The North Curtain Wall of

the Outer Ward

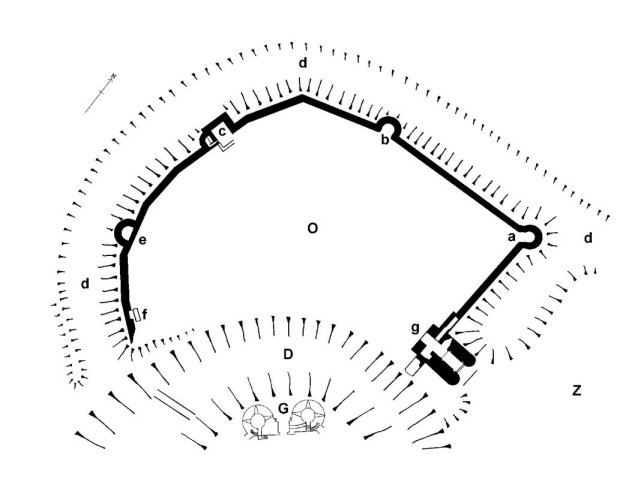

At the end of the mostly collapsed east curtain wall was a backless

circular mural tower (a) of two storeys. This is about 20' in external diameter. The tower is joined to the curtain

on the west side by a short section of wall which is obviously part of

the original plan. Probably it indicates that the architects

did not plan the wall and tower properly with the result that there was

a gap of several feet between them which had to be filled with this

little section of wall. Externally a sloping plinth is still

evident around the tower. Such plinths are lacking on the

outer ward curtain wall. Apparently this is because the walls

stand on top of the bank of the outer ditch (d), while the towers

protrude down the slope into the ditch. On the ground level

of the corner tower is yet another 'blind' room. Above is a

room with three crossbow loops. This is the standard layout

in the outer ward towers, a reversal of what is seen in the inner ward

both at White Castle and Dover castle, but similar to the Skenfrith

towers. There appears to be no doorway into the ground floor,

or the floor above. There is merely an aperture, which may

once have been blocked with a wooden wall similar to that of a

‘black and white house'.

On the first floor are three staggered

cross loops set in wide embrasures. These have angular roofs

and are quite shallow, due to the thinness of the walls.

Externally the embrasures supported three similar split sighted

crossbow loops with ball top and bottom oillets. This layout,

apart from the open back, is reminiscent of the towers at Skenfrith

castle. Indeed the embrasures with their pointed segmental

arches, three to a floor above a basement, are pure

Skenfrith. It is uncertain how access was gained to the upper

floor. Possibly it was via wooden steps to the rear, or even

a wooden stair down from the wallwalk at second floor level.

It is interesting that the ground floor would have been left literally

undefended by crossbow fire. This is the opposite to the

inner ward at White Castle.

Two-thirds of the way along the north

curtain stands a half round tower (b), otherwise similar in design to

its corner companion to the east (a). This is the most ruined

of the towers of the outer ward. The bulk of its first floor

loops have been stripped from their embrasures and looking into this

tower you could be forgiven for mistaking it for one of those at

Skenfrith. Within the tower the ball base oillets of the

north and west loops are still in situ showing that the tower

originally had similar loops to the others. The rear wall of

this tower has been gouged out at ground level and the basement walls

robbed of their facing. The upper floor, however, is

externally perfect at the rear and this shows that the tower was either

open to the air or wooden backed. Although the top of the

tower is now gone, it presumably had a fighting platform similar to the

other towers at the castle.

From the north tower (b) the curtain

makes three irregular sweeps, leaving a vulnerable unflanked angle,

round to the largest tower in the outer enceinte (c). The

unflanked angle is not buttressed with quoins, unlike the south-east

wall of the inner ward. Presumably this suggests that the

south-east curtain post-dates the outer ward (O). There is a

similar unflanked angle as this at Wigmore

castle which was probably

built in the early to mid-thirteenth century. There are no

features in the rest of the outer ward curtain that differ

significantly from the rest of the structure in style or date.

Costings, Comparisons and

Conclusions

It is worthwhile here reciting a few figures concerning castle building

during the reign of King Henry III (1216-72) to strengthen the opinion

that Hubert Burgh built the White Castle we know today.

Firstly the king is recorded as spending about £85,000 on

castle works, an annual expenditure of some £1,500.

Henry's largest expenses in Wales were Montgomery

castle at some

£2,000 between 1222 and 1226 and Dyserth and Degannwy, which

could not have cost less than £7,500 between them.

Other than the minuscule amounts recorded in the history of the castle

above, no serious royal building works are recorded as being undertaken

at White Castle for the Crown. As will be seen below, the

building of the six towers and outer ward would probably have cost some

£2,600 in the mid-thirteenth century; we can therefore

presume that it was the immensely rich Earl Hubert Burgh of Kent who

was responsible for the refortification of White Castle, and not the

impecunious Lord Edward. The style of the castle probably

rules out its later rebuilding by Edward's far richer brother, Prince

Edmund Plantagenet (1245-96) when he held the castle after 1267.

To give an idea of the cost of building

something like the later portions of White Castle we will examine some

of the building works of King Edward I (1272-1307) during his conquest

of Wales. In May 1277 at Builth

Wells castle it cost

£5 to assemble and roof a set of timber buildings which were

to serve as chapel, hall, chamber, kitchen and smithy to the new

castle. By mid-November all these buildings had been

dismantled (avulse)

and replaced by a new great hall, kitchen,

brewhouse and stable. Also in May nineteen carpenters were

sent to Builth from Abergavenny ‘to build a certain tower

there'. They were assisted by 28 men with picks and shovels

and by November had built enough to require this structure, the

brattishing, and two rooms to be covered in straw as a protection

against the frost. By 13 January 1278 over £218 had

been spent on the wages of masons and quarrymen and over £85

on carpenters. From November to May only some twelve

shillings was spent on digging and bringing stone from the quarries to

the castle. Then, from 18 April, costs increased, rising from

nearly £4 to £7 3s 10d in May, where it remained

until mid-September, before dropping again during the winter

doldrums. At the end of April 1278 expenses began to rise

again and throughout the year lead was shipped in from Shelve in

Shropshire and cast

and laid by a master plumber. This must

surely indicate the roofing of finished buildings.

Interestingly the sum of £16 6s 8d was expended in making a

great palisade, 49 perches (808½') long, round the outer

bailey. The distance quoted would suggest that this wall was

not to surround just the outer bailey, which has a circumference of

only 500', but the entire castle, the outer earthwork surrounding

it being some 1,000' long. Alternatively the

circumference of the inner ward is about 800'. Probably

only excavation could elucidate on this point.

At Builth it was intended to remove the

49 perch long palisade and in April 1280 the constable of the castle

was ordered to send the best of the brattishing from it to Roger

Mortimer as the king's gift. However by October 1280 the

masonry wall to replace it had only just been begun across the ditch to

the outer ward. The rest of the apparently completed castle

consisted of a great tower, a stone wall with six turrets (turriculis)

surrounding the castle, a turning bridge with two great towers (magnis

turrellis), a stone wall near this bridge and enclosing

the inner

bailey and a ditch around the bailey, which was partially filled at one

point by the paltry attempt to enclose the outer bailey. Work

continued at a diminishing tempo until September 1282, but was never

completed. The surviving accounts suggest that about forty

masons and around 130 workmen, of whom some 35 were women at 6d instead

of 7d a day, made up the workforce during the summer. In

total £1,666 9s 5¼d had been spent over the five

years. In 1343 it was found that a further £200

would have been necessary to complete the great gatehouse which had

been left unfinished in 1282.

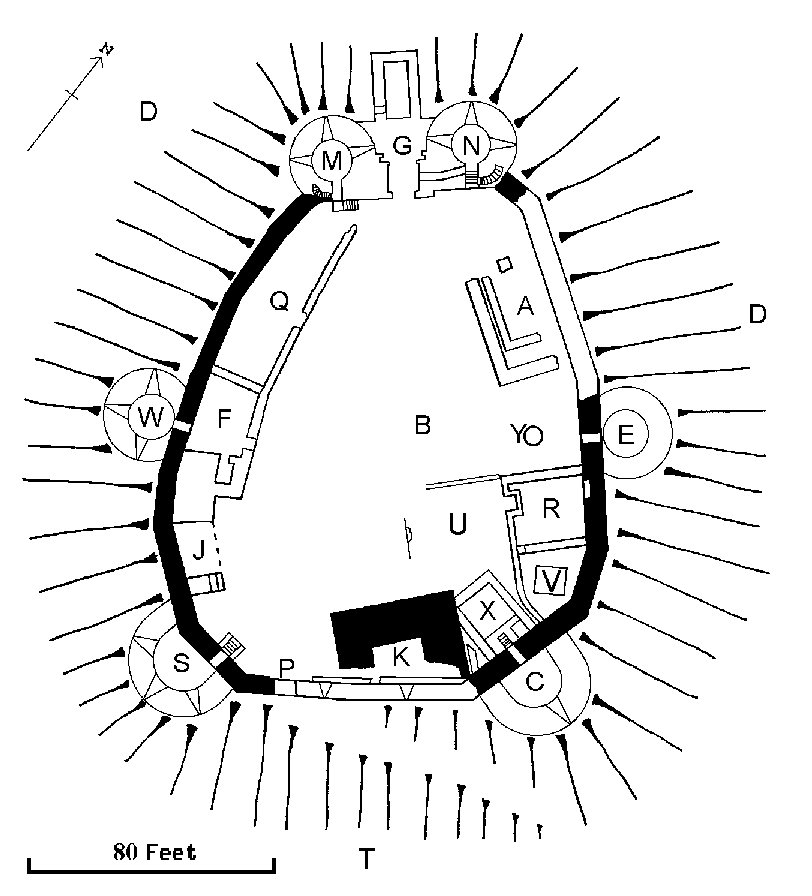

At White Castle the outer bailey (O) has

a circumference of roughly 850', so it is a great pity that the

Builth wall was never completed or costed as this would have been a

good comparison. The circumference of the twelfth century

inner ward (B) wall is about 500' and cost at least £131

2s 8d between 1185 and 1186. Interestingly, at Aberystwyth

castle in 1286, making fifty perches (825') of what was

apparently

half the outer castle wall to the north cost only £37 10s

10d. This seems a very low sum and probably relates to the

‘third bailey' which had been largely destroyed by the sea by

1343 and of which no trace is currently visible.

At Conway castle we still have the

payments made for the construction of the south wall of the

town. Five D shaped, open backed turrets, each about 28'

high, were charged at sixteen shillings per foot built.

Further costs were £12 10s for battlementing the towers and

£1 5s 10d for rendering the battlements. This

suggests that the rest of the walls remained exposed and

un-limed. The roughly 1,000' of curtain walling between

the towers, 16' 4" high, cost

£117. Finally the twin D towered Mill gatehouse,

which was far more advanced than the outer gatehouse (g) at White

Castle, cost £118 7s for building the structure without

fireplaces or windows. Adding three fireplaces and six

windows cost a further £10, 30' of chimney work cost

£4 10s, the dressings for the great gate archway £1

5s and two lintels for the two doors of the flanking towers eleven

shillings. Later some wooden gates at Conway cost

£15 10s. This cost is far greater than the

obviously paltry ‘outer gate' at White Castle in

1257. Add to the Mill Gate the cost of the materials and

labour and the flooring and roofing and we are probably looking at no

less than £300 for building this gatehouse. It is

to be presumed that the final cost of the adjoining curtains and towers

was similar to that of the gatehouse. If White Castle outer

ward (O) was constructed in the 1250s or 1260s we could therefore

expect it to have cost somewhere around the £600

mark. It is doubtful that the expenditure would have been

much less in the 1230s. Certainly walling only half the

outer bailey and adding a twin towered gatehouse at Degannwy between

1250 and 1253 seems to have cost about £1,500, even though

when ordered the cost was expected to be only 300 marks

(£200) for double the work.

Similarly to get an impression of the

cost of the inner ward towers at White Castle we need look no further

than Harlech castle.

There particulars have survived that

clearly show the cost of similar towers built in 1289. The NW tower at Harlech was built 49½' high at

£2 5s per foot at a total cost of £111 7s

6d. The SW tower, 52' high, at a similar price

per foot cost £117. The simple north gate

at the foot of the sea cliff cost £63 5s at £2 15s

per foot, with an unfortunately illegible surcharge for an extra

possibly 14' built on top of the gate. The small

south tower in the outer ward was charged at 12s 2d per foot and

therefore cost £6 1s 8d for the 10' of its

height. Building the battlements on 130' of wall with a

look-out garret on it and seven voussoirs for loops cost

£25. Interestingly a further 50' of

battlements alone cost £15. Another interesting

expenditure was the £45 16s 8d it cost for lead and plumbing

it on to the roofs of the gatehouse and two further towers.

Similarly in 1244 it cost £68 1s 4½d to lead the

roof of the keep at Lancaster. Ten years later ‘a

curtain wall and gateway' at the same castle cost £257 7s

7½d. These costs do not seem greatly different

from that incurred in 1218 when a tower fell down at Kenilworth

castle. Its rebuilding subsequently cost

£150. Obviously this sum did not include materials

as they were already on site, mainly supplied by the collapsed tower.

At White Castle this would give a

probable cost for building the four southern towers of some

£400. The gatehouse would probably have been about

£300 on its own and then there would have been some

£70 to roof them all. In 1292-93 the similar sized

twin-towered gatehouse at St

Briavels castle cost nearly

£500. Of this £415 8s 9½d had

been spent ‘on the construction of the new gateway into the

castle by the king's writ', while an additional £62 11s

¾d had been spent on the purchase of lead for its

roof. When woodwork for the floors and other materials are

taken into consideration at White Castle we are probably looking at a

round figure of about £1,000 for the inner ward

refurbishment, when we add labour and all the extra costs that always

occur this probably brings the total to more like

£2,000. This is a similar sum to that spent by King

John (1199-1216) in making the curtain wall complete with D shaped

towers at Scarborough castle. In total therefore, it would

seem reasonable to suggest that the refurbishment of White Castle cost

some £2,600 - a sum most likely found by Earl Hubert Burgh,

for neither the Lord Edward, nor his younger brother, Prince Edmund,

were either recorded as building anything in the Gwent

Marches. Nor does it seem likely from their histories that

their finances were sufficient to undertake such great rebuildings at

White Castle when they had the opportunity.

One feature that ties the Trilateral

castles together, and therefore suggests that they were constructed as

part of a single building scheme, is the access to the

wallwalks. This would appear to have been gained mainly via

the two individualistic stairways in the gatetower, although there were

likely stairs in the chapel tower (C) at White Castle and in the west

tower at Grosmont. The profusion of wooden steps to wallwalk

level which are occasionally suggested would simply seem to be

imaginary, especially when the number of buildings clustering against

the curtain walls are taken into consideration. At Skenfrith

there is no obvious method of reaching the wallwalk, though it must be

suspected from the rest of the remains, that the original stairway was

in the gatehouse. At Grosmont a straight stair can still be

made out in the gatehouse, although a short stairway in the west tower

appears to allow access to the mid-floor of the west tower, if not the

wallwalk.

Finally, at all three castles of the

Trilateral, the lack of sanitation is immediately obvious. At

White Castle garderobes only certainly exist in the outer ward and

these were obviously built with a fair amount of people in mind, with

two or three in the outer gatehouse (g), two in the west tower (c) and

one against the curtain (f). The pit (V) in the inner ward is

of uncertain purpose. The latrine block by the side of the

great tower at Grosmont may also be an addition to Hubert Burgh's work,

while at Skenfrith the only garderobe, a corbelled out latrine, is set

in the second floor of the king's tower. Perhaps Hubert had

taken to heart the lesson of the loss of Chateau Gaillard by a common

soldier scaling the undefended latrine shaft. Certainly his

provisions for sanitation and light for the common soldier seems

singularly lacking at all three inner fortresses.

This study has revealed much new data

about the history, building and operation of White Castle. It

is also interesting to see how the perceived history of the site has

see-sawed over the years. The great G.T. Clarke believed that

the inner curtain was built during the late 1180s and that Hubert

Burgh was responsible for the rest of the masonry. In 1961

this view was overturned and the dating of the later masonry was

adjusted to the 1250s or 1260s. As I hope to have shown,

this reinterpretation was based upon slim evidence that does not stand

up to detailed scrutiny. Certainly the singular reference to

roof repairs of ‘a tower' in 1257 cannot be taken as evidence

that the old keep (K) was still standing, nor can the inexpensive works

possibly carried out on an outer gate be tied to the refortification of

the outer ward (O).

What can be firmly deduced is that the

rectangular keep (K) could have been built at any time between 1067 and

1160, though perhaps the first push into Gwent by the earls of Hereford

in the late 1060s and early 1070s or the Anarchy of Stephen's reign

would have provided most motivation. It also seems likely

that this keep (K) was built simultaneously with the hall block of

Grosmont castle, Grosmont being the caput and White Castle the major

fortress of the honour. With this in mind it should also be

noted that the only early Norman pottery to come from all three castle

sites is from Skenfrith where a single sherd came from a silted ditch

which was said to have lain under the Hubert Burgh masonry

castle. It is therefore eminently possibly that the later

castles of the Trilateral began as the castles of the Bilateral, and

that Newcastle/Skenfrith was a latecomer to the scheme.

Secondly the northern four towers of the

inner ward at White Castle can be reasonably assigned to the work of

Hubert Burgh, probably in the era 1229 to 1231, and that the two

southern towers and also much of the outer ward probably date to his

work in the period 1234 to 1239. The work carried out to 'the

tower' of Walerand Teuton and his immediate successors in the

mid thirteenth century was far more likely concerned with the

adjustments to the larger south tower (S) than to the obsolete keep (K)

which had most likely already been demolished by Hubert Burgh when the

two great southern flanking towers and joining curtain were

constructed. Certainly parts of the old keep (K) appear to be

reused in the chapel tower (C). It can therefore be seen that

the dating of the construction of White Castle is reasonably secure and

supported by the works of Hubert Burgh at other fortresses.

In total it can be seen that White

Castle as it now stands is primarily an early to mid thirteenth century

enclosure castle built on the site of an earlier keep and bailey

structure. Its great size shows the determination of the

Crown and later Earl Hubert Burgh of Kent in denying this district to

the native Welsh. As such it stands as a masterpiece of

military engineering to the second quarter of the thirteenth century,

just as the Edwardian castles of North Wales stand testament to the

abilities of the last quarter of the century.

Text

extracted

from a full history and architectural description in

Llantilio

or White Castle and the

families of Fitz

Osbern, Ballon, Fitz Count, Burgh, Braose and Plantagenet of Grosmont

Order

through the PayPal

basket below.

Why not join me at other Lost Welsh Castles next Spring? Please see the information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2010

Paul Martin Remfry