The Medieval Rulers

of Sicily

The Hautevilles

Robert Guiscard, 1061-85

Robert was a member of the very minor family of Hauteville from

Normandy. His father was Tancred Hauteville of Hauteville le

Guichard near Coutances. Tancred died in 1041.

Robert was probably the eldest of at least 6 boys by Tancred's second

wife, Fressenda. Consequently, with nothing to inherit at

home - there being at least 5 sons by Tancred's first wife, Moriella -

Robert sought his fortune abroad. After conquering much of

southern Italy and being made duke of Apulia, Calabria and Sicily with

the pope's blessing in 1059, he turned his attention to the conquest of

still Muslim Sicily, to which he now held title, but where he held no power. His initial campaigns there from 1061 to

1072 saw the capture of the northern coast of the island. He

then devoted the rest of his life to helping the pope and trying to

conquer Constantinople as well as keeping a weary eye on his younger

brother, Count Roger of Sicily (d.1101).

Count Roger, 1060-1101

Roger was the youngest son of Tancred and Fressenda and soon went south

to join his elder brother, Robert. However, their

relationship was not the happiest and there seems to have been an

element of jealousy from Robert against his younger sibling that

occasionally led to tension. Roger was first to invade Sicily

in an unsuccessful expedition in 1060 which initially captured Milazzo

castle. In 1061 both brothers, acting in harmony, returned

and secured Messina and Paterno as well as building a castle at San

Marco d'Alunzio. In 1071 Roger was made count of Sicily by

his elder brother and the next year they jointly took

Palermo. It was only after Robert's death in 1085, when Roger

took control of the other half of Messina and the northeastern corner

of Sicily known as Val Demone, that the count could move decisively

against the remaining Arab fortresses. In 1091, Noto, the

last Muslim stronghold, made terms and Roger became de facto ruler of

the island. In the same year his nephew, Roger Borsa

(d.1111), granted his inheritance in Palermo to Roger. For

the last 10 years of his life Roger was active in reforming Sicily and

campaigning on the mainland.

Count Simon, 1101-05

Simon never wielded power in Sicily, dying in 1105 at the age of

12. His mother, Adelaide Vasto (d.1118), was his regent.

Count Roger, 1105-30

Roger was the younger brother of Simon and inherited the title of count

of Sicily from him without trouble - again under the regency of his

mother. This ended in 1112. In 1122 Duke William of

Apulia (d.1127), the son and heir of Roger Borsa, renounced to Roger

his remaining rights in Sicily as heir of Robert Guiscard

(d.1085). Roger went on to succeed him on his heirless death

in 1127 and became the senior Hauteville in southern Italy.

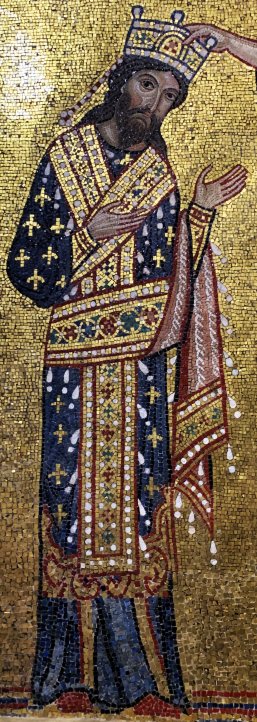

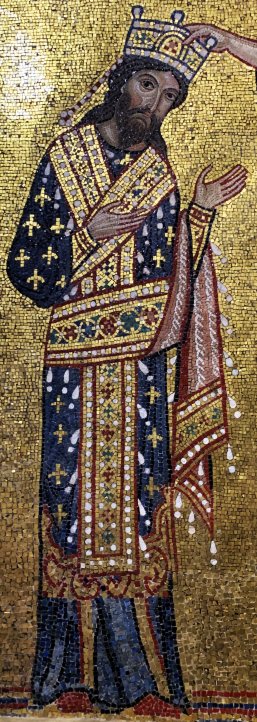

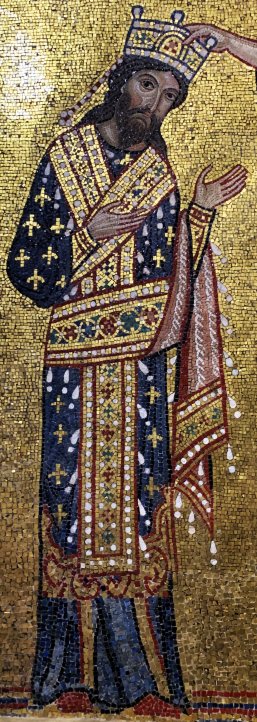

King Roger, 1130-54

King Roger, 1130-54

In 1130 Count Roger was made king of Sicily (which included much of

southern Italy) by the antipope Anacletus II (1130-38), being crowned

in Palermo cathedral on Christmas day. This resulted in a 10 year war

against Pope Innocent II (1130-43) and his royal backers, Louis VI of

France (1108-37), Henry I of England (1100-35) and Lothair III of

Germany (1133-37). In 1139 Roger's forces captured Pope Innocent II,

bringing the war to an end with a satisfactory peace treaty between

them, Anacletus having died in 1138. In 1140 Roger

inaugurated a new coinage, called the ducat. This became the

normal Italian currency for centuries. The same year he

reformed his Sicilian realm to strengthen it both militarily and

economically. The result was a golden age for Sicily which

attracted to Roger's court such men as Muhammad al-Idris, the

geographer and Nilus Doxopatrius, the Byzantine historian. He

also imported Englishmen, Arabs and Greeks to his court was well as

Normans and Frenchmen. The Greek George Antioch, the builder

of the Martorana or the Church of St Mary of the Admiral, became his

first emir of emirs, or admiral and produced the attached mosaic of Roger in that church. Between 1135 and 1148,

Roger's forces conquered much of the African coast opposite Sicily and

even warred successfully against Byzantium, capturing the silk weavers

of Thebes who were then set to business in Palermo.

According to Romuald's chronicle, King Roger spent his last years

working to convert all his Jews and Muslims to Christianity.

Presumably these converts were noble as no incentives were given to

peasants to change faith. Roger's Catholicism is exemplified

by his execution of Admiral Philip of Mahdia, who had reverted to Islam

in the last months of 1153. Perhaps Roger's greatest

achievement was to hire the exiled Moroccan Prince Idrisi to write his

Book of King Roger which detailed the geography of Sicily as well as

commenting on the rest of the known world. A silver map of

the world was also made to go with this work, but this was stolen and

melted down during the 1161 uprising. Unfortunately the

claims put forward in later years for the book were never realised and

it remained a forgotten treasure that had little impact on

Sicily. King Roger, corpulent, but still intelligent, died at

the age of 58 in Palermo on 26 February 1154 of a fever.

William I, 1154-66

The only surviving son of King Roger was about 24 when he inherited the

throne, having been crowned joint ruler with his father in

1151. The chronicler, Hugh Falcandus, who loathed nearly

everybody he wrote about, described him as cruel, suspicious, indolent

and foolish. Consequently by the fourteenth century, he was

known as William the Bad and his son as William the Good.

However, judging by their reigns, for most Sicilians the titles would

appear to be reversed, as chaos ruled under the younger William, while

the elder tended to keep the baronage in check. Despite

Falcandus' claims that William was all but useless, he was regularly

used by his father at his court from 1142 onwards and one surviving

dedication by Henry Aristippus, claims that William was a patron of the

arts just like his father. Certainly the pope thought that

King William I was suspicious of his barons and that his widow, during

the minority of William II, reversed this policy of suppression of the

baronage and allowed all those exiled to return home.

The young William continued his father's policy of ruling through low

born advisors or new men, just like Henry I (1100-35) and Henry II

(1154-89) did in England, and keeping the barons out of

government. This led to several revolts against his main

advisor, Maio of Bari, the builder of San Cataldo church. On

assuming power William faced a revolt in Southern Italy encouraged by

Pope Adrian IV (1154-59), Emperor Manuel Komnenos of Byzantium

(1143-80) and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1147-90). In 1156

the king defeated the Greeks and made peace with the pope, but his

African domains were overrun by 1160. This was the only dark

side in the early part of the reign that had seen all the king's

enemies bar the Holy Roman Emperor neutralised. With this the

reorganisation of the dioceses undertaken under Pope Anacletus

(1130-38) was accepted, although Cefalu and Lipari had to wait until

1166 for their formal recognition. All in all the reign had

started successfully.

However, the Sicilian nobles, to the great pleasure of the chronicler

Falcandus, proceeded to murder Maio on 10 November and then, in an

abortive uprising, stormed the Norman palace on 9 March 1161, capturing

the king. This led during the ensuing debacle on 11 March, to

the killing of William's heir, Roger. After destroying the

rebellion and killing its leader, Matthew Bonellus of Caccamo and

Mistretta, the rest of William's reign proved relatively peaceful, but

he died young in May 1166 aged only about 45, having solved his

father's papal problems as 'the faithful and devoted son of the

church'. He was buried in his palace in the Cappella Palatina (St Peter's chapel),

although his son had him reburied at Monreale cathedral before 1189.

During his reign and probably at the end of that of his father, there

was a demographic change in the kingdom with the mass immigration of

Latins from the Continent to the island. They mostly settled

in Palermo and the southeastern Noto region. This helped lead

to the anti-Muslim pogroms of 1161 in both these places and the Islamic

centre and west of the island, particularly the Val Marsala, receiving

the displaced Muslim populations.

William II, 1166-89

On the early death of his father, Sicily was ruled by his mother,

Margaret Navarre, as regent. Her first act was to release all

prisoners and then cut taxes. Both may have bought her some

popularity, but in the long term this policy must prove

disastrous. During this period she initially relied on her

French relatives, and in particular Stephen Perche (d.1169), a young

man who probably never reached 30. Stephen arrived in Sicily

with an entourage of 37 in 1167. About 1174 one of these,

Peter Blois (d.c.1211), noted that he was one of only 2 of them still

alive. Perche was specially brought in as it was thought he

would be above the local squabbles of the aristocracy.

However, his rule succumbed to just such factionalism and he was

eventually overthrown in 1168.

In 1171, aged 17, William II was declared of age, although, Peter Blois

(d.c.1211), an intimate of Stephen Perche (d.1169), commented that

William was a most ill advised youth and took treacherous

counsel. Others recorded that the king ‘paid too

much attention to his astrologers'. The result was a council

riven with faction between Archbishop Walter of Palermo (d.1191) and

Matthew, the vice chancellor. Both men loathed one another.

In 1177 William married Joan, the daughter of Henry II of England and

Eleanor of Aquitaine. Their son, Duke Bohemond of Apulia, was

born and died in 1181 and no further children followed. This

marriage was the first real political contact between England and Sicily and gave

rise to the Norman myth of their joint foundations by

‘Normans' in the late eleventh century.

In 1186 William married off his 30 year old half sister to the future

Emperor Henry VI (1169-97) and made her his heir presumptive to his

realm. This allowed him to go Crusading against Saladin

(1174-93) and Byzantium. However, he died aged only 36 in

November 1189, thus plunging his realm into chaos, with his widow,

Queen Joan, as well as many members of the aristocracy, openly

supporting the claim of William's designated heiress, Constance and

therefore her German husband, Henry VI.

On the king's death, the Latins of Palermo again attacked their Muslim

neighbours. This led to another exodus to the interior of the

island and the revolt of the Saracens of Western Sicily based upon the

area around Segesta. This revolt was not finally crushed

until the campaigns of Frederick II (d.1250) in the 1220s.

Interestingly in the prelude to this rebellion, Ibn Jubayr visited

William's court and noted that it consisted of those of his own

religion 'all, or nearly all, concealing their faith, yet holding firm

to the Muslim divine law'.

Count Tancred of Lecce, 1190-94

An illegitimate son of Count Roger's eldest son, Duke Roger III of

Apulia (d.1148), Tancred had taken part in the baronial opposition to

King William I (d.1166) at first Palermo in 1160 and then Piazza

Armerina in 1161, but had survived, taking exile in Constantinople,

before returning in 1166 upon the accession of his cousin, King William

II (d.1189). During this time he was known as the count of

Lecce. His short stature and visage led his enemies to

christen him The Monkey King. He Crusaded unsuccessfully for

William II in 1174 and on William's death in 1189 seized the

throne. In this he was backed by the official class of

Sicily, but opposed by the nobles who were more inclined to support his

aunt and uncle, Constance and King Henry VI of the Romans.

Tancred's rule was not a happy one. Initially he was attacked

by Richard I of England (1189-99) and Philip Augustus of France

(1180-1223) who were passing by on Crusade. This resulted in

the English capture of Messina and Tancred having to buy the approval

of the two foreign kings. This was followed by war with Henry

VI (1169-97) who was now Holy Roman Emperor. During the

fighting the Empress Constance was captured, although she soon regained

her freedom after being transferred to the pope's custody.

Tancred died young at age 56 on 20 February 1194, two months after the

death of his eldest son and heir, Roger.

William III, 1194

Tancred's widow, Queen Sibylla, declared herself regent for her next

son by Tancred, the 4 year old William III. However, there

was no fight left in the kingdom and Henry VI and Constance, buoyed by

the money they had squeezed from Richard I of England for his ransom,

had advanced through southern Italy and then Sicily virtually without

opposition. The queen and her young charge took refuge in

Caltabellotta and from there negotiated a surrender. William

then attended the Christmas crowning of his great uncle and aunt at

Palermo, before being seized with his mother and their supporters 4

days later on an alleged charge of treason. He was apparently

castrated and blinded in Germany and died there in 1198. His

mother and one of his 3 sisters lived out their days in obscurity in

France after their release.

Queen Constance, 1195-98

Born posthumously to King Roger in 1154, Constance was the last of the

main line of the Hautevilles and heir presumptive since 1172.

She was kept under close confinement by her family and it was only in

1184 that she was allowed to marry, presumably after William II had

decided that he was unlikely to have any heir of his own.

When she left Sicily for Germany, King William had his 3 main nobles,

Tancred of Lecce (the future king), Roger Andria (d.1190) and Matthew

Ajello (d.1193),

swear loyalty to her as heiress to the throne. This did not

stop the 3 abandoning her cause and making Tancred king on William's

unexpected death in 1189. In 1191 Constance remained in

Salerno when her ill husband returned to Germany after his failed

attempt to overthrow King Tancred. There she

was turned upon by the locals, captured and imprisoned in Ovo castle in

Naples. She was then half released and half escaped in 1192,

before returning with Henry VI in 1194, with a giant army that met

little opposition in its victorious march to Palermo.

However, she had to wait in southern Italy due to her pregnancy with

the future Emperor Frederick II (d.1250). After giving birth

she was crowned early in 1195 and left to rule Sicily when her husband

returned to Germany. After Henry's return and death in 1197,

Constance had the 3 year old Frederick crowned as king of Sicily in May

1198, all but revoking the boy's rights to Germany. Possibly

realising her own mortality, she placed the boy in the care of Pope

Innocent III (1198-1216) and then died that November.

The Swabians

Emperor Henry VI, 1194-97

Henry, as king of the Romans, had married Constance the posthumous

daughter of King Roger (d.1154), in 1186. Having failed to

dislodge King Tancred from Sicily in 1191, Henry returned in 1194 with

a great army, paid for by the ransom of King Richard I of England

(1189-99), whom he had held imprisoned since the end of the third

Crusade in 1193. In March 1195, Henry made Constance queen of

Sicily

After disposing of his rival, William III, Henry played international

politics until a revolt in Catania during 1197 brought him to Messina

in March. After rapidly crushing the revolt with German

soldiers he intended to set off for the Holy Land, but died at the port

on 28 September at the age of only 31, presumably a victim of a war

related disease or malaria.

Emperor Frederick II, 1198-1250

At the age of only 3, Frederick became king of Sicily, and was placed

under the care of Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) by his dying mother.

Sicily then descended into anarchy until 1208 when Frederick began to

take control of his kingdom at the end of his minority. A

noted polyglot speaking 6 languages, Latin, Sicilian, German, Occitan,

Greek and Arabic, Frederick was an avid patron of science and

art. As such, like his wife Isabella's grandfather, Henry II of

England (1154-89), he outlawed trial by ordeal as superstitious.

Frederick's reign began badly. After his mother's death his

uncle, Philip of Swabia (1198-1208), invaded Sicily in 1200 and seized

Frederick the next year. He then ruled Sicily until 1202 when

he was succeeded by the German, William Capparone, who kept Frederick

under his power until 1206. In 1208 Frederick was declared of

age at 14 and began to reassert his power over the barons and

adventurers who had usurped his royal authority. Despite

this, Frederick was absent from Sicily from 1212 until 1220 when he

pursued his inheritance in Germany.

In 1220 Frederick became Holy Roman Emperor, but obviously preferred his

domain in Southern Italy and Sicily where he mostly resided from then

on. Suppressing the revolt of the Muslims of Entella, Segesta

and Iota, he destroyed some castles and relocated their inhabitants to

Lucera on the mainland from 1223 onwards. In 1231 he issued

his Constitutions of Melfi, which might be compared to Henry II's

Constitutions of Clarendon, except by this mode Frederick made himself

an absolute monarch of Sicily. This code remained the basis

of Sicilian law until 1819. Although his kingdom remained peaceful,

war raged throughout Italy and Germany as the pope sought to overthrow

the emperor. This also caused simmering discontent on the

island due to the high level of taxation necessary to finance the

war. Eventually Frederick died in Apulia of dysentery aged

only 56 in 1250. He was buried in Palermo cathedral with his

Hauteville ancestors, the mummified body surviving intact until

1781. Frederick's scientific book on falconry, The Art of

Hunting with Birds (De arte venandi cum avibus) is also the first

authored by a king to survive.

Conrad IV, 1250-54

With the death of Frederick in 1250 riots occurred in the kingdom of

Sicily and Conrad was obliged to rely on his half brother, Manfred, to

govern the kingdom. In 1253 the pope offered Sicily to King

Henry III of England (1216-72) for his son, Edmund (d.1296), which

helped begin a civil war in England. Eventually the pope turned

to Henry III's cousin once removed, Charles Anjou (d.1285), as champion

against the Swabians in Italy. Conrad was excommunicated and

died of malaria in 1254. He was only 26.

Conradin, 1254-58

The 2 year old heir to Conrad IV was left under the regency of his

Uncle Manfred in Sicily. In 1258 Manfred had himself

proclaimed king of Sicily, leaving Conradin, who was claimed to be

dead, as merely duke of Swabia. In 1267, after the death of

his Uncle Manfred in battle against Charles Anjou (d.1285), Conradin

marched into Italy while a Castillian fleet landed at

Sciacca. Consequently most of Sicily, except for Palermo and

Messina, revolted from the Angevins to his cause. After

military reversals in Italy, Conradin was captured when making for

Sicily and executed by King Charles Anjou on 29 October 1268.

He was only 16.

Manfred, 1258-66

He was the illegitimate son of Frederick II (d.1250), although the

emperor regarded him as legitimate and made him prince of

Taranto. He became regent of Sicily for his half brother in

1250, although he was effectively stripped of this in 1252.

He became regent again for Conradin in 1254, until his usurpation of

the throne in 1258. During this time he was excommunicated

for refusing to hand Sicily over to the pope who had been named

guardian by Conrad IV (d.1254). When a rumour reached Sicily

that Conradin had died in 1258, Manfred immediately seized the throne

and refused to abdicate when Conradin's envoys arrived demanding him to

do so. In Sicily his rule proved popular when he claimed that

the Sicilians needed a strong local ruler. After claiming the

Imperial title in 1263, he was defeated and killed by Charles Anjou

(d.1285), who had been invested with Sicily by the pope. He

was only 34.

After the battle King Charles captured Manfred's second wife, Helena,

and her children and imprisoned them miserably until their deaths,

although one son, Frederick, supposedly escaped his imprisonment and

fled to Germany, eventually dying in Egypt in 1312.

The Angevins

Charles, 1266-82

Charles was the youngest son of King Louis VIII of France (1223-36) and

although destined for the church became count of Provence through is

marriage to Beatrice, the heiress of Count Raymond Berenguer IV of

Provence (d.1245). Crowned king of Sicily on 5 January 1266,

he took a Crusading army alleged to be 6,000 cavalry, 600 mounted

bowmen and 20,000 infantry, with him to Southern Italy where he killed

King Manfred at the battle of Benevento. Philip Montfort then

occupied the island of Sicily for him without resistence.

Towards the end of 1267 Sicily rose in revolt and remained so even

after the defeat and death of Conradin in 1268. Philip and

his relative, Guy Montfort, the son of the English rebel, Earl Simon

Montfort of Leicester (d.1265), were sent with an army to reduce

Sicily, but only managed to take Augusta, the royal fortress of

Frederick II (d.1250). The next year, after August 1269, the

Angevin army captured Agrigento and forced the remaining rebels to

surrender in early 1270. Charles then spent a month in Sicily

before sailing to Tunis for the abortive Eighth Crusade. On

his return his fleet was all but wrecked at Trapani under the watchful

view of Erice. Before leaving the island the king granted

temporary tax concessions due to the devastation the fighting during

the rebellion had caused in Sicily.

In 1271 Charles left the island never to return, although he often

demanded increased taxes to pay for his expensive foreign wars as well

as restore old fortresses and build new ones, one of which was

Castelbuono. After 1279 many Sicilians were forced into

Charles' armies while the capital of Sicily was moved from Palermo to

Naples. Further, some 700 French nobles were transplanted

into the kingdom, much to the annoyance of the locals. The

result was the uprising known, since the sixteenth century, as the

Sicilian Vespers. This resulted in King Peter III of Aragon

(d.1285) seizing the throne. Possibly this part of the plan

of the Vespers, or more likely the revolt, had been paymastered by

Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos of Byzantium (1261-82) to

take Angevin pressure off his lands. Certainly the leaders of

the revolt seem to have had different objectives, Walter Caltagirone

before July 1283 seizing the royal Sperlinga castle from the Aragonese

in a forlorn bid for total Sicilian independence. Regardless,

Charles failed to return to the island and died while preparing for

another Sicilian adventure in Brindsi at the age of 58.

Interestingly enough, he had tried his hand as an architect in that

city, building a tower for himself. It collapsed.

The Aragonese

Peter I, 1282-85

Peter, the husband of King Manfred's eldest daughter, Constance (d.1302), claimed the

throne after the Sicilian Vespers of 1282 and accepted the loyalty of

most of the island against the Angevins. The result was the Crusade

against Aragon which ended with the defeat of the French and the death

of King Philip III of France from dysentery at Perpignan in October

1285. Peter died just a month later, probably of similar

causes, aged about 46.

James, 1285-95

As second son, James succeeded to Sicily on the death of his father and

also became king of Aragon with the death of his elder brother, Alfonso

III in 1291. In 1295 he ceded Sicily to King Charles of

Naples (d.1309) in making his peace with the papacy, but the island

rebelled and installed James' brother Frederick as king.

Frederick III, 1295-1337

Frederick was made regent of Sicily by his brother, King James, when he

became king of Aragon in 1291. The brothers were both

children of Constance, the daughter of King Manfred (d.1266).

Following the treaty of Anagni on 10 June 1295, by which James granted

Sicily to the church who would subinfeudate the island to Charles of

Naples (1285-1309), Frederick seized power on 11 December 1295 and was

crowned king on 25 March 1296. This led to a continuation of

the war between Charles of Naples and Sicily and the adherence of John

Procida (d.1298) and Roger Lauria of Aci, Calatabiano and Tripi (d.1305) to the

Angevins. After the defeat of the Sicilian navy by Lauria, Robert Naples (d.1343) and his brother, Count Philip of Taranto (d.1331) invaded Sicily in 1299

and took Catania, before being defeated by Frederick. The war

was only ended in 1302 by the treaty of Caltabellotta. This occurred while Charles was

investing Sciacca.

By this Frederick was recognised as king

of Trinacria, rather than Sicily to save face for the pope and the

kings of Naples. He was also to marry Charles' daughter,

Eleanor (d.1341), the kingdom reverting to Naples on Frederick's death

and their children receiving compensation elsewhere. In the

subsequent period of peace, Sicily recovered some of its former wealth.

However, in a fit of religious mania that swept the country, the war

was resumed from 1313 to 1317 and Frederick was excommunicated in

1321. In 1325 Giovanni Chiaromonte (d.1339), the lord of

Agrigento, Favara and Mistretta, came to the fore when he defeated King

Robert of Naples (1309-43) in a naval battle off Palermo. The

war finally ended in 1335, with major campaigns having been fought in

1325-26, 1327, 1333 and 1335. Despite the end of the war,

Giovanni Chiaromonte (d.1339) went over to Naples due to a private dispute and

the kingdom of Sicily was all but ruined by the incessant warfare and

resultant slackening of trade, plus a deterioration in the climate that

struck all Europe in the early fourteenth century. This

cooling led to food crises occurring between 1311 and 1335 and the

economy all but collapsing after 1321. Added to this Mount

Etna erupted in 1329 and 1333. Frederick died 2 years after

the unstable peace was achieved, aged 65.

Peter II, 1337-42

Despite the treaty of Caltabellotta, Frederick was succeeded by his

eldest son, Peter, who was 33. Peter was not created in the

image of his father and was portrayed as feeble minded. His

kingdom rapidly broke down into civil strife between the leading

families of Ventimiglia who held Castelbuono and Garaci Siculo and the

Alagona of Aci, Delia and Paterno. These 2 led the

Catalan/Aragonese faction. They were opposed by the

Latin/Angevin faction led by the Chiaramonte of Caccamo and Vicari and

the Palizzi of Calabria on the other side of the Messina

strait. The latter gained the support of Queen Elizabeth

(d.1349), Peter's wife, while the former found favour with Elizabeth's

brother in law, Duke John of Randazzo (d.1348).

King Peter continued the ongoing war with Naples, losing the Lipari

islands and even Milazzo to them. He died young in August

1342, aged 38.

Louis, 1342-55

Louis was only 4 when crowned king and a regency was appointed under

his uncle, Duke John of Athens. He achieved a peace treaty

with Naples at Catania in 1347. Unfortunately, he died of the

plague in 1348 and the regency passed to Count Matthew Palizzi and

Queen Elizabeth, until her death before July 1349. In 1350 a

tripartite division of Sicily was proposed between the 3 competing

noble houses of Ventimiglia, Chiaromonte and Palizzi, but this only led

to a 3 month truce. A second attempt in 1352 lasted only a

year. In 1353 Louis with his Chiaromonte supporters marched

on Castroreale and visited Milazzo and Taormina before retiring to

Messina where his guardian, Matthew Palizzi, was killed by Count Simon

Chiaromonte, the king fleeing to Ursino castle by boat. After

an abortive attack on Milazzo the king declared the Chiaromonte

traitors. From Catania he moved to Agira castle, but failed

to take Enna. He also moved on Taormina and failed to take

Calatabiano castle that November.

In April 1354, King Louis of Naples (1352-62) sent an invasion force to

Sicily that took Palermo and then, in alliance with the Chiaromonte,

took most of Sicily leaving the young King Louis with only Catania with Ursino castle and

Messina. In June Louis forgave the Ventimiglia family and

then marched on Piazza Armerina, retaking much of southern Sicily and

only being baulked at Castronovo. On 7 January he reached

Giuliana castle, but retired on Catania where bubonic plague broke out

on 10 July 1355. He then moved to Messina and attacked

Palermo by sea, before returning to Catania where he was struck by the

plague. He retired to Aci castle where he died on 16 October

1355, aged just 17.

Frederick IV, 1355-77

Frederick began his reign under the regency of his sister, Euphemia

(d.1359), but power lay in the hands of Artal Alagona (d.1419) of Aci

castle. In 1372 he finally arranged peace terms with Naples

which was negotiated by the Chiaromonte. By this Frederick

accepted the title king of Trinacria rather than king of

Sicily. The treaty of Villeneuve was sealed with the king

marrying Antoinia Baux, but the marriage proved childless and on

Frederick's death the throne passed to his only daughter from his first

marriage, Maria. He was only 36 when he died.

By the end of Frederick's reign the wars, heavy rainfall and plagues

had led to a fall in Sicily's population from an alleged 850,000 in

1277 to only 350,000 in 1377.

Queen Maria, 1377-1401

Succeeding aged 13, her father had named Artal Alagona (d.1419) of Aci

to be her regent. However, in reality power was split between

him and 3 other vicars, Count Francesco II of Ventimiglia (d.1391), who held

Castelbuono, Gangi, Geraci Siculo, Pollina, Pettineo, Rocella and

Sperlinga; Count Manfred III Chiaromonte of Modica (d.1391), who held Modica, Mussomeli and Vicari and finally Count William Peralta of Caltabellotta (d.1394), the

lord of Caltanissetta. Each ruled in their own

lands. In 1384, after a series of kidnappings and rescues,

Maria was married to Martin of Aragon (d.1409), who thereby became

titular king of Sicily. However, it was not until 1392 that

the couple returned to Sicily with an invasion force, defeated the

opposing barons and began to rule.

Martin, 1392-1409

On Maria's death at the age of 38 in 1401, the king repudiated the

treaty of Villeneuve of 1372 and ruled Sicily in his own name, no

longer offering allegiance to the pope or Naples. After

invading Sardinia, Martin died suddenly of malaria. He was

little more than 33 years old.

Martin II, 1409-10

Martin II was the father of King Martin of Sicily, which kingdom

reverted to his Crown on his son's death. When the senior

Martin had succeeded to the kingdom of Aragon in 1396, he had remained

in Sicily due to the problems his son was having with the barons there,

while his wife acted as his representative in his peninsula kingdom

until he returned home in 1397. As Martin left no heirs, and

castles were becoming militarily obsolete by this time, he makes a good

point to leave this survey of Sicilian rulers.

Copyright©2023

Paul Martin Remfry

King Roger, 1130-54

King Roger, 1130-54 King Roger, 1130-54

King Roger, 1130-54