The modern perception of Welsh History in the Norman period has always tended to be Gwyneddcentric. By this I mean that the political history of Wales has generally been seen as the struggle by the princes of North Wales for supremacy amongst the Welsh speakers of this corner of Britain. For them the crowning achievement of this aim was recognition of that paramount position by the English Crown. In fact since the death of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn in 1064 Venedotian (the inhabitants of Gwynedd) hegemony had only been achieved under Llywelyn Fawr in the period 1217 to 1240 and Llywelyn ap Gruffydd in the period 1263 to 1276. Outside of these two brief episodes between the Norman Conquest of England in October 1066 and the collapse of independent Gwynedd in the spring of 1283 the Welsh as a distinct race with their own speech and culture were far more likely to turn to their own local lords (Anglo/Norman and Welsh), princes and kings rather than to the lords of Aberffraw and Snowdon for protection and advancement. It is only our modern era which tries to neatly compartmentalise Welsh History into one of 'the growth of Gwynedd' into a nation state during the Middle Ages.

A study of Wales in the twelfth century soon shows that there were four competing Welsh 'kingdoms' striving for dominance in this isolated, mountainous and generally poor region, viz Gwynedd, Deheubarth, Powys and Cynllibiwg. By the end of the twelfth century all four kingdoms had been effectively destroyed, either by internal feud or external conquest, or even by a mixture of both. Indeed it is arguable that the strongest 'kingdom' had been that of Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth (d.1197) who had profited from the problems of his more easterly neighbours of Powys and Cynllibiwg as well from the weakness of his traditional Norman foes.

The kingdom of Cynllibiwg has suffered more from scholarly neglect than its contemporaries and indeed it was only recently 'rediscovered' by a researcher who put together the two pieces of the jigsaw which said that Calcebuef was a corrupt Domesday Book (1086) form of the old kingdom of Kenthlebiac, or as it was also known in the time of King Rhys ab Owain (k.1078) Inter Sabrinam et Wayam. In English this would translate to the land 'between the Rivers Severn and Wye'. In the late twelfth century Giraldus Cambrensis knew this land as Rhwng Gwy a Hafren - Between the Rivers Wye and Severn. The old name of Cynllibiwg, mentioned by Nennius in the early sixth century as Cinlipiuc or Cinloipiauc, had apparently already been forgotten by the 1190's. The end for the unstable Domesday kingdom of Calcebuef came in 1093 when it was carved up by Norman forces led by Earl Roger of Shrewsbury, Ralph Mortimer [lord of Wigmore], Ralph Tosny [lord of Clifford] and Philip Braose [lord of Radnor]. That might well have been the end of the story if it had not been for the collapse of Norman authority in Wales brought about by the death of King Henry I in December 1135.

The descendants of the old kings of Cynllibiwg immediately fomented a rebellion and, with Angevin aid, had by 1148 expelled the Mortimers and their royalist allies from most of the lands between the Wye and Severn, even if it had been at the cost of the death in battle or by treachery of at least five of their princely numbers, viz Hywel, Cadwgan and Maredudd ap Madog, Hoeddlyw ap Cadwgan and Rhys ap Hywel. With the accession of King Henry II in late 1154 only two brothers remained as princes between the two great rivers, Cadwallon ap Madog and his younger brother Einion Clud. Cadwallon had seisin of the larger and richer cantref (roughly equivalent to an English shire) of Maelienydd and Einion the more southerly and eastern 'mountainous land of Elfael'. Within these lands lay four major castles, Dinieithon and Cymaron built by the Mortimers to dominate Maelienydd, together with Glan Edw (Colwyn) and Painscastle built by the Tosnys and Pain Fitz John to dominate Elfael. The same was true of all native held Wales; what the English legal profession called pura Wallia, or that part of Wales that was administered by its own lords, rather than by Normans. What then became of these Norman castles? Many it has to be said were left destroyed, but others were certainly rebuilt by Welsh lords and their descendants who had trained in the armies of Henry I and knew well the power of the Norman fighting methods. Welsh distrust of castles lay not in their fear of new technology, but in their inability to master the discipline of castle-guard. Welsh castles fell repeatedly to the Normans, not so much through direct assault, but through lack of effective resistance. Again and again, when threatened Welsh garrisons would abandon their castles for the manoeuvrability of the open field. Llywelyn Fawr in particular preferred to dismantle his border castles and Llywelyn ap Gruffydd was to generally copy this policy.

In the Middle March of Wales, as Cynllibiwg was known to the Normans, the Welsh do not appear to have adopted this policy. For the two major castles of Elfael we have little solid fact as to their condition and fate. In 1195 when Braose forces re-occupied the southern commote of the cantref they seem to have rebuilt Painscastle primarily in wood. Despite this it withstood sieges in 1196 and 1198. In 1208 it was seized without opposition by King John and may have been granted to Iorwerth Clud, one of the princely heirs of Einion Clud. In 1215 Gwallter Clud, another son of Einion, was granted the castle by the Braoses as long as he could take it from its royal garrison. In 1216 the castle was still in Gwallter's hands when he changed sides and joined King John at Hay on Wye in a campaign aimed against Reginald Braose. Gwallter was still powerful, if not predominant in 1223, even if he did now hold the region as the vassal of Reginald! When in 1231 King Henry III came to the fortress he began to magnificently rebuild 'the wooden parts' of Painscastle in mortar and lime. This might suggest that Gwallter had continued with the upkeep of this great Marcher castle. The same can be suggested of Cadwallon ap Madog, Gwallter's much more powerful uncle.

In 1165 Cadwallon and Einion Clud had combined forces and marched with the rest of independent Wales to join the massed Welsh army under the leadership of Owain Gwynedd at Corwen. Here, through the intervention of thoroughly inclement weather, they had managed to humble the great army of Henry II. In 1175, dignified by the titles of ‘princes of Wales’, these two brothers had journeyed to Gloucester with many of their compatriots of South Wales. Here the brothers were recorded second only to the great Rhys ap Gruffydd and after them came the mass of other 'princes' of South Wales, viz Einion ap Rhys of Gwrtheyrnion, Morgan ap Caradog ab Iestyn of Glamorgan, Gruffydd ab Ifor ap Meurig of Senghennydd, Iorwerth ab Owain of Caerleon and Seisyll ap Dyfnwal of Upper Gwent. Not since the Christmas celebrations at Westminster in 1097 had so many independent Welsh 'kings' been recorded as attending a king of England. The positioning of these two men in the chronicle again demonstrates their power as inferior to that of Rhys, but superior to that of the lesser princes of single cantrefs and in some cases commotes (more like an English hundred).

Two years later Einion Clud met an untimely end, probably returning from Rhys ap Gruffydd's 'eisteddfod' at Cardigan over Christmas 1176. With his brother out of the way Cadwallon then annexed Elfael and added it to his domain which now included all the land between the rivers Severn and Wye. In August 1176 Cadwallon founded a new abbey at Cwmhir and to it he granted many lands in his domain. These spread from the forests south of Montgomery to the headwaters of the Severn in the old kingdom of Arwystli, then across to the Wye and down that great river to Clifford castle on the bounds of present-day Herefordshire. This vast 'principality' is confirmed by the land grants of Cadwallon and Einion and their descendants. What then can history and archaeology say of this 'principality'? When Cadwallon went to see Henry II at Geddington in Oxfordshire in 1177 he was recorded by a contemporary English chronicler as king of Elfael (Rex Delwain). An English royal official later copying this work substituted this 'title' with the phrase Cadwallon ruler of Elfael (Cadewalanos regulus de Delvain). It is also interesting to note his recognition and order of the rulers of Wales who accompanied Cadwallon. First in the list was king/ruler Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth, then came Dafydd ab Owain, king of a very shrunken domain in Gwynedd, then Cadwallon and finally, with no recorded titles, Owain Cyfeiliog, Gruffydd of Bromfield and Madog ab Iorwerth Goch of the now totally disintegrated 'kingdom' of Powys. The inference as to who were the most powerful men in Wales is clear, three kings or rulers of the three current major divisions of Wales and then three men who ruled the fragments of the fourth. Finally came 'the other nobles of Wales'. The power of these first three men was truly the leading force of Wales. This is again emphasised by the charters of Dafydd ap Owain. Repeatedly in charters to both English and Welsh religious establishments he used the title 'king'. He was also married to Emma the niece of King Henry II.

Rhys ap Gruffydd had for the 'capital' of this realm the great castle of Cardigan and this was further buttressed by major castles at Dinefwr, Llandovery, Aberystwyth, Nevern and Rhaeadr-gwy. Other castles fluctuated in and out of his control. In north Wales, Dafydd, after being ousted from Anglesey and his princely castle at Caernarfon, was left with his main seat at Rhuddlan castle and other strongholds at Degannwy and Basingwerk as well as possibly Pentrefoelas. What then of Cadwallon in the east? Royal records show that after his assassination on 22 September 1179 Ranulf Poer the sheriff of Hereford seized Cymaron castle for the Crown. This had most likely occurred as Cadwallon, a tenant in chief, had died greatly in debt to the king. From this we might assume that Cymaron was the caput of Cadwallon's principality, or that this castle was all the sheriff could manage to get his hands on in the increasingly turbulent and restless Middle March. It has previously been argued that Cymaron castle was garrisoned by the Crown throughout the reign of Henry II under the corrupt name Caperon. This is without doubt an error and the pipe rolls undoubtedly record a payment to a man called Caperoni who was gatekeeper at Hereford castle. Indeed at the end of Henry II's reign and into the reign of Richard I the payments continued to the widow of the now defunct hereditary gatekeeper! This error aside Cymaron castle remained in the hands of the sheriff until it was lost along with Dingestow and Radnor castle after the disastrous defeat and death of the sheriff in battle at Dingestow during 1182. Cymaron was then once more held by the princes of Maelienydd, this time in the form of Maelgwn ap Cadwallon and his brothers, until, according to the Welsh Chronicle, Roger Mortimer came in 1195 and drove them away, refortifying the castle for himself.

If it can be assumed from the above that Cadwallon held one castle in eastern Maelienydd can it also be argued that he held others? Two obvious choices would be Tomen Buddugre high above the River Eithon near Llanddewi Ystradenny and Castell Crug Eryr blocking the mountain pass into Maelienydd west of Radnor. That Crug Eryr castle belonged to the princes of Maelienydd is strengthened by Prince Maelgwn greeting the archbishop of Canterbury here in March 1188. Its name, the Eagle's mount, is also interesting for in the death lament to Cadwallon ap Madog eagles play a strong symbolic role when describing 'the renowned possessor of Cymaron' or the 'chief lord over the prosperous land of Dinieithon'. Finally Cadwallon's three sons, like three eaglets, are called upon to avenge their father. Were the eaglets waiting in the eagle's mount? If this evidence suggests that Crug Eryr was a castle of Cadwallon there is nothing but the style and position of Buddugre to indicate this castle as a Welsh foundation. Lying high on a hill top, with a natural, possibly defensive town enclosure below, it must be classified without further information as Welsh. To the north of the motte away from the castle bailey is a rectangular crop mark, in a shallow ridge joining the castle to the main hills to the north. Was this foundation the llys of Cadwallon's capital of the principality of Maelienydd or simply the site of a Victorian barn? Whatever the case the castle lies in the heart of the kingdom that once belonged to the now greatly overlooked King Cadwallon ap Madog.

For more information on the princes of Cynllibiwg purchase either A Political History of Abbey Cwmhir, 1176 to 1282 for the later history of the province or....

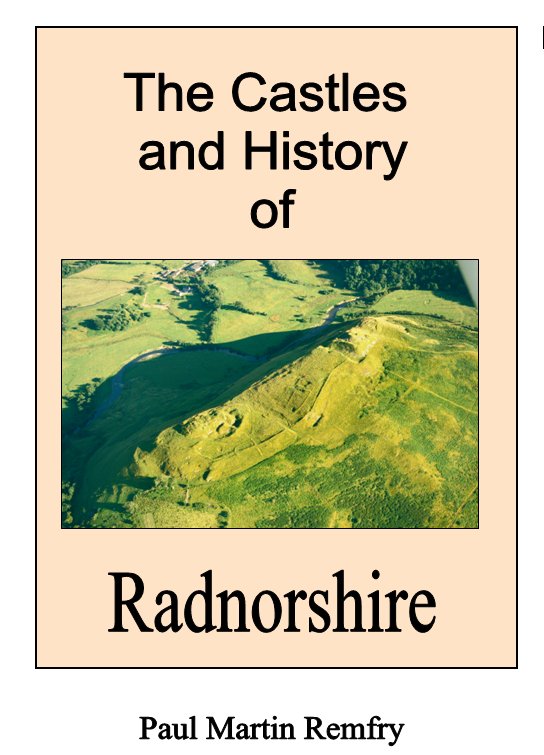

The Castles and History of Radnorshire (ISBN 1-899376-82-8) looks in great detail at Cynllibwig and Rhwng Gwy a Hafren. This book consists of 309 pages of A4 and examines in greater detail the history and castles of Radnorshire and Rhwng Gwy a Hafren. Starting in the early eleventh century the book covers the age of the castles up to the Civil War of 1642-46. Each castle description is buttressed by numerous photographs and plans of the earthworks and remains where they survive. A new look is also taken at the battlefield of Pilleth and the evidence for the course of the battle is scrutinised. The book also contains genealogical family trees of the major historical Radnorshire families and a full index.

Available for £39.95.

Copyright©1994-2007 Paul Martin Remfry