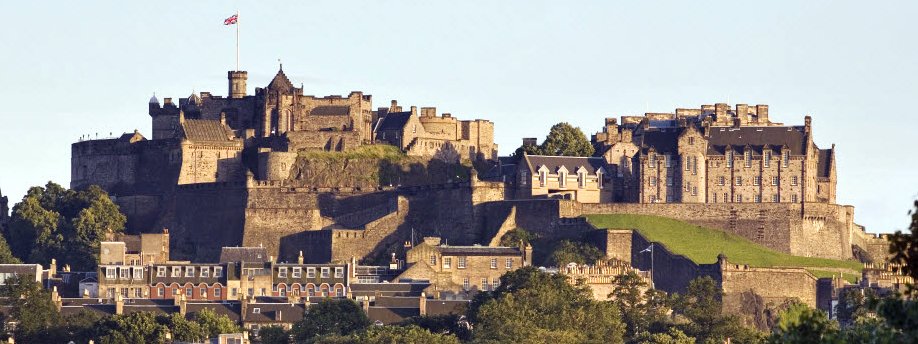

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh castle may have been the main castle of Scotland as far

back as the eleventh century, although little if any of the current castle

certainly dates to that time. The castle rock was formed 70 million years

ago, while recent archaeological excavations within the fortress have

uncovered evidence that Bronze Age man was living here 850BC.

Some 2,000 years ago, during the Iron Age, there was apparently a

settlement on its summit. Presumably the rock was still inhabited

throughout the Dark Ages, but the linking of Edinburgh with Din Eidyn is probably fantastic as is the suggestion that Catraeth - the battle on the beach - was fought at Catterick over 30 miles from the sea! Similarly the siege of Etin in the Annales of Ulster might relate to Edinburgh, but much more research into the matter is truly desirable.

Edinburgh castle may have been the main castle of Scotland as far

back as the eleventh century, although little if any of the current castle

certainly dates to that time. The castle rock was formed 70 million years

ago, while recent archaeological excavations within the fortress have

uncovered evidence that Bronze Age man was living here 850BC.

Some 2,000 years ago, during the Iron Age, there was apparently a

settlement on its summit. Presumably the rock was still inhabited

throughout the Dark Ages, but the linking of Edinburgh with Din Eidyn is probably fantastic as is the suggestion that Catraeth - the battle on the beach - was fought at Catterick over 30 miles from the sea! Similarly the siege of Etin in the Annales of Ulster might relate to Edinburgh, but much more research into the matter is truly desirable.

History

Despite the early confusion, a settlement may have stood on castle rock by 1093. A fourteenth century

chronicle states that Margaret, the wife of King Malcolm III, was

seriously ill there when she was brought news of her husband and son

having been killed at Alnwick in Northumberland - the news of which is

said to have killed her. Her biographer, working before 1112,

gives the story, but does not name the place where she lived and

died. A rectangular chapel, built on the summit of the castle

rock, is dedicated to her memory and is the oldest extant building in

Edinburgh castle. A few years after her death, in January 1107,

Malcolm and Margaret's son, King Edgar, is ‘said' by Wikipedia to

have died in the castle, though no early source, Simon Durham, Florence

Worcester, the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, or the Annales Cambriae, actually

mentions the place of his death, or indeed agree on which day in

January he died.

It would appear that King Malcolm's youngest son, King David I

(1124–1153), developed Edinburgh as a military seat, though

whether he was following in his predecessors' footsteps or not is a

moot point. Presumably his work included improvements to any

fortifications on the castle rock. At some point between 1139 and

1150, David is said to have held an assembly of nobles and churchmen at

the castle. His successor, King Malcolm IV (1153–1165),

reportedly stayed at Edinburgh more than at any other location.

His successor, King William the Lion (1165–1214), was captured at

the battle of Alnwick in 1174 and by the treaty of Falaise, made to

secure his release, he surrendered Edinburgh castle, along with those

of Berwick, Roxburgh and Stirling, to King Henry II of England

(1154-89). This is the first certain reference as Edinburgh as a

fortress. The castle was subsequently occupied by Henry's men for

twelve years. In 1186 it was returned to William as the dowry of

his Norman bride, Ermengarde Beaumont. It is apparent from this

that Edinburgh was one of the major fortresses of the relatively small

state of Scotland, which at this time occupied little more than the south-east

seaboard of what is now thought of as Scotland. To the north were the

Highlanders and Danes, while to the west lay more Highlanders, Islesmen

and Norwegians. Even to the south-west lay often hostile territory in the

form of the old ‘British' kingdom of Cumbria, by this time known

as Galloway.

A century later, on the death of King Alexander III (1249-86), the

lands owned by the Scottish kings had expanded powerfully into these

previously hostile districts. In 1251 Alexander's queen,

Margaret, the daughter of King Henry III of England, had found the

castle ‘a sad and solitary place without verdure, and by reason

of its vicinity to the sea, unwholesome'. However Alexander left

no heirs of his body and the decision of who should be the next king of

Scots passed to King Edward I of England (1272-1307) by feudal

right. Edward had assured this by asking the barons to Scotland

to pay fealty to him as their overlord and as had happened infrequently

in the relationship between the kings of England and Scotland since the

tenth century. Consequently, on 8 July 1291, Abbot Adam of

Holyrood and

Sir Richard Fraser paid the king homage in Edinburgh castle chapel

while the king was staying within the fortress.

After the revolt of the king of Scots chosen under

Edward's watchful eye, King John Balliol (1292-96), the English king

declared the kingdom of Scots forfeit to himself as feudal

overlord. In March 1296, Edward I moved his forces into Scotland

and, following the battle of Dunbar, soon took Edinburgh castle after a 3 days long bombardment. Following the siege, Edward had many

of the Scottish legal records and royal treasures moved from the castle

to England. By 1300 a large garrison of 347 men were

theoretically within the fortress. This figure included knights,

serjeants, priests, clerks and servants as well as soldiers.

On 14 March 1314, the castle finally fell to a

surprise night attack by Thomas Randolph, the first Earl of Moray. The

historically dubious narrative poem of John Barbour (d.1395), The Brus,

relates how a party of 30 men were guided by one William Francis, a

traitorous member of the garrison, who knew of a route along the north face

of the Castle Rock and a place where the wall might be scaled.

Making the difficult ascent, Randolph's men are alleged to have scaled

the wall, surprised the garrison and taken control of the

fortress. Whether the story is true or not, Robert the Bruce

immediately ordered the destruction of the castle's defences to prevent

its re-occupation. Three months later, on 24 June 1314, near

Stirling, Bruce's army defeated King Edward II (1307-27) at the battle

of Bannockburn, when that king attempted to relieve the siege of

Stirling castle.

King Robert the Bruce died in 1329. Shortly

before this he had ordered the repair of the castle chapel. After

his death, Edward Balliol (d.1364), the son of the former King John Balliol,

claimed the Scottish throne against the claim of Bruce's young son,

David Bruce. Edward invaded in 1332, destroyed the Brucian army

at Dupplin Moor and was crowned king of Scots. Here the

chronicler John Fordun (d.c.1390, and writing his chronicle between

1384 and September 1388), or his redactor, Walter Bower (d.1449), goes

astray in stating that Edward Balliol could not be king as he had legally abandoned his claim to King Edward I of England and consequently was allowed to go and live with his father, the ex King John Balliol

in France. As the English exchequer records no such agreement

and, as Balliol never met his father after his abdication and certainly

never lived with him in France, we can see how Fordun has distorted

history to suit the current political narrative of late fourteenth

century Scotland.

Regardless of more modern politics, before the year 1332 was out, King Edward Balliol

was expelled from the kingdom after the rout of Annandale. During

the summer of 1335, the Brucite Earl John Randolph of Moray (d.1346)

formed an army with William Douglas (d.1353) and met Count Guy of

Namaur (d.1336) and a relatively small force, on the Boroughmuir south

of Edinburgh. Count Guy was outnumbered and slowly fell back on

Edinburgh. There, according to Walter Bower:

They climbed the lamentable

hill where there used to be Maidens' castle of Edinburgh, which had

been demolished earlier for fear of the English. These crags they

defended courageously, killing their exhausted and injured horses, they

made a defensive wall with their bodies. And thus, surrounded and

besieged by the Scots throughout the whole night, they passed it

continuously without sleep, hungry, cold, thirsty and weary.

Exhausted and distressed with no hope of succour, in the morning

of the next day they surrendered themselves...

After this Moray was captured leading the defeated Flemings back to Berwick, but Balliol reoccupied and

refortified Edinburgh castle the same year, the works of which included 4

glass windows for St Margaret's chapel. Edinburgh remained a

Balliol stronghold until the castle was taken again by William Douglas of Hermitage castle on 17 April 1341. According to Wyntoun, Douglas' party

disguised themselves as merchants from Leith bringing supplies to the

garrison and stopped a cart in the castle gateway, preventing the gates

from closing and the portcullis from dropping. A larger force

hidden nearby rushed to join them and seized the castle. Modern

‘histories' state that the Balliol garrison of 100 men were all

killed, despite the fact that not even Wyntoun claims this.

In 1357 the treaty of Berwick brought a halt to the

wars for a while. King David II then set about rebuilding

Edinburgh castle which again became a principal seat of

government. David's tower, a new keep, was begun around 1367, and

was incomplete when David died at the castle in 1371. It was

completed by his successor, King Robert II, in the 1370s. The

remains of the tower are still partially under the present Half Moon

Battery. The keep was connected by a section of curtain wall to

the smaller Constable's Tower, a round tower built between 1375 and

1379, where the Portcullis Gate now stands. In 1384 the first

artillery piece was purchased for the castle.

In the early fifteenth century King Henry IV reached Edinburgh

castle and began a siege, but eventually withdrew, mainly due to lack

of supplies. From 1437, William Crichton was keeper of Edinburgh

castle and as chancellor sought to break the power of the

Douglases. To this end the 16 year old William Douglas, sixth earl

of Douglas, together with his younger brother David, were summoned to

the castle in November 1440. After the so-called Black Dinner had

been eaten in David's tower, both boys were summarily executed on

trumped-up charges in the presence of the 10 year old King James II

(1437–1460). Douglas' supporters subsequently besieged the

castle, inflicting damage, but not taking it. Construction and

reconstruction continued throughout this period, with the area now

known as Crown Square being laid out over various vaults in the 1430s.

By 1449 Edinburgh castle had become the home

of the Scottish artillery. Royal apartments were built, forming

the nucleus of the later palace block, and a great hall was in

existence by 1458. In 1464, access to the castle was improved

when the current approach road up the north-east side of the rock was created

to allow easier movement of the royal artillery train in and out of the

upper ward. One such gun of the era was Mons Meg, made at Mons in

Belgium and housed at Edinburgh since 1457. She was kept with the

rest of the royal guns in the castle, but her enormous bulk, weighing

in at over 6 tons, soon made her obsolete for all but ceremonial

salutes. In 1681, during a birthday salute for the duke of

Albany, later King James VII of Scotland and James II of England, her

barrel burst open and she was unceremoniously dumped beside Foog's Gate

in the castle. The restored gun can still be viewed in the castle

today. By 1474 the fortress had become the site of manufacture of

artillery and bronze guns were being cast within the castle by

1498. In 1541 the castle contained 413 guns.

In 1479, Duke Alexander Stewart of Albany was

imprisoned in David's tower for plotting against his brother, King

James III (1460–1488). He escaped by getting his guards

drunk, then lowering himself from a window on a rope. Albany fled

to France, then England, where he allied himself with King Edward

IV (d.1483). In 1482, Albany marched into Scotland with Duke Richard of

Gloucester (later King Richard III) and an English army. James

III was trapped in the castle from 22 July to 29 September 1482 until

he successfully negotiated a settlement.

A change in function of the castle began with the

new century when King James IV (1488–1513) built Holyrood house,

by the nearby abbey, as his principal Edinburgh residence. As a

result the castle's role as a royal home declined. Despite this,

James did construct another great hall at the fortress. This was

completed in the early sixteenth century before James IV was killed at the battle

of Flodden on 9 September 1513. As a consequence his regents

hastily constructed a town wall around Edinburgh and attempted to

augment the castle's defences. Robert Borthwick, the royal master

gunner of Edinburgh, and Antoine d'Arces were involved in designing new

artillery defences and fortifications in 1514, though it appears from

lack of evidence that little of the planned work was carried out.

Three years later, King James V (1513–1542), still only 5 years

old, was brought to the castle for safety. Upon his death, 25

years later, the crown passed to his week old daughter, Mary, Queen of

Scots. In the ensuing wars King Henry VIII attempted to force a

dynastic marriage on Scotland. This led to the refortification of

Edinburgh castle. New defences were added including an earthen

angle-bastion called the Spur. This was of a type known as trace

italienne and is one of the earliest examples in Britain. It may

have been designed by Migiliorino Ubaldini, an Italian engineer from

the court of Henry II of France and is said to have had the arms of

France carved on it. James V's widow, Mary of Guise, acted as

regent from 1554 until her death at the castle in 1560.

The following year, 1561, the Catholic, Mary, Queen

of Scots, the widow of King Henry II, returned from France to begin her

reign. In July 1565, the queen made an unpopular marriage with

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, and the following year, on 19 June 1566, in

a small room of the palace at Edinburgh castle, gave birth to their son

James, later to be James VI of Scotland and I England. Two years

later Darnley was murdered at Kirk o' Field and within 3 months Mary

married James Hepburn, fourth earl of Bothwell, one of the chief murder

suspects. A large proportion of the nobility rebelled, resulting

ultimately in the imprisonment and forced abdication of Mary at Lochleven castle. She escaped and fled to England, but some of the

nobility remained faithful to her cause. Edinburgh castle was

initially handed by its captain, James Balfour, to the Regent Moray,

who had forced Mary's abdication and now held power in the name of the

infant King James VI. Shortly after the battle of Langside, in

May 1568 and Mary's flight to England, Moray appointed William

Kirkcaldy of Grange as keeper of the castle.

Moray was murdered in January 1570 and next year Sir

William decided to come out openly in support of the exiled queen after

the fall of Dumbarton castle to Mary's supporters in April 1571.

Government forces under the new regent, the earl of Lennox, immediately

laid siege to the castle that May, but since the best artillery was

inside the castle, it proceeded inconclusively for two years - hence

its name - the Lang Siege. The town was unsuccessfully besieged

in May and again in October. After the regent appealed to

Elizabeth I (d.1603) a truce was declared in July 1572 by English ambassadors

which effectively abandoned the town to Lennox.

With the expiry of the truce on 1 January 1573,

Grange began bombarding the town although his supplies of powder and

shot, not to mention gunners, were running low. The king's forces

now began digging trenches around the castle, while St Margaret's well

was poisoned. By February only Edinburgh castle remained fighting

for Mary despite the water shortage within the fortress. The

garrison continued to bombard the town, killing a number of citizens

and making sorties to set fires, burning 100 houses in the town and

then firing on anyone attempting to put out the flames. In April,

a force of around 1,000 English troops, led by William Drury, arrived

in Edinburgh. They were followed by 27 cannon from Berwick, including

one that had been cast within Edinburgh castle and captured at

Flodden. The English troops built an artillery emplacement on

Castle Hill, immediately facing the east walls of the castle, and five

others to the north, south and west. By 17 May these batteries began a

bombardment. Over the next 12 days the gunners fired around 3,000 shots

at the castle. On 22 May, the south wall of David's Tower collapsed,

and the next day the Constable's Tower came down. This debris

blocked the castle entrance, as well as the Fore Well, although this

had already run dry. On 26 May, the English attacked and captured

the Spur, the outer fortification of the castle, which had been

isolated by the collapse. The following day Grange emerged from

the castle by a ladder after calling for a ceasefire to allow

negotiations for a surrender to take place. When it was made

clear that he would not be allowed to go free even if he ended the

siege, Grange resolved to continue the resistance, but the garrison

threatened to mutiny. He therefore arranged for Drury and his men

to enter the castle on 28 May, preferring to surrender to the English

rather than to Regent Morton. Edinburgh castle was handed over to

George Douglas of Parkhead, the Regent's brother, and the garrison were

allowed to go free while Grange, his brother James and two jewellers,

who had been minting coins in Mary's name inside the castle, were

hanged at the Cross in Edinburgh on 3 August.

Subsequent to the siege much of the castle was

rebuilt by Regent Morton, including the Spur, a new Half Moon Battery

and the Portcullis Gate. The Half Moon Battery, while impressive

in size, is considered by historians to have been an ineffective and

outdated artillery fortification. The battered palace block

remained unused, particularly after James VI departed to become king of

England in 1603, although some repairs had been carried out in 1584,

while in 1615–1616 more extensive repairs were undertaken in

preparation for his return visit to Scotland. The principal

external features were the three, 3 storey oriel windows on the east

facade. These faced the town and emphasised that this was a

palace rather than a castle. During his visit in 1617, James I

held court in the refurbished palace block, but still preferred to

sleep at Holyrood.

James' successor, King Charles I, visited Edinburgh

castle only once, hosting a feast in the great hall and staying the

night before his Scottish coronation in 1633 - the last occasion that a

reigning monarch resided in the castle. In 1639, in response to

Charles' attempts to impose episcopacy on the Scottish church, civil

war broke out between the royalists and the Presbyterian

Covenanters. The Covenanters, led by Alexander Leslie, captured

Edinburgh castle after a short siege, although it was restored to

Charles after the peace of Berwick in June of the same year. The

peace was short-lived, however, and the following year the Covenanters

took the castle again, this time after a three-month siege, during

which the garrison ran out of supplies. The Spur was badly

damaged, and was subsequently demolished in the 1640s.

In May 1650 the Covenanters signed the treaty of

Breda, allying themselves with the exiled Charles II against the

English Parliamentarians, who had executed Charles I the previous

year. In response to the Scots proclaiming Charles king, Oliver

Cromwell launched an invasion of Scotland, defeating the Covenanter

army at Dunbar in September. Edinburgh castle was taken after

another damaging 3 month siege. After his Restoration in 1660,

Charles II maintained a full-time standing army, part of which was

continuously maintained at the castle. Thus the medieval royal

castle was transformed into a garrison fortress until 1923.

During 1688 the Protestant William of Orange landed

in England and the more Catholic James VII of Scotland and II of

England, the last Stewart king, fled into exile. William and his

wife, Mary (James's elder daughter), were proclaimed joint sovereigns

of England, while the governor of Edinburgh castle, the duke of Gordon,

prepared the fortress for defence. The siege began in March 1689

and lasted for three months, with initially 160 men holding off

7,000. Gordon eventually surrendered on 14 June, due to dwindling

supplies and having lost 70 men during the siege. By this time

William and Mary had been offered and accepted the Scottish

Crown. Under the terms of the Acts of Union, which joined England

and Scotland in 1707, Edinburgh was one of the four Scottish castles to

be maintained and permanently garrisoned by the new British Army, the

others being Stirling, Dumbarton and Blackness.

The castle was almost taken in the first Jacobite

rising in support of James Stuart, the Old Pretender, in 1715. On

8 September, just 2 days after the rising began, a party of around

100 Jacobite Highlanders, led by Lord Drummond, attempted to scale the

walls with the assistance of members of the garrison, but the assault

failed. In 1728, General Wade reported that the castle's defences

were decayed and inadequate, and a major strengthening was carried out

into the 1730s. This saw the completion of the Argyle Battery,

Mills Mount Battery, the Low Defences and the Western Defences.

Within a few years of the completion of these works

the last military action at the castle took place during the second

Jacobite rising of 1745. The Jacobite army, under Bonnie Prince

Charlie, captured Edinburgh town without a fight in September 1745, but

the castle remained in the hands of General George Preston. After

their victory over the government army at Prestonpans on 21 September,

the Jacobites attempted to blockade the castle, which brought them

under the fire of the garrison guns. The Jacobites had no heavy

guns with which to respond so they withdrew, leaving Edinburgh to

invade England.

With no more attacks on the castle it became useful

for holding prisoners of war, although upkeep included building powder

magazines, stores, the Governor's House in 1742 and the New Barracks

(1796–1799). The use of the castle as a prison ended in

1814 after 49 prisoners of war had escaped through a hole in the south

wall. In 1818, Sir Walter Scott discovered the Crown of Scotland,

believed lost after the union of Scotland and England in 1707, in a

sealed room, now known as the Crown Room. The Honours of Scotland are

still on public display within the castle.

Description

Description

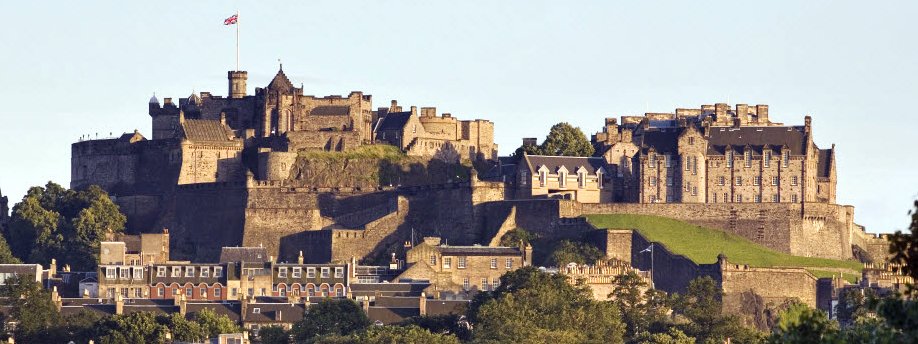

The castle stands upon the plug of an extinct volcano, which is thought

to have risen about 350 million years ago during the lower

Carboniferous period. Subsequent glacial erosion was resisted by

the basaltic dolerite, which protected the softer rock to the east,

leaving a crag and tail formation. The summit of the rock is 430'

above sea level, with rocky cliffs to the north, south and west, rising some

260' above the surrounding landscape. This means that the only

readily accessible route to the castle lies to the east, where the ridge

slopes more gently. The defensive advantage of such a site is

self-evident, but the geology of the rock also presents difficulties,

since basalt is extremely impermeable. Providing water to the

upper ward of the castle was problematic, and despite the sinking of a

92' deep well, the water supply often ran out during a drought or

siege, as occurred during the Lang Siege in 1573.

Archaeological investigation has yet to establish

when the castle rock was first used as a place of human habitation. The

fortress was initially referred to as the castle of the girls,

slavegirls, young wives, maidens, or ladies (Castellum

Puellarum). This name was in use from the time of King David I

(1124–1153) up until the sixteenth century, although its real meaning has

been lost. As can be seen from the above, the name Maidens'

castle is merely one possible translation of many. It is logical

that the early castle was contained on the highest point of the rock

and that the only approach, from the town to the east, therefore contained

the bulk of the defences and a series of fortified gates, each

physically lower down the rock tail than its predecessor as the

approach circled up around the citadel to the north via the lower and

middle ward.

In front of the castle to the east of the lower ward is

a long sloping forecourt known as the Esplanade. This was originally the sixteenth century hornwork known as The Spur. The gatehouse at the head of

the Esplanade was built only in 1888. The dry ditch that protects

this gate was only completed in its present form in 1742. Within

the lower ward the road, built by James III in 1464 for the transport

of cannon, leads upward and around to the north of the Half Moon Battery

and the Forewall Battery, to the Portcullis Gate. This was begun

by the Regent Morton after the Lang Siege of 1571–73 to replace

the destroyed round Constable's Tower. The upper parts of the

gatehouse were only completed in 1584 and these were further modified

in 1750. Just inside the gate is the Argyle Battery, overlooking

Princes Street, with Mills Mount Battery, the location of the One

O'Clock Gun, to the west. Below these is the Low Defence, while at

the base of the rock is the ruined wellhouse tower, built in 1362 to

guard St. Margaret's well. This natural spring provided an

important secondary source of water for the castle, the water being

lifted up by a crane mounted on a platform known as the Crane Bastion.

The area of the middle ward, to the north and west of the Portcullis Gate, is largely occupied by military buildings erected

after the castle became a major garrison in the early eighteenth century.

Behind these buildings is Butts Battery, named after the archery butts

formerly standing here. Below this are the Western Defences,

where a postern, named the West Sally Port, gives access to the west slope

of the rock. Entered from the west, the upper ward or citadel

occupies the highest part of the Castle Rock, and is entered via the

late seventeenth century Foog's Gate. The origin of this name is unknown,

although it was formerly known as the Foggy Gate, which may relate to

the dense sea-fogs, known as haars, which commonly affect

Edinburgh. Adjacent to the gates are the large cisterns built to

reduce the castle's dependency on well water and a former fire station,

now used as a shop.

The summit of the Castle Rock is occupied by the

supposedly twelfth century St Margaret's chapel. It is said to have been built as a

private chapel for the royal family and dedicated by King David

(d.1153) to his mother, Saint Margaret of Scotland, who is alleged to

have died in the castle in 1093. The walls would appear to be

made of at least four different builds. The oldest part would

logically be the foundations, although these walls are said to have

been built when the bedrock of the castle was lowered in the 1570s

rebuildings. This seems a questionable scenario. To the south

the foundations consist of a rubble laid red sandstone. This

rises some 8'-10' above the uneven bedrock and then transform into a

well laid ashlar, which looks quite black where it has not been

cleaned. This is the main floor of the chapel. Above the 3

lancet windows - of which only the west one seems original - is a rough

and ready rubble build where the roof has been raised. The same

styles can be seen in the short east wall which also has a single

lancet. The west wall has been much altered with a rectangular

doorway inserted and a lancet window possibly raised in height when

this was done. The north wall has been much, if not totally rebuilt

and shows a modern entrance doorway with a blocked and possibly reset

rectangular window beside it. It has been argued that the chapel

as it stands is only one portion of a large building which lay to the north. This seems likely considering the small size of the chapel and

its irregular shape. Internally there is a fine much restored

chancel arch of a twelfth century style with carved capitals and chevron

moulding. The apse shaped chancel has an original stone roof,

while that of the nave has been added later. This chapel and the

nearby church of St Mary, survived the slighting of 1314, when the

castle's defences were destroyed on the orders of Robert the

Bruce. After being used as a gunpowder store from the sixteenth century it

was restored in 1851-52.

East of the chapel, the Lang Stair leads down to the

Argyle Battery in the middle ward, where a section of a medieval

bastion can still be seen hugging the citadel rock. The east end of

the upper ward is occupied by the Forewall and Half Moon Batteries,

with Crown Square and the National War Memorial. These stands on

the site of St Mary's church to the south.

The Half Moon Battery, perhaps the most prominent feature of the

castle, was built as part of the reconstruction works supervised by the

Regent Morton between 1573 and 1588. It was built around and over

the ruins of David's Tower, two storeys of which still survive beneath

it. Some of its windows may still be seen facing out onto the

interior wall of the battery. The fourteenth century Tower was built to an

L plan, the main block being 51' by 38', with a wing measuring 21' by

18' to the west. The entrance was via a pointed arched doorway in

the inner angle, although in the sixteenth century this was filled in to make the

tower a solid rectangle. Prior to the Lang Siege, the tower was

recorded as being 60' high. The remaining portions stand up to

49' high from the rock. This is the most formidable remnant of

the medieval castle. The tower was only rediscovered during

routine maintenance work in 1912. Several rooms are still

accessible to the public, although the lower parts are generally

closed. Outside the tower, but within the battery, is a

three storey room, where large portions of the exterior wall of the

tower are still visible, showing shattered masonry caused by the

bombardment of 1573. Beside the tower, a section of the former

curtain wall was discovered. This has a single gun loop remaining

of the original six which overlooked the High Street: a recess was made

in the outer battery wall to reveal this surviving loop. Also in

1912–1913, the adjacent Fore Well was cleared and surveyed, and

was found to be 110' deep, and mostly hewn through the rock below the

castle.

South and west of David's Tower is Crown Square, also known

as Palace Yard. This was laid out in the fifteenth century during the reign

of King James III (1460-88). The foundations were formed by the

construction of a series of large stone vaults built onto the uneven

Castle Rock in the 1430s. The great hall, usually ascribed to the

reign of King James IV (1488-1513), is thought to have been completed

in the early years of the sixteenth century. It is one of only two medieval

halls in Scotland with an original hammerbeam roof. To the south of

the hall is a section of curtain wall, possibly dating back to the fourteenth century, complete with a parapet of later date.

Why not join me at Edinburgh and other Great Scottish Castles this Spring? Information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2016

Paul Martin Remfry

Description

Description Edinburgh castle may have been the main castle of Scotland as far

back as the eleventh century, although little if any of the current castle

certainly dates to that time. The castle rock was formed 70 million years

ago, while recent archaeological excavations within the fortress have

uncovered evidence that Bronze Age man was living here 850BC.

Some 2,000 years ago, during the Iron Age, there was apparently a

settlement on its summit. Presumably the rock was still inhabited

throughout the Dark Ages, but the linking of Edinburgh with Din Eidyn is probably fantastic as is the suggestion that Catraeth - the battle on the beach - was fought at Catterick over 30 miles from the sea! Similarly the siege of Etin in the Annales of Ulster might relate to Edinburgh, but much more research into the matter is truly desirable.

Edinburgh castle may have been the main castle of Scotland as far

back as the eleventh century, although little if any of the current castle

certainly dates to that time. The castle rock was formed 70 million years

ago, while recent archaeological excavations within the fortress have

uncovered evidence that Bronze Age man was living here 850BC.

Some 2,000 years ago, during the Iron Age, there was apparently a

settlement on its summit. Presumably the rock was still inhabited

throughout the Dark Ages, but the linking of Edinburgh with Din Eidyn is probably fantastic as is the suggestion that Catraeth - the battle on the beach - was fought at Catterick over 30 miles from the sea! Similarly the siege of Etin in the Annales of Ulster might relate to Edinburgh, but much more research into the matter is truly desirable. Description

Description