Hywel ap Goronwy is probably one of the most overlooked kings of South Wales or Deheubarth as it was otherwise known, though in his day he was one of the most powerful. He was probably born before 1080 and was the eldest son of Goronwy ap Cadwgan ab Elystan Glodrydd. Goronwy himself died of a wasting disease in 1101, but Hywel had been active for some time before his father's death. Elystan Glodrydd before his untimely death around 1010 had carved out for himself a shadowy kingdom apparently known as Cynllibiwg and consisting primarily of the old Welsh cantrefs of Maelienydd, Elfael and Buellt. This region does not seem to have been stable and by the 1070's had been virtually extinguished by rival surrounding kings. In the late 1070's and 1080's, however, the sons and grandsons of Cadwgan ab Elystan re-established their authority. Eventually in the 1150's their surviving descendants had become known as the princes of Maelienydd and Elfael.

After the conquest of native, or pure Wales as it was otherwise known, in 1095 the Welsh began a sustained campaign of resistance. By early 1096 Hywel ap Goronwy had become one of the leaders of the Welsh revolt. That Spring he, together with Uchtryd ab Edwin and the war band of Cadwgan ap Bleddyn, laid waste the province of Penfro and strongly besieged Gerald Windsor in Pembroke castle. Unfortunately for the Welsh the wily Gerald outfoxed them and baffled, forced them to break off their siege, though they returned home with great booty. In the meantime Hywel's cousins, Gruffydd and Ifor, the sons of Idnerth ap Cadwgan, operating in Brycheiniog and Glamorgan won a great victory over a Norman force at Aber-llech in the river valley between Brecon and Swansea. For the next two years the war dragged on, but by the end of 1098 King William Rufus and his Norman baronage had to a large degree settled the 'Welsh problem' by abandoning those areas of Wales they thought untenable, viz Ceredigion, Ystrad Tywi, Powys (to its Medieval borders, not the present day ones which includes the Norman Middle Marches of Radnorshire and Breconshire) and Gwynedd above the Conway. In the remaining areas of Wales that had been conquered by the Normans the Welsh populations were not expelled, they merely exchanged their Welsh kingly rulers for Norman lords who had the same powers as their predecessors. In effect the Welsh Kings and Norman Marchers were semi-detached outliers of the kingdom of England, subservient but independent of the judicial government of the realm. The Marchers like their royal predecessors, held the right of life and death, the profits of justice and the right to form an army from their estates, theoretically for the defence of the country, but often for their own private purposes. As England became once again a country of great wealth and peace under the powerful protection of the Norman kings the professional soldiers of the Welsh and Norman Marches became of increasing importance due to the fact that these areas were increasingly the only ones to have trained and competent soldiers ready for action at the shortest notice. As the twelfth century progressed it soon became evident that most military assemblages had more than their fair quota of 'armed Welshmen'. This was never truer than in the wars of King Stephen's unfortunate reign and the question must be asked as to how were these armed Welshmen raised and what form did the Welsh community possess under Norman rule? The question however is not so easily answered.

It was in this period of enforced 'peace' that Llywelyn ap Cadwgan ab Elystan Glodrydd finally met his end, killed by the men of Brycheiniog who were unfortunately not named by the chroniclers. Were these killers Norman, English or Welsh? Probably we will never know, but Llywelyn has left us one last lingering memento. Minted at Carmarthen for William Rufus was a silver penny which bore the legend 'Llywelyn ap Cadwgan, Rex'. This is the only known coin of a Welsh king and it is intriguing that it should have been minted by a man whose descendants went on to become the leading uchelwyr of Brycheiniog and Buellt. Even more intriguing is the fact that Llywelyn's nephew, Hywel ap Goronwy, was in 1102 granted Carmarthen by King Henry I (1100-1135). Hywel also claimed the land of Brycheiniog as his rightful inheritance, although he could not substantiate his claim. No doubt Bernard Neufmarché would have been loathe to give up the land, now the bulk of his lordship of Brecon! Hywel himself came to a sticky end in 1106, but if this powerful man or his uncle had lived on as an adherent of King Henry I the history of Brycheiniog might have been very different.

The killing of William Rufus in the August of 1100 brought about a revolution in English politics. Like Rufus before him, his brother and successor, King Henry I, called on the English to assist him against the less loyal Norman leaders of the country. One result of this was the overthrow and exile from Britain of the house of Montgomery in 1102 and the removal of earls Roger Belleme and Arnulf from Shrewsbury and Pembroke respectively. This dramatic change in affairs had immediate repercussions for Wales as a whole and Brycheiniog in particular. In North Wales Gruffydd ap Cynan was accepted into the royal peace and contented himself with the kingdom of Gwynedd, abandoning the Perfeddwlad to the east. In Central Wales the collapse of the earldom of Shrewsbury released the sons of King Bleddyn of Powys from their obedience to a powerful Marcher, but it was Cadwgan ap Bleddyn who was to benefit most from this change of fortune. In the next few years he expanded his realm from Llangollen in the north to virtually Cardigan in the south. The rest of native-held Wales fell to the now virtually forgotten, but then immensely powerful, Hywel ap Goronwy of Cynllibiwg.

Hywel's activities after his failure to take Pembroke castle in 1096 have not been recorded, but it would seem likely that he helped his uncles and cousins in their war against the Normans in Brecknock. Certainly a contemporary panegyric to Hywel speaks of Brycheiniog as his rightful inheritance which by implication he was being denied possession of. What then can be said of Hywel's status after the revolt of 1102? We know from the Welsh Chronicles that during the summer Henry I had promised Iorwerth ap Bleddyn "the portion of Wales which was in the hands of the earls (Robert and Arnulf), namely Powys and Ceredigion and half Dyfed - the other portion belonging to Fitz Baldwin - together with Ystrad Tywi, Cedweli and Gower". The offer proved decisive and Iorwerth turned on his brothers Cadwgan and Maredudd who were with Earl Robert. Earls Robert and Arnulf surrendered by 29 September and left the kingdom in exile. In the meantime Iorwerth made peace with his brothers and shared his territory with them giving Cadwgan the land of Ceredigion and a portion of Powys, but consigning his other brother Maredudd to the king's prison for some unrecorded offence. Towards the end of the year Iorwerth went to Henry I and asked him to make good his promise concerning Deheubarth, but the king refused to honour his word and instead gave Pembroke to the otherwise unknown knight Sear and Ystrad Tywi, Cedweli and Gower to Hywel ap Goronwy.

Iorwerth not unnaturally opposed this division of lands which the Welsh Chronicles claimed that he had been offered. Perhaps Henry was unwilling to make Iorwerth an overmighty subject, or perhaps Iorwerth had been lacking in whatever the king had asked of him. What ever the case, King Henry in 1103 summoned Iorwerth to him at Shrewsbury "to be judged before the king's council". Iorwerth came, but he did not find concession or compromise, merely a home in the king's prison "not by law, but through might and power and violation of right". His place in Powys and Ceredigion was taken by his brother Cadwgan, while Hywel continued to prosper in Deheubarth and the remnants of Cynllibiwg.

Hywel ap Goronwy was such an important king of Wales that he had a panegyric written to him whilst he still lived. Thankfully this work has survived and is translated here in full. It is not known when this poem was written or by whom, but its survival from such an early time is rare. Probably it dates to the period Michaelmas 1102, when Henry I made his grant, and 1105 when war came again to Deheubarth. What comes below is my own poor translation of a French translation of the original Old Welsh verse. I here offer an apology to the metre and rhyme of the original composer whose work has thus been so horribly mutated into near English. I also offer thanks to my brother John Remfry who helped with the translation.

- God our pleasure, our strength, our support, our help.

- His proud chief, bulwark of chiefs, the strong breach.

- Hywel of the great perception, bulwark of Wales, with the goodness of Garway.

- Fearful for cleaving, champion to the troops, son of Goronwy.

- His anger was great, rough in the melée, misfortune to those who provoke him.

- Powerful sun, who covers a great expanse, forming a great circle.

- The land of Brycheiniog is your just property, that everybody knows.

- Here is what has been claimed, for the company of golden children, Ewias the pretty.

- The charming Ergyng, Gwent, the land of Morgannwg, the valley of the Monnow, Gower,

- Penrhyn [in Arberth], the hill of Ystrad Tywi, the dune of Garway.

- Dyfed of the two dominions, Cardigan, the circuit is complete,

- and Meirionydd, and Eifionydd and Ardudwy.

- And Llyn over there, and Aberffraw and Degannwy, Rhos and Rhufoniog,

- celebrate-known regions, prompt in violent attacks.

- Edeirnion, Ial, ready for attacks,

- prompt at war, and Dyffryn Clwyd and Nant Conway.

- The illustrious Powys and Cyfeiliog and all the rest,

- the valley of the Severn, Ceri, Dygen, pleasant and gay,

- Elfael, Buellt, the meadow of Maelienydd, which he penetrates a long way.

- Three islands adjacent to the three islands by a long crossing,

- that the Prince Hywel, victorious chief, holds in pledge.

- We will salute you as the supreme leader of the children of Noah,

- grandson of Edwin, noble king, of brilliant charm.

- Impetuous fierce dragon, danger of the great seas, as much as he can conquer,

- he has put back on, this exceptional man, around his fingers a ring of gold.

- If he was not sung about to the kings with a very large lack of discretion,

- of all the chiefs who search now for a form of tyranny,

- Hywel repels them valiantly from afar; he is better than them.

- He is worth more than them.

- They fear him and scatter themselves before his attack;

- for them the trial of tribulation and the suffering of punishment is certain.

- People of the cemetery, after illness, fever and anguish, he will not come

- as a doctor, as far as the end of the world to save them.

- Very generous Hywel, powerful and very noble, that he should be the conqueror.

- Hywel by his distinction will prevail upon my wishes.

- My desired king [my desire] in his support of gift, glory complete,

- brilliant in war, like Urien, acting with the impetuous vehemence of vultures.

- Sailor of the deep sea, conscience without fear, column of one hundred thousand [men?],

- torch of the thick shelter [trees], anchor of troops, personification of the defence of liberty.

- Handsome possessor, chief proprietor, master of all assembled,

- the best of the kings of the Occident as far as London, the most generous,

- the most broad minded, the most brave, the most handsome of the children of Adam.

- Lord of the worthy, muster of the hardy [men], drunk of the spirit of Mount Baddon,

- a very secure place, with luxurious walls, of valour/courage excessive.

- Good in matters of land, king who reigns with the fair laws

- of the race of Morgan; of Morgannwg; of Radnor, favours flow from you.

- Since the prince [?], terror of the troops, crusher of enemies.

- It is a single pleasure for foreign guests that you have been able to aid them.

- Long life to him, and a wonderful reign,

- dignity upon him, grace and riches, fortune and progeny.

So sang the bards of Deheubarth to the king of Cynllibiwg, but victory was not in the hands of Prince Hywel. Fortune had another fate for him.

The panegyric tells us much of Hywel's past and his deeds. First it is said that everybody knows that Brycheiniog belonged to him. What can be judged from this is that he was not strong enough to take it and instead had to content himself with empty boasts. He could not move Bernard Neufmarché and his knights from their well fortified castles. Secondly the poem tells us what Hywel could control, Ewias, Ergyng, Gwent, Morgannwg, Monmouth, Gower, Ystrad Tywi, Garway, both Dyfeds (though the king only granted him the eastern portion), and in Ceredigion, Cardigan. To quote the poet after this, the circuit [of Hywel's power] is complete. He then goes on to name the other illustrious districts of Wales in which Hywel holds no power. Then comes two most interesting lines in this metaphysical trip around Wales:

These lands so casually mentioned are Hywel's ancestral homelands, but now he has no rights there except for in Maelienydd and there his 'penetration' sounds far more like a warlike interruption than real tenurial power. This trip around Wales is finished with the comment about the three islands which Hywel 'holds in pledge'. These must be half Dyfed, Ystrad Tywi and Gower, pledged to him by Henry I in 1102. If Hywel thought that he was now powerful enough to reclaim his ancestral rights in the Marches of Wales he was sadly mistaken. Of Hywel's affairs in 1103 and 1104 we know nothing, but by the implication of the panegyric he probably faced conspiracies from the sons of Rhys ap Tewdwr, one of whom, Goronwy, perished in prison in 1102. Other Welsh rulers probably opposed Hywel as well. In 1105 there seems to have been a change of royal policy as during the year Richard fitz Baldwin rebuilt Rhyd y gors castle at Carmarthen and Hywel in response to this assault, attacked his Norman enemies, burning their houses and crops and ravaging the greater part of Ystrad Tywi "encompassing the land on all sides and occupying it except for the castles and their garrisons". Even more ominously the knight Sear was ejected from Pembroke by Henry I and replaced by the able and warlike Gerald Windsor.

The next year Hywel ap Goronwy was betrayed to his enemies. One Gwgan ap Meurig, Hywel's friend, councillor and foster father to one of his sons, invited him to his house one night in 1106. Gwgan then treacherously sent word to the Normans in Carmarthen telling them what he had done. At dawn an armoured host surrounded the village Hywel was staying in and raised a shout against the sleeping king. Hywel awoke and sought his sword which he had placed above his head and his spear which should have lain at his feet. Both had been removed by Gwgan. Hywel then sought out his comrades, but they had fled at the first sound of danger. Hywel too, unarmed and alone, took to his heels. In the dark he seems to have evaded his Norman enemies, but Gwgan set off after him "as he had promised the French". When Gwgan and his comrades caught up with the fugitive they half strangled him and took him back to his Norman enemies who then proceeded to behead him before taking their grisly trophy back to Carmarthen. So ended the life of King Hywel ap Goronwy.

From the point of view of Welsh history his panegyric brings forth one element of national importance. Whilst on his 'tour of Wales' the poet mentions only four places rather than areas, Penrhyn [in Arberth], Cardigan, Aberffraw and Degannwy. The significance of Penrhyn is doubtful, but it may have been at the eastern extreme of King Hywel's power. Cardigan may possibly be better read as Ceredigion, the district rather than the town which was to grow up under the protection of the castle of Aberteifi which later took the mutated name of the cantref. Aberffraw and Degannwy are in a different league however. Aberffraw had long been seen as the 'principal seat' of Wales and Degannwy had long been the fortress of Wales and is associated with the ancient King Maelgwn so hated by Gildas. Both sites are associated with power. No such inference is given to the alleged 'principal seats' of Powys and Deheubarth, Mathrafal and Dinefwr - and yet Hywel is more intimately associated with these places. The inference may well be, as the lack of evidence implies, that both these sites were only founded very late in the history of Wales. The castle at Dinefwr at least seems to owe its foundation to the Normans a few years before 1150, while Mathrafal would appear to be a Fitz Alan foundation of roughly the same era. The inference of this would seem to be that it was only in the late twelfth century that the princes of Deheubarth and Powys tried to catch up with Gwynedd and found their own royal centres, centres for which an antiquity had to be manufactured.

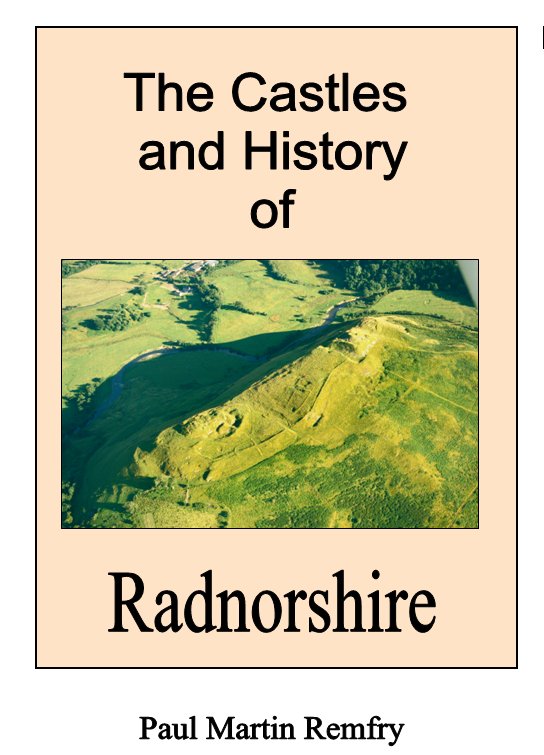

The Castles and History of Radnorshire (ISBN 1-899376-82-8) looks in great detail at New Radnor castle and the surrounding fortresses. The book consists of 309 pages of A4 and examines in greater detail the history and castles of Radnorshire and Rhwng Gwy a Hafren. Starting in the early eleventh century the book covers the age of the castles up to the Civil War of 1642-46. Each castle description is buttressed by numerous photographs and plans of the earthworks and remains where they survive. A new look is also taken at the battlefield of Pilleth and the evidence for the course of the battle is scrutinised. The book also contains genealogical family trees of the major historical Radnorshire families and a full index.

Available for £39.95.

Copyright©1994-2007 Paul Martin Remfry