Aber

It is perilous to precisely date any medieval structure, with or

without archaeological or documentary evidence. This is

because it is difficult to be sure what structures documents refer to

and even what exactly archaeological evidence actually

signifies. This is as true for castles as for

llysoedd. In each case it is still a matter of weighing

possibilities and deciding likelihoods. However, this does

not mean that such dating should not be attempted, merely that it

should not be set in stone, especially while much of the evidence is

yet to be evaluated.

It is perilous to precisely date any medieval structure, with or

without archaeological or documentary evidence. This is

because it is difficult to be sure what structures documents refer to

and even what exactly archaeological evidence actually

signifies. This is as true for castles as for

llysoedd. In each case it is still a matter of weighing

possibilities and deciding likelihoods. However, this does

not mean that such dating should not be attempted, merely that it

should not be set in stone, especially while much of the evidence is

yet to be evaluated.

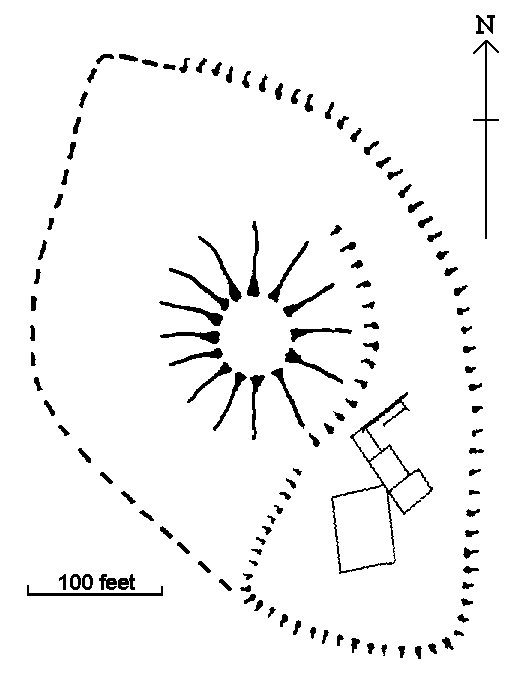

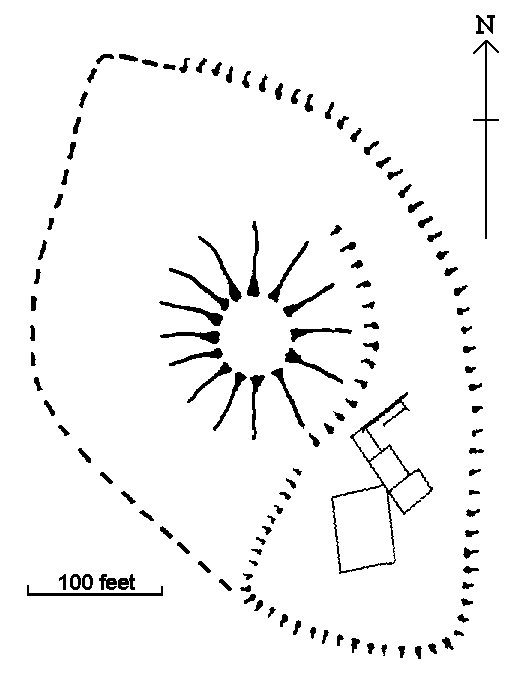

At Aber we have a still partially

ditched motte roughly 120' in diameter and a little over twenty

feet high. Such mottes literally abound throughout the

British Isles. The summit is approximately fifty feet in

diameter and shows clear signs of once having supported either a small

shell keep or large, probably round, tower. The motte was

almost certainly surrounded by a ditch as was common

practice. This is most noticeable to the south, although the

drop in height to the houses on the site of the bailey now marks its

position elsewhere. The motte appears to have been surrounded

by an eye-shaped bailey approximately 550' north to south by 350' east to west at its maximum extent. This bailey

itself would appear to have been divided roughly in half. The

dividing ditch survives mostly to the south, while to the north it may

be discernable in the aerial photograph. Most of the

bailey defences to the north and west have been obliterated by later

houses, but the distinct drop in height strongly suggests the line of

the northern bailey. The bailey defences to the south and

east have also been largely erased, possibly by ploughing, but more

likely by the deliberate destruction of the rampart which was probably

used to fill the ditch. Such degradation of the military earthworks of the site

should make us very careful of the modern suggestion that this was the

site of the hall complex of the later princes of Wales.

Within the northern bailey excavation

has uncovered a structure which has been ‘identified as the

llys or princely court recorded here through the thirteenth

century'. There are many problems with this identification

and it would appear - certainly no evidence has been advanced that any

proper historical research has been undertaken and certainly none

worthy of the name has been published - that this assertion has been

made without adequate historical research or taking llys and castle

sites in context.

The building alleged to be a royal llys

was uncovered twice, once in 1993 and once in 2010. This

structure was initially claimed to be approximately 37' east to

west by 26' north to south internally, with walls some

2½' thick. Projecting chambers, each about 20' by 30', have been claimed by the excavators as

additions built on both sides of ‘the hall'. It is

therefore necessary to examine the remains to see if they justify such

an interpretation.

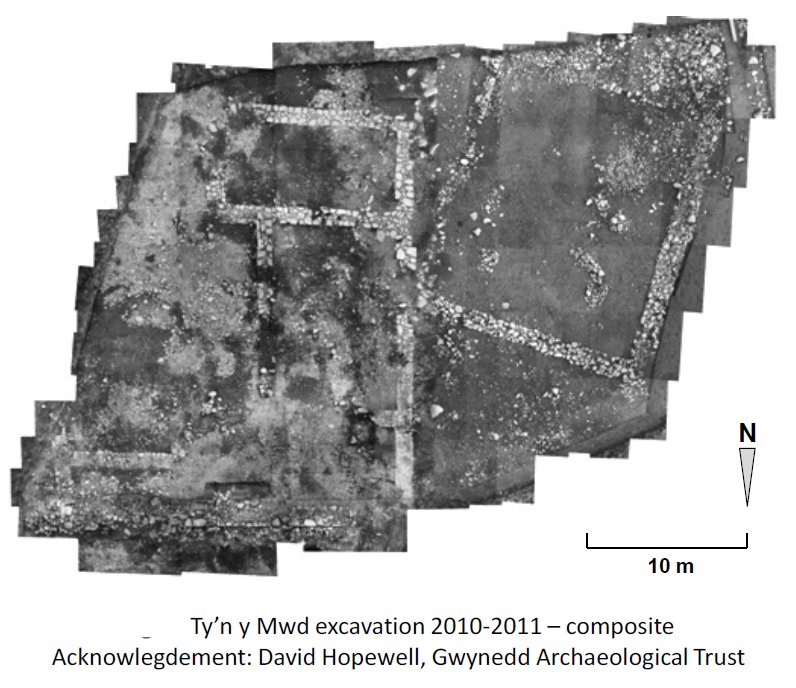

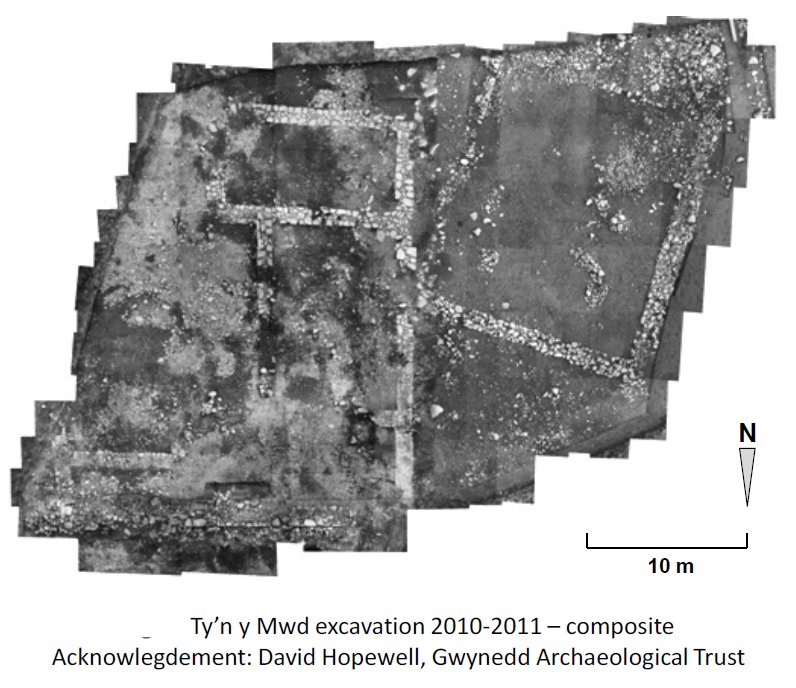

The aerial photographs of the dig site -

and a short personal inspection - would suggest the site has a complex

history which archaeology shows continued into the nineteenth century.

From the excavation reports we can judge that we are not yet anywhere

near to fully understanding the ‘modern' history of the

castle site after the Middle Ages.

The aerial photographs of the dig site -

and a short personal inspection - would suggest the site has a complex

history which archaeology shows continued into the nineteenth century.

From the excavation reports we can judge that we are not yet anywhere

near to fully understanding the ‘modern' history of the

castle site after the Middle Ages.

Firstly, a few things have to be said of

the reports that have appeared and which can be summed up in the last

government published report. These contain many claims, but

no historical research, while the few solid facts that they do contain

are used in juxtaposition with dubious identifications to

‘prove' their cause. Such a report even resorts to

‘straw man' arguments, viz: ‘Some believe that...

Pen y Bryn... [was the llys] quoting evidence from place names,

antiquarian writers, local tradition and interpretation...'.

Such misrepresentation of the facts from original thirteenth and

fourteenth century documentation does no real favours to history and is

an abomination from a government sponsored body. However,

using this final ‘preliminary report' as a basis for what has

been uncovered in the castle bailey, it is possible to make the

following observations. The south-western corner of a later

‘masonry building' has clearly penetrated the wall of the

claimed long house of the Welsh princes. For some

reason the excavators make this penetration out to be an original

doorway of their hall of the princes. If this was a doorway -

of which there seems no evidence - then why was a later building

apparently ‘of the fourteenth century' built into

it? What was this later ‘building' that shows

evidence of metal working going on within it? Was it a

building or a simple corral wall around an industrial complex

approximately 60' by 50', built after the demolition of the alleged

hall. Further, why is there no historical evidence of this

change of use of the site of a royal palace into an industrial complex

as has been uncovered by excavation, unless of course this is not the

site referred to in any of the documentation? Remember that

the capital messuage, or caput of Aber estate, as Garth Celyn was, is

mentioned as a functioning estate down to 1417 and is still being

granted by the Crown as such as late as 1485 and Pen y Bryn is

mentioned as the capital messuage of the estate of the Thomas family

during the sixteenth century.

Of the claimed ‘hall' itself,

understanding its NE section is even more problematic due to

the denuded nature of the remains, which are even worse at this

corner. The northern section of the primary building has been

almost totally obliterated with the NE corner totally

lost. The junction of the NW corner with the claimed

‘north wing' is not clear, but the better quality mortar in

the ‘wing' wall would suggest that it abuts onto the primary

chamber wall. The rest of the so called ‘north

wing' appears to be illusory, but more will be said of this later.

Two entrances have been claimed into the

‘hall house'. The first, to the east, is less than 3' wide and consists of a simple break in the wall without a

doorstep. As this is overshadowed by the claimed

‘wing' to the south and a later wall which abuts to the

north, it probably was an entrance of a very poor kind. It

would also appear to have been covered by an outbuilding or porch

judging by the remains. This is hardly the great porchless

ceremonial entrance which appears on the imaginative reconstruction of

the surprisingly misnamed ‘Ty'n y Mwd' hall. The

second ‘entrance' to the west, which we have already examined

above, is even more imaginative. This is simply a gash carved

through the wall where the later, apparently industrial complex was cut

through what therefore appears to be an abandoned primary

building. If the building was occupied and of a high status

it would not have been pierced by such a lowly structure.

The building claimed as the southern

‘wing' of the ‘hall' is 35' by 16'

internally. The foundations of this chamber are mostly

intact, although much of the east wall has gone. It appears

to all be of one build except for a later external buttress added

roughly half way down the southern wall. That the eastern

wall of the ‘hall' penetrates the northern wall would suggest

that it post dates this structure. However, it could just be

a change in building plan that happened virtually contemporaneously

with the building of the ‘hall'. A

‘bronze ring brooch... of thirteenth to fourteenth century

date' was recovered ‘from the interface of the old ground

surface within the south wing of the building'. This would

‘suggest' that the brooch was lost after the building was

abandoned and before much soil built up. It is hardly

satisfactory dating material and if anything points to a pre fourteenth

century date for the abandonment of this structure. If this

assumption is correct, it shows that this could not have been the

palace of the princes as this was still in occupation in the

fifteenth century.

The northern part of the excavation site

shows at least four or five phases and has obviously had a more complex

history than the two structures to the south, identified by Gwynedd

Archaeological Trust (GAT) as a hall and its later wing. This

northern section is also the best preserved part of the masonry and the

thickest, with the wall approaching 6' thick. In front

of the northernmost wall was a ditch which was not fully explored by

the excavators. This is a shame as it would appear to have

been the ditch dividing the northern bailey from the southern one,

which would make the northern wall of the excavated complex the curtain

wall of the southern bailey of the castle. This purported

curtain wall would appear to have been rebuilt with a new, narrower

wall topping the remains of the earlier one, of which only the northern

front can now be seen.

The northern part of the excavation site

shows at least four or five phases and has obviously had a more complex

history than the two structures to the south, identified by Gwynedd

Archaeological Trust (GAT) as a hall and its later wing. This

northern section is also the best preserved part of the masonry and the

thickest, with the wall approaching 6' thick. In front

of the northernmost wall was a ditch which was not fully explored by

the excavators. This is a shame as it would appear to have

been the ditch dividing the northern bailey from the southern one,

which would make the northern wall of the excavated complex the curtain

wall of the southern bailey of the castle. This purported

curtain wall would appear to have been rebuilt with a new, narrower

wall topping the remains of the earlier one, of which only the northern

front can now be seen.

The northern ‘wing' of the

alleged palace seems more to have been drawn with the eye of faith

rather than from evidence on the ground and if there is an eastern

return wall it would appear to be west of the eastern wall of the

primary chamber. In other words this is hardly a

wing. Further east from the northern ‘wing' are the

remains of what appears to be a long narrow building which partially

underlies the secondary ‘curtain wall'. This

structure, and the claimed north ‘wing' were all said to have

been built with lime mortar. The rest of the masonry

uncovered was said to be clay or earth mortared walls.

To the west of the southern half of the

main excavated structures just described is a large rectangular

enclosure that has already been mentioned as its foundations have

pierced and obliterated a portion of the west wall of the

‘hall'. This structure has slightly thicker walls,

that are not as well constructed as the walls of the south

‘wing'. It is approximately 55' east to west by 60' north to south externally. Excavation shows that

it contained at least six pits as well as burnt soil. As such

it would appear to have been an industrial site which postdates the

‘hall' to the east which has been claimed by GAT as

Llywelyn's llys.

The official government agency summary

of the site is twofold and date from 2007. Under the heading: The Llys at Aber, House Excavated at Pen y Mwd comes:

The llys or princely court at Aber was one of the principal residences

of the princes of Gwynedd through the thirteenth century. Repairs are

recorded in 1289 and 1303, following the English conquest. Remains were

still visible in the early sixteenth century. Excavations in 1993 recovered the plan of a hall with crosswings at

either end, associated with thirteenth and fourteenth century material.

The hall was 11.2m by 8.0m internally. The site lies close by the foot of a castle mound (NPRN 95692). There

are several other instances in north Wales of apparently unfortified

houses associated with castle mounts, for example Castell Prysor (NPRN

308964), Crogen (NPRN 306558) and Rug (NPRN 306598). In these cases the

mount can be regarded as an adjunct to the house, conferring a certain

status and arguably furnishing a refuge.

A second entry has: Aber Castle; Pen-y-Mwd Mound:

A mound thought to be a

medieval castle mount associated with a medieval mansion excavated at

its foot (NPRN 309171). This is a sub-circular steep sided mound,

roughly 36m in diameter and 6.6m high. It has a level summit

about 17m by 14m. There are traces of a ditch on the south side,

but no further defensive features have been identified. The

mansion was excavated in the field to the south-east. It produced

thirteenth and fourteenth century material and is identified as the

llys or princely court recorded here through the thirteenth

century. There are several instances in north Wales of castle

mounts associated with apparently unfortified houses, for example

Castle Prysor (NPRN 308964), Crogen (NPRN 306558) and Rug (NPRN

306598). It is possible that the mount was raised as an adjunct

to the court.

In the official mind there is no doubt that the buildings uncovered by

excavation in the castle bailey are those of the llys of the princes of

Gwynedd, which is rather unfortunate as this case is devoid of clear

documentary evidence. Indeed what original evidence there is

(medieval royal documents from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century) tends far

more to point towards the extensive site at Pen y Bryn

on the Garth (roughly 250' square), rather than to the site in

one of the baileys of Aber castle (a roughly triangular shape

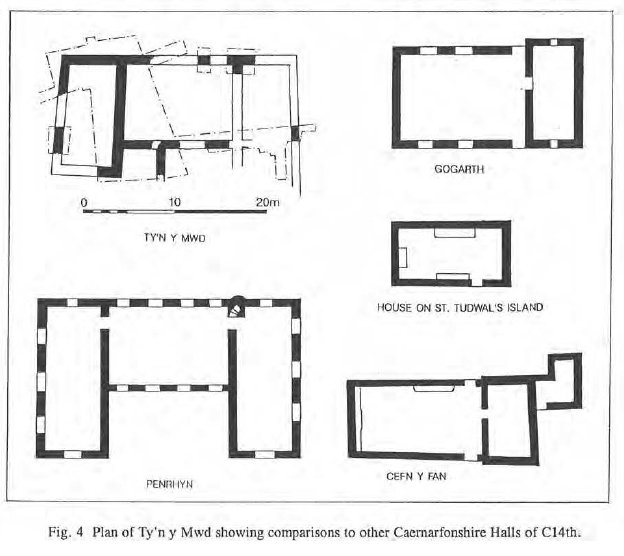

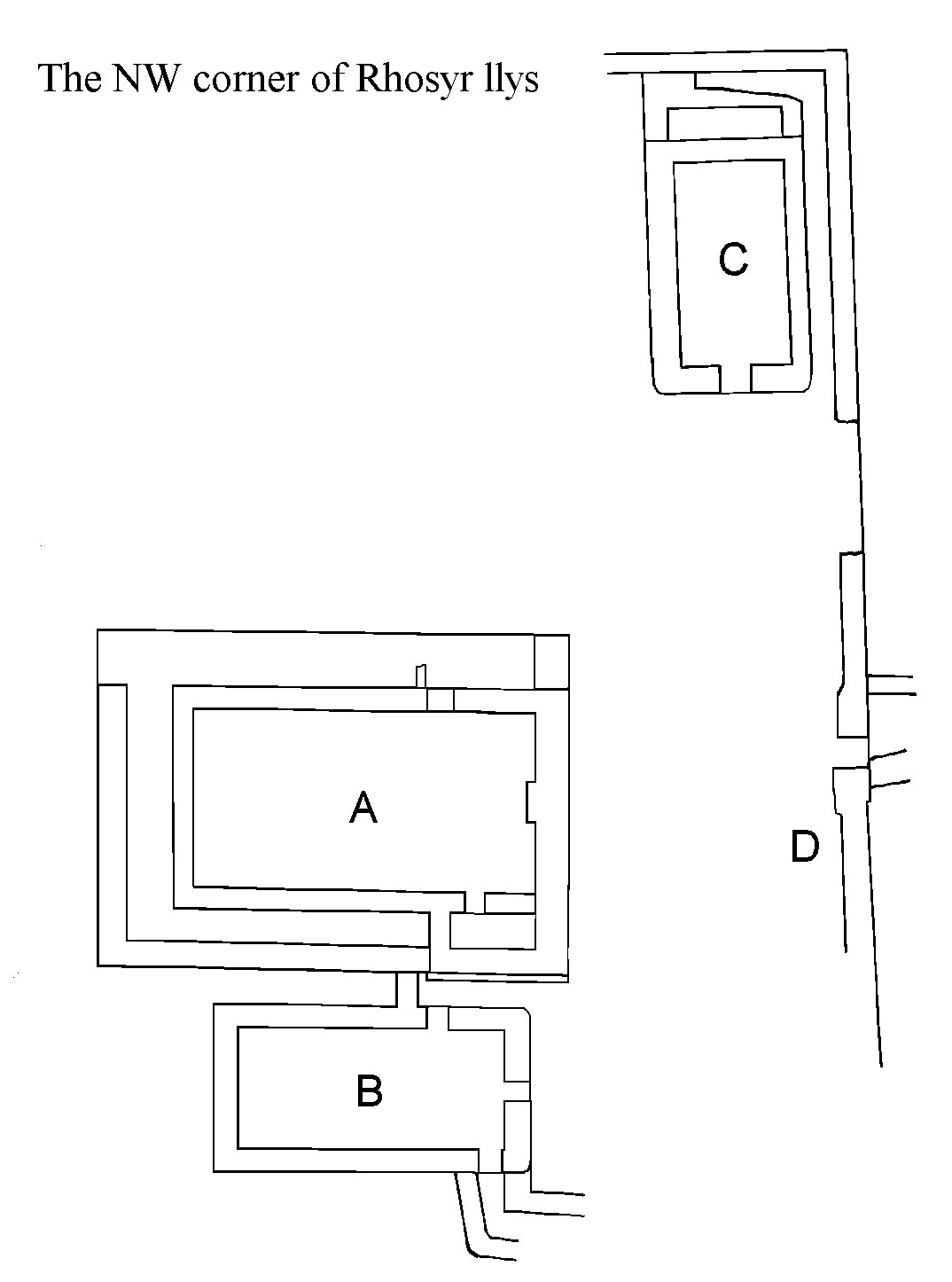

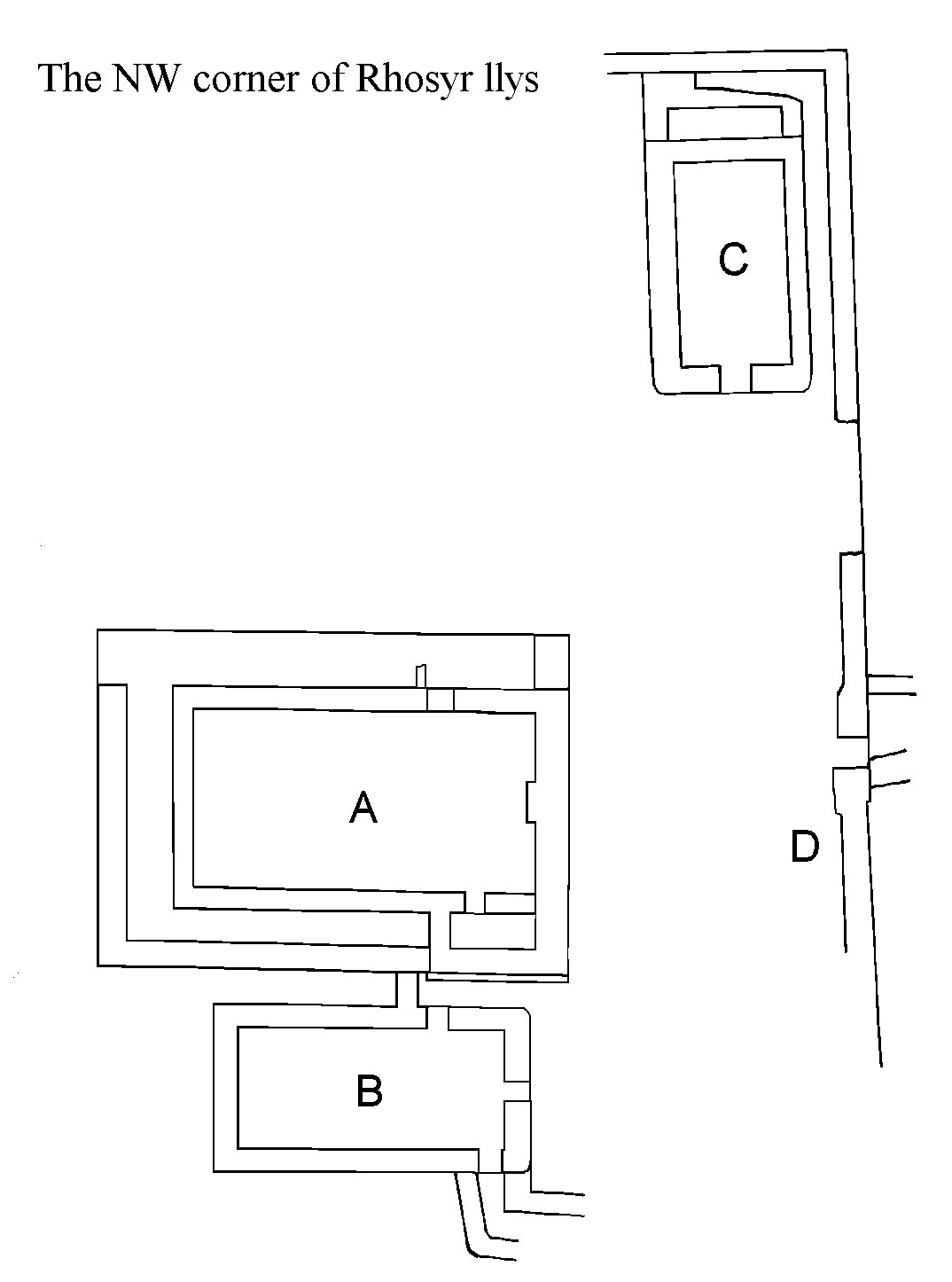

roughly 150' by 120'). Most llys sites, Llys Gwenllian, Rhosyr

and the tentative site at Aberffraw, all seem to be rectangular and in

the region of between 200' and 250' long.

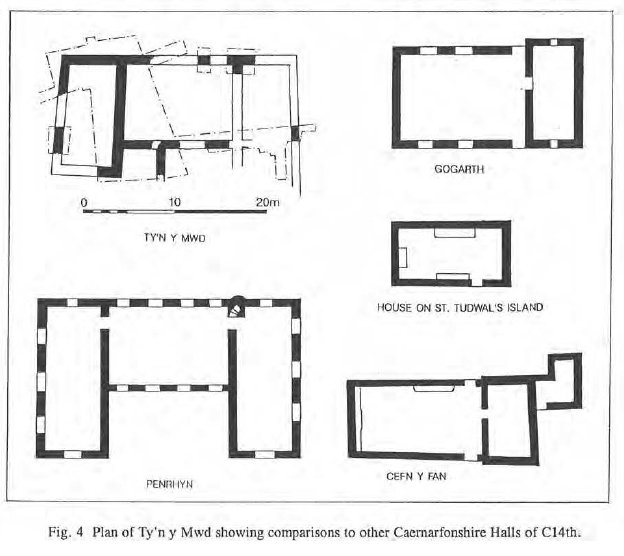

What we certainly have in the southern castle bailey at Aber are the remains of

what is a series of structures quite unlike those excavated at Rhosyr

llys and apparently unlike any of the remains found at other houses of

the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Indeed the only

‘Caernarfonshire halls of the fourteenth century' which

looked even remotely like the Aber bailey site was a debatable

reconstruction plan of Penrhyn (above right). The current walls all lie

within the southern bailey of Aber castle, stand no more than a course

or two high, and show no sign of mortar other than poor leached remains

seen to the north. What is left bears no resemblance to a

‘high status building'. It appears more like the

jumble of buildings that would be expected in a castle bailey. It should also be noted that these remains are

inferior to the possibly thirteenth to eighteenth century hafod

buildings uncovered by excavation in 1961. It is further

quite clear that the poor quality of the remains is not solely due to

stone robbing. These structures were never of any great

standing and probably were only one storey high, judging by the

thinness of the walls and the paucity of the ‘mortar'.

Apparently the pottery remains at Aber

would suggest a thirteenth to fourteenth century usage for the

buildings. Yet again the amount of pottery and coins found on

such a small site is extraordinary, especially as royal sites were

always well maintained and kept scrupulously clean. For

example, the fourteenth century details for the cleaning of the royal

castle of Berkhamsted have survived and it would seem unlikely that

other royal sites would have been allowed to become so unkempt as the

alleged palace in the bailey of Aber castle is said to have

been. Thus we find in 1351 the porter of Berkhamsted castle

was allowed all the litter found within the castle buildings whenever

they were cleaned, which appeared to be a yearly business.

Although masses of such minutia have not survived from most

habitations, the cleanliness of royal sites when excavated shows that

such agreements were widespread. Indeed, even the baronial

castle of Hen Domen at Montgomery was kept so clean during its two

hundred odd years of occupation that the excavators were appalled by

the lack of dateable evidence found. This therefore adds to

the impression that Aber castle was not the royal house used by Edward

I and II and their Welsh predecessors.

It is a shame that excavation did not

take place on the motte which would have shown if the masonry of the

keep was similar to that uncovered in the bailey. If it had

been we may have been able to tell if the whole structure had been

revamped after its destruction in 1094 when all the castles of Gwynedd

were certainly destroyed. This might have told us a great

deal about the site and the dates of its occupation. A small

dig upon the motte may well still show us the life span of the motte

and bailey castle.

It is a shame that excavation did not

take place on the motte which would have shown if the masonry of the

keep was similar to that uncovered in the bailey. If it had

been we may have been able to tell if the whole structure had been

revamped after its destruction in 1094 when all the castles of Gwynedd

were certainly destroyed. This might have told us a great

deal about the site and the dates of its occupation. A small

dig upon the motte may well still show us the life span of the motte

and bailey castle.

It has been asserted that the

foundations uncovered in Aber castle bailey can be related to the

rebuildings carried out for Prince Edward in the early fourteenth

century and that antiquarians often state that this was the site of the

llys. Neither of these arguments stand up to serious

consideration. The best preserved part of the structure is to

the north where one ‘wall' has been overlain by several large

river-worn boulders. The whole could be little more than

sleeper walls for a wooden structure. Certainly to describe

the foundations as they appear as a mansion or royal hall seems rather

grand and the reconstruction drawing of ‘the castle' as it

was said to have been in the early fourteenth century is positively

misleading, especially when compared to the one drawn for

Rhosyr. In the reconstruction at Aber the petty east entrance

into the primary building has lost its porch, while the low foundations

which have the appearance of sleeper walls have been imagined into a

two storey structure which positively dwarfs the motte and ignores the

industrial compound to the rear as well as the wall and ditch between

it and the motte.

It is worth noting that Aber castle

motte and bailey stands immediately west of the fast running Afon Aber,

just at the place where the river valley widens out into the coastal

plain. It therefore controls the river crossing and is in a

lowland position. It should again be emphasised that it is a

well recognised general principal that Welsh castles tend to dominate

the highlands and Norman castles the lowlands, although both sides on

occasions used the others' fortresses. It can therefore be

seen that the remains uncovered by excavation at this site are in

accordance with what has been found and is expected at other Norman

sites, but they do not meet with the criteria found at other llys

sites, viz Rhosyr.

Copyright©2016

Paul Martin Remfry

It is perilous to precisely date any medieval structure, with or

without archaeological or documentary evidence. This is

because it is difficult to be sure what structures documents refer to

and even what exactly archaeological evidence actually

signifies. This is as true for castles as for

llysoedd. In each case it is still a matter of weighing

possibilities and deciding likelihoods. However, this does

not mean that such dating should not be attempted, merely that it

should not be set in stone, especially while much of the evidence is

yet to be evaluated.

It is perilous to precisely date any medieval structure, with or

without archaeological or documentary evidence. This is

because it is difficult to be sure what structures documents refer to

and even what exactly archaeological evidence actually

signifies. This is as true for castles as for

llysoedd. In each case it is still a matter of weighing

possibilities and deciding likelihoods. However, this does

not mean that such dating should not be attempted, merely that it

should not be set in stone, especially while much of the evidence is

yet to be evaluated.

The aerial photographs of the dig site -

and a short personal inspection - would suggest the site has a complex

history which archaeology shows continued into the nineteenth century.

From the excavation reports we can judge that we are not yet anywhere

near to fully understanding the ‘modern' history of the

castle site after the Middle Ages.

The aerial photographs of the dig site -

and a short personal inspection - would suggest the site has a complex

history which archaeology shows continued into the nineteenth century.

From the excavation reports we can judge that we are not yet anywhere

near to fully understanding the ‘modern' history of the

castle site after the Middle Ages. The northern part of the excavation site

shows at least four or five phases and has obviously had a more complex

history than the two structures to the south, identified by Gwynedd

Archaeological Trust (GAT) as a hall and its later wing. This

northern section is also the best preserved part of the masonry and the

thickest, with the wall approaching 6' thick. In front

of the northernmost wall was a ditch which was not fully explored by

the excavators. This is a shame as it would appear to have

been the ditch dividing the northern bailey from the southern one,

which would make the northern wall of the excavated complex the curtain

wall of the southern bailey of the castle. This purported

curtain wall would appear to have been rebuilt with a new, narrower

wall topping the remains of the earlier one, of which only the northern

front can now be seen.

The northern part of the excavation site

shows at least four or five phases and has obviously had a more complex

history than the two structures to the south, identified by Gwynedd

Archaeological Trust (GAT) as a hall and its later wing. This

northern section is also the best preserved part of the masonry and the

thickest, with the wall approaching 6' thick. In front

of the northernmost wall was a ditch which was not fully explored by

the excavators. This is a shame as it would appear to have

been the ditch dividing the northern bailey from the southern one,

which would make the northern wall of the excavated complex the curtain

wall of the southern bailey of the castle. This purported

curtain wall would appear to have been rebuilt with a new, narrower

wall topping the remains of the earlier one, of which only the northern

front can now be seen. It is a shame that excavation did not

take place on the motte which would have shown if the masonry of the

keep was similar to that uncovered in the bailey. If it had

been we may have been able to tell if the whole structure had been

revamped after its destruction in 1094 when all the castles of Gwynedd

were certainly destroyed. This might have told us a great

deal about the site and the dates of its occupation. A small

dig upon the motte may well still show us the life span of the motte

and bailey castle.

It is a shame that excavation did not

take place on the motte which would have shown if the masonry of the

keep was similar to that uncovered in the bailey. If it had

been we may have been able to tell if the whole structure had been

revamped after its destruction in 1094 when all the castles of Gwynedd

were certainly destroyed. This might have told us a great

deal about the site and the dates of its occupation. A small

dig upon the motte may well still show us the life span of the motte

and bailey castle.