Hawarden

It

has been suggested that Hawarden castle lies on top of earlier,

prehistoric, earthworks. This is not impossible, but it should be

noted there is another apparent motte and bailey castle in Hawarden

only half a mile to the NW. Whether this was a castle or a

tumulus is another matter. In 1086 there was no mention of a

castle although the vill of Haordine

was a part of Domesday Cheshire. The castle may have been built

before the wars of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd (d.1282), when it was held by

the Mohaut family of nearby Mold. As their castle at Mold seems

not to have progressed beyond the timber phase it is possible that this

was their main caput, as this fortress, 5 miles to the west of

Hawarden, continually fell to Welsh forces.

It

has been suggested that Hawarden castle lies on top of earlier,

prehistoric, earthworks. This is not impossible, but it should be

noted there is another apparent motte and bailey castle in Hawarden

only half a mile to the NW. Whether this was a castle or a

tumulus is another matter. In 1086 there was no mention of a

castle although the vill of Haordine

was a part of Domesday Cheshire. The castle may have been built

before the wars of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd (d.1282), when it was held by

the Mohaut family of nearby Mold. As their castle at Mold seems

not to have progressed beyond the timber phase it is possible that this

was their main caput, as this fortress, 5 miles to the west of

Hawarden, continually fell to Welsh forces.

The first certain mention of Hawarden comes around 1200 when Ralph

Mohaut made a grant that was witnessed by one Master Hugh Hawarden (Haurdin).

This implies a settlement with a church in the vill. As such it

is not impossible that a castle was founded by this time, especially as

the Mohauts were to repeatedly loose control of Mold. With Mold

mostly being under Welsh control it seems possible that Hawarden was

the main Mohaut castle during the thirteenth century. A

functional castle would appear to have been operating at Hawarden on 26

October 1260 when the Lord Edward sent Urien St Peter to Hawarden for a

year's service. Roger Mohaut had died in June 1260 and Edward, as

lord of Chester, had obviously taken over the castle. Three years

later he agreed to Dafydd ap Gruffydd (d.1283) having shelter when

necessary in the baileys of Hawarden or Shotwick castles. After

the capture of the Lord Edward, Henry Montfort met Prince Llywelyn ap

Gruffydd (d.1282) at Hawarden, where they gave each other the kiss of

peace and put an end to the 8 years of warfare that had been raging

between the men of Cheshire and Gwynedd. After Edward regained

his freedom and smashed the barons at the battle of Evesham in 1265,

Prince Llywelyn moved against him and in September besieged, took and

destroyed Hawarden castle. By the terms of the treaty agreed at

Montgomery 2 years later, Hawarden and its castle were to be returned

to Robert Mohaut, but the fortress was not to be rebuilt for 30 years,

ie until 1297.

With Llywelyn's defeat in 1277 that treaty was discarded and a new

treaty made at Conwy. As a consequence of this, Hawarden castle

was re-occupied by Kenwrick Sais on behalf of Edward. He may well

have refurbished the castle over the next 4 years and in 1281 it was

handed over to Roger Clifford Senior (d.1286). On the night of

21/22 March 1282 Dafydd ap Gruffydd attacked the castle and seized

Clifford, executing most others found within the fortress. This

began the final war of princes Llywelyn and Dafydd, which only ended

with their deaths. After the war Hawarden was again refurbished

and handed over to the heir, Roger Mohaut, only for the castle to fall

again at the beginning of Madog ap Llywelyn's revolt in 1294.

Hawarden eventually passed to the Stanleys who entertained Henry VII

here twice. In the Civil War the castle was tamely surrendered to

Thomas Middleton of Chirk castle on 11

November 1643, although it was retaken for the king after a short siege

on 7 December. The city and castle of Chester finally surrendered in

February 1646 and Hawarden castle, on royal orders, the next

month. It was then laid waste.

Description

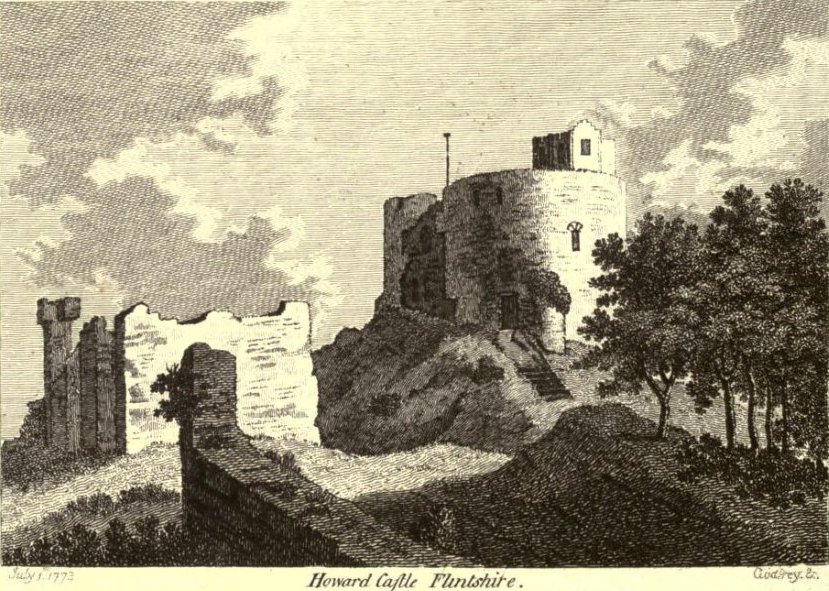

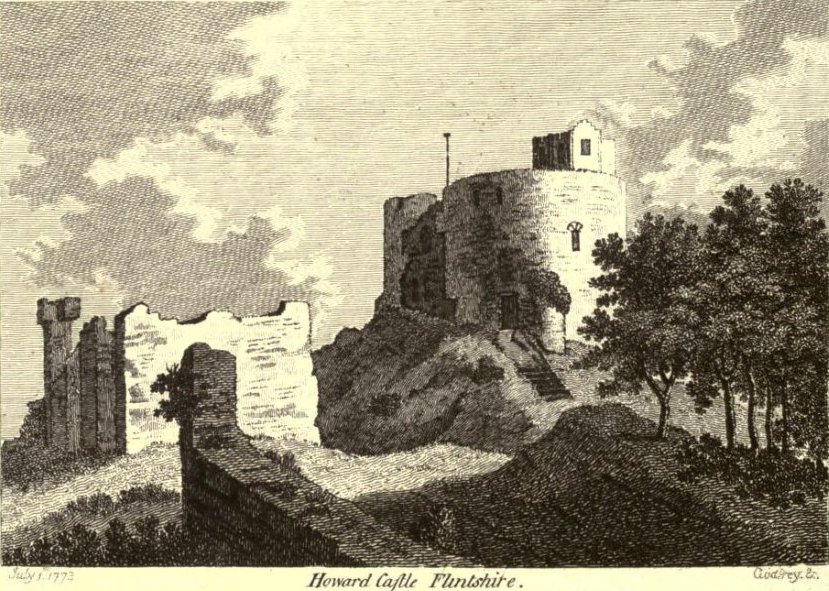

The castle is a typical motte and bailey, with the motte on the end of

a ridge facing SW. To the NE is the bailey, while to the SE lies

a strong counterscarp bank to the motte, similar to the one at Whittington.

The motte is about 80' high at the back and some 30' higher than the

bailey, while the polygonal ward is about 180' across. Additional

earthworks to the east and SE are thought to be Civil War works.

The bailey was enclosed with a polygonal wall some 7' thick which ran

up the motte to join the round keep, just as occurs at the similarly designed

and sized tower keeps at Barnstaple (65' diameter, 16' walls), Berkhamsted

(58' diameter, 8' walls) and Plympton (50' diameter, 8' walls). A

similar design is used with the smaller keeps on mottes as

found at Bronllys, Caldicot, Chartley, Hertford, Huntington, Longtown and Miserden. The round keep nearest to Hawarden, which is the biggest such keep, is New Buckenham which has a 65' diameter with 11' thick walls. It should also be noted that Barnstaple, Berkhamsted

and Plympton keeps are so large they are often called shell keeps,

rather than towers.

At the SE apex of the bailey was a solid, 22'

diameter D shaped tower, while the main entrance to the north has been

much altered to the west. Possibly it was originally an internal

gatetower like Llanstephan. The

projecting barbican with great drawbridge pit is impressive, but sadly

no more than foundations now. The hall was between the D shaped

tower and the ‘offices' a later rectangular structure some 60'

across and projecting 35' from the curtain. At the base of the

motte are a jumble of rooms of uncertain date and purpose. Steps

ran up the motte on the south curtain and probably on the north too to

allow these wall tops to be manned. The entrance to the keep

seems to have been a covered stairway up the north curtain, similar to

that at Launceston. There are 2 shoulder headed posterns in this north wall, one at the top of the motte, the other at base.

On

the motte is an unusual 2 storey round keep, 61' in diameter at the

base of the plinth, with walls nearly 15' thick, but dropping to about

13' at rampart level. It is over 40' high. Entrance was

gained to the NE via a broad stair buttress, only about 18" deep which

dies back into the main wall about 5' below the current summit.

Unfortunately this entire structure appears to be a Victorian

rebuild. The gate is protected by a portcullis, similar to the

one into the shell keep at Arundel.

Entering through the gate gives access to a spiral stair to the south

and a small chamber to the north. Beyond is the circular ground

floor room, some 30' in diameter. The room above is similar, but

octagonal and the embrasures in both are shoulder headed

(1250-1350). The chapel is above the entrance and like all below

has been ‘restored' - the peculiar trefoil doorway giving the

game away. Apparently the gate, portcullis chamber and much of

the vice and chapel and a great part of the mural gallery were rebuilt

under Sir Stephen Glynne. This level also has an internal

passageway around the interior of the wall allowing for 5 loops to

cover the vulnerable side of the tower. This bears some

similarity to the towers and walls of Caernarfon castle,

though which castle copied which is a moot point - if they did.

The idea that the similarities in style mean that Master James of St.

George must have had an input in its design is again little more than

fanciful speculation. Indeed the widespread rebuildings to the

keep makes its plan quite suspect in many respects.

On

the motte is an unusual 2 storey round keep, 61' in diameter at the

base of the plinth, with walls nearly 15' thick, but dropping to about

13' at rampart level. It is over 40' high. Entrance was

gained to the NE via a broad stair buttress, only about 18" deep which

dies back into the main wall about 5' below the current summit.

Unfortunately this entire structure appears to be a Victorian

rebuild. The gate is protected by a portcullis, similar to the

one into the shell keep at Arundel.

Entering through the gate gives access to a spiral stair to the south

and a small chamber to the north. Beyond is the circular ground

floor room, some 30' in diameter. The room above is similar, but

octagonal and the embrasures in both are shoulder headed

(1250-1350). The chapel is above the entrance and like all below

has been ‘restored' - the peculiar trefoil doorway giving the

game away. Apparently the gate, portcullis chamber and much of

the vice and chapel and a great part of the mural gallery were rebuilt

under Sir Stephen Glynne. This level also has an internal

passageway around the interior of the wall allowing for 5 loops to

cover the vulnerable side of the tower. This bears some

similarity to the towers and walls of Caernarfon castle,

though which castle copied which is a moot point - if they did.

The idea that the similarities in style mean that Master James of St.

George must have had an input in its design is again little more than

fanciful speculation. Indeed the widespread rebuildings to the

keep makes its plan quite suspect in many respects.

The site was greatly affected by landscaping associated with the New

Hawarden Castle Park and there are records of restoration and

improvements by George Shaw in the 1860s and by R.S. Weir in the 1920s.

Why

not join me at other Lost Welsh Castles next Spring?

Please see the information on tours at Scholarly

Sojourns.

Copyright©2019

Paul Martin Remfry

It

has been suggested that Hawarden castle lies on top of earlier,

prehistoric, earthworks. This is not impossible, but it should be

noted there is another apparent motte and bailey castle in Hawarden

only half a mile to the NW. Whether this was a castle or a

tumulus is another matter. In 1086 there was no mention of a

castle although the vill of Haordine

was a part of Domesday Cheshire. The castle may have been built

before the wars of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd (d.1282), when it was held by

the Mohaut family of nearby Mold. As their castle at Mold seems

not to have progressed beyond the timber phase it is possible that this

was their main caput, as this fortress, 5 miles to the west of

Hawarden, continually fell to Welsh forces.

It

has been suggested that Hawarden castle lies on top of earlier,

prehistoric, earthworks. This is not impossible, but it should be

noted there is another apparent motte and bailey castle in Hawarden

only half a mile to the NW. Whether this was a castle or a

tumulus is another matter. In 1086 there was no mention of a

castle although the vill of Haordine

was a part of Domesday Cheshire. The castle may have been built

before the wars of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd (d.1282), when it was held by

the Mohaut family of nearby Mold. As their castle at Mold seems

not to have progressed beyond the timber phase it is possible that this

was their main caput, as this fortress, 5 miles to the west of

Hawarden, continually fell to Welsh forces.  On

the motte is an unusual 2 storey round keep, 61' in diameter at the

base of the plinth, with walls nearly 15' thick, but dropping to about

13' at rampart level. It is over 40' high. Entrance was

gained to the NE via a broad stair buttress, only about 18" deep which

dies back into the main wall about 5' below the current summit.

Unfortunately this entire structure appears to be a Victorian

rebuild. The gate is protected by a portcullis, similar to the

one into the shell keep at Arundel.

Entering through the gate gives access to a spiral stair to the south

and a small chamber to the north. Beyond is the circular ground

floor room, some 30' in diameter. The room above is similar, but

octagonal and the embrasures in both are shoulder headed

(1250-1350). The chapel is above the entrance and like all below

has been ‘restored' - the peculiar trefoil doorway giving the

game away. Apparently the gate, portcullis chamber and much of

the vice and chapel and a great part of the mural gallery were rebuilt

under Sir Stephen Glynne. This level also has an internal

passageway around the interior of the wall allowing for 5 loops to

cover the vulnerable side of the tower. This bears some

similarity to the towers and walls of Caernarfon castle,

though which castle copied which is a moot point - if they did.

The idea that the similarities in style mean that Master James of St.

George must have had an input in its design is again little more than

fanciful speculation. Indeed the widespread rebuildings to the

keep makes its plan quite suspect in many respects.

On

the motte is an unusual 2 storey round keep, 61' in diameter at the

base of the plinth, with walls nearly 15' thick, but dropping to about

13' at rampart level. It is over 40' high. Entrance was

gained to the NE via a broad stair buttress, only about 18" deep which

dies back into the main wall about 5' below the current summit.

Unfortunately this entire structure appears to be a Victorian

rebuild. The gate is protected by a portcullis, similar to the

one into the shell keep at Arundel.

Entering through the gate gives access to a spiral stair to the south

and a small chamber to the north. Beyond is the circular ground

floor room, some 30' in diameter. The room above is similar, but

octagonal and the embrasures in both are shoulder headed

(1250-1350). The chapel is above the entrance and like all below

has been ‘restored' - the peculiar trefoil doorway giving the

game away. Apparently the gate, portcullis chamber and much of

the vice and chapel and a great part of the mural gallery were rebuilt

under Sir Stephen Glynne. This level also has an internal

passageway around the interior of the wall allowing for 5 loops to

cover the vulnerable side of the tower. This bears some

similarity to the towers and walls of Caernarfon castle,

though which castle copied which is a moot point - if they did.

The idea that the similarities in style mean that Master James of St.

George must have had an input in its design is again little more than

fanciful speculation. Indeed the widespread rebuildings to the

keep makes its plan quite suspect in many respects.