The castle had been commenced by

Bernard Neufmarché soon before 17 April 1093 when King Rhys ap

Tewdwr of Deheubarth was killed at the battle of Brecon.

From the first the castle seems to have incorporated a town

defence. After Neufmarché fell from favour during the reign of King Henry I, the castle

passed to the Gloucester family who soon became earls of

Hereford. From them the castle and barony passed to the hands of

the Braose family in the same manner as Abergavenny towards the end of 1165.

The castle had been commenced by

Bernard Neufmarché soon before 17 April 1093 when King Rhys ap

Tewdwr of Deheubarth was killed at the battle of Brecon.

From the first the castle seems to have incorporated a town

defence. After Neufmarché fell from favour during the reign of King Henry I, the castle

passed to the Gloucester family who soon became earls of

Hereford. From them the castle and barony passed to the hands of

the Braose family in the same manner as Abergavenny towards the end of 1165.The castle may have been attacked in 1168 by Prince Rhys ap Gruffydd (d.1197) and was occupied by royal forces in 1208 after the failed Braose rebellion. In 1215 the two remaining Braose brothers retook the castle and in 1217 the townsmen and Braose garrison successfully bought off an attack by Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. After the killing of William Braose in May 1230, Llywelyn returned in 1231 and 1233, but on neither occasion succeeded in penetrating the castle defences. In the subsequent dismemberment of the Braose holdings the lordship of Brecon passed to the Bohun earls of Hereford.

In early 1263 the castle was transferred from the lordship of Humphrey Bohun (d.1265) to the keeping of Roger Mortimer of Wigmore. Mortimer seems to have immediately suffered problems of loyalty with the men of Brecon who possibly resented the loss of their Bohun lord. As a consequence of this it would seem that Roger wrote to the king concerning Brecon castle and the intransigence of the inhabitants. A little time later Roger was wounded in battle and his garrison 'shamefully surrendered' to Llywelyn about the end of May. An apparently successful attempt was made on the castle by the Lord Edward in June/July 1265 when Llywelyn's castle beyond Brecon fell, though the castle changed hands yet again soon after. The status of the castle was uncertain when Mortimer was decisively defeated outside the town on 15 May 1266, but was certainly lost to him after this action. Prince Llywelyn then spent some considerable effort on ensuring the safety of the castle and it may have changed hands 3 times in 1273, with Humphrey Bohun Junior (d.1298) finally obtaining control of the castle and by 1277 the whole lordship.

The castle may have been attacked in 1295 and was a mustering point for the rebels of 1321, falling undefended to royalist forces soon afterwards. In 1403 a siege of the castle was broken by the sheriff of Hereford and in 1483 the castle saw itself as the muster point for yet another abortive rebellion. Soon afterwards it was totally abandoned.

Description

The castle lies north-west of the River Honddu where it runs south into the eastwards flowing River Usk. The area enclosed by the defences seems to have been about 400' north to south by 300' east to west at its northern side. The southern end of the site with the small ward was only about 200' across. It is now difficult to judge these distances as the site has been much disturbed, especially to the west. The most prominent part of the castle was the great motte. This can now be easily missed, for although it is currently about 50' high, it is also densely wooded and lying as it does in a private garden behind a high wall, it is almost invisible. There are the remains of strong ramparts running up the motte top from west and south, the motte forming the north-east corner of the defences above the scarp down to the river Honddu. There must once have been a substantial ditch to the north, but this has since been filled in. The defences to the west have gone, but the scarp above the road called The Avenue probably mark the line of a curtain, while the road may occupy the site of the ditch. To the south there was a small outer ward in the heart shaped junction of the rivers. Just north of this lie the remains of the castle hall and some towers.

On

the motte top are the remnants of a shell keep, now known as Ely's

tower. The keep dimensions are some 75' E-W by 55' N-"

internally. Of the shell keep much has been disturbed by later

landscaping which also may have been responsible for the addition of

the rampart running up the motte from the west. This was dug into

in the 1950s when building stone and good-quality cement were found

lying loose. This may imply that the bank consists of rubble

piled up during eighteenth or nineteenth century landscaping. The

shell keep itself appears to have consisted of several 15' long

external lengths of walling, probably forming an irregular decagonal or

dodecagonal keep. Now the main feature of the masonry is a small

projecting, externally pentagonal, turret which has a deeply spurred

base and old red sandstone quoins. The rest of the untidy

rubble-built walls appear to be of local grey sandstones.

Internally the turret houses a small barrel vaulted room with a small

light to the east. Its purpose is debatable, but it could have

made a ground floor bedroom, perhaps similar to those found in the

turrets of the great tower at Clun castle, Shropshire.

On

the motte top are the remnants of a shell keep, now known as Ely's

tower. The keep dimensions are some 75' E-W by 55' N-"

internally. Of the shell keep much has been disturbed by later

landscaping which also may have been responsible for the addition of

the rampart running up the motte from the west. This was dug into

in the 1950s when building stone and good-quality cement were found

lying loose. This may imply that the bank consists of rubble

piled up during eighteenth or nineteenth century landscaping. The

shell keep itself appears to have consisted of several 15' long

external lengths of walling, probably forming an irregular decagonal or

dodecagonal keep. Now the main feature of the masonry is a small

projecting, externally pentagonal, turret which has a deeply spurred

base and old red sandstone quoins. The rest of the untidy

rubble-built walls appear to be of local grey sandstones.

Internally the turret houses a small barrel vaulted room with a small

light to the east. Its purpose is debatable, but it could have

made a ground floor bedroom, perhaps similar to those found in the

turrets of the great tower at Clun castle, Shropshire.From the turret one wall continues to the north, while four sections of wall are still traceable running south, but slowly turning east. These walls have at least 6' high plinths which can be seen to be stepped at the bottom on the south front of the enceinte. Stepped plinths tend to be of an early date and it seems likely that the turret, with its sandstone quoins, is additional to the original polygonal keep. There are no string courses in the structure and this again suggests an early date. At the western end of the remaining walls two parallel slots for timber reinforcement in the thickness of the curtain can still be made out.

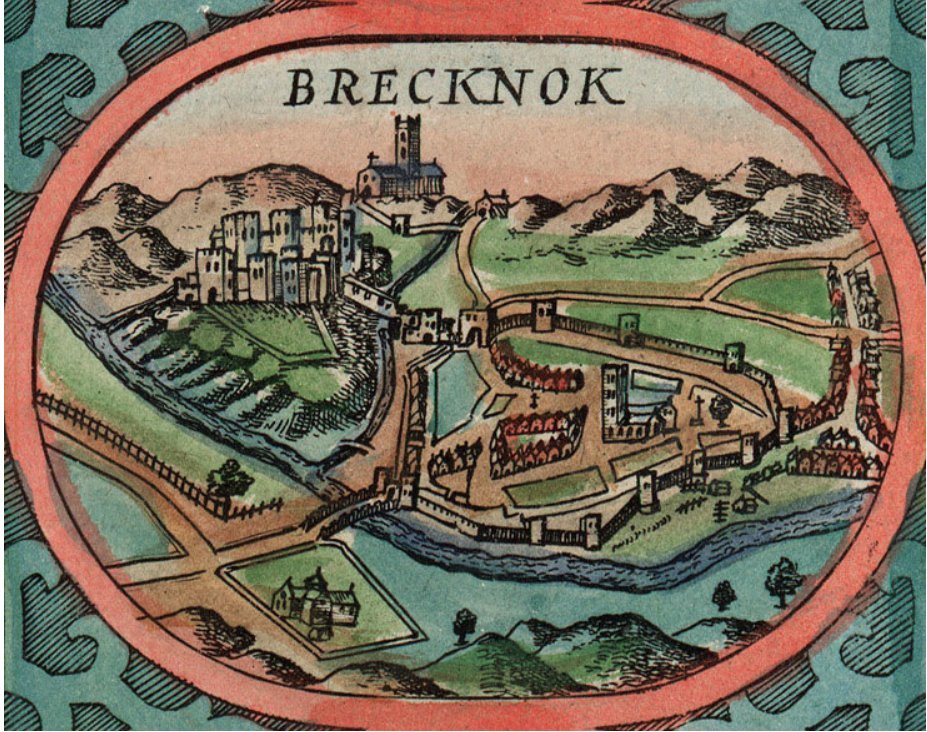

In

1610 John Speed drew a picture of the castle to illustrate his map book

of the British Isles. This shows the castle occupying the

northern portion of an heart shaped mound in the crook of land between

the rivers Usk and Honddu. The drawing does bear a certain

resemblance to the current ruins, but some points have to be raised

before describing what Speed recorded. In the background is

Brecon priory on the other side of the valley to the castle. This

bears some resemblance to the current structure, but the tower shown is

twice the height of the present tower and no aisles are shown. As

the church had aisles since the fourteenth century at the latest and

the tower shows no sign of having been lowered, the evidence of Speed's

map must be suspect. That said it would seem likely that the plan

of the town and castle given is correct, for certainly what remains can

be loosely matched to his drawing.

In

1610 John Speed drew a picture of the castle to illustrate his map book

of the British Isles. This shows the castle occupying the

northern portion of an heart shaped mound in the crook of land between

the rivers Usk and Honddu. The drawing does bear a certain

resemblance to the current ruins, but some points have to be raised

before describing what Speed recorded. In the background is

Brecon priory on the other side of the valley to the castle. This

bears some resemblance to the current structure, but the tower shown is

twice the height of the present tower and no aisles are shown. As

the church had aisles since the fourteenth century at the latest and

the tower shows no sign of having been lowered, the evidence of Speed's

map must be suspect. That said it would seem likely that the plan

of the town and castle given is correct, for certainly what remains can

be loosely matched to his drawing.According to Speed access to the town to the east was gained from the castle by a fortified stone bridge across the Honddu. This lay centrally between the surviving east towers of the hall block and the keep and consisted of a battlemented wall running down the scarp from the castle to the river. The bridge itself seems to have had a central tower, making it possibly similar to the surviving medieval Monmouth bridge, 32 miles SE of Brecon. The curtain from the bridge led to what may have been a rectangular gate tower, possibly similar to the one at Hay on Wye, which was later converted into a keep. From here the curtain ran southwards towards the surviving remains in the Castle Hotel site which consists of a three-quarters round tower adjoining a large hall block. Onto this was tacked a later polygonal latrine tower. From here the enceinte ran westwards via a rectangular tower to a large rectangular tower with a south facing gate that gave entrance to the lower ward which appears to have consisted of simply a low wall running along the scarp up from the rivers Honddu and Usk. This tower may have had a barbican to the external west side. North of this was another large square tower which marked the north-western extent of the castle. The curtain then ran back up the motte, with another rectangular tower half way to the keep. It is noteworthy that the keep at Brecon is not shown standing on a motte, but the keep drawn at Pembroke by Speed is seen standing on a motte, even though there was never one there! Obviously a certain degree of artistic licence has been employed in the drawing of this site and several others. Quite likely these drawings were not done on site and probably used memory for their conception rather than a draughtsman's eye.

Several sketches from the eighteenth century largely use Buck's mid eighteenth century print. This shows the Honddu bridge somewhat similar to the one that can be seen today, but with fine Romanesque arches of 2 orders, rather than the poor quality ones seen today. Currently visible are the lower portions of a ‘buttress' on the castle side. This may mark the base of the tower shown in buck's print. Above this was a simple hole in the wall Romanesque gateway that led into the castle. The keep on the motte in the sketches survive better than today and appears to have had a rectangular turret to the SE of which there is no trace today. Possibly this is artistic licence.

Buck's print clearly shows the hall block in its premodernisation form. The polygonal tower is drawn as more circular, while there appears to have been a doorway into the three quarters round tower at ground level. There is no trace of such an opening now, although the front of the latrine tower is still devoid of apertures. The south wall of the hall is remarkably similar to what remains today, although one window is missing on first floor level and the apertures displayed are much bigger than today, while the second floor windows are in reality more evenly spaced than those displayed in Buck. The split batter is shown in Buck and clearly matches current reality. However, not a battlement is to be seen in Buck and quite clearly the hall block summit has been totally reconstructed since his day. Indeed no battlements appear on any sketch of the castle before 1816. Obviously the whole has been heavily restored/rebuilt since then.

After 1809 the Morgans of Tredegar Park bought the castle and spent large amounts of money repairing the house attached to the present ruins and converting it into the Castle Hotel. This work had been completed by 1865. Excavation has uncovered some of the ground floor of the hall which had 5 lights facing south in a wall that was some 9' thick. The D shaped drum turret at the SE corner was almost 15' deep being totally solid at this level. The less vulnerable north, east and west walls were only about 7' thick, but very little of these now remain. The current east wall of the D shaped turret has been massively rebuilt into a rectangular tower that is totally modern as the old sketches of the site clearly show.

The nearest equivalent to Brecon castle hall would appear to be that at Haverfordwest castle, which was also held by the Bohun family from 1247 to 1289, with a period of royal control between 1265 and 1274. Judging from this it would seem possible that the hall blocks at both castles were built in the mid thirteenth century. Certainly the small D shaped tower bears some resemblance to southern towers of Skenfrith castle which were built 1219-22.

At

Brecon the apertures of the hall block towers are unusual.

As far as can be seen, all the windows in the hall itself appear

Victorian rebuilds of dubious antiquity. Those in the towers are

likewise suspect, but although possibly reset, some jambs appear

original. The rounded front of the turret supports loops at 3

levels in its under 4' thick wall. After a slight batter, topped

with a roll moulded string course, come 2 obviously Victorian loops, a

lancet window to the south and a precision cut crossbow loop to the

east. These are topped by crude relieving arches. This

layout is repeated in the level above, but here both apertures have the

appearance of true medieval loops. This layout is repeated on the

top floor, although the window appears more rebuilt. Internally

the embrasures of the loops are far too close together for this to have

been an original medieval layout. The eastern facing crossbow

loops are unusual in being set in the junction of the turret and

curtain. Such loops would have been of limited military use

without embrasures behind them to allow a stable fighting platform,

while their being twinned with windows makes the layout most

uncomfortable and unmilitary. Grosmont castle

has ground level simple crossbow loops like this, but those at Brecon

are powerful loops, with central sighting slits, but no basal oilets at

base or summit. The fact that the Victorians have copied this

style in their 2 replacement loops would suggest that the style is

original, as too would their crude representation in some of the

eighteenth century sketches of the site. As these loops exist to

the east, it is unusual that they do not to the south where the west

wall of the polygonal latrine turret was later added. However, as

this section of the wall has been smashed through to allow access to

the polygonal latrine turret, it is possible that they once existed,

although it seems far more likely that the surviving eastern crossbow

loops are later aesthetic additions, perhaps being added when the

corner loops were replaced with windows. Certainly E. Sparrow's

1786 sketch shows just one large Romanesque lower window with two

crossbow loops above where the lancets are now and no loops at all in

the junction which is shown as largely collapsed. This seems the

most likely reconstruction, that the 3 junction crossbow loops are

Victorian additions with the upper 2 being made of the pieces taken

from the neighbouring loops when the 2 lancets replaced them.

At

Brecon the apertures of the hall block towers are unusual.

As far as can be seen, all the windows in the hall itself appear

Victorian rebuilds of dubious antiquity. Those in the towers are

likewise suspect, but although possibly reset, some jambs appear

original. The rounded front of the turret supports loops at 3

levels in its under 4' thick wall. After a slight batter, topped

with a roll moulded string course, come 2 obviously Victorian loops, a

lancet window to the south and a precision cut crossbow loop to the

east. These are topped by crude relieving arches. This

layout is repeated in the level above, but here both apertures have the

appearance of true medieval loops. This layout is repeated on the

top floor, although the window appears more rebuilt. Internally

the embrasures of the loops are far too close together for this to have

been an original medieval layout. The eastern facing crossbow

loops are unusual in being set in the junction of the turret and

curtain. Such loops would have been of limited military use

without embrasures behind them to allow a stable fighting platform,

while their being twinned with windows makes the layout most

uncomfortable and unmilitary. Grosmont castle

has ground level simple crossbow loops like this, but those at Brecon

are powerful loops, with central sighting slits, but no basal oilets at

base or summit. The fact that the Victorians have copied this

style in their 2 replacement loops would suggest that the style is

original, as too would their crude representation in some of the

eighteenth century sketches of the site. As these loops exist to

the east, it is unusual that they do not to the south where the west

wall of the polygonal latrine turret was later added. However, as

this section of the wall has been smashed through to allow access to

the polygonal latrine turret, it is possible that they once existed,

although it seems far more likely that the surviving eastern crossbow

loops are later aesthetic additions, perhaps being added when the

corner loops were replaced with windows. Certainly E. Sparrow's

1786 sketch shows just one large Romanesque lower window with two

crossbow loops above where the lancets are now and no loops at all in

the junction which is shown as largely collapsed. This seems the

most likely reconstruction, that the 3 junction crossbow loops are

Victorian additions with the upper 2 being made of the pieces taken

from the neighbouring loops when the 2 lancets replaced them.The polygonal latrine tower has been added to the south face of the round turret roughly centrally with an appallingly built junction. The latrine tower is of 3 storeys over a basement with a latrine pit that empties eastwards into the River Honddu. In places its walls are under 4' thick. In short it was built in a post military age and is therefore possibly more fifteenth century rather than fourteenth. Close to the south wall of the hall on its west side is a shoulder headed doorway that allows external access. This is covered to the south by a single crossbow loop with fish tailed oilets to top and bottom. The northern side of this has clearly been replaced. The floor above is marked by a projecting string course which is pierced to the west by a rectangular window which appears original. The upper floor has 2 fine loops similar to the first floor one, while the Victorian battlements are set over a projecting Victorian string course. Facing east are 2 replacement loops, of which the more central one appears to have an older provenance. On the second floor is another rectangular window which cuts through the projecting string course. Again 2 loops similar to the compatriots in the west side grace the upper floor.

Inside the latrine tower, entered via the external steps to the shoulder headed doorway to the west, is a small sub-rectangular room which appears to have a relatively modern concrete floor. Beneath the southern half of this is the basement latrine pit, now only entered by the external flue to the east. As far as inspection of the now very unstable building in 1996 could ascertain, there is no trace of any garderobes on this floor or apparently in those above. Neither are there any other readily apparent garderobe flues, although there are fireplaces on the two upper floors in the north-west corner. The state of the interior totally precluded reaching the third floor, but from what could be seen from lower levels no latrines could be postulated. From the first floor chamber entrance is gained, via three modern concrete steps, into the corner turret.

It is thought that Brecon castle had a main gate to the west. This has been claimed to have been reinforced by two D shaped towers, a portcullis and a drawbridge, but of these there are no remains. Buck's print shows the remnants of what may be one or more gatetowers standing just south of the private Ely Tower house, where the castle square road now runs. Between this and the SW corner of the Castle Hotel were further fragmentary ruins of which no trace now remains. In medieval documents there are references to other rooms and buildings, viz. chambers for the constable and tax collectors, a chapel, treasury, kitchen and stables. There was also a well described as 30' deep.

Extracted from the Castles of Breconshire (Logaston Press, ISBN 1-873827-80-6) [1998], which includes Brecon Castle, Aberyscir Castle, Alexanderstone Castle, Castle Madog, Cilwhybert Castle, Clawdd British, Cwm Camlais Castle, Llanddew Castle, Llandefaelog-Fach Castle, Llanigon Castle, Llanthomas Castle, Pencelli Castle, Pont Estyll Castle, Sennybridge Castle, Trecastle, Ty'n-y-Caeau Castle, Vaynor Castle, Ystradfellte Castle, Castell Coch, Bronllys Castle, Aberllynfi Castle, Blaenllyfni Castle, Crickhowell Castle, Garn y Castell, Hen Castell, Maescelyn Castle, Scethrog Tower, Talgarth Tower, Tredustan Castle, Trefecca Castle, Tretower Castle, Twmpan Castle, Builth Wells Castle, Caer Beris Castle, Caerau Castle, Treflis Castle, Llanafan-fawr Castle, Llysdinam Castle, Forest Twdin, Castell Dinas, Crickardarn Castle, Waun Gunllwch and Llyswen.

Now out of stock. A new Kindle version should be out on Amazon by the end of 2020.