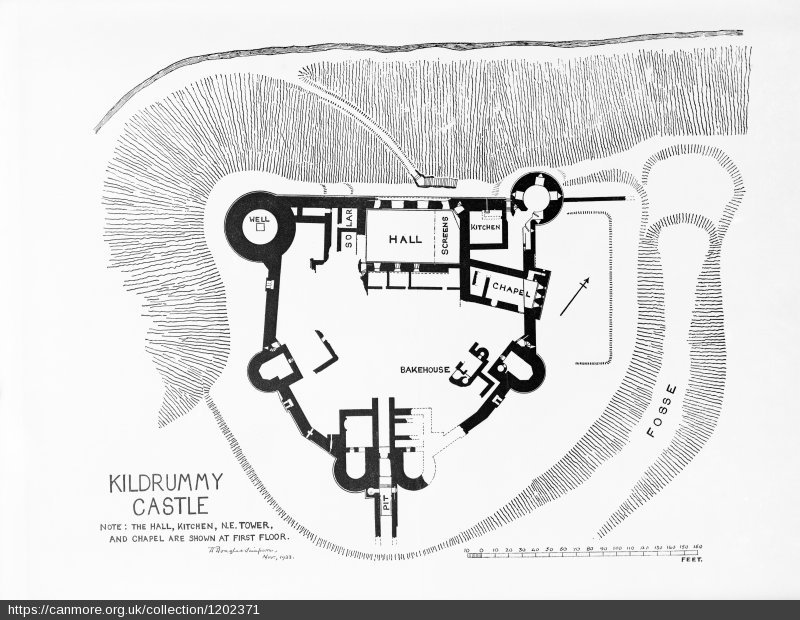

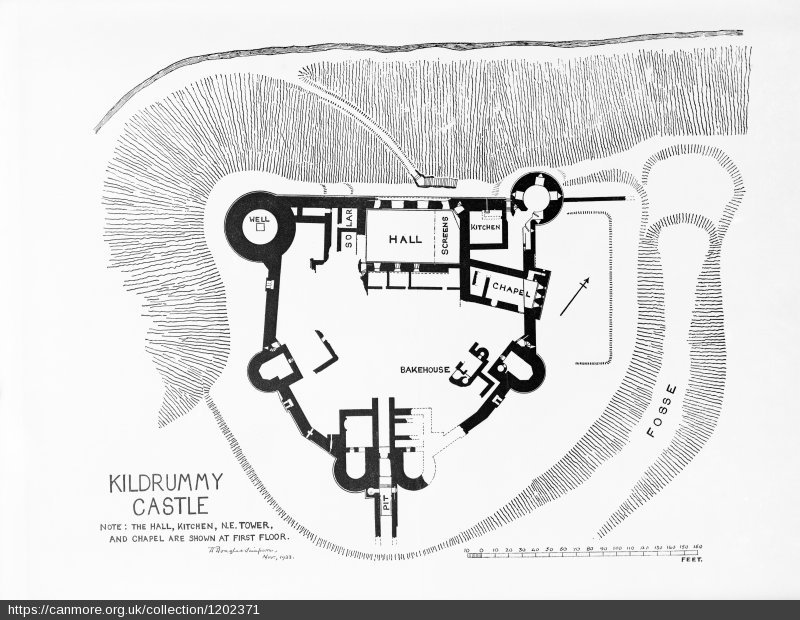

Kildrummy Castle

The much ruined Kildrummy castle was a seat of the earls of Mar from

the thirteenth century to the eighteenth. It was defended to the north by the steep

natural gorge. It was from here that much of the stone for the

castle was quarried. On the more accessible front it was

protected by a broad ditch. In plan the castle is shield shaped,

with the flat top to the north.

History

According to Wikipedia ‘the castle is likely to have been built

in the mid thirteenth century under Gilbert de Moravia'. Yet a short period

of study rapidly discovers that the only Gilbert of that name was

bishop of Caithness (1223-45) and founder of Dornoch cathedral.

There is no contemporary evidence at all to connect him with Kildrummy

castle, but there is a single claim that Gilbert was the builder of the

castle made about 1630 - or 400 years after alleged event. A

single entry of 1509, ie 350 years after the event, states that the

bishop garrisoned, built and repaired castles and other edifices for

the benefit of king and state. As we know that Earl Duncan of Mar

and his son William were lords of the district that contained Kildrummy

during the bishop's rule, it seems unlikely that Gilbert might have

founded the castle within their fiercely independent domain. Once

again Wikipedia is clearly guilty of fabrication, though it should be

noted that the doyen of Scottish castle studies, W. Douglas Simpson,

accepted this argument in 1928 and bolstered it with the fact that

Kildrummy is halfway between Brechin and Elgin cathedral.

However, one court case against many, in this case in 1449 between

claimants to the barony, specifically links Kildrummy castle with the

earldom of Mar and there is good reason to accept this fifteenth century legal

claim that Kildrummy was the capital messuage or centre of the earldom.

In reality it seems best to accept that Kildrummy

would appear to have been founded by the earls of Mar, descendants of

the mid twelfth century Earl Morggan, rather than by a French, Flemish or

English aristocratic family. There is nothing to connect the

castle with the Moravia or Moray family, who are so prominent elsewhere

in Scotland. That said, Kildrummy may well have been built

simultaneously with and in opposition to Coull castle - the fortress of

the Durward family who tried to claim all Mar in the 1220s. Both

castle designs share much in common.

Kildrummy castle is first mentioned on 31 July 1296

when King Edward I was staying at the castle of Kyndrokirn or

Kindromy. He remained there until 2 August. On 1 August the

king had presided over two trials of inmates from the gaol, which

presumably lay within the castle. One man was found guilty and

hanged for murder. The castle at this time was specifically said

in royal documents to belong to the earl of Mar. Ten days

earlier, on 21 July, Sir William Moravia, the lord of Bothwell, had,

like the rest of the Scottish baronage, renounced the French alliance

and King John Balliol and sworn homage to King Edward I at nearby

Aberdeen. The king was again at Kildrummy between 4 and 9 October

1303, while for the second time campaigning in the Highlands. It

has been suggested that the payment of £100 to Master James St

George on 14 October 1303 was in response to Edward's visit and that

this resulted - to paraphrase briefly - in the building of the castle

gatehouse because it was twin towered and therefore must have been

based upon Harlech which James is claimed to have built and it is

similar to the gatehouse at Conway which cost £125. However,

such arguments fall apart under a brief survey of the historical

evidence. Firstly Master James was not responsible for building

the gatehouse at Harlech and Conway castle has no twin towered

gatehouse. The town mill gate was built in the 1280s but cost way

over twice £125. Further there are no records of the

necessities that would have been purchased by the king if he was

working on Kildrummy castle. Then there comes the argument of why

would Edward build a gatehouse at this isolated fortress that did not

belong to him when he had his own castles nearby? Quite clearly

the argument that he is responsible for any part of the masonry at

Kildrummy, without any documentary evidence or logical reason, is

implausible. Sadly it is a well-believed fantasy.

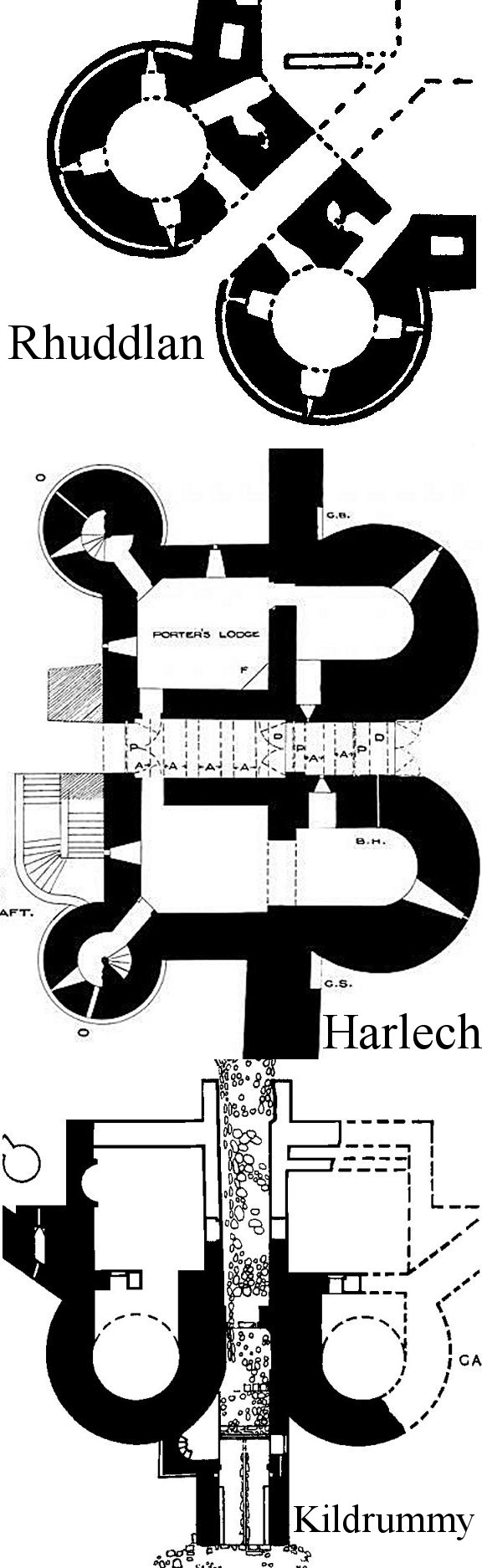

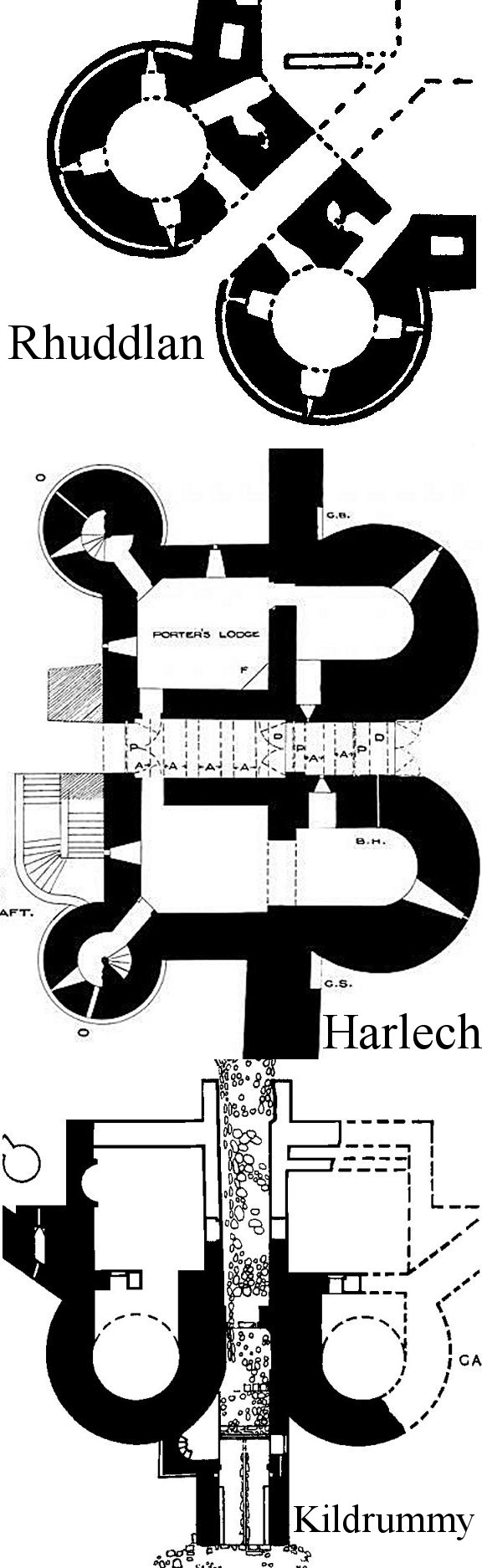

Regardless of fantasy, Kildrummy gatehouse does fit into a British

Isles wide style of twin towered gatehouse, though not the Harlech

king, which had twin spiral stairs in round turrets to the rear.

The standard, turretless gatehouse exist at various English castles, viz: Beeston, Bungay, Clifford, Dover, Longtown, Pembridge, St Briavels, the Tower of London and Whittington. In Wales they exist at Caerphilly, Carmarthen, Chepstow, Criccieth, Degannwy, Dinas Bran, Llawhaden, Neath, Oystermouth, Powis, Rhuddlan, Tinboeth and White Castle. In Scotland one can also be found at Urquhart, while finally in Ireland they survive at Carrickfergus, Castle Roche, Dungarvan, Limerick and Roscommon.

Once the family of Moray and the works of Edward I

are removed from the equation we are left with the foundation of the

castle by the earls of Mar sometime in the twelfth or thirteenth century. It

would seem possible that Earl William (1244-81) was responsible for

founding the castle. He was married to Elizabeth Comyn (d.1267),

the daughter of Earl William Comyn of Buchan (1163-1223). Comyn

had founded Deer abbey in 1219 and the style of the few fragments that

remain - Romanesque archways and small rectangular windows - bring to

mind much of the early masonry work seen in the castles of

Scotland. It therefore seems possible that Earl William was

copying the work of his father-in-law, if he were responsible for

founding Kildrummy castle. Certainly in the 1250s William found

himself under attack by his neighbour, Alan Durward of Coull and

Urquhart, who unsuccessfully claimed the earldom of Mar for

himself. Such claims would have been a great impetus in building

a modern up to date fortress at Kildrummy in place of the ancient motte

and bailey castle at Inverurie, which had previously been the earls'

caput. Interestingly William appears to have campaigned in Wales

during 1277. He may therefore have seen King Edward's castles at

Flint and Rhuddlan, which both consisted of base courts with powerful

round towers in the circumference. Rhuddlan also has 2 powerful

twin-towered gatehouses. These are nearer to the design of

Kildrummy than Harlech, though the nearest match is undoubtedly

Bothwell or Urquhart.

It was William's son, Earl Donald (1281-97), who was

lord of Kildrummy while King Edward I stayed there. Sometime after 1266,

when Earl Malcolm of Fife died, Earl William married his widow,

Helen. She appears not to have been the Susannah Ferch Llywelyn

ab Iorwerth of Wales who had given Malcolm two children, despite

Wikipedian claims to the contrary. In any case, between 1266 and

1297, Helen bore Donald 3 surviving children, one of whom, Isabella,

bore Robert Bruce, later to be king, a daughter called Marjorie.

She died in 1296, possibly while giving birth. The marriage and

perhaps personal inclination tied Donald solidly to Bruce's claim to be

king of Scotland and he was often found working in harmony with that

family. Despite this, he broke with Bruce and joined the 1295

rebellion and was amongst the barons taken at Dunbar in April

1296. This was followed, on 10 July, by William performing homage

to the king at Montrose when King John Balliol surrendered his

kingdom. On 23 June 1297, Donald promised to serve King Edward I in

France and consequently received permission to return to

Scotland. He was back in the country, but dead by 25 July.

The manner of his death is unknown. However he may have died

putting down the rebellion of Andrew Moray, as his son, Earl Gartnet of

Mar, claimed to have done by 11 June 1297 and is related above under

the castles of Urquhart and Duffus. Earl William's son,

Alexander, was still in the Tower of London as a prisoner with Edward

Balliol, the future king of Scotland, on 12 December 1297.

It was William's son, Earl Donald (1281-97), who was

lord of Kildrummy while King Edward I stayed there. Sometime after 1266,

when Earl Malcolm of Fife died, Earl William married his widow,

Helen. She appears not to have been the Susannah Ferch Llywelyn

ab Iorwerth of Wales who had given Malcolm two children, despite

Wikipedian claims to the contrary. In any case, between 1266 and

1297, Helen bore Donald 3 surviving children, one of whom, Isabella,

bore Robert Bruce, later to be king, a daughter called Marjorie.

She died in 1296, possibly while giving birth. The marriage and

perhaps personal inclination tied Donald solidly to Bruce's claim to be

king of Scotland and he was often found working in harmony with that

family. Despite this, he broke with Bruce and joined the 1295

rebellion and was amongst the barons taken at Dunbar in April

1296. This was followed, on 10 July, by William performing homage

to the king at Montrose when King John Balliol surrendered his

kingdom. On 23 June 1297, Donald promised to serve King Edward I in

France and consequently received permission to return to

Scotland. He was back in the country, but dead by 25 July.

The manner of his death is unknown. However he may have died

putting down the rebellion of Andrew Moray, as his son, Earl Gartnet of

Mar, claimed to have done by 11 June 1297 and is related above under

the castles of Urquhart and Duffus. Earl William's son,

Alexander, was still in the Tower of London as a prisoner with Edward

Balliol, the future king of Scotland, on 12 December 1297.

It seems likely that in 1303 Earl Gratney was

holding Kildrummy castle for the king when he visited in October 1303,

as he always seems to have been on good terms with King Edward.

However, nothing more is heard of him and he must have died soon before

September 1305 when the king wrote to his loyal baron, Earl Robert

Bruce of Carrick (d.1329), instructing him to put someone he could trust in

command of the Chastel de Kyndromyn. This was no doubt done as

Bruce was considered a good guardian for the new earl of Mar, the

underage Donald, who was also Robert's nephew. Six months later

Bruce and his trustworthy captain of Kildrummy rebelled to the great

fury of King Edward. Bruce sent his queen and her ladies to the

castle under the protection of Earl John of Athol and his own brother,

Neil. As a consequence the king sent his son, Prince Edward of

Caernarfon, to besiege the fortress. On hearing of this the

ladies fled to Ross, leaving a garrison in the castle which the prince

came up against in August. After a brief siege the fortress

surrendered before 13 September 1306. According to Barbour's

tales about Bruce written some 2 generations later, Kildromy castle

was attacked by Prince Edward supported by the earls of Gloucester and

Hereford and was betrayed by a blacksmith called Osbern who set fire to

the hall. The resulting inferno spread to the gatehouse and the

castle, with its walls embattled both within and without, was forced to

capitulate. The garrison commander, Neil, the brother of King

Robert Bruce, and others of the garrison, were then executed as they

had broken their fealty to their king, Edward I. Before Prince

Edward withdrew, he slighted the castle by throwing down ‘all a

quarter of Snawdoune, right to the earth, that tumbled down'.

This presumably was what is now known as the Snow tower - then it was

obviously the Snowdon tower - Snowdon being another name for Stirling

as well as a mountain in Wales.

The fortress was obviously rebuilt, probably after

Bruce secured the north in 1308. Certainly it remained loyal to

the Bruces after Edward Balliol's victory at Dupplin Moor on 12 August

1332, when its castellan was Christina Bruce, the widow of Earl Gratney

and mother of Earl Donald of Mar who fell in the battle.

Christina was besieged in the castle during 1335 by Balliol forces

under Earl David Strathbogie of Atholl. The siege was raised by

her third husband, Andrew Morray (d.1338), coming to her rescue and defeating and

slaying Earl David at the battle of Culblean. Kildrummy castle

then remained in Christina's hands until her grandson, Earl Thomas of

Mar (1330-74), came of age, probably around 1351. Christina died

in January 1357.

Earl Donald obviously led an interesting life.

When captured - probably with Bruce's royal family when Kildrummy was

besieged - the young earl was taken to England and detained by King

Edward in Bristol castle. There the king decreed that because of

his tender age he should be unfettered and allowed to play in the

castle garden, watched over by a trustworthy man so that he should not

escape. Later his custody was passed to the bishop of Bath, who

was initially ordered to provide him with a master and a companion and

then to take him into his own household. He obviously liked his

life in England, for when at Michaelmas 1314 he was allowed to return

home as part of the armistice after Bannockburn, Donald got as far as

Newcastle, before deciding he preferred England and returning to the

south. In 1319 he had a safe-conduct from Edward II to visit

Scotland from July until Christmas. He is next found fighting at

Boroughbridge for his king, Edward II, in March 1322 and that October

at Byland against his uncle, King Robert the Bruce. In 1326 he

was keeper of Bristol castle, but left England with the overthrow of

his king and returned to Scotland. In 1327 he commanded a wing of

the Scottish army that invaded England in an attempt to restore King

Edward II to his English throne. Five years later he is said to

have invited Edward Balliol (d.1364) to Scotland, but being regent of the young

King David II, felt compelled to give battle on his ward's behalf and

was killed with much of the nobility of Scotland at Dupplin Moor on 12

August 1332. He left a young son, Thomas, who was aged about

2. Donald's widow, Isabella Stewart, would appear to have held

Kildrummy castle and the wardship of her son until her death in January

1348, when the custody was passed to her then husband, William

Carsewell. Earl Thomas appears of age and lord of Kildrummy

castle in 1351.

In 1361, when a pestilence had driven King David II

(d.1371) towards the north of Scotland, the king and earl fell out with the

result that David seized Kildrummy castle and gave it to the keeping of

Sir Walter Moigne. The castle was still in his hands in 1364 even

though Thomas had, according to a later chronicle, promised to pay

£1,000 for its return when he made his peace with the king.

The chronicle seems to have been in error, for in 1364 Thomas paid the

king £666 13s 4d or 1,000m and no doubt had his castle

returned. The reason for the falling out was likely the close

links the earl maintained with England and an agreement he entered into

with King Edward III on 24 February 1360. This stated that he would

support the king of England in his wars except against the king of

Scots. His support was bought for the sum of 600m

(£400) yearly. However, he was to receive £600 yearly

if he lost his Scottish lands as a result. This no doubt explains

Thomas' ability to find 1,000m in 1364. Thomas had regained

Kildrummy castle by 20 August 1368 when he sealed a charter

there. As a committed Anglophile he repeatedly received safe

conducts in going to England, the last one being in October 1373.

When Earl Thomas died childless before 21 June 1374,

Kildrummy castle passed via his sister, Margaret, to Earl William

Douglas (d.1384). From him the castle passed to his son Earl

James who was killed at the battle of Otterburn on 16 August

1388. Again his heir was his sister, Isabel Douglas, and she took

Kildrummy to her husband, Malcolm Drummond, the brother-in-law of King

Robert Stewart III of Scotland (1390-1406). Malcolm appears to have

been murdered in the Highlands in 1402 when his nephew, the duke of Rothesay, was murdered in Falkland castle,

and between 1 and 9

December 1404 his widow married Alexander

Stewart, who thereby became earl of Mar for his lifetime only. On

19 September 1404,

Alexander stood before the gates of Kildrummy castle stating that he

delivered that fortress to the countess with the papers, silver plate

and all other furnishing within the castle with a good heart for her to

dispose of them as she pleased. Whereupon the lady, with the keys

to the castle in her hand, upon mature advice, took Alexander as her

husband and in free marriage gave to him Kildrummy castle and its

appurtenances, the earldom of Mar, the lordship of Garrioch, the

baronies of Strathalveth and Creichmount, Down, Buck and Cabrach, an

annual rent of 200m (£133 6s 8d) from Haddington, the forest

of Jedburgh and all her other lands previously held by her parents

within Scotland. His coup d'etat in seizing the castle and

earldom was recognised by the king later that autumn when he came to

Perth to arbitrate between Alexander and the Erskines, who had coveted

the land of Mar. Seven years later in 1411, the earl of Mar

halted the advance of Donald of the Isles [Urquhart] at the battle of

Harlaw before he reached Kildrummy castle.

On Earl Alexander's death in 1435, Kildrummy was taken

over by James I. Even this did not go without hitch, for in 1442

Sir Robert Erskine took the castle and held it until 1447 before

relinquishing it to the king in exchange for Alloa castle on condition

that he should have half the earldom of Mar as would be adjudged to him

in parliament on the king coming of age. The dispute was still

rumbling on in 1449, but the castle remained with the king.

During the king's tenure the castle was repaired with over £15

being spent on masonry work which included repairing a stone fireplace,

retiling the chapel roof and making 4 great iron bars for the castle

gates. Further repairs occurred in 1451 costing over £13

and in 1464 the Burges and Maldis towers were recovered - presumably

with lead - at a cost of well under £10. However £280

was spent between 1468 and 1471 on undetailed repairs to the fabric of

the castle.

In 1507 the Crown granted the fortress to Lord

Elphinstone. On 18 June 1555, John Strachan of Lenturk in his own

hand recorded that he had been forgiven by Queen Mary for his

‘treasonable burning of the place of Kyldrimmy' and other

offences. In 1654 the castle was captured by Cromwellian forces

under Colonel Morgan, while it was apparently burned by retreating

Jacobites around 1689-90. Finally the castle became the

headquarters of the earl of Mar's abortive Jacobite rising of

1715. After this the fortress appears to have been systematically

demolished and by 1724 was described as ruinous. The last parts

of the Snowdon tower only collapsed in 1805.

Description

Kildrummy castle is shield shaped in plan with 6 towers of varied

forms. The flat side of the castle overlooks the steep ravine of

the Culsh Burn known as the Back Den. In front of the castle was

a massive ditch, 80' across and 15' deep, which is best preserved to

the east. There is also a large berm, 50', which is similar to that

found at Inverlochy. It has been suggested that immediately

within this ditch was a low outer wall which can only now be seen

running north-east from under the Warden Tower to the ditch. Yet no

foundations or traces of defences were uncovered elsewhere along the

ditch top by excavation in the 1950s.

Opposite the burn, the castle walls come to a point

which is defended by a standard, 30' diameter, twin towered gatehouse

forming a block 70' across by 60' long. Although externally

¾ round, internally the towers were D shaped, both having

rectangular extensions to the rear which were entered from the gate

passageway. As such both were standard guardrooms. However,

they were separated from the round towers via crosswalls with each

containing a doorway and now only the base of apparently rectangular

windows. It therefore seems possible that the guard chambers are

additions to the original gatehouse plan. To support this

argument the inner walls of the gatehouse were much thinner than the

external ones. If this assumption is correct then the original

gatetower, consisting of just the two forward towers would have been

akin to the great gatehouse at White Castle in Gwent, built in the

1230s. Access to the upper floors of the towers was possibly only

gained from the wallwalks or an external stair. Garderobes in the

adjoining curtains were apparently reached via passageways in the

thickened junctions between the gatehouse and its two adjoining

curtains. It appears possible that both towers were stone vaulted

like those at Urquhart, though the rear rectangular guardrooms had

wooden flooring.

Excavation shows that the gatehouse was burned and

then rebuilt and finally demolished when even the foundations were

grubbed up to the north. This therefore confirms the historical

report of the structure's burning in 1306. In 1925 the original

herringbone floor of the east gatetower was uncovered and found on the

floor were the skeletons of 2 young men; one beheaded and one

with his skull crushed in. How these relate to the history of the

castle is unknown.

The clay built wall found in front of the gatehouse

has been interpreted as a quick defence thrown up while rebuilding work

on the gatehouse was in progress. As such the external wall

probably dates to the second half of the reign of Robert the Bruce

(1306-29) as does the final style of the gatehouse. Presumably

the plan of the early fourteenth century gatehouse is similar to its pre-1306

predecessor. It also appears that the towers join onto the older

curtain wall of the enceinte and therefore postdate this.

Set before the gatehouse was a small passageway

barbican which added a drawbridge and pit to the defences. The

structure definitely butts against the gatehouse and therefore

postdates it. The drawbridge mechanism was operated from an upper

room, of which only a few steps, butting against the gatetower to the

south-west, that once led up to it now remain. It is therefore

apparent

that before this fourteenth century barbican was built the castle entrance was

protected solely by gates. There is no trace of a

portcullis. As such the implication is that the gatehouse design

is very early.

The gatehouse is linked to two flanking towers in

the enceinte to north and south by two irregular stretches of curtain wall

which predate the towers. These 2 mural towers, known as the

Maule and Brux towers, were 35' diameter D shaped structures with

polygonal interiors and thinner interior walls. They do not project

beyond the curtain as boldly as the other 4 towers and have stairwells

built into the acute angles with the curtain walls. Mortar

analysis also concludes that they date to a different building phase

than other parts of the castle. In style these towers resemble

those found at Caergwle castle which are dated, possibly with

overconfidence, to the period 1277-82.

The Brux Tower is heavily damaged, but enough

remains to show that the beams of the first floor rested on a 1½'

offset. The south-west corner of the tower has also been modified when a

possible spiral stair was added. At this level there was a loop

to the east and others to the north and south covering the base of the curtain,

but all are much damaged. The base of the tower rests on a fine

sloping plinth while the ashlar of the tower is also markedly superior

to that of the adjoining curtains. The Maule Tower has been more

reduced in height that its companion to the north-east, but what remains is

better preserved. This shows that the 3 loops were long crossbow

loops without oillets or sighting slits. As such they could be

late twelfth century as much as thirteenth century.

From these two flanking towers their respective

curtains ran back to the two major towers of the site - the Warden Tower and the Snowdon Tower - a large round tower keep.

The Warden Tower, at the north apex

of

the site, was 40' in diameter and has 8' thick walls. It is of a

totally different design to the other towers of the castle, being

totally circular, but with a similar sloping plinth. It was

entered at the ground floor level next to an unconnected spiral stair

in the gorge wall that led to the higher floors. Within the tower

was a simple loop to the north-west. This room is supposed to

have been

the prison. The first floor had 4 loops, similar to those in the

south and east towers, the south pair of which cover the

curtains. A

garderobe was also available set in the thickness of a passageway in

the curtain to the south-east. The 2 floors above were definitely

residential, being equipped with fine two light windows and fireplaces.

The curtain ran south-west from the Warden Tower to the keep

or Snowdon Tower at the western apex of the castle. This was bigger

than the other towers, being 50' in diameter with walls 12' thick at

the base. Presumably the tower was originally also taller than

the rest. In 1724 the keep was described as seven vaulted storeys

each one about 30' high, which would have made a tower 210' high!

The survey went on to state that about 8' up (2 chairs in height) there

was a stepped plinth 1½' deep ‘with several doors opening

to it from the wall'. Apparently this was a hall. The wall

was then stated (wrongly) to be 18' thick and contained numerous

spacious mural chambers and a mural gallery with loops in it. If

we were to assume that the writer's 18' was actually a more reasonable

10', the possible thickness of the wall above the plinth, then his

tower would have been a more reasonable 110' high, with storeys coming

in at a much more reasonable 16' instead of 30'. If there was a

passageway right around the keep, which would have taken a minimal of

3' out of the 10' thick wall, then the tower's collapse becomes more

understandable. The central rectangular well (excavated to a

depth of 24' feet in the 1950s and still proceeding downwards into the

natural rock) was serviced via holes left in the vaults above.

The top storey of the keep was already ruinous and grass-grown in 1724,

while there was a breach in the tower to the NE. The survey also

found a second well in the ward that was 200' (recte 120') deep.

There was also claimed to be a vaulted passageway 100s of yards long

that two mounted knights could ride down - but unfortunately it was

already collapsed! Further the ‘square' castle ward was

about a mile in circumference(!) and opened to the south where there were 3

or 4 gates of which some iron ones still remained. Presumably

these gates included one in the barbican and one at the beginning and

one at the end of the main gate passageway.

The curtain ran south-west from the Warden Tower to the keep

or Snowdon Tower at the western apex of the castle. This was bigger

than the other towers, being 50' in diameter with walls 12' thick at

the base. Presumably the tower was originally also taller than

the rest. In 1724 the keep was described as seven vaulted storeys

each one about 30' high, which would have made a tower 210' high!

The survey went on to state that about 8' up (2 chairs in height) there

was a stepped plinth 1½' deep ‘with several doors opening

to it from the wall'. Apparently this was a hall. The wall

was then stated (wrongly) to be 18' thick and contained numerous

spacious mural chambers and a mural gallery with loops in it. If

we were to assume that the writer's 18' was actually a more reasonable

10', the possible thickness of the wall above the plinth, then his

tower would have been a more reasonable 110' high, with storeys coming

in at a much more reasonable 16' instead of 30'. If there was a

passageway right around the keep, which would have taken a minimal of

3' out of the 10' thick wall, then the tower's collapse becomes more

understandable. The central rectangular well (excavated to a

depth of 24' feet in the 1950s and still proceeding downwards into the

natural rock) was serviced via holes left in the vaults above.

The top storey of the keep was already ruinous and grass-grown in 1724,

while there was a breach in the tower to the NE. The survey also

found a second well in the ward that was 200' (recte 120') deep.

There was also claimed to be a vaulted passageway 100s of yards long

that two mounted knights could ride down - but unfortunately it was

already collapsed! Further the ‘square' castle ward was

about a mile in circumference(!) and opened to the south where there were 3

or 4 gates of which some iron ones still remained. Presumably

these gates included one in the barbican and one at the beginning and

one at the end of the main gate passageway.

The remains of the keep have another fine sloping

plinth that appears similar to that found on the other 3 towers, but

above this most is now gone. It appears to have been entered via

a 9' wide room set in the north curtain connecting it to the much later

Elphinstone tower which lay against the great hall and was serviced by

a suite of garderobes set in the curtain to the south. The hall is

integral with the north curtain and therefore also the 2 towers on either

end of it. In 1724 the hall was described as 60 paces by 15, with

large arched windows and called Barnet's Hall. Surprisingly the

hall had spiral stairs in both its north and south corners. The west window

in the north wall is best preserved and shows it was a 2 light window over

6' high and with stone benches in the embrasure. The original

solar to the hall was rebuilt as the Elphinstone Tower in the sixteenth century -

the differences in masonry are readily apparent. A kitchen lay at

the east end of the hall, but this is mostly reduced to foundations.

Between this and the Warden Tower was a postern that led down to the

burn. At some later date a row of buildings were built along the south face of the hall, obscuring the earlier windows.

The east wall of the hall and these buildings seems

contemporaneous with the castle chapel which runs from the hall due east

through the curtain wall. This is a most curious structure of at

least 3 phases. Excavation suggests that the initial church may

possibly have predated the castle. This was then built over by

the castle curtain wall and the base of an apse or tower added to the east

end. The foundations of this clay laid semi-circular structure

are only 2' high, while the internal walls of this chapel are only 3'

thick. The castle curtain wall was has been broken through and

the chapel east end built, not quite exactly, on the earlier

foundations. This work has 3 finely carved lancet windows and is

all done in ashlar similar to that of the north curtain and towers.

However there is no plinth, but there is a single string course

immediately beneath the windows. There is also a first floor

gallery in the north wall, now collapsed, that apparently led to a

garderobe. This suggests a change of use for the chapel - maybe

it was made into a later hall as seems to have happened at Lochleven

castle. Excavation in the 1950s showed the internal north wall of the

chapel was joined to the hall wall. Despite the 1724 claim that

bones had been dug up within the ruins of the church and its church

yard, no evidence of such was found during recent excavations.

It is clear from this resume that the keep and

Warden Tower are of different designs and builds from the D shaped

towers. The design and style suggests that they are later.

The north curtain wall between these two towers would appear to be of a

similar date as it has the same sloping plinth as found elsewhere and

is ashlar built, just like the 2 towers. Taken together this

suggests that the castle began its life as a ringwork castle built on

the edge of a plain with its back to the burn. It subsequently

had a gatehouse added and then the two flanking towers, Brux and

Maules. Finally the north curtain was built with the internal

buildings and the 2 great towers, probably on the site of whatever it

was that Prince Edward threw down in 1306.

As ever we have no idea when this castle was founded

and for whom. Presumably it was commenced by the earls of Mar who

held the district from at least 1147, in the form of Earl Morggan

(bef.1130-78/83) and his descendants. The initial castle

seems to have been a plain polygonal enclosure of which the coursed

rubble of the east, west and south curtains remains. This was built at the

same time as the ditch was dug. Traces of earlier walling may

still be seen under the Snowdon and Warden towers according to the

report of the 1950s excavations.

The second phase consisted of adding towers and the

gatehouse to the enceinte, probably at different times. Finally

the ashlar keep, or Snowdon Tower, together with the north curtain,

Warden Tower, hall and projecting chapel end were added or rebuilt

after

1306. This was in a better quality of ashlar again.

Therefore the structures associated with this phase are united in

having squared ashlar facing as their construction, though of course

the local stone used in the construction of the castle would have been

used in a similar manner. Of course, such a similar manner of

construction does not necessarily prove a similar time of

building. The covered passage down to the Culsh Burn probably

originates in this phase too. Throughout the castle, roughly

dressed masonry suggests considerable rebuilding. Possibly this

dates to the royal repairs recorded in the fifteenth century.

As the gatehouse was rebuilt, probably after the

siege of 1306 when it was recorded as destroyed by fire, it is logical

that the initial plan and the Brux and Maule towers were all built

before this. If the above reconstruction is accepted as correct,

the first three phases of the castle are all dateable to the twelfth or thirteenth century. The castle so described has remarkable similarities to

other Scottish enclosure castles like Dirleton, Bothwell, Inverlochy,

Lochindorb and even Urquhart. The Snowdon Tower was obviously

standing when the siege occurred in 1306, although what is most likely

the replacement after ‘the quarter called Snowdon' was thrown

down may follow a totally different plan. In Wales castles

bearing resemblance to some of these structures include Caergwle and

Flint, one possibly and the other certainly

built in the 1270s.

After 1507 Lord Elphinstone converted the solar

block on the west of the great hall at Kildrummy into a towerhouse.

It was probably at the same time a narrower entrance was inserted into

the gatehouse, which was also strengthened against artillery by having

its basements vaulted, just as was done at Urquhart.

Simultaneously the courtyard, gate passageway and drawbridge pit were

cobbled over and probably the barbican side gate was blocked. The

freestanding kitchen block or bakehouse cannot be fitted easily to this

sequence and is incomplete in its present form, but presumably post

dates that built into the north curtain and therefore dates to the

Elphinstone period. Other undated structures include the now

levelled, lean-to timber structures built against the curtain walls to

the west of the bailey. This phase included the addition of a range

of three rooms along the south wall of the great hall, possibly after it

was abandoned, since a chimney was inserted into the westernmost window

opening. Much of this could date to the eighteenth century.

Why not join me at Kildrummy and other Great Scottish Castles this Spring? Information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2016

Paul Martin Remfry

It was William's son, Earl Donald (1281-97), who was

lord of Kildrummy while King Edward I stayed there. Sometime after 1266,

when Earl Malcolm of Fife died, Earl William married his widow,

Helen. She appears not to have been the Susannah Ferch Llywelyn

ab Iorwerth of Wales who had given Malcolm two children, despite

Wikipedian claims to the contrary. In any case, between 1266 and

1297, Helen bore Donald 3 surviving children, one of whom, Isabella,

bore Robert Bruce, later to be king, a daughter called Marjorie.

She died in 1296, possibly while giving birth. The marriage and

perhaps personal inclination tied Donald solidly to Bruce's claim to be

king of Scotland and he was often found working in harmony with that

family. Despite this, he broke with Bruce and joined the 1295

rebellion and was amongst the barons taken at Dunbar in April

1296. This was followed, on 10 July, by William performing homage

to the king at Montrose when King John Balliol surrendered his

kingdom. On 23 June 1297, Donald promised to serve King Edward I in

France and consequently received permission to return to

Scotland. He was back in the country, but dead by 25 July.

The manner of his death is unknown. However he may have died

putting down the rebellion of Andrew Moray, as his son, Earl Gartnet of

Mar, claimed to have done by 11 June 1297 and is related above under

the castles of Urquhart and Duffus. Earl William's son,

Alexander, was still in the Tower of London as a prisoner with Edward

Balliol, the future king of Scotland, on 12 December 1297.

It was William's son, Earl Donald (1281-97), who was

lord of Kildrummy while King Edward I stayed there. Sometime after 1266,

when Earl Malcolm of Fife died, Earl William married his widow,

Helen. She appears not to have been the Susannah Ferch Llywelyn

ab Iorwerth of Wales who had given Malcolm two children, despite

Wikipedian claims to the contrary. In any case, between 1266 and

1297, Helen bore Donald 3 surviving children, one of whom, Isabella,

bore Robert Bruce, later to be king, a daughter called Marjorie.

She died in 1296, possibly while giving birth. The marriage and

perhaps personal inclination tied Donald solidly to Bruce's claim to be

king of Scotland and he was often found working in harmony with that

family. Despite this, he broke with Bruce and joined the 1295

rebellion and was amongst the barons taken at Dunbar in April

1296. This was followed, on 10 July, by William performing homage

to the king at Montrose when King John Balliol surrendered his

kingdom. On 23 June 1297, Donald promised to serve King Edward I in

France and consequently received permission to return to

Scotland. He was back in the country, but dead by 25 July.

The manner of his death is unknown. However he may have died

putting down the rebellion of Andrew Moray, as his son, Earl Gartnet of

Mar, claimed to have done by 11 June 1297 and is related above under

the castles of Urquhart and Duffus. Earl William's son,

Alexander, was still in the Tower of London as a prisoner with Edward

Balliol, the future king of Scotland, on 12 December 1297.

The curtain ran south-west from the Warden Tower to the keep

or Snowdon Tower at the western apex of the castle. This was bigger

than the other towers, being 50' in diameter with walls 12' thick at

the base. Presumably the tower was originally also taller than

the rest. In 1724 the keep was described as seven vaulted storeys

each one about 30' high, which would have made a tower 210' high!

The survey went on to state that about 8' up (2 chairs in height) there

was a stepped plinth 1½' deep ‘with several doors opening

to it from the wall'. Apparently this was a hall. The wall

was then stated (wrongly) to be 18' thick and contained numerous

spacious mural chambers and a mural gallery with loops in it. If

we were to assume that the writer's 18' was actually a more reasonable

10', the possible thickness of the wall above the plinth, then his

tower would have been a more reasonable 110' high, with storeys coming

in at a much more reasonable 16' instead of 30'. If there was a

passageway right around the keep, which would have taken a minimal of

3' out of the 10' thick wall, then the tower's collapse becomes more

understandable. The central rectangular well (excavated to a

depth of 24' feet in the 1950s and still proceeding downwards into the

natural rock) was serviced via holes left in the vaults above.

The top storey of the keep was already ruinous and grass-grown in 1724,

while there was a breach in the tower to the NE. The survey also

found a second well in the ward that was 200' (recte 120') deep.

There was also claimed to be a vaulted passageway 100s of yards long

that two mounted knights could ride down - but unfortunately it was

already collapsed! Further the ‘square' castle ward was

about a mile in circumference(!) and opened to the south where there were 3

or 4 gates of which some iron ones still remained. Presumably

these gates included one in the barbican and one at the beginning and

one at the end of the main gate passageway.

The curtain ran south-west from the Warden Tower to the keep

or Snowdon Tower at the western apex of the castle. This was bigger

than the other towers, being 50' in diameter with walls 12' thick at

the base. Presumably the tower was originally also taller than

the rest. In 1724 the keep was described as seven vaulted storeys

each one about 30' high, which would have made a tower 210' high!

The survey went on to state that about 8' up (2 chairs in height) there

was a stepped plinth 1½' deep ‘with several doors opening

to it from the wall'. Apparently this was a hall. The wall

was then stated (wrongly) to be 18' thick and contained numerous

spacious mural chambers and a mural gallery with loops in it. If

we were to assume that the writer's 18' was actually a more reasonable

10', the possible thickness of the wall above the plinth, then his

tower would have been a more reasonable 110' high, with storeys coming

in at a much more reasonable 16' instead of 30'. If there was a

passageway right around the keep, which would have taken a minimal of

3' out of the 10' thick wall, then the tower's collapse becomes more

understandable. The central rectangular well (excavated to a

depth of 24' feet in the 1950s and still proceeding downwards into the

natural rock) was serviced via holes left in the vaults above.

The top storey of the keep was already ruinous and grass-grown in 1724,

while there was a breach in the tower to the NE. The survey also

found a second well in the ward that was 200' (recte 120') deep.

There was also claimed to be a vaulted passageway 100s of yards long

that two mounted knights could ride down - but unfortunately it was

already collapsed! Further the ‘square' castle ward was

about a mile in circumference(!) and opened to the south where there were 3

or 4 gates of which some iron ones still remained. Presumably

these gates included one in the barbican and one at the beginning and

one at the end of the main gate passageway.