Dunstaffnage Castle

The castle lies 3 miles north-north-east of Oban, situated on a

platform of

conglomerate rock on a promontory at the south-west side of the

entrance to

Loch Etive and is surrounded on 3 sides by the sea. The

strategic location guards the entrance to the nearby loch and the

strategic pass of Brander. The prefix dun in the name means

"fort" in Gaelic, while the rest of the name is thought to derive from

the Norse stafr-nis for "headland of the staff". Such a mix of

languages seems unlikely and the medieval name of the site, Dunstafinch, would more like have the normal inch ending for island, thus giving the Fort of Staf Island. The castle is

said to date back to the thirteenth century and is associated

wrongly with the oceanside castle of Sween 30 miles to the south,

but

correctly with Tioram, 30 miles to the north. It should also be

associated with Dunvegan (miles away on Skye), Kisimul (90 miles away on Barra) and Mingarry (30 miles

north-west) all of these castles being western seaboard castles set on

rocky

outcrops. Dunstaffnage was probably built by the MacDougall lords

of Lorn, descendants of Somerled (d.1164). It would seem likely

that the other castles (except for Sween) also were.

History

The castle is claimed to have been built by Lord Duncan MacDougall of

Lorn and grandson of Somerled (d.1164). The ‘evidence' for

this is that - to quote Historic Scotland - ‘the architecture of

Dunstaffnage castle strongly suggests that it was begun by this Duncan

around 1220'. In reality the castle is first mentioned in 1297 as

one of the 3 castles of Alexander MacDougall, the grandson of

Duncan. It was obviously a viable fortress at this time.

The idea that any of the castle masonry can be that easily dated is,

well, dated! The history of the castle could date back to the

ninth century when there was a Pictish fort called Dun Monaidh which

has been

suggested was Dunstaffnage. However, no trace of this has been

noted in the excavations that have occurred. It has also been

alleged in later Norwegian sagas that King Magnus Barefoot was granted

all the islands of Western Scotland by King Edgar in 1098.

Whether true or not, the west seaboard of Scotland continued to be

nominally controlled by Scottish kings after this date. In 1138,

during the battle of the Standard, the men of the Isles and Lorne

(Argyll) formed part of the Scottish host. However by 1150, and

possibly a decade earlier, Somerled had come to the fore in the Western

Isles and aligned himself as an independent ruler, with family members

opposed to the rule of King Malcolm IV (1153-65). Somerled

finally fell in battle or by treachery at Renfrew on the Clyde in

1164. His descendants then ruled Lorne, of which Dunstaffnage

seems to have been the principal fortress and, judging by the remains,

the curtain wall of the castle could date back to this time.

Indeed the masonry style of Saddell abbey, allegedly founded by Somerled

(Sconedale) in 1160, is quite similar to the masonry style of the

towers and curtain at Dunstaffnage. Obviously attempting to date

such structures accurately is a difficult task, but current academic

opinion is that the church ruins date from the twelfth century.

If this is so, then there is no reason why the castle might not be that

old too. Further we are led to believe from chronicle references

that King Magnus Barefoot (d.1103) also built castles.

In Lorne Somerled was succeeded by Dougal (bef.1151-92+) from whom the

MacDougals are descended. Dougal's son, Duncan

(bef.1195-1244/48), is the man credited with building Dunstaffnage

castle by hearsay. We know little of his career. He was

unsuccessfully attacked by his Norwegian-backed brother, Uspak, who was

afterwards killed in an attack on Rothesay castle after he had

travelled to Rome in 1237. Duncan was still alive and was a joint

signatory of a royal letter of King Alexander II sent to the pope in 1244

as Dunkan de Ergatile

(Argyll). In 1248 Duncan's son, Ewen MacDougall (bef.1225-68+),

went to Norway and was confirmed as king of the Isles by King Hakon

after the death of King Harold of Man (1249). This made Ewen

master of an area almost as large as that his great-grandfather,

Somerled, had controlled. At this point King Alexander II

demanded that Ewen surrender to him his 4 great castles (Dunstaffnage,

Tioram, Kisimul, Cairnburgh? Dunaverty? Aros?) in return for ‘a

much larger dominion in Scotland and along with it our

friendship'. Ewen rejected the demand, saying he could serve 2

masters - Alexander and Hakon - provided that they were not

enemies. In reply Alexander invaded Argyll and reached Oban bay

and there contracted a fever, dying on Kerrera island, opposite Oban,

on 8 July 1249. His intention on this campaign may have been to found Tarbert castle and take Dunstaffnage.

When his son, King Alexander III, reached 14 years of age that September, King Henry III notified his backing for Eugenius de Argoythel,

stating that he if should incur forfeiture, the king, as principal

advisor for King Alexander, would see it amended. Following King

Alexander III's repulse of the Norse influence in Argyll in 1263-66,

the MacDougalls backed him. Ewen is last heard of in 1268.

His son, Alexander, was made the first sheriff of Argyll in 1293 when

he was a supporter of King John Balliol (1292-96) and then King Edward

I. Alexander remained loyal to Edward as the murdered Comyn was a

relative of his. Consequently he defeated the newly crowned

Robert Bruce at the battle of Dalrigh, between Loch Lomond and

Dunstaffnage. For this fight the unreliable Barbour is the only

authority.

According to the more reliable Fordun, two years later, King Robert

Bruce (1306-29) defeated Alexander of Argyll (d.1310) at the battle of the

Brander Pass at some time between 15 and 23 August 1308. This

brought Alexander to Bruce's St Andrew's parliament of 16 March

1309. There he seems to have refused to pay Bruce homage and

retired to the west, where, with his son, John, (d.1316), he kept up the

fight from his main centre at Dunstaffnage (Dunstafinch)

castle. On 11 March 1309, John of Argyll, on his sickbed, had received a letter from Edward II

and replied stating that Bruce himself had approached his lands with

between 10,000 and 15,000 men by both land and sea. Lorne had

only 800 men to oppose

him and 500 of these were being paid to keep his borders secure, while

the barons of Argyll had sent him no help. Despite this Bruce had

asked for a truce for a short while, which Lorne had granted him.

Further, despite him being ill for six months it was untrue, as Bruce

boasted, that he had asked to come to his peace. Further he was

ready to march against Bruce when the king came with his army. He

finished by stating that he had 3 castles (Dunstaffnage, Inverlochy

& Coeffin?) and a lake 24 miles long to defend on which he had

properly manned ships. However, he was not sure of the attitude of

his neighbours. Subsequently Dunstaffnage castle was besieged by

Bruce's supporters and fell before 16 June 1309, by which date both

John and his father were sheltering in England - never to return.

Thus began Dunstaffnage's career as a royal castle, controlled by a

series of keepers. In reply the MacDougalls probably built

Dunollie castle later in the century, near to their previous fortress

of Dunstaffnage which was now out of their hands. Dunstaffnage

castle seems to have remained a neglected royal stronghold from this

point onwards for several years, although there is no evidence that it

was slighted like many other royal castles. Indeed Arthur

Campbell was appointed keeper by Bruce in 1321, the first of many

Campbells to be involved with the castle.

The MacDonald lords of the Isles seem, in the anarchy following King

Robert's death, to have acquired control of Dunstaffnage and

Lorn. When John of Lorne's grandson, another John, returned to

Scotland he began to reclaim his lands with the help of both King David II

and King Edward Balliol. Finally, in 1358, King David II granted

to John, known as Gallda - the English speaker or lowlander - all of

the lands previously held by his grandfather. Thus he regained

Dunstaffnage castle. John died between 1371 and 1377, without a

legitimate son. His illegitimate son managed to hold on to

Dunollie castle and the lands about it, but Dunstaffnage castle passed

with the lordship of Lorne to John's son-in-law, John Stewart of

Innermeath (d.1421).

The MacDonald lords of the Isles seem, in the anarchy following King

Robert's death, to have acquired control of Dunstaffnage and

Lorn. When John of Lorne's grandson, another John, returned to

Scotland he began to reclaim his lands with the help of both King David II

and King Edward Balliol. Finally, in 1358, King David II granted

to John, known as Gallda - the English speaker or lowlander - all of

the lands previously held by his grandfather. Thus he regained

Dunstaffnage castle. John died between 1371 and 1377, without a

legitimate son. His illegitimate son managed to hold on to

Dunollie castle and the lands about it, but Dunstaffnage castle passed

with the lordship of Lorne to John's son-in-law, John Stewart of

Innermeath (d.1421).

King James I seized the castle from the rebel Stewarts in 1431, following the defeat of the earl of Mar at the battle of Inverlochy.

The king is subsequently said to have proceeded to execute 300

Highlanders found within the castle. The castle seems to have

remained in royal hands from this date. In 1455 James Douglas,

ninth earl of Douglas, stayed at Dunstaffnage on his way to treat with

Lord John MacDonald of the Isles. This followed James II's attack

on Douglas power, and led to the signing of the treaty of

Westminster-Ardtornish whereby Douglas and the MacDonalds agreed to

divided Scotland between themselves with English support. A later

keeper of Dunstaffnage, John Stewart of Lorn, was a rival of Alan

MacDougall - a descendant of Somerled - and was stabbed by Alan's

supporters on his way to his marriage at Dunstaffnage chapel in 1463,

although he survived long enough to make his vows. MacDougall

then took the castle, but was ousted by James III, who in 1470 granted

Dunstaffnage to Colin Campbell, first earl of Argyll.

The earls of Argyll appointed captains to oversee the running of

Dunstaffnage castle. Changes were made to the buildings,

particularly the gatehouse, which is said to have been rebuilt around

this time. The Campbells remained loyal subjects of the Crown and

Dunstaffnage was used as a base for government expeditions against the

MacDonald lords of the Isles during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In 1502

Captain Alexander Campbell of Dunstaffnage was required to keep the

castle in repair with a peacetime garrison of 6 armoured men, a

watchman and a porter. James IV visited Dunstaffnage on two

occasions and expeditions against the MacDonalds were launched from

here in 1493, 1540, 1554 and 1625.

During the First English Civil War Dunstaffnage held

out against Montrose's army in 1644 and later hanged his second in

command, Alexander MacDonald, from the battlements before burying him

outside the nearby chapel. Following the failure of the rising of

the 9th earl of Argyll against the Catholic James VII in 1685, the earl

was executed and Dunstaffnage castle, which he had used as his base,

was burned by royalist troops. The castle was occupied by

government troops during the Jacobite risings of 1715 and 1745,

while Flora MacDonald, who helped Bonnie Prince Charlie escape to

Skye, was briefly imprisoned here while en route to London.

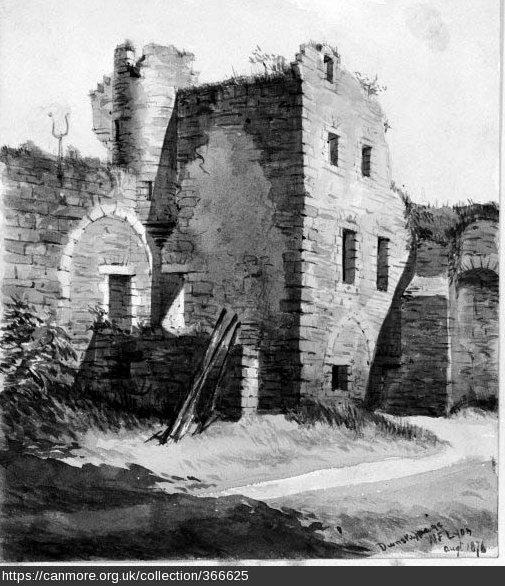

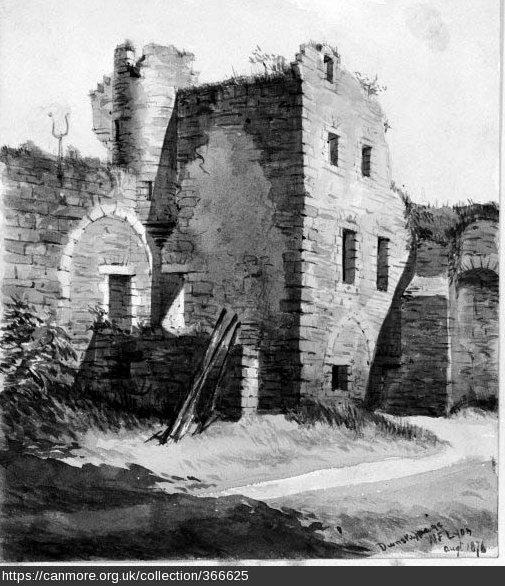

The Campbells continued to add to the castle, building a new house over

the old west range in 1725. However, the rest of the castle was

left to decay and by 1767 only the new house may have been habitable

together with ‘the old tower'. In 1810 an accidental fire

gutted the castle and the captains ceased to live there, moving to

Dunstaffnage house until this too burned down in 1940. Despite

the fire, various tenants lived in the 1725 house within the castle

until 1888. In a final irony, the roof of the new house collapsed

during the Great War of 1914-18 before the captain, who was a prisoner

of war, could return and restore it.

Description

Description

Dunstaffnage is an irregular quadrangular enclosure castle with rounded

angles. The whole measures some 115' by 98', and has a

circumference of about 390'. The wall tops stand up to 60' above

the surrounding ground level, although some of this height includes the

west to east sloping bedrock the castle stands upon. The walls are up

to 11'

thick and were topped by a later parapet which is now mostly

gone. The tower to the north and the quite different turrets to

the west

are of a later build than the bulk of the curtain walls. This can

be seen by their different manner of construction, with the walls

containing many light coloured sneker stones which are absent at the

angle tower and turrets. Further, a recent excavation found the

foundations of the original wall cutting through the middle of the

basement of the north tower. The crossbow loops that pierce the

walls

and towers are also dressed in the lighter sandstone. Many of

these have been blocked and some converted into gunports.

The north tower is the largest of the enceinte (about 30' diameter) and

consisted of at least 3 storeys. Access to the upper level

may have only been gained via the wallwalk. This suggests a

strong sense of a need for defence for the occupant of the presumably

living quarters higher up in the tower. The batter at the base of

the keep is built from smaller stones than the rest of the castle and

therefore may have been a late addition to stabilise the tower, or even

a remnant of an earlier structure. The homogenous bulk of the

outer facing has certainly been replaced as there is now no trace of

any openings, of which there are some vestiges internally.

Excavation has proved that there were originally 3 loops in embrasures

similar to those still seen in the west tower on the ground floor.

These have later been totally infilled.

The basement level is now entered from the east range, but this doorway

looks much later. The tower has been heavily altered internally

and chimney flues from the adjoining east and west ranges have been added

into its thickness. There is also a garderobe with a large

corbelled out chute set in the junction with the north curtain. This

was entered from the spiral stair which allowed access up and down the north tower. The external join between curtain and the added north tower

is obvious here. The north curtain beyond contains one much damaged

deeply set loop with a rounded arch next to a fireplace as well as a

smaller projecting garderobe. This shows that an earlier building

stood here before being transformed, probably in the fifteenth century,

into a kitchen. This in turn was replaced by the ‘new

house' in 1725. When this was abandoned the dormer windows were

transferred to the gable of the gatehouse.

The west turret (20' diameter) is set well back into the enceinte in a

similar manner to the north side of the north tower. It was also

obviously residential, having a fireplace on the raised ground floor as

well as a garderobe in the north curtain and two loops set in large

embrasures. Beneath this floor was a prison with attached

garderobe, but no light. Entrance was gained via a short flight

of external stairs. From here a doorway led into the raised

ground floor. Set in the east wall of the doorway was a curving

mural stair that led to the upper floors (see Inverlochy

on these). Three embrasures, reached via an offset from the steps

up to the west turret, pierce the west wall, though the south one has been

partially converted into a stairway to the wallwalk. These

embrasures and those of the S&E walls are different to the solitary

loop in the north curtain.

The south turret is little more than a bulge in the curtain angle, but it

contained a small rectangular chamber with a single south-west facing

loop. The south curtain contained two further embrasures with loops,

before the irregular gatehouse is reached at the south-east angle of the

castle. This seems to have originally consisted of another round

turret, of which only the south-west face remains. This was pierced by a

projecting rectangular gatehouse in the fifteenth century

which has been much modified in later centuries and still contains the

captain's house. This takes the form of a 4 storey harled

towerhouse, with the entrance passage, some 20' above external ground

level, running through half the vaulted basement, the other half

forming guard rooms with loops facing the gate. The present

approach to the gate is by a stone stair, replacing an earlier

drawbridge. The tower was remodelled in the eighteenth century to

provide reception rooms and a private suite. Buried in the south wall

of the gatehouse can be seen the one remaining wall of a round tower

that was probably about 25' in diameter. As there is a fissure in

the rock immediately north of the tower, where the gate now is, it is

logical that this was the original entrance to the site. In the

rear wall of the gatehouse the jambs of the interior gateway have been

picked out in the harling. This shows a large gate with pointed

arch in a form that could have been used at any time from 1200 to

1400. The somewhat similar, but less regular and partially

blocked, outer gate probably dates to the sixteenth century and the Romanesque arch within to the seventeenth or eighteenth century.

The south turret is little more than a bulge in the curtain angle, but it

contained a small rectangular chamber with a single south-west facing

loop. The south curtain contained two further embrasures with loops,

before the irregular gatehouse is reached at the south-east angle of the

castle. This seems to have originally consisted of another round

turret, of which only the south-west face remains. This was pierced by a

projecting rectangular gatehouse in the fifteenth century

which has been much modified in later centuries and still contains the

captain's house. This takes the form of a 4 storey harled

towerhouse, with the entrance passage, some 20' above external ground

level, running through half the vaulted basement, the other half

forming guard rooms with loops facing the gate. The present

approach to the gate is by a stone stair, replacing an earlier

drawbridge. The tower was remodelled in the eighteenth century to

provide reception rooms and a private suite. Buried in the south wall

of the gatehouse can be seen the one remaining wall of a round tower

that was probably about 25' in diameter. As there is a fissure in

the rock immediately north of the tower, where the gate now is, it is

logical that this was the original entrance to the site. In the

rear wall of the gatehouse the jambs of the interior gateway have been

picked out in the harling. This shows a large gate with pointed

arch in a form that could have been used at any time from 1200 to

1400. The somewhat similar, but less regular and partially

blocked, outer gate probably dates to the sixteenth century and the Romanesque arch within to the seventeenth or eighteenth century.

Two embrasures with decorated twin lancet windows are blocked, one

fully and one partially, within the curtain of the highly ruined fifteenth century east range. These windows are similar to the ones in the ‘13th century'

chapel outside the castle. Originally this would have been the

great hall of the fortress, set above vaulted store chambers.

There is a large rectangular well roughly centrally in the ward.

A ruined ‘13th century'

chapel lies around 500' to the south-west of the castle. This has

been

claimed to have been built by Duncan MacDougall of Lorn (d.1244+).

However, the 4 pillared corners of the structure bear a greater

resemblance to the keep at Peak than anywhere else and this appears to

date to the reign of King Henry II (1154-89). Internally

the chapel has fine Romanesque windows of outstanding

quality.

The chapel is 66' by 20', while the lancet windows have dog-tooth

carving and fine wide-splayed arches internally. The church was

ruinous by 1740 when a burial aisle was built on to the east end to

serve as a resting place for the captains of Dunstaffnage and their

families.

Why not join me at Dunstaffnage and other Great Scottish Castles this Spring? Information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2016

Paul Martin Remfry

Description

Description

The MacDonald lords of the Isles seem, in the anarchy following King

Robert's death, to have acquired control of Dunstaffnage and

Lorn. When John of Lorne's grandson, another John, returned to

Scotland he began to reclaim his lands with the help of both King David II

and King Edward Balliol. Finally, in 1358, King David II granted

to John, known as Gallda - the English speaker or lowlander - all of

the lands previously held by his grandfather. Thus he regained

Dunstaffnage castle. John died between 1371 and 1377, without a

legitimate son. His illegitimate son managed to hold on to

Dunollie castle and the lands about it, but Dunstaffnage castle passed

with the lordship of Lorne to John's son-in-law, John Stewart of

Innermeath (d.1421).

The MacDonald lords of the Isles seem, in the anarchy following King

Robert's death, to have acquired control of Dunstaffnage and

Lorn. When John of Lorne's grandson, another John, returned to

Scotland he began to reclaim his lands with the help of both King David II

and King Edward Balliol. Finally, in 1358, King David II granted

to John, known as Gallda - the English speaker or lowlander - all of

the lands previously held by his grandfather. Thus he regained

Dunstaffnage castle. John died between 1371 and 1377, without a

legitimate son. His illegitimate son managed to hold on to

Dunollie castle and the lands about it, but Dunstaffnage castle passed

with the lordship of Lorne to John's son-in-law, John Stewart of

Innermeath (d.1421). Description

Description The south turret is little more than a bulge in the curtain angle, but it

contained a small rectangular chamber with a single south-west facing

loop. The south curtain contained two further embrasures with loops,

before the irregular gatehouse is reached at the south-east angle of the

castle. This seems to have originally consisted of another round

turret, of which only the south-west face remains. This was pierced by a

projecting rectangular gatehouse in the fifteenth century

which has been much modified in later centuries and still contains the

captain's house. This takes the form of a 4 storey harled

towerhouse, with the entrance passage, some 20' above external ground

level, running through half the vaulted basement, the other half

forming guard rooms with loops facing the gate. The present

approach to the gate is by a stone stair, replacing an earlier

drawbridge. The tower was remodelled in the eighteenth century to

provide reception rooms and a private suite. Buried in the south wall

of the gatehouse can be seen the one remaining wall of a round tower

that was probably about 25' in diameter. As there is a fissure in

the rock immediately north of the tower, where the gate now is, it is

logical that this was the original entrance to the site. In the

rear wall of the gatehouse the jambs of the interior gateway have been

picked out in the harling. This shows a large gate with pointed

arch in a form that could have been used at any time from 1200 to

1400. The somewhat similar, but less regular and partially

blocked, outer gate probably dates to the sixteenth century and the Romanesque arch within to the seventeenth or eighteenth century.

The south turret is little more than a bulge in the curtain angle, but it

contained a small rectangular chamber with a single south-west facing

loop. The south curtain contained two further embrasures with loops,

before the irregular gatehouse is reached at the south-east angle of the

castle. This seems to have originally consisted of another round

turret, of which only the south-west face remains. This was pierced by a

projecting rectangular gatehouse in the fifteenth century

which has been much modified in later centuries and still contains the

captain's house. This takes the form of a 4 storey harled

towerhouse, with the entrance passage, some 20' above external ground

level, running through half the vaulted basement, the other half

forming guard rooms with loops facing the gate. The present

approach to the gate is by a stone stair, replacing an earlier

drawbridge. The tower was remodelled in the eighteenth century to

provide reception rooms and a private suite. Buried in the south wall

of the gatehouse can be seen the one remaining wall of a round tower

that was probably about 25' in diameter. As there is a fissure in

the rock immediately north of the tower, where the gate now is, it is

logical that this was the original entrance to the site. In the

rear wall of the gatehouse the jambs of the interior gateway have been

picked out in the harling. This shows a large gate with pointed

arch in a form that could have been used at any time from 1200 to

1400. The somewhat similar, but less regular and partially

blocked, outer gate probably dates to the sixteenth century and the Romanesque arch within to the seventeenth or eighteenth century.