Falkland

The origin of Falkland castle is unknown. It may

have been commenced by the Canmore kings, but the manor was given by

King Malcolm IV (1153-65) to Earl Duncan McDuff (d.1204) when he

married the king's kinswoman, Ela, in 1160. The Fife lands

included Strathmiglo, Falkland (Faleklen), Kettle, Rathillet and

finally Strathbran in Perthshire. According to popular opinion

the MacDuff earls constructed an ubiquitous ‘hunting lodge' at

Falkland sometime in the twelfth or thirteenth century. Sadly

there is no evidence to back such a presupposition.

Falkland remained with the MacDuffs until the death of Earl Duncan in

1353. At this point King David II (1329-71) seized Falkland castle

and Fife to the detriment of Duncan's only surviving child, Isabella

(d.bef.1396). Despite popular opinion since the fifteenth

century, Isabella never married Earl William Ramsay of Fife

(d.1361). He was simply made earl by the arbitrary power of King

David II (d.1371).

Long before the events of the 1350s, during the fighting between the

supporters of David Bruce (d.1371) and Edward Balliol (d.1364), Earl

Duncan of Fife (d.1353) had changed his allegiance several times.

He fought for Bruce at Dupplin Moor on 12 August 1332, where he was

captured and promptly changed sides. He then crowned Edward

Balliol at Scone on 24 September 1332, as was the ancient right of the

earls of Fife. Subsequently he was captured the same year when

Perth fell to an assault by the Brucites in October. Following a

pattern, Fife promptly changed sides again although Perth was retaken

by Balliol the next year. The same year, on 19 July 1333, Duncan

was captured anew, this time by Edward III (1326-77) at the battle of

Halidon Hill. It is certain that a castle was built by this time

as in 1337, Andrew Moray of Bothwell castle

(d.1338) swept south from the highlands, taking the bulk of the castles

loyal to King Edward Balliol (d.1364); one of these was the keep or

tower of Falkland (turre de Faulkland).

Released and returned to Scotland, Earl Duncan eventually joined King

David Bruce (d.1371) in his invasion of England which came to grief

outside Durham at Neville's

Cross on 12 October 1346. Captured by the English again he was

condemned as a traitor, but was released on agreeing to pay a ransom of

£1,000. He died 7 years later in 1353, leaving the fate of

Fife and Falkland castle in the balance.

Falkland castle and Fife were probably seized into the king's hands

immediately on the death of Earl Duncan. One contemporary

chronicler states that the land was forfeit to the Crown as the earl

had received the earldom as a male entail after he had murdered one

Michael Beaton in the time of Robert the Bruce (1306-29). However, Duncan's

daughter, Isabella (d.bef.1396), contested this forfeiture, at first

from England where she lived with her husband, William Felton (d.1358) and

after his death from Scotland where she sought the aid of King David's

heir, his nephew, Earl Robert Stewart of Menteith (d.1390), the king's

Steward and heir apparent. Despite this, the king, in March 1358,

arbitrarily awarded Fife to his favourite, William Ramsay. Ramsay

was dead by 1361, but even before this time the Steward managed to

overturn this decision and late in 1359 Fife was adjudged to

Isabella. In the year between 21 July 1360 and 20 July 1361, she

married Robert Stewart's second son, Walter. Just as the fate of

Falkland castle finally seemed secure, Walter promptly died in late

1362, leaving Isabella a widow for the second time. At this

moment the king pounced, marrying Isabella to his friend, Thomas Bisset

on 10 January 1363. This act illegally debarred the marriage

entrail which meant that Fife and its castles should have passed to one

of Walter Stewart's younger brothers as male heir. Once again the

marriage proved short lived and by 17 April 1366, Isabella was a widow

once again. This time her widowhood was to prove permanent and

sometime in the Autumn of 1370 she resigned the earldom of Fife into

the king's hands. At this point the king simply granted Fife to

his mistress' brother, John Dunbar (d.1392), who promised to pay

Isabella a lifetime annuity of £145 pa. Despite later

claims to the contrary, she did not marry her supplanter.

However, within 6 months all was uncertain again when King David II

suddenly died on 22 February 1371, leaving his elder nephew the throne

as King Robert II (1371-90).

With King David gone, Isabella promptly reneged on her agreement with

John Dunbar and on 30 March 1371, formally recognised Robert Stewart's

second son, Robert (d.1420), as earl of Fife under the terms of the

previous entails which had twice been set aside by the arbitrary

judgement of King David II. Not wishing a fight with the powerful

Dunbars the new King Robert II granted them much of the earldom of Moray

(without Urquhart castle), Annandale with Lochmaben castle

and the Isle of Man in compensation. In the meantime, it was

Isabella of Fife and not John Dunbar as earl of Fife, who seems to have

crowned King Robert II at Scone. One thing never commented upon

in this confusing affair is the fate of Isabella's 4 or 5 children with

her first husband, the Englishman William Felton (d.1358). The

brothers, John and Duncan Felton, second great grandsons of King Edward I (1272-1307) as well as fourth great grandsons of King Alexander II (1214-49) and Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth of Wales (1172-1240) and his wife Joan Plantagenet (d.1237) the daughter of King John (1199-1216), never had a look in on their Scottish inheritance, probably as they were seen as adherents of the English king.

Earl Robert Stuart (d.1420) of Menteith and now Fife was the second son

of King Robert II (1371-90) and went on to be made duke of

Albany. The earldom of Fife now became just another of his many

titles - Menteith, Buchan and Athol being his other earldoms.

Robert was appointed ‘Guardian of Scotland' by his ailing father

the king during the 1380s in preference to his elder brother John, who,

although later crowned as King Robert III (1390-1406), was in poor

health. Duke Robert was then the major power as regent of

Scotland for the next 34 years. During this time Falkland castle

was one of his main residences, although there is no record of him

repairing or upgrading it.

In late 1401, supporters of Duke Robert and Earl Archibald

Douglas (d.1424), captured King Robert III's eldest son, Duke David of Rothesay, and took him into custody at St Andrews castle,

which he was preivously besieging.

He was then imprisoned at Albany's Falkland castle, allegedly in the

well tower, in dreadful conditions until he died on 26 March.

Despite this, Albany was exonerated for his demise, although it was

alleged that Rothesay had been starved to death, rather than

‘departed this life... by divine providence and not otherwise' as

the official judicial report would have it. Just over a year

later in May or June 1403, Duke Robert of Albany made a rousing speech

to fire the surviving aristocracy of Scotland, after the disastrous

defeats of 1402, to fire the nation into arms in a harangue similar to

that made by Bruce before Bannockburn. He vowed, ‘to God

and St Fillan that if I am spared I shall be there on the appointed day

even if no one comes with me save my boy Patrick as rider of my

warhorse'. The Scottish nobles, heartened by this grand display

of ardour vowed to join in the enterprise of marching on the

‘little tower' of Cocklaws to relieve it from English

attack. By this point it seems plain that Albany knew that

England was collapsing into civil war and that there was no chance of

meeting an enemy army at Cocklaws. Thus the lieutenant of

Scotland won an easy victory for the hearts of his subjects with little

risk to his 64 year old self.

King Robert III,

apparently fearing that his younger son, James (1394-1437), would go

the same way as the duke of Rothesay, decided to send him to the apparent safety of France in

1406. The attempt failed and the young Prince James was captured

on 22 March 1406 and spent the next 18 years of his life in English

captivity - his father, King Robert, dying on 4 April the same

year. Albany therefore remained regent for the captive boy king

until his death in 1420 in Stirling castle.

At this point his son, Duke Murdoch of Albany (1362-1425), took his

father's place as regent. Falkland castle therefore remained

central to the power Albany had over Scotland.

Under the Murdoch regency James I was finally ransomed and gained his

freedom in April 1424. In August the Scottish army in France was

all but annihilated at the battle of Verneuil and James I moved

decisively against Duke Murdoch Stewart of Albany and his family.

Murdoch was imprisoned at St Andrews castle and then Caerlaverock, while his wife was taken to Tantallon.

Falkland castle with the rest of Albany's estates were confiscated when

in Stirling castle the earl and his sons, together with Earl Duncan of

Lennox, were tried over 2 days (24-25 May 1425) and found guilty of

treason. On news of this Albany's youngest son, James Stewart

(d.1429), attacked Dumbarton and killed the castle constable, but his rising proved abortive and his family were executed before Stirling castle. With this Falkland castle became just another castle in Crown hands.

The castle history might have ended here, if it were not for the fact

that in 1449 King James II (d.1460) married Mary of Gueldres and

granted her many lands and fortresses, one of which was Falkland.

Consequently, between 1453 and 1460, she began to convert the castle

into a palace with a suite of comfortable apartments set in the current

quadrilateral style. Royal status was also granted to the burgh

of Falkland in 1458. This meant that the burgers could elect

officers for justice and hold weekly markets as well as a yearly

fair. The building work came to end with her early death in

1463. With this the castle again became a backwater, even though

the surrounding forest offered good game and was not too far from

either Edinburgh or Stirling.

King James IV (1488-1513) took the new Falkland palace in hand around

1511 and began to convert what he found into a proper Renaissance

palace which included a great hall. By 1513 the north and south

ranges had been upgraded and the east range was under construction when

James was killed at the battle of Flodden on 9 September. This

halted construction for 15 years during the minority of James V

(1513-42), although the young prince did stay here during the regency

of Duke John Stewart of Albany (d.1536). In 1528 he fled the

palace dressed as a groom and joined his mother, Margaret Tudor

(d.1541), at Stirling castle. He soon appointed William Barclay as keeper of Falkland palace and later completed the east range.

By 1537, when King James V (1513-42) married Madeleine Valois (d.1537),

the daughter of King Francis I of France (1515-47), the upgrading of

Falkland palace was finished and given to the new queen as part of her

dower. This did not stop further improvements and between 1537

and 1541 the new twin towered gatehouse was built and the east and

south ranges remodelled, while a royal tennis court was added in 1539,

the oldest surviving example in the world. From this time onwards

with Edinburgh, Linlithgow, Stirling, Perth and St Andrews,

Falkland palace became one of the major residences of the Crown.

King James V (1513-42) was staying here when informed that his mother

at Stirling castle was dying and he

himself died here on 14 December 1542 after the battle of Solway

Moss. It is likely the original castle had been demolished by

this time.

After James' death at the end of 1542 further work on Falkland palace

ceased, so that a planned western range, to finish the quadrangular

plan, was never built during the long minority of Mary Queen of Scots

(1542-61), although her mother, Mary of Guise (d.1560), was often a

Falkland resident. On Queen Mary's return from France she

obviously regarded Falkland as a favourite palace and between 1561 and

the crisis of 1566 she was often found hawking, riding and playing

tennis there. Her son, James VI (1567-1625), was also often found

in residence, despite 2 attempts on his life there. He later

granted it to his wife, Anne of Denmark (d.1619). When

James became king of England in 1603, he left Scotland, returning north

of the border only the once. His son, Charles I (1625-49), only

visited Scotland the once in 1633 when he stayed for 5 days at Falkland

palace.

Towards the end of the Civil War, Falkland palace was occupied by

Parliamentary troops, who, in September 1654, accidentally burned the

great hall with the north and east ranges. Although the site was

restored by Charles II (1660-85), no king returned to the old palace

which was left to gently moulder.

In 1887 the Third Marquis of Bute (d.1900) purchased Falkland and

started to refurbish the palace in a similar manner to his rebuildings

of Cardiff castle and Castell Coch.

He also excavated the early Falkland castle site with the aim of

discovering the remains of the well tower in which the duke of Rothesay

had been held. When Bute died in 1900 he left the gatehouse,

south range and cross house largely restored.

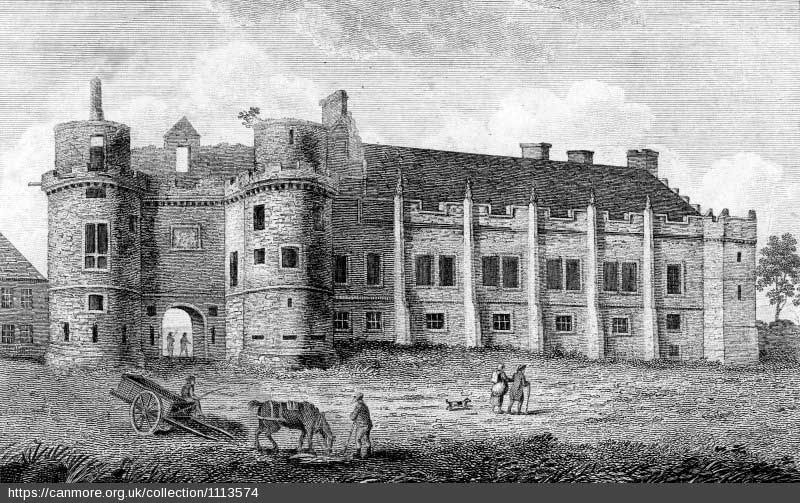

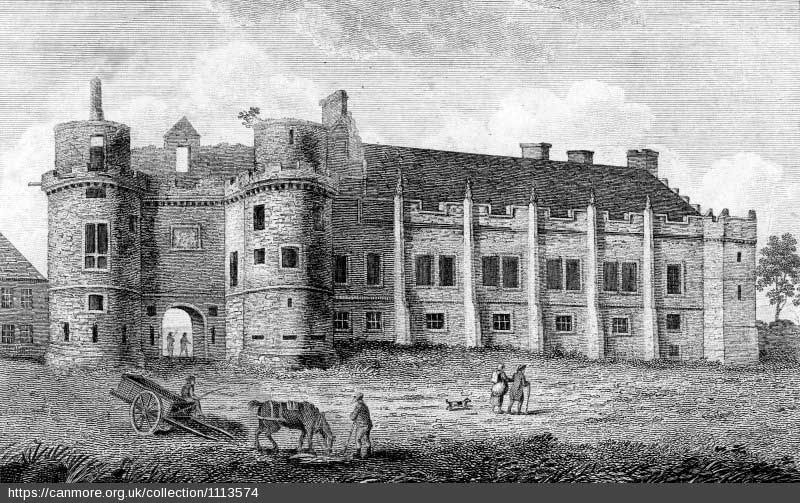

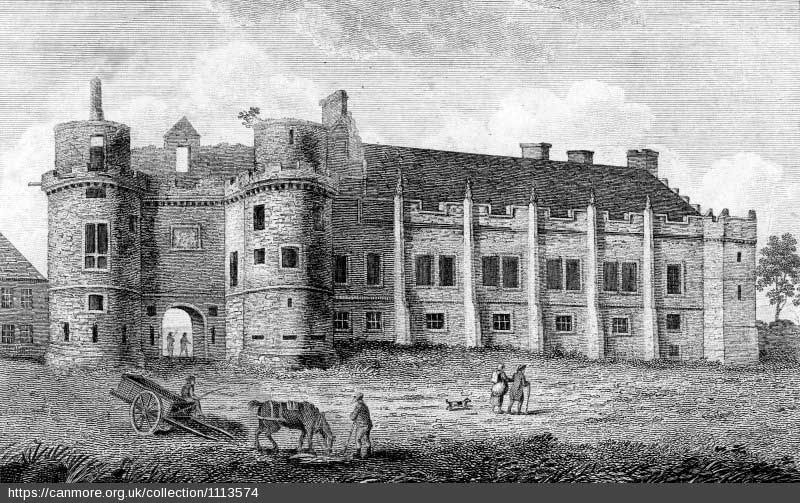

Castle Description

Falkland castle occupied some high ground overlooking the Maspie Burn

to the west. Despite a history that may have begun as early as

the twelfth century, all that is known of the castle or ‘tower'

of Falkland first mentioned in 1337 has been gleaned through 2

excavations, the one in the late 1880s and the other in the

1990s. The first excavation found that the north range had 2

walls to east and west that continued northwards for some 100' and

probably formed the castle ward. This would indicate that

Falkland was originally a castle and not just a tower, there being no

trace of a keep, unless its site lies under the current palace to the

south. That this is likely is confirmed by the fact that the

palace site lies slightly uphill from ‘the castle' site.

At the north end of the rectangular ‘castle' enclosure, about

160' north to south and 50' wide, seem to have been 2 round towers, one

to the north-west, the other to the east. These lie north of the

palace and appear to represent the remains of the castle. On the

east wall, about 20' north of the north range of the palace were found

the buried remains of the foundations of a small rectangular internal

tower. North of this was the north wall and part of the west wall

of a large rectangular structure, possibly a hall. Beyond this,

to the north-east, were the remains of a much thicker curtain wall with

a sewer running through it.

Attached

to the fragment of the

foundations of the east curtain were the slight remains of a half round

drum tower at the north-east end of the enceinte. This was about

25' in diameter and contained a central well shaft. The 1990s

excavation thought that this structure had been 'dismantled and

entirely

restored' by Lord Bute during his excavations in the 1890s. Even

worse, a well head, perhaps of seventeenth or eighteenth century

design, had been introduced into the tower site. Quite clearly

Bute's desire to find the site of Rothesay's incarceration had led to

this rebuilding and insertion. The attached photograph shows the

possible original tower foundations under the Victorian folly of 3

courses of sloping plinth. The faked well head is also visible.

Attached

to the fragment of the

foundations of the east curtain were the slight remains of a half round

drum tower at the north-east end of the enceinte. This was about

25' in diameter and contained a central well shaft. The 1990s

excavation thought that this structure had been 'dismantled and

entirely

restored' by Lord Bute during his excavations in the 1890s. Even

worse, a well head, perhaps of seventeenth or eighteenth century

design, had been introduced into the tower site. Quite clearly

Bute's desire to find the site of Rothesay's incarceration had led to

this rebuilding and insertion. The attached photograph shows the

possible original tower foundations under the Victorian folly of 3

courses of sloping plinth. The faked well head is also visible.

After Bute's work even less remained of the short, less than 20' long,

north curtain, but it appeared to end in a small ¾ round tower

whose shattered foundations appeared to be about 18' in diameter.

Sadly the Victorian work removed all pervious archaeological

layers. Further, Lord Bute was found to have reused stonework

from adjacent medieval buildings to make up a level surface. The

original layout of this ‘castle' and even its original position is therefore open to

question. An angled terrace to the east of the towers marks the

site of a probably seventeenth century building.

Palace Description

The sixteenth, if not the fifteenth century palace was a quadrangular

structure of which the layout of the ranges remain to the north, south

and east sides. The west side originally consisted of a wall with

a lodging built against it. This has now gone as has much of the

north range, leaving mere foundations. The south range was

massively restored by the marquis of Bute, while the east range is

mostly ruined.

Excavation of the east range identified 3 distinct building phases

which dated from the mid fifteenth century to the sixteenth, with a

long gallery having been on the first floor by 1461. As such it

would probably have linked the hall in the north range with the royal

apartments in the south. This in turn would suggest that the

original castle was abandoned before this date and that the outline of

the palace was put in place by James II (1437-60) and his queen, Marie

of Gueldres (d.1463). The south face of the palace is generally

thought to have been ‘late fifteenth century' and therefore their

work as it seems unlikely that James III (1460-88) undertook building

work here. In 1461, 2 rooms were built in the gallery and a new

chamber was added for the queen with a door leading to the pleasure

garden.

James IV (1488-1513) seems mainly to have reconstructed the south

range, incorporating the original (fifteenth century?) rectangular

gatehouse in his new twin towered work, adding a chapel, and altering

the east range. Even though this range was regarded as ‘a

new work' in 1516, it was virtually rebuilt in the latter part of the

reign of James V (1513-42). This James first reworked the east

range around 1536-37, inserting buttresses to the west, and both

blocking and recutting the doors and windows to make a more regular

facade. He also added dormer windows. The long gallery was

converted into apartments and the range extended eastwards to add a

replacement gallery overlooking the gardens below. One buttress

of this work carries the date 1536. He then had the south range

altered by adding a stone gallery to its north side and reworked the

south elevation parapet before 1539 and finally heightened the

gatehouse by 1541. The courtyard facades are thought to have been

the design of 2 French master masons, Nicholas Roy and Moses

Martin. Their buttresses modelled as classical columns and

incorporating medallion busts contrast sharply with the work of the

Scottish mason who had previously worked at Holyrood House, Edinburgh.

Sadly the restoration work of the 1890s stripped most of the site of

their archaeological layers, clearing down to the bedrock on which the

foundations are built. Despite this, it is clear that the palace

originated in the fifteenth and not the sixteenth century.

One interesting thought is that as the original castle quite possibly

lay under the current palace, the irregular stonework of the rear of

the original rectangular gatetower might just belong to this, rather

than the later palace.

Why not join me

at Falkland and other

Great Scottish Castles this Spring?

Information on tours at Scholarly

Sojourns.

Copyright©2022

Paul Martin Remfry

Attached

to the fragment of the

foundations of the east curtain were the slight remains of a half round

drum tower at the north-east end of the enceinte. This was about

25' in diameter and contained a central well shaft. The 1990s

excavation thought that this structure had been 'dismantled and

entirely

restored' by Lord Bute during his excavations in the 1890s. Even

worse, a well head, perhaps of seventeenth or eighteenth century

design, had been introduced into the tower site. Quite clearly

Bute's desire to find the site of Rothesay's incarceration had led to

this rebuilding and insertion. The attached photograph shows the

possible original tower foundations under the Victorian folly of 3

courses of sloping plinth. The faked well head is also visible.

Attached

to the fragment of the

foundations of the east curtain were the slight remains of a half round

drum tower at the north-east end of the enceinte. This was about

25' in diameter and contained a central well shaft. The 1990s

excavation thought that this structure had been 'dismantled and

entirely

restored' by Lord Bute during his excavations in the 1890s. Even

worse, a well head, perhaps of seventeenth or eighteenth century

design, had been introduced into the tower site. Quite clearly

Bute's desire to find the site of Rothesay's incarceration had led to

this rebuilding and insertion. The attached photograph shows the

possible original tower foundations under the Victorian folly of 3

courses of sloping plinth. The faked well head is also visible.