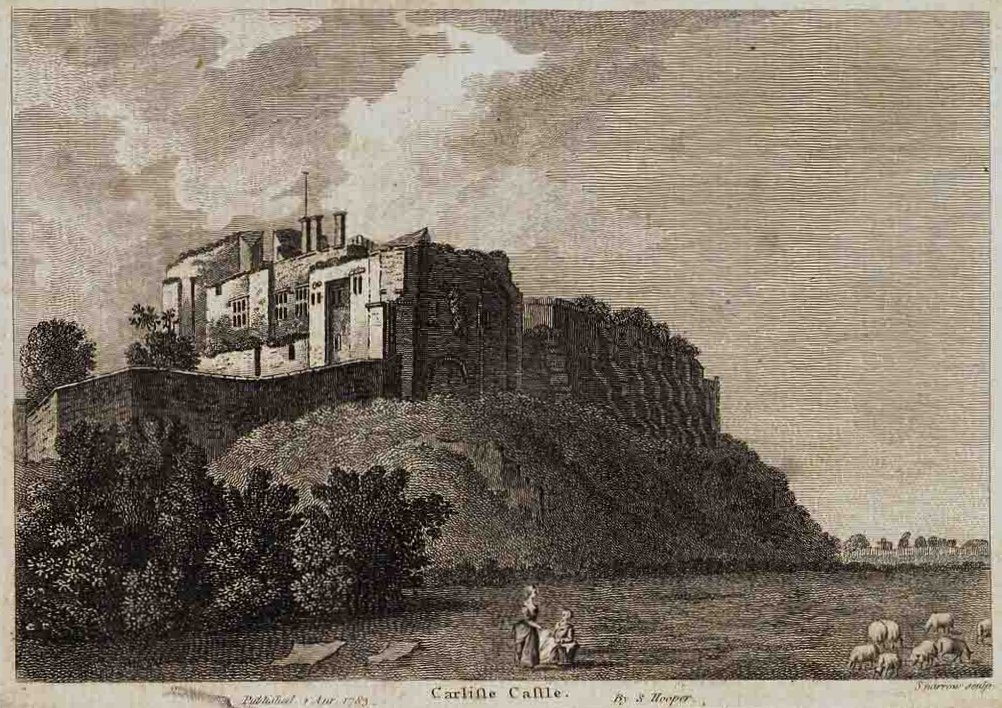

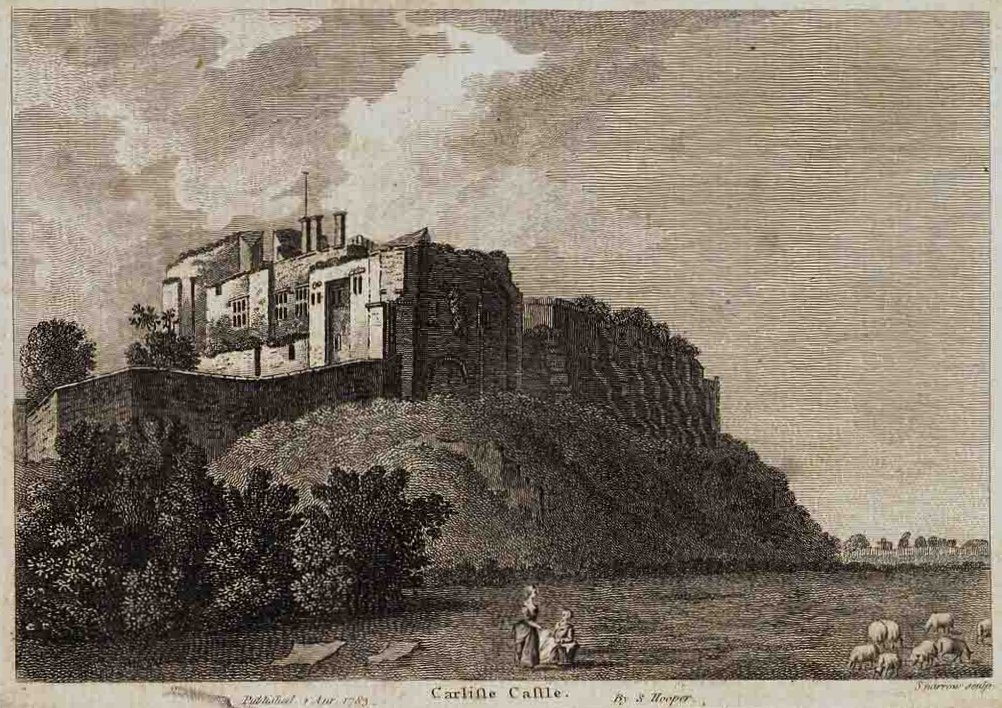

Carlisle

After Boudica's revolt a timber fort was founded at Carlisle

by

the Ninth Legion (Legio IX Hispana) at a site recorded as Luguvalium

around 72AD. Excavation south of the castle site discovered

the

line of the western and southern defences of this Flavian structure,

together with a waterlogged and therefore well preserved timber

gateway. Preserved writing tables record the fort name from

about

80AD. The choice of site was possibly because it could be

supplied by sea from the River Eden and occupied a ridge end site on a

steep river bluff commanding the junction of the Rivers Caldew and

Eden. At the same time as the foundation excavation has shown

a

Flavian settlement under the present city. Multiple

rebuildings

are thought to have occurred and the fort was mentioned around 105AD in

a tablet from Vindolanda which attests to a civilian

settlement.

This new fort was a part of the new Tyne-Solway frontier along the

Stanegate.

After the Roman withdrawal from Britannia, Cair Ligualid

was listed among the 28 cities of Britain in Nennius. In 685,

when King Ecgfrith attacked the Picts, St Cuthbert (d.687) came to ‘Lugubalia,

which is corruptly called by the English Luelto

speak to the queen, who was there awaiting the result of the war in

her sister's monastery. The next day the citizens took him to

see

'the walls of the town and the remarkable fountain, anciently built by

the Romans'. It would appear from this that the

city defences and even some of the Roman waterworks were still

functional. The death of King Ecgfrith that year may have

made

the town's future more uncertain, but it would appear to have been

still functional in 876 when it is thought the Vikings laid waste the

town, or at least plundered it, when Halfdan divided up the land of

Northumbria and harried and pillaged it.

The early history of northern castles of Britain is even more obscure

than those of the south of the island. King Edmund (d.946)

seems

to have taken control of the Carlisle district in 945 when he wasted

all Cumberland before

giving it to King

Malcolm of Scotland (d.954) in return for him acknowledging that he was

Edmund's ally by both sea and land. Despite later claims to

the

contrary there is archaeological evidence that the town of Carlisle

continued as a functioning entity from the time of its founding by the

Romans. It would also seem possible that the Roman walls

remained

standing as late as this. In Wales Giraldus Cambrensis

describes walking through Caerleon:

Many

vestiges of its former

nobility might yet be seen, immense palaces, with gilded roofs formerly

the exalted pride of the Romans, built in prodigious size, with a

gigantic tower, distinguished thermal baths, the remnants of temples

and the sites of theatres, all enclosed within excellent walls, which

are yet partly standing. You will find on all sides, both

within

and without the circuit of the walls, subterraneous buildings, water

pipes, and underground passages. And, more remarkable than

that,

stoves contrived with wonderful art to transmit the heat through narrow

flues up the sides of the walls.

In other words, Roman ruins were probably in the condition that many

Norman castles are today. Coin finds in Carlisle include

pennies

of Aethelstan (924-939), Edgar (959-975) and Aethelred II

(978-1016). Excavation has also indicated that the area where

the

castle now stands was occupied throughout this period and served by

maintained Roman roads.

In 1070 fighting was occurring between Earl Gospatric of Northumberland

(d.1074) and King Malcolm

III of Scotland (d.1093), with them wasting one

another's properties along the border. During these troubles Malcolm

subjugated Cumberland

by violence and no

doubt took possession of Carlisle. In 1072 King William of

England (d.1087) deprived Gospatrick of his earldom and made King

Malcolm (d.1093) his man, probably leaving him in command of Cumberland

as part of the Scottish kingdom. The Carlisle Chronicle,

drawn up

using ancient chronicles in 1291 to help Edward I (1272-1307) determine

the right king of Scotland, stated clearly that in the time of Earl

Siward (d.1055) King Malcolm of Cumbria (d.1093) ruled to the River

Duddon (Dunde).

Thirteenth century sources state that the boundary between Scottish

Cumberland and

England lay at ‘the King's Cross on Stainmore'.

This lay

between the castles of Brough

and Bowes.

Quite clearly from this Carlisle was recognised as a part of Scotland

before the Norman Conquest, even if Northumbrian rule had formerly held

sway here at times. The district was only brought fully under

Norman

control when William

Rufus (1087-1100) took and fortified Carlisle in

1092 with a large army, expelling its previous lord, Dolfin, said to be

a younger son of Earl Gospatrick (d.1074), but possibly more likely his

son in law. According to the Peterborough Chronicle written

some

20 years later:

1092

King William travelled north to Carlisle (Cardeol)

with a very great army and restored the burgh and raised the castle and

drove out Dolfin, who earlier ruled the land there and set the castle

with his men and afterwards returned south and sent very many peasants

there with women and livestock to live there and to till that

land.

This would appear to have been copied by later chronicles, namely

Waverley and Henry Huntington. A separate source seems to

have

been shared by 2 contemporary chroniclers, Florence of Worcester and

Symeon of Durham. They recorded:

This

done, the king [Rufus] set out for Northumberland, the city which the

British call Carlisle and the Latins Lugubalis;

he restored and built a castle in it. For this city, with

some

others in those parts, was destroyed by the Danish pagans 200 years ago

and up to this time was left deserted.

As has been stated above, the city was not abandoned prior to the

Norman arrival and this source is most definitely wrong about the place

being a wilderness. The question is, what did Rufus actually

do

there other than found a castle? By the sounds of it he drove

away the original inhabitants and replaced them with people more likely

to be loyal to him. Similarly the texts give no clue as to

what

form this castle commenced by Rufus may have looked like.

After the conquest of 1092, either William II or more

likely Henry I

(1100-35), gave the lordship of Carlisle to Ranulf le Meschin (d.1129),

who in 1120 became earl of Chester.

Part of the grant may have taken place as early as 1098 when Ranulf

married Lucy Bolingbroke

(d.1138), the widow of Ivo Taillebois (d.1094/7) and Roger Fitz Gerold

(d.1097/98). This marriage also brought him Taillebois' land

of Appleby and possibly

also Kendal.

That Henry I

was holding Carlisle at his accession in August 1100 is likely as he

seems to have founded Carlisle priory, an event that would not have

happened if Henry was not lord of Carlisle. A few years later

Ranulf le Meschin decided to found his own priory at Wetheral, some 7

miles to the east of Carlisle priory, an event that would probably not

have happened if King Henry had not already of founded Carlisle priory

in what was later to become Ranulf's caput.

Ranulf, as nephew to Earl Hugh Lupus of Chester

(d.1101) and cousin to Earl Ranulf of Chester (d.1120), helped control

the family's north-western portion of the kingdom of England which

covered England from the Shropshire border to the Solway

Firth.

During his time as lord of Carlisle he was said, in 1212, to have

created 2 border sub-lordships or baronies at Burgh

by Sands and Liddel

(Lydale)

covering the land north of Carlisle. The first of these was

given

to Ranulf's brother in law, Robert Trevers and the latter to Turgis

Brandos. According to Camden writing some 5 centuries later,

Ranulf tried to give Gilsland to his brother, William (d.1130/5), but

he failed to dislodge its ruler. No evidence of this alleged

grant exists in the pipe rolls or the Testa de Neville of 1212 and as

such it can probably be dismissed. However, Ranulf certainly

gave

his brother, William, the lordship of Allerdale (which then seems to

have included Copeland) and stretched along the coast between the

rivers Duddon and Esk (and therefore including Millom,

Egremont, Cockermouth and Burgh by Sands).

Ranulf was a prominent supporter of Henry I

and led the first battle of the royal army at the battle of Tinchebrai

in 1106. It was probably around this date that Ranulf granted

Wetheral (Wetherhala)

to St Mary's abbey, York.

This led to the founding of Wetheral priory. Ranulf then

endowed

the priory with this churches of St Michael and St Lawrence in his

castellum of Appleby.

On the earl of Chester's death in 1120, it is thought that Henry I

resumed Carlisle lordship when he made Meschin earl of Chester in his

cousin's place, although there is no direct evidence as to when this

happened although it was certainly before 1122 when the king went to

Carlisle after Michaelmas and ‘sent money for the

fortification

of the place with a castle and towers'. By the time of the

September 1129 pipe roll, Carlisle lordship had been divided into 2, Chaerleolium and Westmarieland.

Hildret was holding Carlisle and accounted for £14 16s 6d

from

the old farm, ie last year, and the king's manors. The costs

of

making a wall around the city had cost £14 16s 6d cancelling

out

the income from last year. Presumably these works had been

going

on since 1122. It was also recorded that the canons

of St

Mary of Carlisle had received £10 towards the building work

of

their church as well as being pardoned 37s 4d, while a further

£6

2s had been spent on the city walls. The city and castle were

obviously well garrisoned for payments were made to the knights and

sergeants of Carlisle at a cost of £42 7s

7½d. As

£21 was paid for 1 knight, 10 serjeants, a watchman and a

porter

in Burton in Lonsdale, it

suggests that

Carlisle garrison was double that. At this time it would

appear

that Copeland was independent of these 2 fledgling shires.

Three

years later in 1133 King Henry made Prior Adulf of Nostlia bishop of

the newly created see of Karleol

giving to the diocese the churches of Cumberland

and Westmorland which were under the archdeaconry of York.

The death of Henry I

on 2

December 1135 was a sea change for Carlisle. Early in 1136, King

David of Scotland (d.1153), cynically remembering his oath to

King Henry I

(d.1135), invaded the kingdom of England swiftly taking various

garrisons in Cumberland

and Northumberland, and advancing on Durham,

while bypassing Bamburgh

(Babhanburch).

King Stephen,

when he was staying at Oxford

at the end of the festival of the Nativity, was told how:

"King David of the

Scots, on

pretence that he was coming with peaceful intent for the purpose of

visiting you, has come to Carlisle and Newcastle

and stealthily taken both". To this the king is said to have

replied, "What he has taken by stealth, I will recover by victory" and

without delay the king moved forward his army, which was so mighty and

valiant and so numerous that none in England could be remembered like

it. However King David met him at Durham

and made a treaty with him restoring Newcastle,

but retaining Carlisle with the king's consent. David did not

do

homage to King Stephen because he had previously, as the first of the

laity, promised on oath to the Empress...

to maintain her in possession of England after the death of King Henry I.

However, Henry,

the son of King David, did homage to King Stephen on

which he was presented with the borough of Huntingdon by way of gift.

Other sources state that King

Stephen came to Durham

on 5 February and after 15 days received David in Newcastle castle where they

made peace with David's son, Henry, paying homage to King Stephen at York for the honour of Huntingdon

without Doncaster (Dunecastra)

or Carlisle (Karleol).

According to the fifteenth century Bower's chronicle, after the peace

of Newcastle, King David

went immediately to Carlisle where he is said

to have made a very strong castle as well as raising the most powerful

walls for the city. This, of course, ignores the contemporary

chronicles that state that King

Henry I

did just this in 1122. As such this late claim should

probably be

ignored, despite the fact that the castle keep is claimed as his based

on this solitary story.

Although Rufus

and his brother, King

Henry I,

had built Carlisle castle it was now a property of the Scottish kings

and their adherents. In 1138 the papal legate arrived at

Carlisle

and returned the seat to Bishop Aldulf. Quite obviously he

had

been forced to flee the district with the coming of the

Scots.

The legate also freed all the captives from the war that he found in

the town. These captives well enough explain the bishop's

flight,

he fairly obviously not wanting to be counted amongst them.

Around this time King David

confirmed to Robert Bruce all Annandale (Estrahanent

which would now be Strath Annan) which stretched from the boundary of

the lands of Dougal Stranit to that of Ralph Meschin (the nephew of the

Ralph below, d.1138). Further the lands were to have the same

customs as Carlisle and Cumberland

were held in the days of Ralph Meschin (d.1129, but relinquished

Carlisle to King Henry

in 1120). The apparent mention of Ralph (d.1138) would

indicate

that this charter probably dated to the time from 1130, around when

William Meschin the father of Ralph died, until his own death in 1138.

In 1140 Earl Ranulf of Chester (d.1153) became King Stephen's

enemy

after he failed to have Carlisle taken from King David's son, Earl

Henry of Huntingdon (d.1152), and returned to himself as heir

of his

father, Earl Ranulf (d.1129) who had been lord of Carlisle before

1120. Although Earl Ranulf (d.1153) eventually plotted with

both

sides in the civil war, he failed to oust the Scots from Carlisle,

though this was from no lack of trying.

The story of what happened in Carlisle during the Anarchy of 1136-54

can be partially reconstructed from using chronicle evidence.

However, the trouble with relying on later chronicles is again

emphasised when the chronicler Hoveden's account of this era is

examined. According to him Henry Fitz Empress

(1133-89), the grandson of Henry I (d.1135) and claimant to the throne

against King Stephen, being 16:

and

having been brought up at

the court of King David

of the Scots, his mother's uncle, was dubbed

knight by David in the city of Carlisle, having first made an oath to

him that if he should become king of England he would restore Newcastle

and all Northumbria between the rivers Tweed and Tyne to him.

After this Henry, by the advice and assistance of King David, crossed

over into Normandy and being received by the nobles was made duke of

Normandy.

In reality Henry had been in Normandy for much of this youth and was

not brought up at the Scottish court, or had even been there before

1149. In that year Henry made his way to Carlisle where he

was

dubbed knight on Whit Sunday. To this ceremony came Earl

Ranulf

of Chester (d.1153) and there the earl made his peace with King David,

accepting the latter's control of Carlisle. In return David

granted Lancashire to Ranulf, which shows that William Fitz Duncan, the

previous lord of the district, had recently died. The allies

then

made an abortive attack upon York

before Henry

retired to Normandy. Hoveden reasonably well knew the facts

of

the story, but he obviously made some unlucky guesses in trying to fill

in some of the gaps.

King David seems to have found Carlisle convenient and was

perhaps the

most visited place in his kingdom. Finally, on 24 May 1153,

King

David died in his castle of Carlisle. His final hours were

recorded by Ailred of Rievaulx. He stated:

On

Wednesday 20 May 1153 (20

May was a Thursday!), though all his limbs were heavy with the weight

of illness, nevertheless he walked into the oratory as he was wont,

both for mass and the canonical hours, but when on Friday his malady

began to get worse and the violence of the disease had robbed him of

the power of standing as of walking he summoned the clerks and monks

and asked that the sacrament of the Lord's body should be given to him;

and on their making ready to bring him what he ordered, he forbade

them, saying that he would partake of those most holy mysteries before

the most holy altar. When, therefore, he had been carried

down

into the oratory by the hands of clerks and knights and the mass had

been celebrated he begged that a cross he reverenced, which they call

the black cross, should be brought forward to him to worship....

At last

he was brought back into his chamber... and when the priests came... he

rose up as best he could and threw himself off the pallet upon the

ground as he received the healing rite with so much devoutness....

It would seem likely that this oratory was the one still extant in

Carlisle castle keep. David's death was followed a year later

by

that of King Stephen.

His successor, Henry

Fitz Empress

(d.1189) wished to turn the clock back to 1135 when his grandfather

died. He therefore required back from the Scottish king,

David's

grandson, Malcolm IV

(d.1165), the northern counties of England.

Consequently in July 1157, King Malcolm surrendered Cumberland to the king when

the 2 met at Peak castle.

Henceforward Carlisle appeared in the pipe rolls as a royal

county. The next year, 1158, the king, with his army, met King

Malcolm at Carlisle by 24 June and, after arguing with him,

refused to

make him a knight although he did knight, William the son King Stephen and

lord of the eastern castles of Castle Acre

and Eye.

However this dispute did not lead to hostilities. With this

the

castle became a bit of a backwater with Anglo-Scottish relations

stable. In 1163 Henry visited his northern stronghold again

and

in 1165 the sheriff spent 10s 6d ‘on the work of the gates of

Carlisle'. Three years later in 1168 £2 was spent

on

removing (remouenda)

the gate of Carlisle (Cardel)

castle. Presumably this work included the building of the new

gatehouse and the closing of the old one to the east of the inner ward.

In 1173 King Henry II

was suddenly faced by a concerted attack by all his enemies.

One of these was King

William of Scots who sided with the young king, Henry III

(d.1184). Asking his barons for counsel concerning battle

they are said to have answered:

Sire, king of Scotland,

Of all your rights

Carlisle is the most difficult;

And since the

young king is willing to give you all,

Go and conquer the

capital, we advise you thus;

And if Robert Vaux

will not give the chief town,

From the old high

tower you must have him thrown.

Lay siege to it

and then make your great assembled host

to swear not to

stir from it till you have seen the city on fire,

The master wall

pulled down with your pickaxes of steel,

Himself fastened

to a high gallows.

Then you will see

Robert Vaux toeing the line...

But

Robert Vaux defended himself bravely;

the son of Odard

was not at all behindhand...

Royal records show that by September 1173 £20 had been

accounted

to Constable Robert Vaux of Carlisle (d.1194) for keeping a number of

knights in Carlisle castle. At this time a knight could be

paid

anything from 6d to 1s per day, although about 8d seemed to be normal,

while £20 was equal to 4,800d. That same September

the

sheriff accounted for the munitioning of the castle. As well

as

stocking provisions the castle ditch was worked upon at a cost of 45s

4d and 67s worth of work was carried out at the castle under

the

supervision of Adam Fitz Robert and his father Sheriff Robert Fitz

Troite (d.1174), Ralf the clerk and Wulfric. Wulfric the

engineer

was one of a small group of military advisors employed by Henry II,

so his involvement meant that the king was serious about the defence of

Carlisle. At some point a further 100 loads of wheat were

shipped

into the castle at a cost of £6. The damage done to

the

county was also estimated that September at £27 6s 6d allowed

for

the wasting of the county during the war, and 30s for the destruction

of the mill of Tanerez

wasted by war. However, this was not the end of the matter,

for the next year the Scots returned.

That they could see Carlisle full of beauty;

The sun

illuminates the walls and turrets....

When they arrived a message was sent to the

castle:

"Go to Robert [Vaux], say that I send him this message:

Surrender me the

castle this very momnet:

He will have no

succour from any living man,

And the king of

England will never more be his defender;

And if he will not

do so, swear well to him

He shall lose his

head for it and his children shall die.

I will not leave

him a single friend or relation

Whom I will not

exile, if he does not execute my command."

Now go the barons

demanding the truce,

And he answered

him: "Friend, what is it you want?

You might soon

leave there the little and the great."

And said the

messenger: "That is not courteous:

A messenger

carrying his message should not be

Insulted or ill

treated; he may say what he likes."

And said Robert

Vaux: "Now come nearer,

Say your pleasure;

be afraid of nothing."

Sir Robert Vaux,

you are valiant and wise...

Restore him the

castle which is his inheritance:

His ancestors had

it already long in peacefulness;

but the king of

England has disinherited him of it

Wrongly and

sinfully, thus he sends you a message by me....

Surrender him the

castle and all the fortress,

And he will give

you so much coined money

Never Hubert Vaux

had so much collected.

"Surrender him the

castle on such terms,

And become his man

on such conditions;

He will give you

so much property in fine gold and money,

And much more than

we tell you.

If you do

not consent to it to disinherit him,

You must not in

any place trust to his person:

He will besiege

the castle with his people,

You will not go

out of it any day without injury to you,

Nor all the gold

of his kingdom which he could collect,

To prevent you

from drawn on a hurdle and adjudge to a bad death."

Robert refused this command and told King

William to send to King

Henry

and if he allowed it, Robert would willingly surrender castle and

town. Otherwise he and his men were steady and would consider

themselves disgraced if they surrendered as long as they had victuals

sufficient to last them out. On hearing this reply King

William,

instead of attacking Carlisle, leaving a portion of his army behind,

marched on Appleby and Brough and rapidly took both

castles.

Now cut off from the outside world Vaux sent a message to Richard Lucy

(d.1179), the father in law of Reginald Lucy (d.1200) of Egremont and Odinel

Umfraville (d.1182) of Prudhoe.

Richard replied that Robert should hold fast as King Henry

himself would soon be in England to deal with the rebels.

Regardless of this advice, Robert agreed to surrender on 29 September

if he had not been relieved. To condense Fantosme, the Scots

crossed the Pennines from the siege of Wark

and came back to Carlisle with King

William threatening Robert Vaux

with being torn to pieces if he did not yield the castle and offering

him riches if he did. Vaux said he was not to be bribed and

was

not afraid as his castle was well provisioned and his men were firmly

behind him. Consequently the Scots, rather than risk a full

assault left half the army to besiege Carlisle and with the other half

set off to take Liddel, Brough and Appleby. William

again summoned Vaux to surrender and Richard Lucy, after hearing from

him, told Henry II

that ‘neither wine nor wheat can get to him any more nor will

help reach him from Richmond;

if he does not get aid quickly he will be starved out'.

However Richard had told Vaux that Henry II

would be back in England in a fortnight. On the strength of

this,

Robert agreed to surrender if no aid arrived because he knew that

relief would shortly be on its way.

A contemporary chronicler recorded his take of events.

Meanwhile

King William of

the

Scots besieged Carlisle, which Robert Vaux had in custody.

And,

leaving a portion of his army in besieging the castle, with the

remainder he marched through Northumberland, devastating the lands of

the king and his barons. And he took the castles of Liddel, Brough (Burgo), Appleby, Warkworth (Wercwrede) and Harbottle (Yrebotle)

which was held by Odonel Umfraville, after which he returned to the

siege of Carlisle. Here he continued the siege until Robert

Vaux,

in consequence of a deficiency of provisions, made a peace with him on

the following terms, that at the feast of St Michael next following [29

September 1174], he would surrender to him the castle and town of

Carlisle, unless in the meantime he should obtain succour from his

lord, the king of England. Truly, the king of Scots departing

thence, laid siege to Odonel Umfraville's castle of Prudhoe, but was unable to

take it, for Sheriff Robert Stuteville of York,

William Vescy, Ranulf Glanville, Constable Ralph Tilly of the household

of the archbishop of York, Bernard Balliol [Barnards

Castle] and Odonel Umfraville,

having assembled a large force, hastened to its relief. On

learning of their approach, the king of Scots retreated thence and laid

siege to William Vescy's Alnwick

castle

and then, dividing his army into 3 divisions, kept one with himself and

gave command of the other 2 to Earl Duncan and the earl of Angus and to

Richard Morville

[constable of Scotland], giving them orders to lay

waste the neighbouring provinces....

The result of William splitting his army proved disastrous.

On 13 July 1174 he was caught unprepared before Alnwick castle

and captured, thus bringing Carlisle's war to an end. Before

that

same September, Robert Fitz Truite, the sheriff of Cumberland since

1158, seems to have died, possibly as a result of disease from the

siege. Consequently his son, Adam Fitz Robert, who had been

undersheriff with his father, rendered his account for the year which

was nothing on account of the war; to which a sceptical clerk had

added, so he says!

After the war of 1173-74, Cumberland

and Westmorland were

reorganised

into counties with Reiner the dapifer of Ranulf Glanville accounting

in 1177 for the 3 years rent and being allowed £58 2s 8d for

the

custody of the castles of Westmorland. Presumably these were Appleby and Brough

castles which pertained to the sheriffdom. The same year it

was

recorded that Adam Fitz Robert Truite and Robert Vaux had no idea of

how much money they had spent during the war. Consequently

their

sergeants were to ‘access how much they received in past

years as

they do not know'. Despite this, Robert Vaux paid

£112 4d

into the treasure after rendering an account of £342 12d for

the

farm of Cumberland

for this year and the last 2.

With this the history of Carlisle castle fell back into obscurity until

1186 when:

King

Henry formed an army to

attack Roland Fitz Uchtryd of Galloway, but the prince came to Henry at

Carlisle to make peace, Henry then offering Paulinus of Leeds the

bishopric of Carlisle, enhanced by the churches of Bamburgh and Scarborough as well as the

chapelry of Tickhill

and the king's 2 manors near Carlisle, but he refused.

As a result of Henry's visit work was undertaken, probably to build a

chamber (camere)

at a cost of £26, while the work of the bridge cost a further

62s

7d. It is thought that this chamber was the hall that lay

between

the keep and Queen Mary's Tower along the south curtain.

Certainly in 1307 ‘the new stone tower for the king's

chamber'

was built and this was almost certainly Queen Mary's Tower, which

confirms the identification. Expenditure continued in 1187

with

the works of the king's chamber in Carlisle castle and a little tower (parve turris)

costing £41 14s 7d. A further charge of 10s for

felling

material for mending the timberwork of the great tower was made by the

same writ. This wood would appear to have been for the final

stage of the works in 1188 when £13 6s 8d in repairing the

king's

chamber and planking the tower (planchianda

turri).

A further 77s 6d was spent to complete the aforesaid chamber.

This was the last work carried out on the fortress during the reign of Henry II (1154-89).

In 1190 the new government of Richard

I

(1189-99) had work undertaken to the 3 gates of the city of Carlisle

and its granary at a cost of 119s 5d. A further £14

was

spent on unspecified works at the castle the next year, 1191.

The

government had obviously been worried about the security of the

northern forntier for in 1192 it was recorded that Sheriff William Fitz

Aldelin had received £60 for the custody of Carlisle castle

for

the past 3 years. In 1196 the castle jail was repaired for

40s

and work was undertaken on the castle gate for 100s, while in 1197 work

was carried out on the castle chapel as well as the bridge between the

castle and town at a cost of 112s 6d. Finally in 1198, works

were

carried out on the houses of the castle for 40s. However, it

was

noted nearly a century later that the sheriffs of Carlisle had

regularly been claiming £2 or £5 for the upkeep of

the

castle houses, but they had usually appropriated the money for other

uses.

The reign of King John

started in some trepidation in the spring of 1199. Fear of

disturbances on the death of King

Richard led to Sheriff Hugh Bardolf (d.1203) of Westmorland

taking over Cumberland

and spending £36 15s on knights and serjeants for the custody

of

the homeland, while William Stuteville (d.1203) demanded £7

9s 8d

for the time he spent in Carlisle castle. With the initial

panic

over Carlisle castle was stocked with provisions in September

1200. No doubt this store would have proved of use when King John

himself visited the castle in late February 1201. Possibly as

a

result of the visit the castle was strengthened before that September

with £27 14s being spent on making repairs and attachments to

the

ditches and palisades. Maintenance continued the next year

when

£47 was recorded as spent on castle works at September

1202. The next year, September 1203, £61 10s 9d was

spent

in the repair of the gates and king's houses and £12 on the

sustenance of knights in the castle. By September 1204 a

further

£116 4s 1d had been spent on repairs to the castle and 50m

(£33 6s 8d) in supplying the garrison with wheat, bacon and

other

necessities. This was followed on 28 Nov 1204, by the king

sending 60m (£40) to Constable Roger Lacy of Chester, the hero

of

the defence of Chateau

Gaillard,

to munition Carlisle castle. The official order for Roger

taking

over the constableship of the castle was issued to its previous

constable, Robert Courtney (d.1209) on 1 December. On 8 March

1205 Roger was reinforced by the sending of 8 royal crossbowmen to

him. Simultaneously supplies of wheat were ordered from the

lands

of Landa Seburweh and Richard Gernun (d.1234+) to be sown for the use

of the castle garrison. On 12 April 1205, the king further

ordered that Roger was to have wood from Carlisle forest in aid of

repairing the royal castle of Carlisle.

In February 1206, King

John again stayed at Carlisle. He was at Bowes

on 16 February and had arrived at Carlisle by the 18th. He

then

remained there until at least the 20th before going on to Lancaster

by the 21st. He returned again in 1208, staying at Hexham on

1

August, before being found at Carlisle on the 17th and then being at

Whinfell by the 19th. He was back again 4 years later,

staying at

Wigton on 21-22 June 1212, then Carlisle from the 23rd to the 26th,

before moving on to Hexham on 27th.

In 1212 John had an inquisition carried out. This recorded

that

in Carlisle one Albert Fitz Bernard held 1 carucate of land by the

sergeanty of making the city gates. Similarly the sergeanty

of

Nicholas Gerbad, Alice his wife as well as Richard Carpenter and

Matilda his wife, meant that they held a suburb of Carlisle for which

they had to have the gates of Carlisle shod in iron. Possibly

this sergeanty dated back to the time of Henry I's

refortification of

Carlisle in 1122.

On 13 April 1215, Robert Roos of Helmsley,

custodian of our castle of Karleol,

was allowed £60 for holding the castle for the past 3

years. He was also granted the vills of Sowerby, Karleton and

Wifrightebe on 10 April, until his lands in Normandy could be

recovered. On 24 July 1215, Roos was replaced by Robert

Vipont

(d.1228) of Appleby, Brough, Brougham and Pendragon

castles, as sheriff. He held this appointment, although Ralph

de

La Ferte had been briefly constable until 7 January 1216, until 11

February 1222, when he was replaced by William Rughedon and Walter

Mauclerc. During the time of Robert's sheriffdom he was

recorded

as alienating the castle garden.

With the collapse of Magna Carta and the civil war renewing, on 7

February 1216, the barons of the Exchequer were ordered to allocate to

Robert Vipont payments for the knights, sergeants and crossbowmen he

had with him in our castle of Carlisle which had been repaired and

garrisoned by him, by the view and testament of honest men.

This

was obviously a necessary measure as Norham

castle

had been besieged and taken by King William on 19 October

1216.

He had then taken the homage of the men of Northumberland on 22 October

at Felton. The attack continued through the winter with

William

burning the towns of Mitford

and Morpeth on 7 January, Alnwick

on 9 January and Wark on 11

January. In reply to this royalist forces took the town and

castle of Berwick on 15

January and Roxburgh

on the 16th before burning Dunbar

and its surrounding villages on the 18th. Finally, in

February

1216, King Alexander

burned his way into the province of Carlisle, his

troops reaching as far as Holme Cultram before being chased back by

English forces who came to Carlisle burning the rebels' lands as far as

that city.

In July King Alexander II

returned to besiege Carlisle with all his army

apart from any Scots from whom he received scutage instead.

The

implication of this is that Alexander did not want ‘wild'

Scotsmen destroying Carlisle and preferred their money to pay for more

reliable English troops to sooth the feelings of the citizens he wanted

to rule. On 8 August the city surrendered to him and was

occupied, although as yet Alexander did not attack the

castle.

Writing seventy years later, the religious of Carlisle remembered

events thus.

King Alexander of the

Scots moved angrily against the city of Carlisle and the citizens

handed it over to him because King

John had inflicted many injuries upon them and not long

afterwards he had obtained the city and fortress by force.

Two of the injuries John had inflicted upon the citizens of Carlisle

would seem to be a refusal to allow them to be freefarm in 1202 and a

massive tallage of 550m (£366 13s 4d) in 1210. Of

the

assault on the castle nothing was recorded other than the above

chronicle statement that the castle was taken by force, presumably in

the August of 1216. All that can be said with certainty from

later repairs is that the attackers seem to have smashed their way in

through both the outer gatehouse, otherwise known as Ireby's Tower, and

then the inner gatehouse, these and the otherwise unidentified

Maunsell's tower, had all been consequently wrecked.

Presumably

this all happened before King

John

died on 19 October 1216. As the outer gatehouse was known as

Ireby's tower and William Ireby was lord by marriage of Gamblesby and

Glassonby from John's reign well into

that of Henry III

(1216-72), it

is to be presumed that he gave his name to the outer gatehouse, though

whether this was through defending it, building it, living in it or

repairing it, is unknown. Further, William was a grandson of

the

Gospatric Fitz Orm (d.1185) who surrendered Appleby

castle to the Scots in 1174.

Nearly a year later on 23 September 1217, the regent, Earl William

Marshall (d.1219) instructed the archbishop of York and the bishop of

Durham, the earls of Chester, Derby and Aumale [William Fortibus,

d.1241, was also lord of Cockermouth],

Constable John of Chester (d.1240), Geoffrey Neville (d.1249), Brian

Insula (d.1234), Hugh Balliol (d.1229), Philip Ullecot (d.1221) and

Roger Bertram (Mitford,

d.1242), that as

King Alexander

had not returned Carlisle castle to Robert Vipont

(d.1228) with all the lands he had hostiley taken in the war between us

and the Lord Louis. Consequently they were ordered to recover

Carlisle and the lands and prisoners taken by force if

necessary.

Soon afterwards, after the retreat of Louis from England around 29

September, all the barons of England paid homage to King Henry III.

After this, King

Alexander, before he was acquitted of his

excommunication, voluntarily returned Carlisle to the English

kingdom. This was probably in December 1217 when the

archbishop

of Canterbury went to Carlisle and accepted seisin of the castle from

Alexander for the use of the king of England. The archbishop

then

handed the castle to the sheriff of Cumberland.

By 28 June 1221, Robert Vipont (d.1228) was building houses at

Carlisle. Presumably these were within the town, rather than

in

the castle, although just a year later on 29 June 1222, Sheriff Walter

Mauclerc (d.1248) was ordered to repair the houses of the castle by the

view of honest men. Mauclerc had been appointed sheriff on 5

April 1222 when all the royal castles in England were resumed by the

Crown in the aftermath of the civil war of 1215-17. Walter

also

received 100m (£66 13s 4d) pa for custody of the

castle. On

taking charge of the fortress Walter found the place devoid of supplies

and had to accept gifts of flour and a tripod mounted crossbow for the

garrison and oxen for the demesnes from Thomas Multon (d.1240), the

lord of Egremont.

The same winter on 9 October 1222, 3 royal crossbowmen and 4 sergeants

were sent to garrison the castle. The men were then regularly

paid, last receiving money on 27 July 1223. Presumably the

crossbowmen being paid off occurred at the same time as Sheriff Walter

Mauclerc was elected bishop of Carlisle about 22 August 1223.

Despite this, he remained sheriff until 1233, although he often had an

undersheriff. Sheriff Walter also received the pannage of

Cumberland forest on 15 October 1222, to sustain himself in the royal

service in Carlisle castle. That September 1222 the sheriff

was

credited with £10 for repairing the king's houses in Carlisle

castle. This was followed on 18 February 1223, with an order

to

mend (emendacionem)

the tower

of Carlisle castle by the view of honest men at a cost of up to 20m

(£13 6s 8d) and on 2 May to use timber from Cumberland forest

for

joists for both the keep and the castle houses. Again on 17

June

he was ordered to make further repairs to the keep.

Presumably

this accounts for the 20m (£13 6s 8d) allocated for works on

the

castle that September.

Works were still needed at the castle in 1226 when on 26 February, the

sheriff was allowed to spend up to 100m (£66 13s 4d) in

repairing

the leading and joists of the keep. This work had oviously

begun

by 24 March 1226, when the sheriff of Cumberland was authorised to have

timbers taken from the forest to repair the castle keep. This

work may have been finished by 20 July 1226, when the sheriff was

ordered to make a jail in the castle for a cost of up to 10m

(£6

13s 4d). The cost of this duly appeared in the September pipe

roll as did payments of £42 12s for 1226 and £40

for 1225

as well as £30 for 3/4 of 1224, allocated to Bishop Walter

for

having custody of the castle. By September 1227, the 100m

(£66 13s 4d) authorised in 1226 had been spent on the joists

and

lead for roofing the keep. Further, repairs had been carried

out

to the castle houses at a cost of 55s 9d. The bishop had also

been awarded an extra £4 6s 11d by king's writ to finish the

100m

(£66 13s 4d) work enjoined upon him for his custody of the

castle

and county. From 1228 to 1232 work was regularly recorded on

repairing or mending the castle houses, 100s in 1228, £8 6d

in

1229 which also included repairs to the city gate, £4 14s 9d

in

1230, 115s in 1231 and 100s in 1232. In 1232 the sheriff was

ordered to construct a circuit of palisading around the castle, while

the city received a grant of murage to assist in upkeep of

walls.

In the January of 1233 Bishop Mauclerc fell from favour with the

overthrow of Earl Hubert Burgh. On 6 February the king

instructed

his new sheriff, Thomas Multon of Egremont

(d.1240), to have Carlisle castle blockaded if it had not surrendered

to him in a fortnight, while the bishop's lay possessions were

seized. However, Walter duly surrendered his offices and

fined

£1,000 for having peace, surrendering his royal charters of

possession and retiring into temporary ‘exile overseas on

account

of the injuries he had done to the church and kingdom'.

Sheriff

Thomas Multon then spent 51s 7d on repairing a breach in a turret (turella)

and in repairs to the walls which the sappers had undermined when King

Alexander of the Scots had besieged the castle.

Finally, he spent

£8 8s 5d for costs in tin and lead used for covering the

castle

[roofs]. In 1235 the sheriff claimed another 20s for

repairing

the king's houses in the castle and an undefined amount in garrisoning

the fortress.

In the 1237 treaty

of York, the king of Scots resigned his claim to the border

counties of Cumberland,

Durham, Northumberland

and Westmorland,

acknowledging the current boundary between the 2

kingdoms. This led Henry

III to instruct his sheriff of Northumberland to spend as

little as possible on Newcastle

and Bamburgh

as ‘the king is not now in fear of his castles as

before'.

It would seem likely that the same attitude was held for Carlisle,

although again it was recorded that Thomas Multon had garrisoned the

castle as was customary. The same year William Dacre became

sheriff and received 1 tun of wine worth 40s at the castle.

For

the next 2 years, 1238-39, he received 100s for emending the king's

houses in the castle. In the latter year he also reroofed the

keep and the king's chamber with lead and repaired other minor defects

for a cost of £8 10s 6½d. Further work

continued in

1240 with repairs to the moat bridge, the stairs to the great chamber

and the larder for 48s 4d. A further 100s was allocated for

mending the king's houses within the fortress. As has been

noted

these 100s payments seem likely to have simply been pocketed.

With the threat of war with King

Alexander II (d.1249) in 1244, Gerard the

Engineer was allocated £10 for building the king's engines in

Carlisle castle, while a further 6s 4d was spent repairing the castle

houses. Simultaneously the king ordered the sheriff in March

1244

to have the tower at the castle gate repaired along with the part of

the wall which had lately fallen down and to have the castle chapel

wainscotted and glazed. Ten oaks were to be cut down in

Inglewood

in aid of this wainscotting. By 4 June the king was intending

to

come to Carlisle in person for he ordered 10 tuns of wine bought at

Boston to sent to Carlisle castle ‘so that the king may find

them

on his coming there'. The same September 1244 repairs had

been

carried out to a turret and the houses within the castle and also

amendments had been made to the houses at a cost of 27m (£18)

by

the view of Robert Clerk. One and a half tuns of wine were

sent

to stock the castle in 1246, but the condition of the fortress was said

2 years later to be dire.

On 1 May 1248, Richard and Ralph Levinton together with William

Feugers, were ordered to go to Carlisle castle and view in what state

John Balliol, to whom the king has committed the castle, received it

[from Sheriff William Dacre]. On 18 July 1248, Sheriff

Balliol

was ordered to repair the king's hall and other buildings in the

castle. The next year it was noted that Sheriff John Balliol

was

receiving 100m (£66 13s 4d) per annum for having the custody

of

the castle. In 1250 it was further noted that Sheriff Dacre

had

spent £10 in emending the king's houses in the castle during

his

last 2 years of office. It also becomes clear at this time

that

100s or £5 per year seems to be the going rate for

‘mending' the royal houses in Carlisle castle, this amount

being

allowed to the sheriff for that purpose on most years between 1249 and

1259, £5 spent on castle each year, however only 19s

5½d

was spent in 1252!

Some repairs were ordered

to Carlisle castle

on 16 May 1253, when oaks were ordered cut down for timbers for the

king's houses. On 26 May 1255, orders were given to make

necessary repairs to the king's houses, an order repeated on 20 May

1255. Soon afterwards on 22 August 1255, Robert Bruce

(d.1295)

was appointed to keep the castle of Carlisle with the county of Cumberland.

Soon after this Robert reported the castle so ‘greatly

dilapidated' that he recommended that the money collected for Crusade

should be stored elsewhere for its safety. Regardless, his

appointment to Carlisle did not last long and on 28 October 1255 the

king committed the county of Cumberland

and the castle of Carlisle during pleasure to Earl William Fortibus of

Aumale (d.1260), the lord of Cockermouth

castle.

Soon after Earl William took over the fortress a report was sent to the

king from Thomas Lascelles (the heir of William Ireby) and other

knights of the county of Cumberland.

At the royal command they had visited and inspected Carlisle castle and

its condition when it was delivered by Robert Bruce (d.1295) to Earl

William Fortibus of Aumale (d.1260). They

found it in a bad condition:

...all

the lead gutters of

the great tower were decayed and the doors and shutters

likewise.

The joists and planking were broken and rotten and the walls of the

tower were in a bad state for want of mending and covering.

The

queen's chamber, which was covered in lead, needed great repair and

covering and the chimney needed instant repair or it would speedily

fall on the chamber, which is a very great danger. Maunsell's

turret and the turret of William Ireby and the turret beyond/over the

inner gate, were levelled and deteriorated in the time of the

great war of King John

and were

never afterwards rebuilt or repaired. The chapel, great hall,

kitchens, granges, stables, bakeries, breweries and the houses beyond

the gate and the bridges within and without the castle needed repair

and covering beyond measure. There was a great crevice within

the

turret of William Ireby from the summit to the base, requiring repair

anew, which was shown to Sir Henry Bathon with the other defects named

above. Some bretasche which was within Maunsell's

turret was

newly blown down by the wind, and was now burned and so were the doors

and shutters of the great tower and of the stables and kitchens and the

bolts of the doors with their ironwork carried off. Great

part of

the paling within and without the castle was likewise burned and

destroyed...

Despite the poor state of the fortress the only order for its repair on

20 October 1261, amounted to cutting oaks for timbers to fix some

defects and work on the palisading. The same day the bailiffs

and

good men of Carlisle were granted murage for 5 years.

Obviously

this was for maintaining the walls which were over 150 years old and

not for building a new enceinte around the city. This should

be

borne in mind when other murage grants are used to date town walls.

In 1262 the new sheriff, Eustace Balliol (d.1272), accounted for nearly

£100 spent on building 2 great catapults which had been made

in

the city and moved into the castle where they could be placed under

cover. This was at a time of great tension in the kingdom as

the

Barons' War began. This caused Eustace much expenditure in

holding his northern fortress against the rebels.

Unfortunately

much of what occurred has not been recorded, but in the 1285 Cumberland

forest eyre it was recorded that in July 1265, John Deiville (d.1291)

and his men ‘in wartime occupied Carlisle castle by force

from

Eustace Balliol and released the prisoners in his custody in the same

castle...'. Certainly on 5 August 1264 there is a hint of

fighting in the north. On that day the king, a captive of the

reformers, wrote to the northern royalist barons, John Balliol (Barnards Castle, d.1268),

Peter Bruce (Kendal,

d.1272), Robert Neville (d.1271), Ralph Fitz Randolf (Middleham, d.1270), William

Greystoke (d.1289), Roger Lancaster (d.1291), Stephen Meynell (Whorlton,

d.1264+), Adam Gesemuth (d.bef.1274, the husband of Christiana, the

daughter of William Ireby (d.1257)), Gilbert Haunsard (d.1291), Eustace

Balliol (d.1272, the captain of Carlisle), Nicholas Boltby (d.1272) and

Robert Stuteville of Ayton (d.1265), to come to the king at London with

their horses and arms and give counsel with the baronage against the

invasion of the [royalist] aliens or face the king's

indignation.

He also noted that they had claimed that they could not come due to the

enmity of John Deiville (d.1291), John Vescy (Alnwick,

d.1289), Thomas Multon (of Gilsland, d.1271) and Gilbert Umfraville (Prudhoe,

d.1307) who were attempting to attack them. The king had

therefore written to them to desist in pushing their grievances and

therefore those commanded were to come to London at once. It

is

quite obvious from this that Cumberland

was in a state of civil war, just like the rest of the

country.

The war at this point went the rebels way as on 6 January 1265, Balliol

was ordered to hand Carlisle castle over to Thomas Muleton (d.1271) as

was asked by the council of barons.

With the victory of Prince Edward over the barons at the battle of Evesham

on 4 August 1265 the castle was soon reclaimed by the royalists in the

form of the younger Robert Bruce (d.1304), the father of King Robert I

of Scotland. On 4 October 1265 he was ordered to turn the

castle

and county over to Roger Leyburn, who held it until 10 January 1267,

when he was ordered to return it to Robert Bruce (d.1304). It

was

only now that work was undertaken on the castle with the tower and

other buildings been repaired in 1269 at a cost of some

£12. For this 12 oaks were cut down for work on the

hall

and other houses. In March 1271, another 20 oaks were

supplied

for repairs to the keep. In 1272 it was recorded that the

exchequer and sheriff's offices were in the outer gatehouse.

The

purposes the office was put too, however, seems to have been far from

just. Between 1272 and 1274, it was alleged, probably with

justification, that William Ribton, the sergeant to Sheriff Robert

Creppinge, with his approval forced an approver imprisoned in the

castle to accuse several innocent men of serious crimes so that they

could be blackmailed into paying for the withdrawal of the

charges. Further in 1279, it was found that every holder of

office of sheriff since 1261, with one exception, had not spent the

100s allowance regularly claimed for the maintenance of the king's

houses on the castle.

In 1280 King Edward

came to Carlisle and spent over £23 on food

for his household and horses as well as £7 3s spent on

building a

new bridge. Two years later in 1282, 9 prisoners escaped from

the

castle prison after killing the janitor and his son.

Presumably

this prison was in the castle outer gatehouse. In 1283

Sheriff

Gilbert Corewenne claimed that over the last 2½ years he had

spent £12 10s on castle repairs. More works

occurred in the

period 1286-88 when over £200 was spent on the

castle. In

1287 this work amounted to some £115 and included 30 oaks fit

for

timbers from Inglewood forest for castle works on 28 January and

another 30 oaks on 23 October.

The castle was lucky to survive the next conflagration that scourged

Carlisle. On 25 May 1292 a fire swept through Carlisle and

its

suburbs, consuming the cathedral church with fire and burning

everything right up to the castle, whose bridge was

destroyed. On

18 August the king ordered 16 oaks fit for timber to be taken to

Carlisle castle ‘to repair the bridge... which was lately

burned

accidentally'. The same year The Great Cause of who ruled

Scotland began. This was to plague the British Isles for

centuries.

In 1295 King Edward

ordered siege engines constructed and for minor

works to be made to the castle. These proved necessary for on

26

March 1296, Earl John Comyn of Buchan (d.1308) with the earls of

Menteith, Starthearn, Lennox, Ross, Athol, Mar, together with John

Comyn of Badenoch (d.1303), suddenly invaded England and for 2 days

violently besieged Carlisle city, but could not take it. That

day

was Easter Monday and rather parallelled another sneak attack made 14

years before at Flint

and Rhuddlan.

According to a local chronicle, a Scottish spy called Patrick escaped

from the castle prison and started a fire. However, the

townsmen

put out the fire while the women held the Scots from the wall with

stones and boiling water. Without artillery and the coup de

main

having failed the Scots withdrew back to Annandale, although they

burned everything in Cumberland

as far as Cockermouth.

Two years later, on 13 October 1298, Bishop John Halton replaced Robert

Bruce (d.1304) as constable of the castle. Soon afterwards

the

Multon of Egremont

holdings Burgh by

Sands, Rockcliffe, Irthing and Brampton in Gilsland were

attacked and

burned, their value being reduced from some £219 to

£53. Also attacked around the same time was Bewcastle.

Finally, on 11 November 1298, William Wallace (d.1305), after burning Liddel,

Levington and Gilsland, appeared under the town walls on 7 November and

tried to bluff the garrison to surrender. When they wouldn't

and

Wallace saw the firm condition of the castle and their defensive

military arsenal, the Scottish army retreated, having destroyed the

houses and gardens under the castle walls. After

this the

castle was reinforced by 14 crossbowmen and 95 foot, while new

brattices were erected around the walls, the 3 bridges were remade, the

ditches were cleaned out both within and without the fortress and the

stonework of the walls and gates repaired. Surprisingly only

£20 was sent to finance these works, while on 20 September,

20

oaks were sent from Inglewood forest to repair the castle houses,

bridges and battlements. Sixty young pike were also sent to

stock

the castle moat. From this time on the castle was used as a

supply depot for the Scottish war, although the mills were used to

grind corn for the armies, while wine was stockpiled in a warehouse

built within the castle with 174 cartloads of timber.

Wallace's

attack was followed in 1298 with repairs to the walls around the gates

and the houses over the castle gate as well as glass for the king's

chamber and chapel and works on the great hall. Oddly, the

same

year the sheriff stated that he could not produce 3 men charged with

homicide as they were imprisoned in the castle ‘the keeping

of

which the bishop of Carlisle has by the king's commission' even though

the prison remains in the sheriff's keeping.

Two years later in 1300, Carlisle was the base for the famed Caerlaverock

campaign. In 1301 the roofing of keep was again repaired and

prisoners from Turnberry

castle

were imprisoned within it by chains and fetters bought for the

purpose. As a final precaution iron bars were placed across

the

windows. The year also saw work on the great hall and siege

engines stored within the fortress. In 1302, the sheriff was

still complaining that he could not have ‘free entry or exit

at

the castle gate'. The same year repairs were made to the

great

gate and the roof of the queen's chamber. In 1303 further

repairs

were made to the lead of the great tower and 33 rods of wall in the

outer bailey were made as well as brattices for the main gate and a

postern ‘against the coming of the Scots in the

Marches'.

It was probably the next year, 1304, that Sheriff John Lucy complained

that the prison had collapsed and consequently he was having difficulty

gaining access to the castle, as neither he nor the gaoler had any

residence in it and that there was nowhere in Carlisle city or castle

to hold the county court. Possibly this complaint led the

castle

being handed back to the sheriff from the bishop in May 1304.

In 1305/6 the prison with the house above it was rebuilt at cost of

nearly £20. When King

Edward heard of the murder of John

Comyn at Dumfries on 10 February 1306, he sent a force of horse and

foot to Carlisle and Berwick

in order to

protect the border. In this action he proved correct for Robert

Bruce immediately invaded the parts of Galloway loyal to Edward I and

burned the land, besieging one of the chief men in a lake, possibly Loch Doon castle.

However, part of the Carlisle garrison sallied out into Galloway and

caused him to raise the siege and retreat after he had burned the

engines and ships he had made for the siege. The same year,

1306,

a wooden chapel and bath was built for the queen when Edward I

stayed at the priory and Queen Margaret in the castle. On 17

February 1307, Thomas Bruce's head was displayed on top of the keep

after he, his brother Alexander, and Reginald Crawford, had been

defeated in battle at Loch Ryan. At the same time a

parliament

lasting 2 months was held at Carlisle. After Edward left

Carlisle

to invade Scotland once more, he got as far as Burgh

by Sands where he

died on 7 July 1307, leaving the Scottish rebellion uncrushed.

Edward II

(1307-27) may then

have ordered further work at the castle for in 1308 repairs were made

to a breach in the wall near the castle postern and new chambers were

built by the little postern and at the outer gate. Two

bridges

were also repaired inside the castle. Monies to the value of

£208 5s 7d were expended on breaking freestone from Wetheral

quarry, as well as on the wages of masons and others assisting them in

making 2 stairs, one for 2 turrets on the high tower where springalds

were positioned and another in a new stone tower attached to the king's

chamber which had 2 portcullises and double vaulting. This

was St

Mary's Tower, set in the east corner of the inner bailey,

‘which

tower was 28' above the ground when Alexander (Bastenthwayt) was

removed from office. And beside that same tower were built 2

little stone chambers, a fireplace and 2 garderobes, so he

says'.

During this year, 1308, the sheriff claimed allowance for 4 men at arms

and 10 archers stationed within the fortress. Further, on 12

November 1312, that since 1310 £20 pa had been allocated for

keeping Carlisle castle and county safe.

These recent improvements made to Carlisle castle proved necessary as

the Scottish rebellion drew nearer to England. In August

1311,

after an attack had been launched on Gilsland, the castle garrison was

increased with 8 knights and 156 men at arms being hired during

October. That December 1311 there were an extra 10 men at

arms,

20 serjeants in haketons (leather jackets reinforced with chain mail)

in the castle, vill and Marches of Carlisle which were normally held by

15 knights, 31 squires, 7 men at arms, 6 hobelars and 100

archers. Then, in May and June 1313, up to 100m

(£66 13s 4d) was allocated to repair the castle houses, while

20

oaks were cut down for the king's works there. In late April

1314, before the battle of Bannockburn on 24 June 1314, Edward Bruce

harried Cumberland as

they had refused

to pay the agreed tribute they had given hostages for.

However he

refused to attack Carlisle due to the number of soldiers assembled

there.

After Bannockburn the earl of Hereford with a contingent that included

Anthony Lucy of Allerdale, a claimant to Cockermouth,

withdrew towards Carlisle, but were captured at Bothwell castle.

On 8 July 1314, Carlisle castle garrison was recorded as 4 knights, 50

men at arms, 30 hobelars and 80 archers supported by 3 companies

comprising a total of 3 knights and 34 men at arms. In

September

15 Irish hobelars and 40 foot soldiers together with 2 troops of

English foot, one of 160 which arrived on 30 Sept and another of 20 on

24 September arrived to increment the garrison. On 26 October

1314, a further 3 men at arms were sent from the king's court to help

garrison Carlisle vill. Presumably all these forces were

still

present when on 22 July 1315, King

Robert Bruce attacked Carlisle city

gates by speed and surprise. However, the garrison was ready

for

the attack, forcing the attackers to assault with ladders, a sow for

mining, fascines for filling ditches, portable wooden bridges on wheels

for crossing moats, a stone thrower and a belfry. On the

fifth

day of the siege the stone thrower attacked the Caldew gate and city

wall, but to little effect as to meet this the garrison deployed 7 or 8

stonethrowers and springalds. The wooden belfry was then

brought

up, but the garrison within had built a counter belfry and placed it

against the wall which the Scots had to attack. However, the

attacking machine stuck fast in the mud without reaching a position in

which to launch an assault. Possibly this and the failure of pontoon

bridges to cross the moat as they sank under their own weight, was due

to the inclement weather of the era. General assaults on the

town

on the last 2 days of the siege achieved little so on 1 August the

Scots withdrew, harried by the garrison. After the withdrawal

of

the Scots the king on 21 November ordered his sheriff to have the new

chamber within the castle covered in lead as well as to repair the

fortress houses and to have other houses made to store the king's

victuals there. Presumably this resulted in the September

1316

record that nearly £15 had been spent on the castle

palisades,

woodwork, the roofs of the great hall and its kitchen and the building

of a new chapel in the outer ward as well as on the windows of the

queen's chamber and various ‘engines'. Further, 6s

8d was

spent on roofing in lead part of the new tower in the inner

bailey. Finally, further work was ordered on 28 September

1316

with the sheriff being ordered to spend up to 10m (£6 13s 4d)

on

repairing the walls and houses of Carlisle castle.

In 1318 Anthony Lucy (d.1343) took over the castle as

sheriff. In

the subsequent survey the surveyors found that the great hall for the

king's household in the outer bailey of the castle with a great chamber

and garderobe at one end and a pantry and buttery at the other, had

defects which, together with carriage and wages of carpenters, could

not be repaired for less than £12 as they say that the great

timbers below the boards of the partitions were broken by the wind and

are largely rotten and that most of the hall, chamber, garderobe,

pantry and buttery which are roofed with shingles have been unroofed by

the storm and most of the shingles remaining on the roof are rotten and

that the timber below, boards and shingles, are broken and rotten and

cannot be usefully repaired. They found in the same [outer]

bailey 2 chambers for knights and clerks whose defects in heavy timber,

partitions and roofing cannot be repaired for less than

£4... They further found that the springald on the

new

tower needed repair as did the turrets on the keep and the brattices on

the walls [hoardings]. Elsewhere the bakery, brewery and

garderobe of the queen's chamber had been unroofed, while the forge in

the inner bailey had been ‘virtually knocked to the

ground'. Also the main gate needed to be renewed with the

re-vaulting of the gatehouse going to cost £20 and

more. On

the west side of the castle, facing the Caldew bridge near the church

of the Holy Trinity where the Scots had set up their stone thrower in

1315, the wall was ‘threatened with ruin' and needed to be

demolished and rebuilt from the foundations up at a cost of 1,000m

(£666 13s 4d), but as this was out of the question they

suggested

that a palisade should be built inside the segment at risk for 20m

(£13 6s 8d). The total of repairs suggested came to

just

under £70. In reply to this, on 21 September 1318,

the

sheriff was licensed to spend just £10. During

1319,

repairs were made to the great brattice by the great tower as well as

roofing the new tower with lead. Repairs were also made to

window

frames and the gutters of the castle houses.

On 25 May 1321, 100m (£66 13s 4d) was paid to Robert Barton,

‘appointed to supervise and repair the defects of Carlisle

castle'. These defects were listed in July 1321, when it was

found that a wall 40' long had collapsed and another 120' long was

about to collapse in the outer ward near the Caldew bridge.

The

conclusion was that demolition was needed and then the wall need to be

rebuilt on new foundations with supporting stakes. This wall

was

to have 4 small and 2 large buttresses and would cost an estimated

£240 not least because the stone from the old wall was too

small

to be reused except as a filling. Meantime, to cover the

fallen

and ruinous wall a palisade 220' long and 32' high should be made for

£50. It was again noted that the stone vault over

the main

gate was falling out and now had to be propped up on beams, while the

gate planks were so rotten that it needed remaking anew. Also

required was the replacement of 4 great joists and 20 great planks in

the upper room of the chamber in the great tower; the repair and

roofing of 4 wooden turrets; the roofing of the new tower in lead,

while various sections of timber and masonry were in need of repair and

the turrets on the roof were ‘begun when the new tower was

made

and not yet finished which need to be finished, the stone and woodwork

of which cannot be done for less than £4. Finally,

the

foundations of the queen's chamber needed attention. The

total

cost of the works was estimated to be £453. This

included a

wooden shelter 60' square ‘in the manner of a pentice' for

the

masons to work under and which was afterwards to be used as a

stable. That same year, 1321, repairs were carried out to the

gutter of the queen's chamber. Finally, after 21 June 1321

and

before 28 August 1322, nearly £220 was spent on the

castle.

These works included trees cut for boards and laths, workmen digging

stone and repairs to ‘the tower and the houses in the castle

and

the fences and walls both inside and out'. Consequently in

October 1321, Sheriff Andrew Harcla (d.1323) reported that many faults

had been ‘well and durably repaired' but there were still

‘many great and dangerous faults, namely in the walls, which,

without great provision, cannot be repaired'. It would seem

that

as the tower on the Caldew gate side of the outer bailey was later

called ‘Harkeleyes', this was probably part of his work.

In the spring of 1322, Earl Thomas of Lancaster was decisively defeated

by Andrew Harcla at the battle

of Boroughbridge on 16 March and, as a reward, Andrew was

made earl of Carlisle by Edward

II

on 25 March. Even with his new authority, Harcla was unable

to

protect his county and in July 1322, the Scottish army lay around

Carlisle for 5 days wasting the country, but made no attempt on the

city or castle. After the defeat of Edward II at the battle of Byland on

14 October 1322, Earl Andrew Harcla of Carlisle made a personal peace

treaty with King Robert

Bruce at Lochmaben

on 3 January 1323. He then returned to Carlisle and, calling

the

chief men of his earldom to him, he made them swear to uphold his

peace. When this became known to the king and his government

the

earl was proclaimed a traitor and the king sent word to Sir Anthony

Lucy to take Harcla and he would be rewarded. Consequently,

Anthony entered the undefended Carlisle castle on 25 February 1323 as

if to converse with the earl on business. With him came 3

powerful knights, Hugh Lowther, Richard Denton and Hugh Moriceby with 4

good men at arms and others with arms concealed under their

attire. As they entered the castle they detached armed men to

keep guard in both the inner and outer parts of the castle.

They

found the earl dictating letters in the great hall, and they being

armed and he unarmed, forced him to surrender. Someone in the

earl's household shouted, "Treason! Treason!" and the porter at the

inner gate tried to shut it against Lucy's men until Denton cut him

down. At this the remaining Harcla men in the castle

surrendered,

although one man rode off to announce to the earl's cousin what had

occurred. Lucy, meanwhile, sent word to the king of his

actions.

Six days after the earl's arrest the king's men at arms arrived at

Carlisle under Geoffrey Scrope (d.1340) who the next day, 3 March, sat

in judgement on the earl within his own castle. They found

him

guilty and in the name of the king ordered him stripped of his

dignities, hanged, beheaded, disembowelled and his entrails to be

burned. His head was to taken to London, his body quartered

with

the parts going to be suspended on the tower of Carlisle castle, Newcastle on Tyne, Bristol

and Dover.

For his actions Anthony Lucy was made lord of Cockermouth.

Despite the renovation works in 1321-22, it was found by 22 November

1323, ‘that the walls of the castle and city are in many

places

so out of repair and fallen down that it is necessary to make a wooden

peel about the places until the time when the defects can be repaired

with a wall of stone and lime'... so as many oaks and leafless trees as

are needed will be delivered to the sheriff for this work.

This

was duly done at a cost of £8 17s 9½d.

The next year

on 24 April 1324, £200 was ordered taken from rebel lands in

Yorkshire and Lancashire and given to Constable Anthony Lucy for castle

works in Carlisle. This was followed on 12 June 1324, by

Robert

Barton, the late keeper of the king's works at Carlisle, being ordered

to deliver to Constable Anthony Lucy all of his implements fit for the

work in repairing the walls, houses, towers and other things at the

castle and that the town walls should be repaired too. Four

days

later on 16 June 1324, the receiver of Lancashire was ordered to pay

Anthony Lucy a further £200 on top of the £100 he

had

already sent him to repair Carlisle castle's walls.

Simultaneously the sheriffs of Northumberland, Yorkshire and Lancashire

were ordered to send Lucy all the stone-cutters and masons they could

find ‘to do certain works of the king's there'.

The rebuilders seem to have done their job, for in April 1326 Carlisle

castle withstood being attacked by night, although the garrisons of the

city and castle were subsequently augmented by 20 sergeants and 60

foot. Two years later in 1328 the wars were ended with the

treaty

of Northampton and with this peace returned to the Scottish Marches for