Bothwell Castle

Bothwell is a large thirteenth century enclosure castle set on a high, steep

bank, above a bend in the River Clyde in South Lanarkshire. The

original castle is somewhat similar in design to Kildrummy, Dirleton

and Coull, having a round keep and D or circular-shaped smaller

towers. This fortress is again said to be based upon Coucy

castle, north-east of Paris.

History

History

The barony of Bothwell was created before 1159, but by which Scottish king is uncertain. There was once a charter by King Malcolm IV (1153-65) which granted David Olifant the land between the two river Calders (inter duas Caledouris) in exchange for his hereditary lands at Sawtry in Huntingdonshire. David is also said to have received lands from King David I

(1124-53) in Roxburghshire. From David these lands had passed to

Walter Moray by the mid thirteenth century, apparently through an

unnamed Olifant heiress. Bothwell castle, as the caput of this

barony, was

almost certainly in existence by 25 February 1279 when Walter Moray of

Bothwell, the probable husband of this unnamed Olifant woman, witnessed

a charter at Botheuyle

concerning lands he had inherited from the Olifants. Walter died

soon afterwards and the 13th century tombstone engraved with the Moray

arms within the church is probably his. By 1284 his son, William,

was described as pantler or steward of the Scots (panetarius de Scotiae).

On 17 July 1291, Andrew Moray swore fealty to King Edward I as overlord of

Scotland at Dunfermline cathedral chapter house. On 1 August it

was the turn of his elder brother of Bothwell, William Moray ‘the

Rich', to do likewise at Berwick. Both were members of the

auditors who scrutinised the claims of Bruce, Balliol, Comyn and all

the other competitors for the Crown of Scotland. After choosing

Balliol as king, William led 12 Morays, 6 of them being knights,

to do homage to King Edward I in 1292. Afterwards, as relations

deteriorated between Edward and certain elements of the Scottish

nobility, the bulk of the Scottish nobles generally reneged on their

oaths and made a treaty with France against King Edward. Edward

rapidly moved an army against these men. At the resultant battle

of Dunbar in April 1296, the Moray family seem to have fought en masse

and most were captured there when the castle surrendered. Amongst

the garrison were three earls, three barons, three bannerets and 28

knights. Lord William Moray of Bothwell (Botheville),

known as ‘the Rich', seems to have escaped the mass capture, but

later, on 28 August 1296, he was one of a multitude of barons who

renounced the French treaty and resumed their homage to King Edward.

William's younger brother, Andrew Moray Senior, was sent to the Tower

of London where he died on 8 April 1298, but his son, Andrew Moray

Junior, was sent to Chester, from where he soon returned to Scotland

and fomented rebellion in Moray before July 1297. This included

an abortive siege of Urquhart castle.

Despite this, he was granted permission in August to visit his father

in the Tower of London. Meanwhile William had died in poverty in

England during November 1300, stripped of his great estates. All

that remained to him were 2 lands around Berwick worth 10 marks

(£6 13s 4d) and 20 marks (£13 6s 8d) respectively and an

extra £2 if they were properly restored to their pre-war

standard. The jurors also found that his heir was his great

nephew, the 2 year old Andrew, grandson of William's brother, Andrew.

Before this, with the senior male members of the Moray family

incarcerated, the forces of King Edward I seized Bothwell castle in

1296, probably without any resistence. Andrew Moray Junior

returned from London, if he went, and apparently died of wounds soon

after the battle of Stirling Bridge on 11 September 1297.

Bothwell castle was meanwhile given to Aymer Valence, the earl of

Pembroke. Valence had obviously lost the castle by 23 September

1299, for that day the king arranged the release of his liege, James

Lindsay, lately taken prisoner by the Scots and held in Bothwell.

Although the castle was not mentioned as such, it seems unlikely that

he was held anywhere else. We also know that the castle changed

hands before 1307 as there is an undated document to Edward I from

Stephen Brampton, late warden of Bothwell castle, ‘which he

defended against the power of Scotland for a year and 9 weeks to his

great loss and misfortune as all his companions died in the castle

except for himself and those with him who were taken by famine and by

assault and moreover he was kept in hard prison in Scotland for 3 years

to the abasement of his estate'. The king ordered his being found

either a wardship or a marriage to help in his pitiable condition.

On 30 October 1300, the king ordered Aymer to provide Selkirk and

Bothwell castles ‘with men and victuals and to see that the

castellans of these places attack the enemy with all their force and

make no truce under pain of forfeiture to the king'. Despite this

it would appear that the castle fell again soon afterwards, or the

castellan appointed by Pembroke changed sides, for in 1301 the king had

to personally take Bothwell castle during that year's campaign.

To do this he brought a force of some 6,800 men and specially

constructed siege engines into Scotland. The troops consisted of

20 crossbowmen, 20 masons and 20 miners, the last two being led by a

logeman. A body of 20 men was attached to the king's person,

probably as a bodyguard, while the following counties contributed men;

Hereford 350, Worcester 340, Shropshire 546, Stafford 346, Derby 234,

Nottingham 250, Gloucester 225, unnamed counties (S English ones?) 507,

York 1,193, Northumberland 2019, the liberty of the abbot of Byland 15,

Berwick garrison 110, Roxburgh and Jedburgh garrisons 100 archers and

32 forest hobelars, Redesdale 200 archers from the earl of Angus, 264

archers from Tynedale, Edinburgh garrison 20 archers, 10 Selkirk

foresters and 61 archers from Knaresborough forest. During the

siege, on 10 August 1301, King Edward issued a charter stating what had

happened concerning Bothwell over the past 5 years. He declared

that on 10 July 1296, when William Moray surrendered to him at

Montrose, the king had taken his forfeited castle and barony of

Bothwell, worth £1,000 per annum, and granted it to Earl Aymer

Valence of Pembroke with all the land of the rebels who had held of

William. It is informative that there is no written document or

record of this transaction.

When the 1301 siege was concluded, the king handed the castle and its

lands back to Aymer. During the siege a belfry was built at

Glasgow and taken by land to the siege where it was used against the

fortress on a corduroy road built up to the castle. This trip of

7 miles from Glasgow took 2 days. The assault led to Bothwell's

surrender by 24 September 1301 and the army itself seems to have been

disbanded at Dunipace on 29 September. The belfry was then

dragged up to Stirling, but no siege occurred there, as, on 26 January

1302, the king agreed, due to French pressure, to make a truce with the

guardians of Scotland to last until November. English royal

records show royal garrisons were maintained at Berwick, Roxburgh,

Jedburgh, Selkirk, Peebles, Lanark, Carstairs, Edinburgh, Linlithgow,

Kirkintilloch, Ayr, Dalswinton, Dumfries and Lochmaben. Meanwhile

Aymer Valence had placed 16 serjeants into Bothwell castle under the

command of Nicholas Carew. A little later this force had been

increased to 30 serjeants, of whom 13 were now the king's. On 13

May 1306, King Edward's treasurer of Scotland wrote a letter from

Bothwell, while Botel [could have been Buittle] was still holding on 25 June 1311. In the

following year it was recorded that Walter Fitz Gilbert was custodian

of the castle and received 1s a day wages. The garrison consisted

of John Moray, Leionis Fitz Gilbert, John Marshall, Alan De Lisle, John

Fleming, William Fleming, Nigel Dounlopy and Nigel his son, Ralph

Cambron, Adam Cambron, William Cambron, Walter Eskyn, Patrick Fitz

John, Roger Wyther, Peter Knokkes, Robert Crok, Coleman le Marshall,

David Laundon, John de la More, Thomas Marshall, William del Spense,

Simon Fitz Annabel, Duncan Senewaghre, William Bonkhulle, Fynlawy

Donnouen, Nichals le Taillour, Hugh Fitz Elias and William Fitz Fergus,

scutifers at 1s a day. There was also Adam Fayrey, William

Castle, Alexander Kenny, John Steel, Alan Danielstone, John

Colemaneson, William de Lisle, Reginald Wode, John Longe, Hugh Twedyn,

William Fourbour, Adam Fitz Hugh, Henry Fitz Robert, Robert le

Taillour, Brice de la More, Patrick Fitz Arnold, Richard Fitz Agnes,

Adam Fitz Agnes, Maymund, William Corveyser, Scot Lorimer, Edgar

Inverkip, Thomas Brandon, alan Laberok, Thomas Fitz Alan, Patrick Fitz

Alan, Alan Fitz Stephen, Alexander Redheuid, Geoffrey Lange and Robert

Little, archers, paid at 2d per day from 8 July for 7 days and for 365

days because of the leap year.

On 12 December 1311, King Edward II ordered Walter Fitz Gilbert,

‘who the king had placed in command of the fortress lest it fell

into the hands of the enemy through want of munitions', to restore the

castle to the earl of Pembroke and answer to him as he did before

Edward took this action. The castle may have fallen soon

afterwards for it was last mentioned on 8 February 1312 when Edward II

ordered Walter to ensure that the castle ‘is safely and securely

kept and delivered to no other person whatsoever without the king's

letters patent under the great seal of England directed to

himself'. Such a direction would suggest that the castle garrison

was in considerable difficulties. Sure enough the late fourteenth century ‘historian' Fordun notes the fall of Buth

castle in 1312. This is certainly more believable than the

fantasist Barbour's statement that the castle, after Bannockburn in

1314, offered shelter for the earl of Hereford and 50 of his men who

were then tricked into staying in unsuitable lodgings and handed over

to Robert the Bruce. Conversely the Lanercost chronicler is more

likely accurate when he states that the earl was captured on the road (in via apud castrum de Bothevil)

and then imprisoned in the castle by the custodian who had formerly

held the castle for King Edward. The violently pro-Edwardian

chronicler then accused the constable of bad faith in holding the earl

and his men within the castle and handing them over to Bruce. He

later wrote of Botevile castle ‘which the Scots had formerly

destroyed and abandoned' by September 1336. Most likely this

destruction happened in 1314 soon after Bannockburn as the castle was

obviously still functional and in Scots hands in the June of that year.

On 20 July 1327, Andrew Moray was described in a charter of King Robert Bruce as the steward of the Scots (panetarius Scotiae),

so obviously he had inherited his great uncle's office was well as his

Bothwell estate - even though the castle probably remained a

ruin. This occurred a year after he had taken Christiana, King

Robert's twice widowed sister, to wife. As she was probably in

her late 30s or early 40s at the time there is no reason to follow

‘received wisdom' and invent an earlier wife for Andrew to be the

father of his two known children, John and Thomas.

After the battle of Dupplin Moor in August 1332, Andrew was chosen

regent, but he was captured the next year at Roxburgh castle. He

was ransomed in 1335 and by December was acknowledged as guardian of

Scotland. About 18 October 1336, King Edward III marched through

Scotland intent on a winter campaign to conquer the land. His

army stopped at Bothwell between at least 18 November and 16 December

1336 and the locals, being unable to oppose him, submitted to him

through fear rather than love and he repaired the castle and left a

garrison there under Walter Selby. Works at the fortress were

entrusted to John Kilburne who also had the rebuilding of Edinburgh castle

in his care. For his expertise he received 1s a day. The

following year, after 2 February, Andrew Murray (d.1338), the great-nephew of

William the Rich, knowing that the king of England and his men had

retired to ‘distant parts', besieged St Andrews castle and afterwards the newly garrisoned Bothwell castle

and ‘because Earl Robert Ufford of Suffolk, to whom as well as to

the warden, that castle had been committed by the king, was absent at

the time, the castle quickly surrendered to the Scots upon

terms'. The terms were that they should retire with their limbs

and all possessions safely to England. The later chronicler

Wyntoun speaks of the castle being attacked with a wooden belfry called

Bowstower and Stephen Wiseman being half-slain there, before William

Willeris withdrew the garrison back to England. At this point the

castle was ‘scattered from its foundations'. In contrast,

the more reliable Fordun speaks of the storming of ‘the tower of

Bothwell' which occurred ‘not without loss to his own men' as

Stephen Wisman was killed there. This description of the tower of

Bothwell strongly suggests that the outer parts of the castle were not occupied by the time of the siege of 1337.

Following his victory Moray slighted his own castle and marched on

Stirling castle before 29 May. After this apparently

whole-hearted destruction of the castle it remained derelict until the

1360s. Andrew died in 1338 after an abortive siege of Edinburgh

castle. He was only 40. His widow lived on until 1357 when

she was at least 67. Their two sons both died relatively young,

John as a hostage in England in 1351 and Thomas in 1361 also in England

as a hostage for his king.

At this point the Morays were dispossessed of Bothwell. On 23

July 1362, Archibald Douglas ‘the Grim' was granted a papal

dispensation to marry Joanna the widow of Thomas Moray of

Bothwell. With her hand Archibald took possession of Bothwell,

even though there were still other Morays who could have claimed the

fortress and barony. Archibald later became lord of Galloway and

earl of Douglas. His nickname was allegedly given to him by the

English ‘because of his terrible countenance in warfare'.

He commenced rebuilding Bothwell, repairing the keep with a crosswall

and building a new enceinte. At the same time he is said to have

built the great rectangular tower keep at Threave in Galloway which

does bear comparison with works at Bothwell keep. Archibald also

constructed the collegiate church of Bothwell in 1398 and married his

daughter to the duke of Rothesay there in 1399. The work at

Bothwell castle was apparently continued by his son, Archibald, the 4th

earl. By his death at the battle of Verneuil in 1424, he and his

father had constructed a great hall and adjacent chapel, with towers at

the north-east and south-east corners, and curtain walls connecting them to the keep,

enclosing the courtyard at Bothwell.

The "Black" Douglases forfeited their lands in 1455 and the castle

returned to the Crown. King James III granted Bothwell to Lord

Crichton, and then to Sir John Ramsay. They both had their lands

forfeited in turn. In 1488 Bothwell was granted to Patrick

Hepburn, who was made earl of Bothwell. Hepburn exchanged the

castle with Archibald "Bell-the-Cat" Douglas, fifth earl of Angus, in

return for Hermitage castle in Liddesdale. James IV visited

Bothwell in both 1503 and 1504. In 1584 the countess of Angus was

living in the castle when she was ordered to surrender it due to the

treason of her son. It had been returned by 1594 when it was

recorded with disapproval that Catholic mass was being performed

there. By this time the castle must have been getting rather long

in the tooth, but it was not until the time of Archibald Douglas, first

earl of Forfar (1653-1712), that construction began of a new mansion

nearby, apparently demolishing parts of the castle for its stone.

His house in turn was demolished in 1926 due to mining subsidence in

the area.

Description

Description

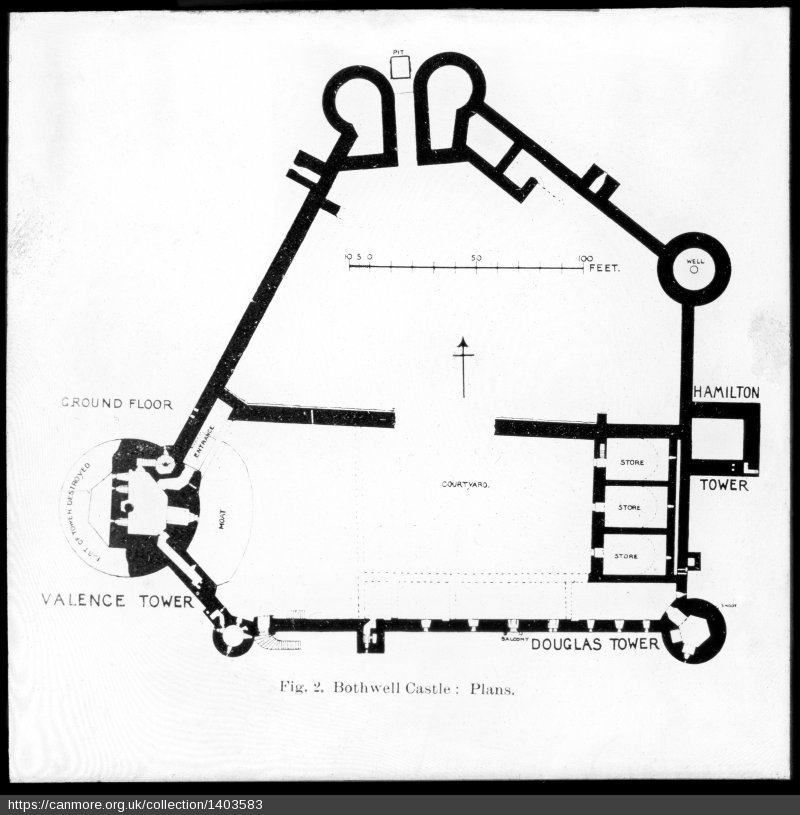

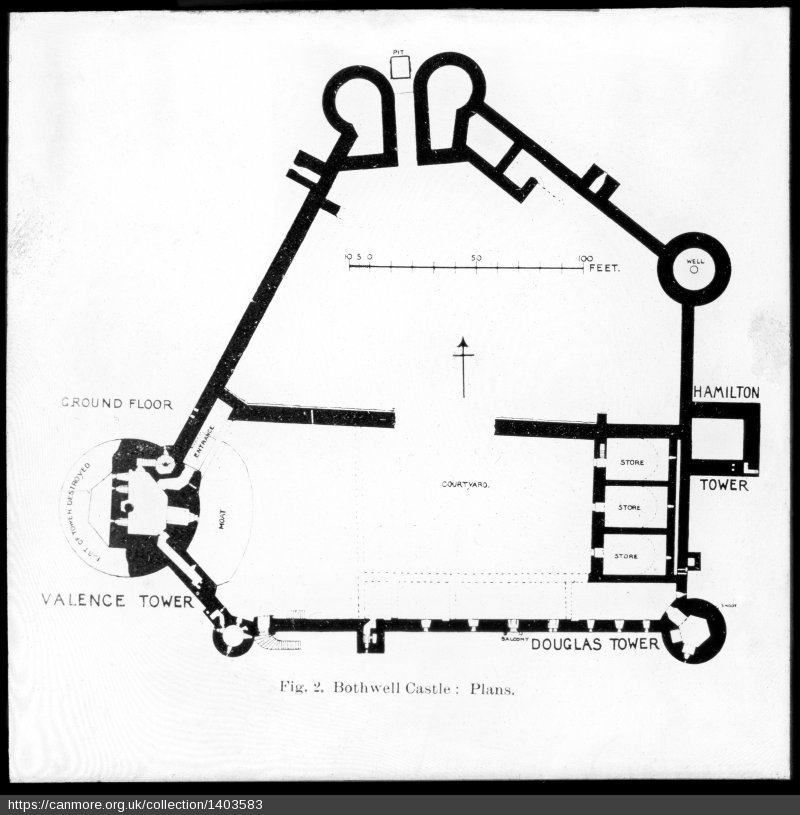

Thankfully the archaeological history of Bothwell castle can be told

after a thorough excavation by the old Office of Works. This

showed conclusively that the outer parts of the castle, including the

great twin-towered gatehouse, north-east round tower (which contained a well

only 8' deep. In the fifteenth century

this was partially filled in with canon balls!) and 2 rectangular

turrets were never built beyond a few courses. Further, the

enjoining curtains were never even started and not even a foundation

trench was dug. As such Bothwell was a failed fortress, which

only became anything like complete in the late fourteenth century.

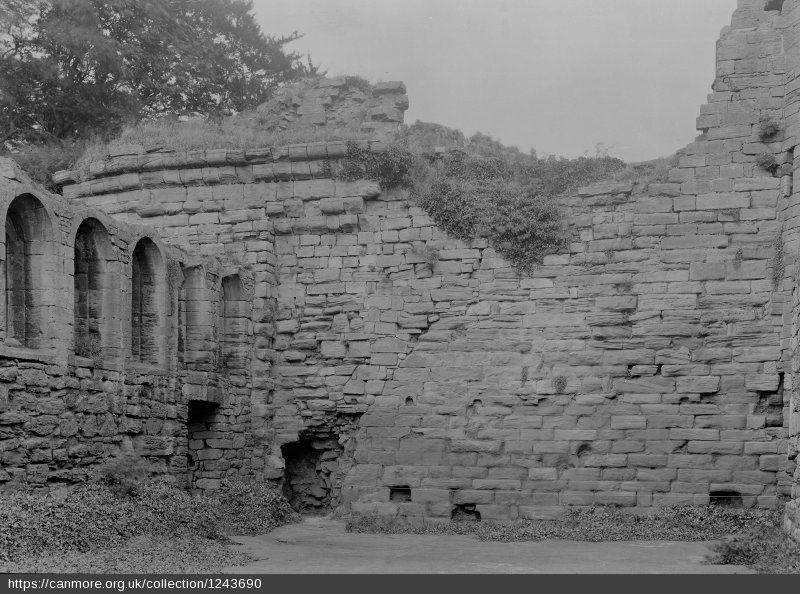

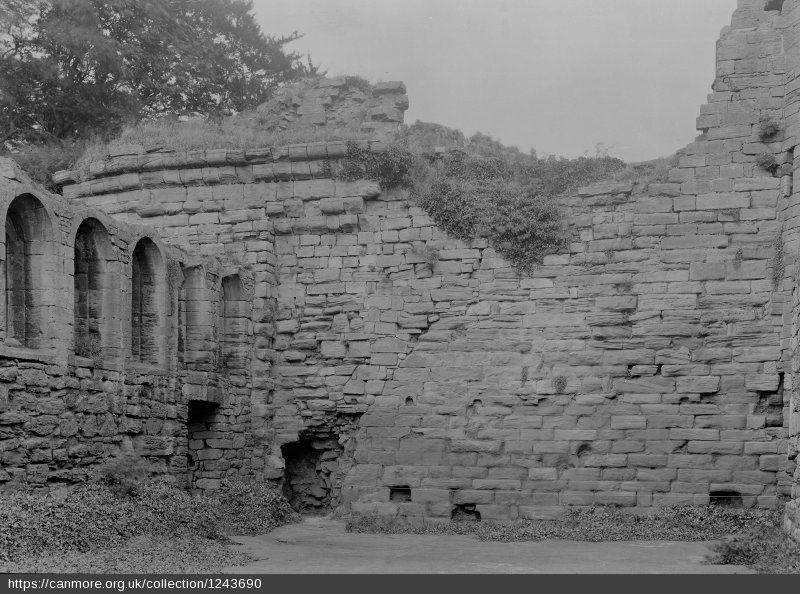

The heart of the present ruins of Bothwell castle is its round keep

which is built of a notably superior ashlar masonry. This, on its

internal side, was originally protected by a wet moat, 25' wide and 15'

deep. It still retains a sluice to the south. This was so

positioned that when opened it flushed out the waste from the

garderobes overhanging the exterior of the enceinte. The tower

was of 4 storeys, being 82' high and 62' in diameter with walls 15'

thick. It was entered via a drawbridge and portcullis via a

projecting beak into a chamber on the inside of the west curtain.

This led to a polygonal chamber of which only a little less than half

now remains. From here a spiral stair was set in a bulge against

the west curtain, while originally a central pillar held up the stone roof

of the tower vaults. The stair gave access to the higher floors

as well as the basement where there was a well some 20' deep.

Note the machicolations over the entrance doorway on the summit of the

tower. After the keep's partial destruction in 1337 a crosswall

was inserted to make the structure habitable again. The round

arched, unmoulded window embrasures here are similar to those found at

Threave castle and both are therefore reckoned to be the work of

Archibald the Grim who died in 1400.

To the north of the keep the curtain was 12' thick including the chambers

making up the keep entrance approach. The southernmost chamber of

this led to a postern with portcullis, yett and door, tight under the

keep walls, although how the room was accessed is problematical.

This is somewhat similar to the design of Dirleton.

The bulk of this wall above the lower part of the postern is a later

rebuild, with a sharp join between it and the older wall of the

keep. From the keep the south-west curtain wall, 10' thick, contained a

mural passageway at this first floor level as well as the level

above. These both led off towards twin latrine chutes and the

much smaller south-west tower (20' diameter with walls 6' thick). This

too was of 4 storeys, the lower 2 being circular and the upper ones

polygonal. Next to the tower was a small internally projecting

rectangular postern covered by a long crossbow loop in the adjoining south-west

tower. All of this work pre-dates 1296, although high above the

postern on the wallwalk machicolations are the Douglas coat of arms -

which could only have been added after 1362 when Archibald took over

the fortress. The gateway itself, protected by a portcullis and a

gate, was shoulder headed - a fashion typical from 1250 to 1350.

At this point there is a clear break in wall style as the 6' thick

curtain continues down the S face of the enceinte set upon a scarped

projection of bedrock overlooking the River Clyde.

East

of the postern is a large rectangular latrine turret which descends to

the base of the uneven bedrock and would appear to be fourteenth century.

This has lost its upper floors, but, like the curtain wallwalk, was

serviced by a spiral stair, unusually built within the curtain

itself. Along the inside of this south front lay a long range of

buildings of the post 1362 castle. These were serviced by the

rectangular latrine turret. All these buildings are gone apart

from their traces fossilised in the curtain wall. Not even

excavation uncovered their interior walls as the floor and foundations

had been totally grubbed up and the ground cut away. The upper

section, with fine windows, set in a thin wall would appear to be

sixteenth century. The junction between the two works is readily

apparent on the

inside, though not so pronounced externally. This suggests the

whole front has been refaced. At the east end was a chapel which

abutted against the boldly projecting south-east tower. Two of the

trefoil chapel windows have been truncated by the new upper work when a

balcony was added on this front to give a vista down the Clyde.

It is also apparent that the much modified wallwalk on the south front

never ran all the way to the south-east tower, but stopped at the chapel - or

it certainly did in the final phase we have evidence for. The

chapel roof creasing on the side of the tower also suggests that the

wallwalk never reached this far.

East

of the postern is a large rectangular latrine turret which descends to

the base of the uneven bedrock and would appear to be fourteenth century.

This has lost its upper floors, but, like the curtain wallwalk, was

serviced by a spiral stair, unusually built within the curtain

itself. Along the inside of this south front lay a long range of

buildings of the post 1362 castle. These were serviced by the

rectangular latrine turret. All these buildings are gone apart

from their traces fossilised in the curtain wall. Not even

excavation uncovered their interior walls as the floor and foundations

had been totally grubbed up and the ground cut away. The upper

section, with fine windows, set in a thin wall would appear to be

sixteenth century. The junction between the two works is readily

apparent on the

inside, though not so pronounced externally. This suggests the

whole front has been refaced. At the east end was a chapel which

abutted against the boldly projecting south-east tower. Two of the

trefoil chapel windows have been truncated by the new upper work when a

balcony was added on this front to give a vista down the Clyde.

It is also apparent that the much modified wallwalk on the south front

never ran all the way to the south-east tower, but stopped at the chapel - or

it certainly did in the final phase we have evidence for. The

chapel roof creasing on the side of the tower also suggests that the

wallwalk never reached this far.

The south-east tower, with walls up to 9' thick, consisted of 4 floors, with

the upper 3 being linked via a spiral stair to the north. First floor

entrance was apparently gained through the hall via a passageway in the

chapel east wall. Chapel and tower decoration are similar to that of

Lincluden college founded by Earl Archibald shortly before his death in

1400, but not finished until after 1409. As the south-east tower is

crowned with impressive machicolations which are very reminiscent of

French style, this portion of the ruins may therefore be the work of

Duke Douglas of Touraine before his death in 1424. Presumably the

tower lies upon thirteenth century

foundations as its 30' diameter is similar to those of the north-east tower

(34') and gatetowers (32'). Indeed, in the first floor, covering

the south curtain, is a long, unadorned crossbow loop of a type typical in

the thirteenth century. The rectangular windows all look of a later date.

Next to the chapel within the weak east curtain was a large hall.

This area of the castle has been much rebuilt. The east curtain

itself consists of a rubble built wall only 4' thick, but containing 2 ‘13th century'

loops set within narrow embrasures at the south end. As such it was

not defensible in medieval terms. This is usually stated to have

been the work of Archibald the Grim before 1400. This wall and

the north curtain wall, which is generally and probably wrongly thought of

as of a similar age, have been heightened some 5' in ashlar work at a

later date. The upper courses are made of rectangular blocks and

had a corbelled out wallwalk of typically fifteenth century Scottish style.

However, the bases and widths of the east and north curtain should be compared

and it then becomes obvious that they have different plinths and are

set at different levels. This mitigates against them being the

same age.

The

so-called hall was possibly originally free standing and is not

connected to the nearby east curtain as would be usual. Instead

there are 3 narrow loops pointing into the narrow passageway between

hall east wall and east curtain. The differing thicknesses of the hall

walls and repeated changes in style, plus the butt joints between the

walls, suggest that it is of at least 3 phases. The north wall, some

7' thick, is used as the north curtain wall and is on a slightly different

alignment to the rest of the north curtain, which is 8' thick and has a

much more elaborate plinth. The hall north wall contains a

shoulder-headed fireplace and has a simple stepped plinth unlike

anything at the rest of the castle. There are also the remains of

a spiral stair in the north-west corner, obviously replaced by the later stair

in the north section of the newer west wall. It is uncertain how this

work related to the earlier castle, but it is possible that this is the

earliest work on the site and dates back to the days of the Oliphants

(pre1242). The rest of the hall is traditionally dated as fifteenth century

and has 3 doorways leading into 3 basement vaults of an even later

date. Note that this west wall is not bonded onto the north and south walls

and therefore postdates them. Any earlier wall here must

therefore have been on another alignment, all trace of which has now

gone, or possibly it was of wood. On the summit of the west wall are

an impressive line of trefoil windows that were once all glazed as is

evidenced by the grooves for glass in their interior. Next to

this and possibly of an earlier date, is a traceried window with a

quatrefoil roundel at its summit. In style these could just be thirteenth century, but in situ they look fifteenth century

or later. Possibly they are reused from elsewhere or had an

anachronistic patron! These should be compared with the two

apparently thirteenth century

windows in the keep opposite. At the south-west corner of the hall it is

apparent that the south wall, only 4' thick, is butted onto by the

apparently later 6' thick west wall. The south wall also seems to have

been rebuilt from about 6' up. It should further be noted that

there is no fireplace in the ‘hall' - other than the early one in

the north wall which is set between current floors and that fireplaces are

otherwise a feature found in abundance elsewhere in the castle.

The

so-called hall was possibly originally free standing and is not

connected to the nearby east curtain as would be usual. Instead

there are 3 narrow loops pointing into the narrow passageway between

hall east wall and east curtain. The differing thicknesses of the hall

walls and repeated changes in style, plus the butt joints between the

walls, suggest that it is of at least 3 phases. The north wall, some

7' thick, is used as the north curtain wall and is on a slightly different

alignment to the rest of the north curtain, which is 8' thick and has a

much more elaborate plinth. The hall north wall contains a

shoulder-headed fireplace and has a simple stepped plinth unlike

anything at the rest of the castle. There are also the remains of

a spiral stair in the north-west corner, obviously replaced by the later stair

in the north section of the newer west wall. It is uncertain how this

work related to the earlier castle, but it is possible that this is the

earliest work on the site and dates back to the days of the Oliphants

(pre1242). The rest of the hall is traditionally dated as fifteenth century

and has 3 doorways leading into 3 basement vaults of an even later

date. Note that this west wall is not bonded onto the north and south walls

and therefore postdates them. Any earlier wall here must

therefore have been on another alignment, all trace of which has now

gone, or possibly it was of wood. On the summit of the west wall are

an impressive line of trefoil windows that were once all glazed as is

evidenced by the grooves for glass in their interior. Next to

this and possibly of an earlier date, is a traceried window with a

quatrefoil roundel at its summit. In style these could just be thirteenth century, but in situ they look fifteenth century

or later. Possibly they are reused from elsewhere or had an

anachronistic patron! These should be compared with the two

apparently thirteenth century

windows in the keep opposite. At the south-west corner of the hall it is

apparent that the south wall, only 4' thick, is butted onto by the

apparently later 6' thick west wall. The south wall also seems to have

been rebuilt from about 6' up. It should further be noted that

there is no fireplace in the ‘hall' - other than the early one in

the north wall which is set between current floors and that fireplaces are

otherwise a feature found in abundance elsewhere in the castle.

The original east curtain would have ended with the unbuilt north-east round

tower. However, at the corner of the current ward is the boldly

projecting east tower. This projects into the bottom of the

presumably thirteenth century

ditch, although the base of this curtain and tower are now covered with

soil. The square tower, now mostly destroyed, was an original

part of the castle as can be seen by the lowest six courses of fine

ashlar work which is similar to that found in the keep. After its

rebuilding in the fourteenth century

it was entered at second floor level via a French style drawbridge and

Romanesque arch. In this it mimics the early thirteenth century

entrance to the great keep. A spiral stair could then be reached

in the internal wall of the tower. The heavily fortified entrance

was abandoned when the present hall was built, which would suggest that

this workmanship dates to the time of Earl Archibald (1362-1400).

An internal garderobe arrangement in the south-east corner is also similar to

that found in the keep attributed to Archibald at Threave.

West of the hall, on the inner side of the roughly built, rubble curtain,

are the remains of the kitchen oven and fireplace and traces of another

stairway. A large rectangular gatetower stood in the gap in the

8' thick curtain, but this and the east tower were demolished for stone

when the new house was built in the eighteenth century

(they were still sanding in 1693). Both ends of this curtain were

topped by circular bartizans surmounting rectangular

buttresses. These were added with the top 6' of wall and

parapet in the fifteenth century, overlying the earlier wall and plain

wallwalk. Here and there in the curtain wall are pieces of reused

apparently thirteenth century

ashlar which shows that this wall was built after the first castle was

demolished. This gives quite a firm chronological dating for the

wall of post 1337 and pre fifteenth century.

It therefore appears to be the work of Earl Archibald (d.1400).

Such an opinion is bolstered by the cruciform loop in the chamfered off

angle at the west end of the wall. This has deeply splayed

fish-tailed oillets of a form that should not predate 1350. The

loop is set in the north chamber of the suite of rooms entered to approach

the keep and is quite different to the longer cruciform loop of the south-west

wallwalk in the keep which is probably late thirteenth century.

In 1710 the castle towers were recorded as Valence, Douglas, Hamilton,

Cumming and Dungeon. Probably the keep was the donjon or dungeon,

and therefore the other towers may be named in reverse order from it,

with the Cumming tower being the round tower now called the prison

tower, the Latrine turret being Hamilton, the south-east tower Douglas and the

rectangular tower the Valence tower. If this is correct it would

suggest that the rectangular tower is older (c.1301-12) than the corner

tower which dates to the late fifteenth century.

Such designations from 1710 in any case are unreliable and could easily

refer to a different order. As such, they should be regarded with

much caution.

Why not join me at Bothwell and other Great Scottish Castles this Spring? Information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2016

Paul Martin Remfry

History

History History

History Description

Description East

of the postern is a large rectangular latrine turret which descends to

the base of the uneven bedrock and would appear to be fourteenth century.

This has lost its upper floors, but, like the curtain wallwalk, was

serviced by a spiral stair, unusually built within the curtain

itself. Along the inside of this south front lay a long range of

buildings of the post 1362 castle. These were serviced by the

rectangular latrine turret. All these buildings are gone apart

from their traces fossilised in the curtain wall. Not even

excavation uncovered their interior walls as the floor and foundations

had been totally grubbed up and the ground cut away. The upper

section, with fine windows, set in a thin wall would appear to be

sixteenth century. The junction between the two works is readily

apparent on the

inside, though not so pronounced externally. This suggests the

whole front has been refaced. At the east end was a chapel which

abutted against the boldly projecting south-east tower. Two of the

trefoil chapel windows have been truncated by the new upper work when a

balcony was added on this front to give a vista down the Clyde.

It is also apparent that the much modified wallwalk on the south front

never ran all the way to the south-east tower, but stopped at the chapel - or

it certainly did in the final phase we have evidence for. The

chapel roof creasing on the side of the tower also suggests that the

wallwalk never reached this far.

East

of the postern is a large rectangular latrine turret which descends to

the base of the uneven bedrock and would appear to be fourteenth century.

This has lost its upper floors, but, like the curtain wallwalk, was

serviced by a spiral stair, unusually built within the curtain

itself. Along the inside of this south front lay a long range of

buildings of the post 1362 castle. These were serviced by the

rectangular latrine turret. All these buildings are gone apart

from their traces fossilised in the curtain wall. Not even

excavation uncovered their interior walls as the floor and foundations

had been totally grubbed up and the ground cut away. The upper

section, with fine windows, set in a thin wall would appear to be

sixteenth century. The junction between the two works is readily

apparent on the

inside, though not so pronounced externally. This suggests the

whole front has been refaced. At the east end was a chapel which

abutted against the boldly projecting south-east tower. Two of the

trefoil chapel windows have been truncated by the new upper work when a

balcony was added on this front to give a vista down the Clyde.

It is also apparent that the much modified wallwalk on the south front

never ran all the way to the south-east tower, but stopped at the chapel - or

it certainly did in the final phase we have evidence for. The

chapel roof creasing on the side of the tower also suggests that the

wallwalk never reached this far. The

so-called hall was possibly originally free standing and is not

connected to the nearby east curtain as would be usual. Instead

there are 3 narrow loops pointing into the narrow passageway between

hall east wall and east curtain. The differing thicknesses of the hall

walls and repeated changes in style, plus the butt joints between the

walls, suggest that it is of at least 3 phases. The north wall, some

7' thick, is used as the north curtain wall and is on a slightly different

alignment to the rest of the north curtain, which is 8' thick and has a

much more elaborate plinth. The hall north wall contains a

shoulder-headed fireplace and has a simple stepped plinth unlike

anything at the rest of the castle. There are also the remains of

a spiral stair in the north-west corner, obviously replaced by the later stair

in the north section of the newer west wall. It is uncertain how this

work related to the earlier castle, but it is possible that this is the

earliest work on the site and dates back to the days of the Oliphants

(pre1242). The rest of the hall is traditionally dated as fifteenth century

and has 3 doorways leading into 3 basement vaults of an even later

date. Note that this west wall is not bonded onto the north and south walls

and therefore postdates them. Any earlier wall here must

therefore have been on another alignment, all trace of which has now

gone, or possibly it was of wood. On the summit of the west wall are

an impressive line of trefoil windows that were once all glazed as is

evidenced by the grooves for glass in their interior. Next to

this and possibly of an earlier date, is a traceried window with a

quatrefoil roundel at its summit. In style these could just be thirteenth century, but in situ they look fifteenth century

or later. Possibly they are reused from elsewhere or had an

anachronistic patron! These should be compared with the two

apparently thirteenth century

windows in the keep opposite. At the south-west corner of the hall it is

apparent that the south wall, only 4' thick, is butted onto by the

apparently later 6' thick west wall. The south wall also seems to have

been rebuilt from about 6' up. It should further be noted that

there is no fireplace in the ‘hall' - other than the early one in

the north wall which is set between current floors and that fireplaces are

otherwise a feature found in abundance elsewhere in the castle.

The

so-called hall was possibly originally free standing and is not

connected to the nearby east curtain as would be usual. Instead

there are 3 narrow loops pointing into the narrow passageway between

hall east wall and east curtain. The differing thicknesses of the hall

walls and repeated changes in style, plus the butt joints between the

walls, suggest that it is of at least 3 phases. The north wall, some

7' thick, is used as the north curtain wall and is on a slightly different

alignment to the rest of the north curtain, which is 8' thick and has a

much more elaborate plinth. The hall north wall contains a

shoulder-headed fireplace and has a simple stepped plinth unlike

anything at the rest of the castle. There are also the remains of

a spiral stair in the north-west corner, obviously replaced by the later stair

in the north section of the newer west wall. It is uncertain how this

work related to the earlier castle, but it is possible that this is the

earliest work on the site and dates back to the days of the Oliphants

(pre1242). The rest of the hall is traditionally dated as fifteenth century

and has 3 doorways leading into 3 basement vaults of an even later

date. Note that this west wall is not bonded onto the north and south walls

and therefore postdates them. Any earlier wall here must

therefore have been on another alignment, all trace of which has now

gone, or possibly it was of wood. On the summit of the west wall are

an impressive line of trefoil windows that were once all glazed as is

evidenced by the grooves for glass in their interior. Next to

this and possibly of an earlier date, is a traceried window with a

quatrefoil roundel at its summit. In style these could just be thirteenth century, but in situ they look fifteenth century

or later. Possibly they are reused from elsewhere or had an

anachronistic patron! These should be compared with the two

apparently thirteenth century

windows in the keep opposite. At the south-west corner of the hall it is

apparent that the south wall, only 4' thick, is butted onto by the

apparently later 6' thick west wall. The south wall also seems to have

been rebuilt from about 6' up. It should further be noted that

there is no fireplace in the ‘hall' - other than the early one in

the north wall which is set between current floors and that fireplaces are

otherwise a feature found in abundance elsewhere in the castle.