Rometta

Rometta was certainly a powerful Byzantine castle. The

fortress is thought to have stood on the site of an earlier Greek

work. It fell to the Arabs under Ibn Ammar after a year long

siege in 965, nearly 90 years after the fall of Syracuse in 878 and an unsuccessful attack in 884.

In 1038 the Byzantines returned under George Maniakes and, after taking

Messina, they moved onto Rometta, which soon

fell to their assault after some heavy fighting. All was lost in

1040 when Maniakes was disgraced in a political coup and the Arabs

retook all his gains. The castle is next mentioned when Count Roger Hauteville (d.1101), after an unsuccessful recce to the district in 1060, occupied Milazzo

and Rometta with an army of 160 knights and 700 infantry in February

1061 on his first invasion of Sicily. After Roger's defeat at Messina,

both fortresses were abandoned. When in May 1061 Roger returned

with his brother, Robert Guisard (d.1085), they advanced on Rometta

with their ally, Ibn al-Hawas, and the castle was tamely surrendered to

them by Ibn at-Timnah's castellan who swore loyalty to Robert on the

Koran. Robert then handed the keys to the city of his brother, Count Roger. From here they marched on Enna.

In 1081 Rometta was recorded as a part of the diocese of Troina.

The Arab geographer Edrisi, in his 1154 work, The Book of Roger,

records the town as a fortress (qal'a). In April 1168 the Messina

rebels ‘occupied Rometta, a strong fortress, after easily

overcoming the castellan's loyalty with promises'. That same year

the rebellion swept westwards into Palermo bringing Chancellor Stephen Perche's regime to an end.

During the Swabian period Rometta castle, listed among the castra exempta of Frederick II (d.1250),

was state-owned. The castle remained in the hands of the Crown,

although it was garrisoned by Peter Ruffo of Messina (d.1256+) after

the death of Frederick II in 1250. After his defeat at Piazza

Armerina in November 1254 it was surrendered by him to the

Messinans. On 3 May 1272 its Angevin garrison was

supposed to consist of merely a single knight. In 1294 King James II (d.1321) granted the castle to Bernard Ferro on condition that he repaired it. Shortly before 1337 Frederick III

(d.1337) made the castle his home. The castle remained in use and

in 1543 the military engineer Antonio Ferramolino proposed

strengthening the defences by making the city walls strong enough for

artillery and demolishing the houses both on the defences and within

40' of them. This does not appear to have been done although the

castle remained an important military stronghold in the sixteenth

century. During the Spanish reconquest of the island in

1718-1719, the castle was used as a base and as late as 1757 Abbot Vito

Amico called Rometta ‘a very expansive fortress'. It

may still have housed artillery this late.

Description

Rometta lies in the mountains some 3 miles south of the coast and

occupies a flat crag dominating the surrounding lower lands. The

entire hilltop would seem to have been the Byzantine castle, which

would have made it more a defensible city than a castle as thought of

today. That said, the castle which is the heart of the defences

at the top of the hill would also appear to be Byzantine in origin and

fits nicely into the battleship style Byzantine fortress as described

under Aci castle.

The city defences on the hilltop somewhat resemble a 4 legged star

fish. The main gates are to the northeast and southeast, while steep scarps and

crags defend the rest of the hill which was apparently also

walled. To the southeast is the Porta Milazzo or town gate. This

is still the main and difficult entrance to the town. Near this

is the square Byzantine church of Maria e Gesu o Badavecchia with its

octagonal central tower and Romanesque windows. The gate itself

has been much rebuilt and enlarged to allow motor access. The

walls on either side of it have been much built into, but still show

the strength of the site.

At the northeast end of the town site is a ridge on the end of which is the

Porta Messina. This allows access to a ramp than runs down the

crag to the southwest before doglegging to the northeast. The wall is still

battlemented and the gate is offset in a polygonal projection.

The outer arch to the north is pointed, while the inner arch is

Romanesque. The surrounding walls are rubble built and contain

much Roman brick, some of it laid in levelling layers. The

curtain running back to the southwest follows the cliff top and is still

battlemented. It also contains a battery of small ground floor

loops which appear to have had a wooden walkway on top, making up the

battlement's wallwalk.

Roughly centrally in the defended plateau is the elongated

‘battleship' site of the castle proper. This is now

misleadingly called the castle of Frederick II,

but there can be little doubt that the castle long predates Frederick's

reign (1197-1250). The site is some 600' long and no more than

60' wide. As such it appears a typical Byzantine plan, designed

to keep manpower usage to a minimum. The castle seems to have

consisted of 3 parts. To the northwest was a tower block, while

to the southeast were 2 (or more) conjoined towers now known as the

palace.

Between them lay the long body of the castle, the centre of which is

now occupied by a waterworks. There is also a central entrance to

the southwest and possibly also opposite this to the northeast.

The curtain

wall at this point, where it survives best to the southwest, is almost

6' wide

and standing some 10' tall. The masonry here lacks Roman tiles in

its rubble makeup. It is therefore possibly Norman and certainly

later than the 2 complexes at either end of the site.

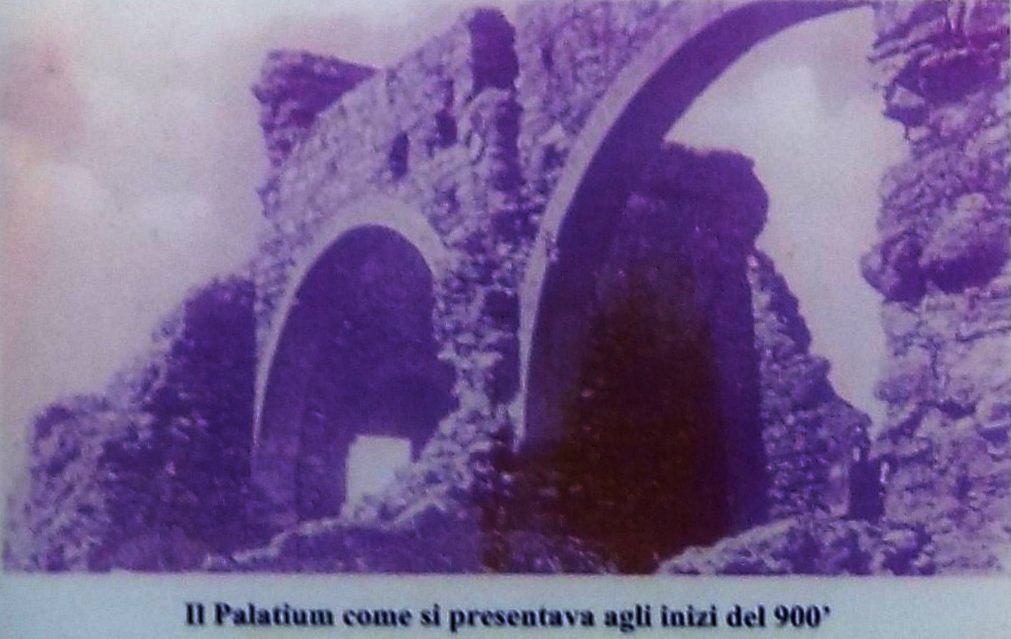

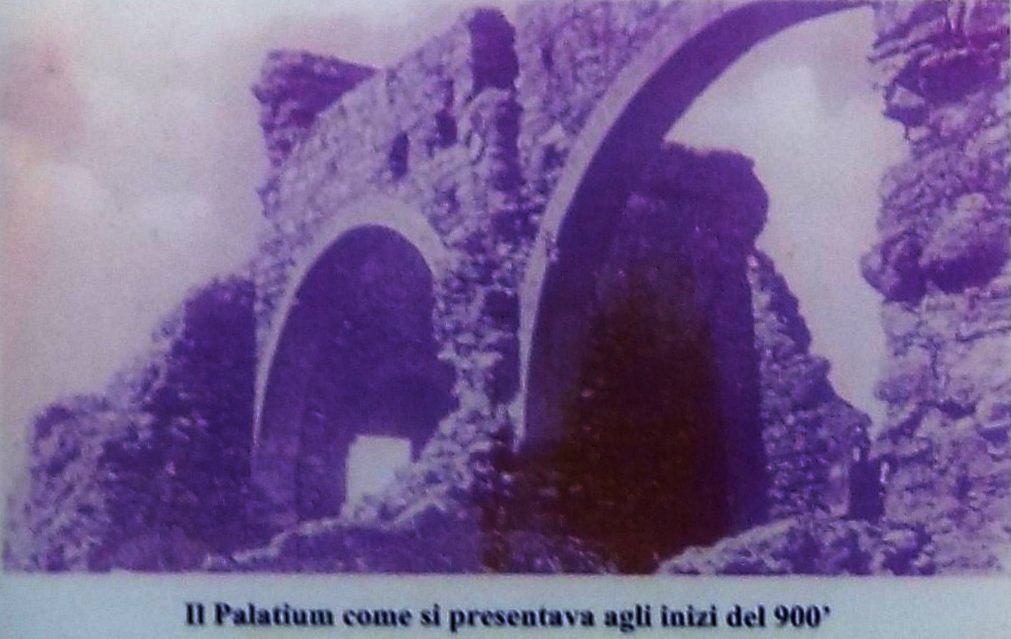

The palace, sometimes referred to as the keep, seems to be the main

residential block of the fortress. Its larger, or northeast tower, is

about 50' by 40' and divided into 2 equal halves by a crosswall.

The smaller southwest tower is about 40' by 30' and both have walls about 5'

thick. With both structures the building technique is the same,

rough slabs of limestone encapsulated by well laid layers of Roman

tile. The corners are further strengthened by well laid ashlar

around the quoins. It would seem possible that the castle walls

linking this tower to the north were added later, at least at their

higher levels, for the curtain partially overlies a first floor

Romanesque window to the northwest. Entrance to the tower was also

gained on this side via a central first floor doorway of typical

architrave Byzantine style. Similar style doorways still survive at Aci, Adrano, Belvedere of

Fiumendinisi, Caccamo, Calatabiano and Montalbano Elicona in Sicily. Such doorways can be seen as far north as Llangeais castle along the Loire in

France and as far west as Carcassonne castle near Spain.

On the northeast side of the northwest tower at Rometta, the plastering is similar to

that found in the tower of the Messina gate, leaving the lines of Roman

tiles protruding through the plaster. The southwest tower has a fine 40

degree sloping plinth at its base and is set both on bedrock and on a

wide plateau at the end of the site, rather than being right on the

edge of the drop down to town level. It also only has an entrance

to the other tower to the north at first floor level and no other

apertures. Possibly there was a further storey above.

The southwest wall of the northwest tower is mostly down from the junction with the

SE tower, but foundations remain. Internally the northwest tower was

once rib vaulted, the remains of the ribs still being partially

traceable on the north and south walls. The basement has mostly been

filled in with rubble, but the northeast corner is open nearly to its full

depth. The remaining top section of the north wall may suggest

that the tower had a flat wooden roof at this level. Certainly

there is no trace of mural stairs or a further floor.

The idea that these plainly pre-Norman features are Swabian is clearly

bizarre. Worse is the fact that one of the ribs which held up the

southeast tower's vault has collapsed in the last hundred years or so,

although luckily it was photographed before its collapse.

Why not join me at other Sicilian

castles? Information on this and other tours can be found at Scholarly

Sojourns.

Copyright©2019

Paul Martin Remfry