Of all the campaigns carried out by the Welsh in the twelfth century, that by Rhys ap Gruffydd in 1196 must rate as the most important in relation to castle studies. For it is in this campaign we get one of our earliest references to a Welsh prince using a siege train to force the surrender of a castle. There are two points to be borne in mind about this. The first is that the mention of the catapults and engines used against Painscastle in 1196 (and therefore by implication against Colwyn and Radnor) is done in such a way that suggests that this was NOT unusual. The second is the question when did it become usual for the Welsh princes to batter castles into submission rather than take them by stealth or starvation? Certainly in 1198 the Welsh Chronicler was astounded that Prince Gwenwynwyn of Powys was lax enough to besiege Painscastle 'without catapults or mangonels'. Yet Giraldus Cambrensis notes no surprise at the Welsh of Ceredigion and Rhwng Gwy a Hafren besieging Pembroke Castle by blockade alone in 1096. Obviously between these dates Welsh siege tactics had undergone a revolution. In my opinion these new methods arose as a result of the strong rule of King Henry I. Between 1100 and 1135 Henry obtained a close control over Wales, outside of Snowdonia, ruling the country through his own baronage, rather than the native princely stock. During this period of close contact and assimilation it is likely that the Welsh nobility, and largely dispossessed princes, learned the fundamentals of siege warfare both at home and in the king's Continental campaigns. This could well explain some of their successes against castles in the wars of King Stephen's reign.

The reign of Good King Richard the Lionhearted (1189-99) must have been a curious time for the inhabitants of England, for effectively they were ruled without a king. Richard, after his coronation in 1189, soon left England to go on Crusade, selling the offices of state to the highest bidder in his wake. When he finally returned on 13 March 1194, he decided it prudent to be crowned again at Winchester. He left England a second time on 12 May, never to return. No doubt it was his absence, as well as his heroic deeds, that made him one of the most popular kings of the English. Meanwhile the country was governed (or often divided) between successive justiciars and the adherents of Richard's recalcitrant brother John Lackland, Count of Mortain, soon to be King John.

Prince Rhys ap Gruffydd had slowly and determinedly built for himself a strong and vigorous principality in Deheubarth (South Wales) during the long and relatively stable reign of Henry II. At first he had fought the young Henry, but after the royal campaigns of the 1160's the two men had come to terms and Rhys had been promoted by Henry to paramountcy among the petty princes of the south. In the Great Rebellion of 1174 Rhys had besieged Tutbury castle in Staffordshire for the king and the next year had led the entire remaining native princely stock of South Wales to meet Henry at Gloucester to sort out ongoing border disputes. Although he was by no means totally subservient to the king, he was always well aware of the royal power and continually tried to keep the troubled peace with the English and Normans. All this was to change with the coming of Richard I. On his father's death, Richard immediately snubbed Rhys and through his indifference brought war and rebellion to South Wales. The English government left by Richard found itself incapable of dealing with Wales due to its own internal instabilities. As a consequence Deheubarth expanded at a remarkable rate to both the south and east, despite fitful government attempts to staunch the flow.

After Richard's return to his kingdom in 1194 a more robust government was left in place under archbishop Hubert Walter of Canterbury. It was under his auspices that the Marcher barons were urged (if they needed much urging) to undertake concerted action against the South Welsh and Powys in 1195. This led to royally sponsored building work at several castles along the frontier, viz at Cymaron, Bleddfa and possibly Mathrafal (Matefelun). The Marcher attack seems to have been organized under the auspices of the effective warrior-sheriff of Hereford, William Braose of Radnor (died 1211). William appears to have also been responsible for simultaneously overrunning Elfael and refortifying the castles of Colwyn (Colwent) and Painscastle although he was probably not present in person, for this year he retook the castle of Saint Clears in Dyfed. It therefore seems likely that it was his amazonian wife Matilda St Valery (starved to death by King John in 1210) who was responsible for this invasion, and also for 'slaughtering the Welsh at Painscastle'. This action may have given the castle its second name of Maud's Castle. It is also possible that the sieges of 1196, or 1198 may refer to this name when Maud may have still been the castellan. Regardless of this the concerted Marcher attack of 1195 probably persuaded Rhys that it was necessary to undertake another campaign in the east to support his 'nephews' of Rhwng Gwy a Hafren.

In the summer of 1196 the two Marcher lords involved in the battle, may well have been in eastern Maelienydd, consolidating their gains and perhaps also continuing the refortification of their castles in the cantref. Hugh Say had received £5 in 1195 to repair his castle of Bleddfa (Bledewach), and Roger Mortimer £20 to go towards the refortification of Cymaron (Camarun) Castle. The king also told the Marchers that it was unnecessary for them to return to Normandy for his campaigns there. Therefore, when Rhys attacked Colwyn in 1196 Mortimer and Say would probably have already been in eastern Maelienydd. The news that the castle was being attacked would have brought the Marchers into the field and made them march south to its relief. The natural route for them to take would have been through the Arran valley to the hill-fortress of Crug Eryr, and then down the main north-south route into Elfael Uwch Mynydd and Colwyn. If, however, when they reached Crug Eryr, they found that Colwyn had already been sacked and that Rhys was besieging Radnor they would have turned east, and therefore found themselves to Rhys' rear, 'without warning' and in the valley above Radnor. Thus may the prince of Deheubarth's surprise be explained. The heavy casualties too, are easily explainable. Each army was facing its base, so to the loser went annihilation. If this argument is correct it may be that the present remains of a formidable rampart blocking the valley, with its ditch facing Radnor, may mark the site of the battle.

The chronicles state that it was Rhys who attacked the Marchers. If the Marchers were to Rhys' rear then it might be expected that they would attack and count on surprise to win them the day. However, if the Welsh host was as massive as the chronicles boasted, then the more prudent commander might well have decided to entrench an easily held position in a narrow valley. If reinforcements arrived from England then Rhys would find himself trapped between the hammer and the anvil. Conversely, for the same reasons, Rhys had to break the Marcher army to survive. He therefore took the only option open to him and attacked the Marcher force with all his strength - the chronicles all dwell on this. Thus Rhys would have pursued the broken Marcher army into enemy territory where even greater slaughter could be done to them, perhaps even all the way to Painscastle, which he then proceeded to besiege with catapults and engines until it surrendered. In the meantime William Braose had invaded Ceredigion and burnt part of Cardigan, which was one of Rhys' main seats. It was probably because of this that a concord was made between the two protagonists, which resulted in Rhys leaving Painscastle in William's control, but in Rhys' peace, ie. Rhys had achieved part of his objective by returning Elfael to his theoretical control. Maelienydd, however, remained beyond his reach, for on 18 April 1197 he died, probably of the plague which was then sweeping Wales. His comrade in arms Prince Maelgwn ap Cadwallon of Maelienydd also died around the same time. Rhys' untimely death left his principality and his siege-train to the unlucky hands of his son Gruffydd and the squabbling siblings of the disintegrating principality of Deheubarth.

The campaign related above shows with some clarity that Colwyn was the castle attacked and burned by Prince Rhys in 1196 and that no attack was made on any Norman castle in relatively far off Shropshire by the Welsh of Deheubarth during 1195. The mistranslation of Colonwy for Clun some 35 miles north and east of Colwyn is obviously the cause of this. Clun castle in 1196 was in the hands of William fitz Alan (died 1210). At this time he was fighting with King Richard against the French in Normandy and he made no effort to return home as other Marchers would have done and are recorded as so doing if their Welsh castles were attacked. In the late twelfth century there is no evidence of anything other than a normal continuation of Norman rule in Clun Lordship.

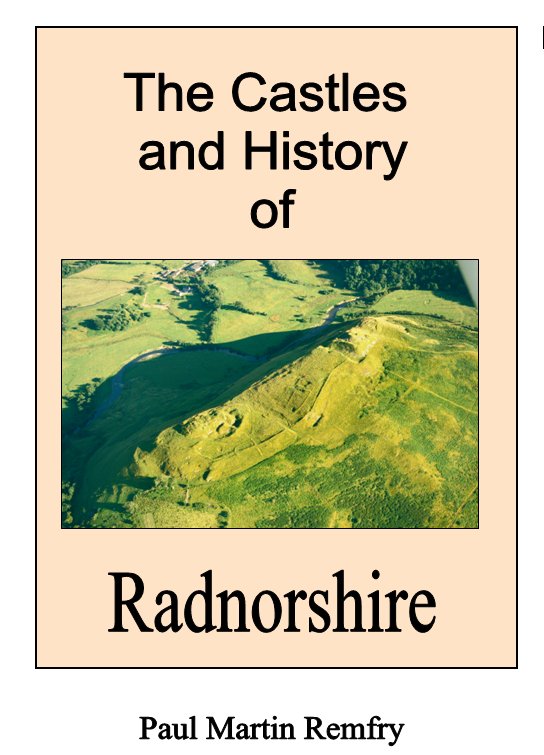

The Castles and History of Radnorshire (ISBN 1-899376-82-8) looks in great detail at New Radnor castle and the surrounding fortresses. The book consists of 309 pages of A4 and examines in greater detail the history and castles of Radnorshire and Rhwng Gwy a Hafren. Starting in the early eleventh century the book covers the age of the castles up to the Civil War of 1642-46. Each castle description is buttressed by numerous photographs and plans of the earthworks and remains where they survive. A new look is also taken at the battlefield of Pilleth and the evidence for the course of the battle is scrutinised. The book also contains genealogical family trees of the major historical Radnorshire families and a full index.

Available for £39.95.