What Are Castles?

|

|

|

Brecon Castle Hall and Tower |

From the introduction to "The History of Breconshire's Castles"

In the early Medieval period in Wales and the border up

to 1282, castles in the true sense of the word, were for defence. Other

buildings more like country houses were built where the primary function was

living accommodation. Not surprisingly these lightly fortified houses were

built away from the dangerous frontiers. Obviously such distinction between

fortresses and fortified houses still existed though now it is often difficult

to tell what was the difference then. Today it is possible, indeed easy to

distinguish between a country mansion and a country cottage. However the

differences between a converted farm house and a small mansion might not be so

easy to define. The same is true with castles. They were all individual

expressions of ideas. The word castle covers a broad spectrum of structures.

This is as true now as it was then. One man's castle was another man's home!

It is noticeable too that in the Domesday Book there are references to

enigmatic fortified houses as well as to castles. Such a distinction was

obviously as valid and as dubious then as it is now.

Castles were not built to any pre-conceived rigid plan as Roman forts once were, rather they took advantage of any existing defensive features. They are often found at the end of ridges, on hill tops, at the junction of rivers or in marshy ground, all of which offered immediate advantages to the defender. Once the position had been chosen, elements were added to make the defensive attributes of the site greater. A large ditch might be dug and powerful ramparts built with the resultant spoil. Often a huge mound of earth called a motte would be made to dominate the area. Timber works might be built on or in these earthen defences, sometimes a palisade round the edge of the ditch and on top of the rampart. Then a wooden tower might be built on or, in several cases, within the motte.

|

| Brecon Castle tower |

When it came to castles proper, the defensive quality of the building was paramount to a lord, his splendour in residence came second. In the early days lords were itinerant, moving from place to place with their increasingly large retinues and consuming the foodstuffs of the district at, for the local populace, an alarming rate. A lord could not stay in one place simply because of the cost to the local community. He would literally eat them out of house and home. Loyalty to the lord, especially in the early days, was strictly personal and if the lord did not show his face to his vassals often enough they could turn to another lord for protection and advancement. This problem was especially rife in the Marches of Wales when often several barons, Norman and Welsh, claimed the same piece of land.

The castles of Breconshire were primarily fighting castles. Few were built with comfort or accommodation in mind. Their purpose was to keep the flag flying whilst massive military forces were built up to destroy the attackers. In the Middle Ages most battles were not just random clashes between armed bands, almost inevitably they were clashes between besiegers and those attempting to relieve the besieged. The bloody campaigns that will be related below clearly show the changing military designs over two hundred years of nearly continuous warfare, when Breconshire was part of the Middle March of Wales.

|

|

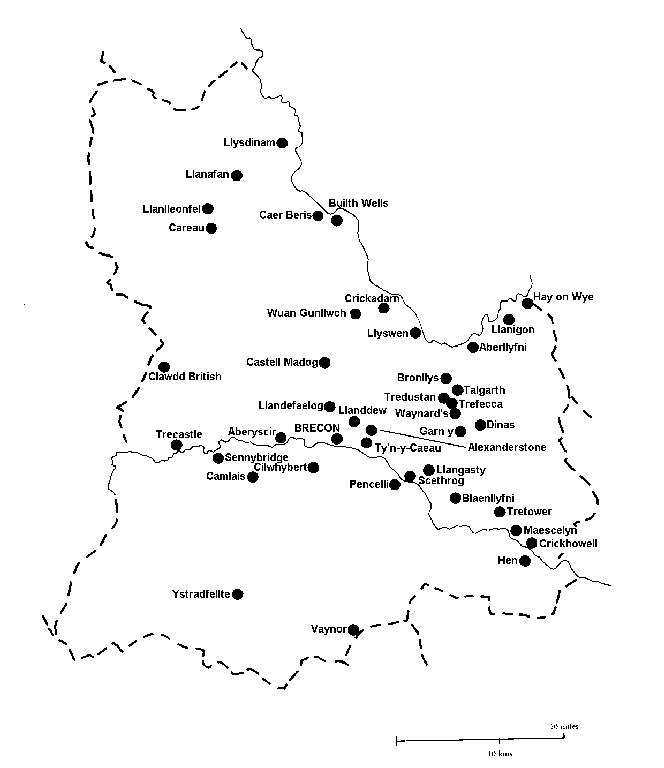

The castles of Breconshire |

Many castles in Breconshire are of the type called motte and bailey, that is the large steep-sided conical mound with a defensive enclosure at its base. Later, or sometimes simultaneously with these constructions, stone elements were added to the castle. Sometimes a stone gateway, the most vulnerable part of the castle, sometimes a stone tower on or in the motte and nearly always at some time in a castle's life, wooden or stone accommodation was added in the bailey. The lack of such accommodation could well prove disastrous for the garrison, especially in a bleak winter such as that at Cefnllys Castle in Radnorshire during the campaign of 1262.

The main purpose of the castle can therefore be seen to have been military. Accommodation on the frontier was of secondary interest to self-preservation, as it has always been. It was only later, with the pacification of a district, that the castle was abandoned, for new, cheaper and more homelike surroundings, for it was often far too costly and difficult to convert the cold, dark and forbidding fortresses into comfortable country residences. This is why we often find a manor house or farm adjacent to a castle ruin. But the old castle was still there just in case - a kind of insurance policy. This is superbly illustrated in Breconshire by the fine examples of Tretower Castle and Court, standing within easy distance of one another. The castle itself is interesting, having in its life changed from castle to home to castle again. In 1403 the Berkeley owners of the court refurbished the old castle walls in hope of self-preservation as well as obedience to the royal writ. The castle, itself already well over three hundred years of age was still fulfilling its original military purpose. The desperate actions of the castle's defenders would have been echoed on numerous other occasions in other unrecorded sometimes hopeless actions down through the centuries.

The Castles of Breconshire is currently out of print, but a new version is being planned.

Copyright©1994-2004 Paul Martin Remfry