Duffus Castle

History

Moray was in the Celtic heartlands of Scotland which is traditionally

seen as hostile to the kings of the Scots and their Anglo-Norman

leaning ways. At the beginning of the twelfth century Moray was ruled by

the mormaer, Angus. He was a grandson of King Lulach of Scotland

(d.1058), the stepson of King Macbeth (1040-57). Angus rebelled

against King David I in 1130, who, after quashing the revolt, began to

populate the district with foreign nobles answerable directly to him

and not to the mormaer.

One of these new arrivals was Freskin, the forefather of the Moray or

Murrey clan. He received the land of Duffus directly from King

David and although his origins are completely unknown, it is generally

stated that he was of Flemish extraction. It would seem to have

been Freskin who built the great earthwork of the castle on boggy

ground in the Laich of Moray. Duffus castle and its chapel were

definitely standing by 1222. This can be adduced as Bishop Bryce

of Moravia (1203-22) made a charter concerning the founding of the

chapel of Duffus castle. This charter confirmed that Hugh Moravia

of Duffus had founded a free chapel in Duffus castle and endowed a

chaplain, his son Andrew, there. The grant included all the land

called Aldetoun which was between it and the old church of Kyntra

(Spynie?), whose boundaries were fully described. It has been

stated that this means that the chapel stood away from the castle, but

the charter makes it quite clear that the chapel was within the

fortress. Presumably the sparse remains of the tower with lancet

windows at Duffus church predates the lost chapel of the castle and is

the church of St Peter of Duffus mentioned before 1222. Hugh

Moravia and his wife were both buried there in St Peter's church,

before 1242 according to the charter of their son, Walter

(d.1262). The chapel - as distinct from the church of Duffus -

was again mentioned in a charter of Walter Moravia on 19 September

1240. A supposition to be drawn from this is that it seems

unlikely that there would have been a stone church and no stone castle

and chapel at Duffus at this time.

Freskin's direct line at Duffus ended in 1269 with the death of Freskin

Moray and the castle, with his daughter, Mary, passed to Reginald

Cheyne (d.1312) in marriage. There is still little evidence of

the form of the castle when the Moray family ceased to hold it.

There is likewise no evidence as to what the Cheyne family did

there. The claim that the castle was attacked by anti-Edwardian

forces in 1297 is most likely untrue. The argument goes that

Duffus must have been attacked before 25 July 1297 because that is the

date when the bishop of Aberdeen, Earl John Comyn of Buchan and

Gartnait of Mar wrote to their king, Edward I, that Andrew Moray and a

horde of felons had hidden themselves in the bogs and woods of the

north. It is beyond comprehension how Wikipedia [thankfully now removed] could fabricate

from this statement, which indeed they quote, that:

It is known that the original

castle was burned down by Andrew Moray in the summer 1297 who descended

on it with what was described as in a letter to King Edward I of

England as 'a very large body of rogues', because it held a garrison of

King Edward's English troops and this had been the impetus for building

a more secure castle of stone.

Obviously the original letter to King Edward states nothing of English

garrisons, Duffus castle, building works there or the actions of Andrew

Moray, other than he and some numerous men with him were against King

Edwards' peace. These men were not rogues, but felons, a type of

criminal who had committed a great crime. As the text of the

original is freely available on the internet, such deliberate

falsehoods as these should be rapidly swept away. Unfortunately

with the misinformation so readily available on Wikipedia it possibly

never will be. The sheer ludicrousness of Wikipedia's

interpretation is shown by a resume of what we really know.

The fact of the matter is that it would appear that Reginald Cheyne

joined the Scottish baronial rebellion in the summer of 1297, for he

was certainly one of those who helped entice William Fitz Warin of Urquhart castle

into an ambush that spring. This firmly places Cheyne with the

rebels and not the Edwardian loyalists like Gartnait, John Comyn, Fitz

Warin and the countess of Mar. Certainly by 20 February 1299,

Cheyne had been captured by royalist forces, as on that day the king

allowed for him to be exchanged for John Kalentir, an Edwardian

royalist. In short, there is no reason for Moray to attack the

lands of his obvious ally in 1297 or at any other time. After

February 1299, if not slightly earlier, Reginald made his peace with

King Edward, for his estates lay within the power of the Comyns of

Buchan who were only overwhelmed and killed by the power of Robert

Bruce after the death of King Edward I in 1307. As such it seems

most unlikely that the rebel Moray, aided by Cheyne, would have burned

his own rebel castle for the rebel cause in 1297! Likewise there

is no evidence that the castle was either attacked or burned for the

Edwardian cause in the same period.

What can be shown is that Reginald Cheyne obviously remained in the

king's peace after 1299 and in 1305 asked for and received from King

Edward I, a grant of 200 oaks from the royal forests of Longmorn and

Darnaway ‘to build his manor of Dufhous'. The previous year

the king had consented for Canon John Spauyding of Elgin having 20 oaks

from the forest of Longmorn (Laund Morgund)

to build his church of Duffus, of which he was the canon. This

suggests, but by no means proves, that major rebuilding was taking

place at this time. Although major building work could occur

after a fire, it is also just as likely to occur when the old wood was

rotten, or even simply when new buildings were being built - or even

when a park was being made around the castle, which might not have been

altered in any way, means or form. Without further evidence we

simply do not know.

There is not much else to say about the history of the castle.

Reginald and Mary's male children were all dead by 1345 and the castle

passed to his daughter who was married to Nicholas Moray, the second

son of the fourth earl of Sutherland, another descendant of Freskin.

The fortress then remained in that family until 1705 when it was

abandoned. In 1689, John Graham, first Viscount of Dundee, was a

guest of Lord Duffus just before the battle of Killiecrankie. As

such he would seem to have been the last important visitor before the

castle's final abandonment.

Description

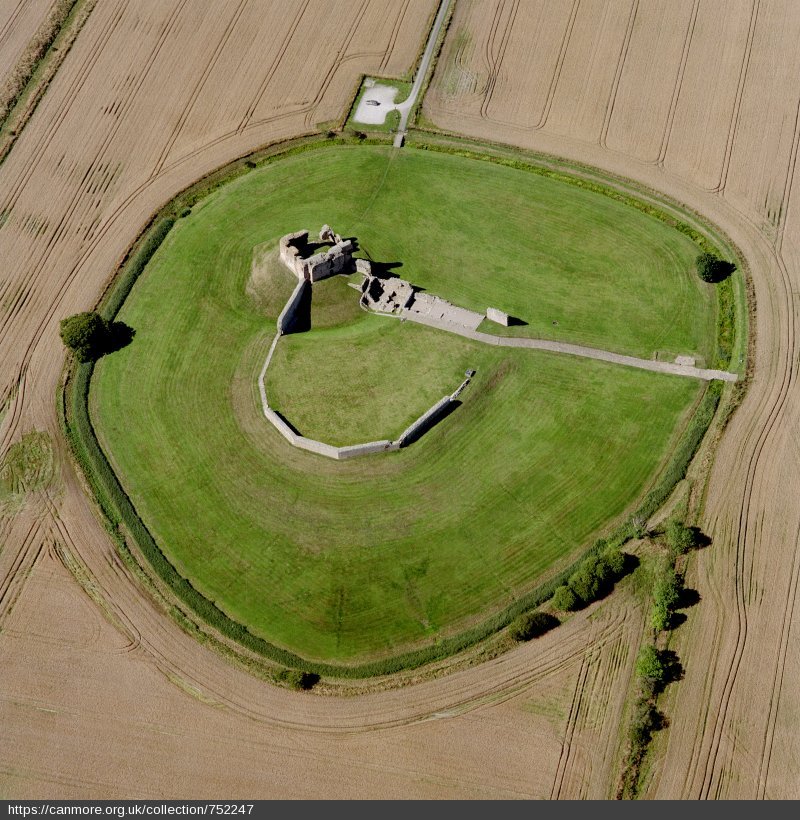

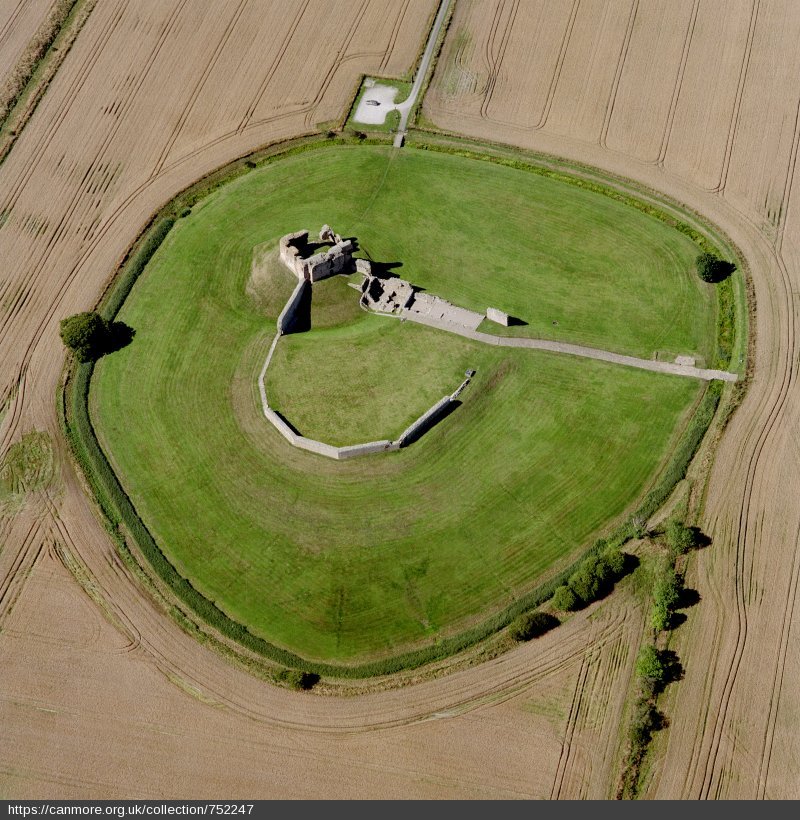

The castle is based on what is known as a motte and bailey structure,

built upon a low natural north to south running ridge. Perched on this is

an ellipsoid circular ditch with a diameter of between 700 and

800'. Presumably the medieval town of Duffus has always stood

over half a mile to the north-west, clustered around the church of St Peter,

while this still water-filled moat of the ‘outer bailey' enclosed

the later orchard around the castle as has been postulated by the

castle excavators. A central polygonal bailey stands within the

large earthwork. This inner ward is about 200' in diameter, with

a motte, some 40' high externally, towards the west end. Excavation

has shown that there was a ditch between the motte and the

bailey. Another ditch follows around the base of the motte

externally and continues around the bailey. The main entrances to

both earthworks seem to have been towards the north-east.

It has always been stated that Duffus castle began its life as a wooden

fortress. There is no archaeological substantiation for this

claim, although excavation in 1983-85 postulated a long occupation

before the site was deliberately covered in half an inch of clay

burying late twelfth to early thirteenth century pottery. It was therefore

thought, but by no means proved, that this must mark the commencement

of the first masonry on the site in the fourteenth century. The castle ruins have been generally dated as fourteenth to sixteenth century

on the grounds that this was what such masonry should look like.

From these non-scientific guestimates, it was deduced that the known

wooden building operations of 1305 were the time when the wooden castle

was converted into stone, as 200 oaks would not have been sufficient to

fortify the entire site in wood. Such implications are illusory

as there is no evidence that Cheyne did not acquire further oaks from

elsewhere - 200 oaks were merely the royal contribution to the

project. However, if the oaks were for timber work within the

fortress, there is no reason at all to suspect that this entailed the

building of the masonry. After all the original castle timber

work within the masonry defences might have been burned before 1305,

which would have necessitated in the castle's woodwork being replaced,

not a new stone castle being built. In consequence we are left

with no solid dating evidence for the castle, other than educated

guesswork and the categorical statement that the archaeologists found

no evidence of burning, nor of a wooden fortress. As such the

archaeology would state that the current masonry castle could not have

been founded before the clay layer was laid down over early thirteenth century

pottery and that no destruction debris was found on site. As such

it seems reasonable to state that the masonry castle of keep and bailey

was built in the period immediately after ‘the early thirteenth century' (whenever that might be!) and not in the early fourteenth century as guesswork has previously stated. If this were not true then mid or late thirteenth century

pottery would be expected in the soil beneath the clay laid immediately

before the masonry was built. This suggests that wooden motte and

bailey castle was built in the twelfth century

and then dismantled and a new stone castle was built over the site

before 1275 at the very latest, and possibly as early as the first

decades of the thirteenth century.

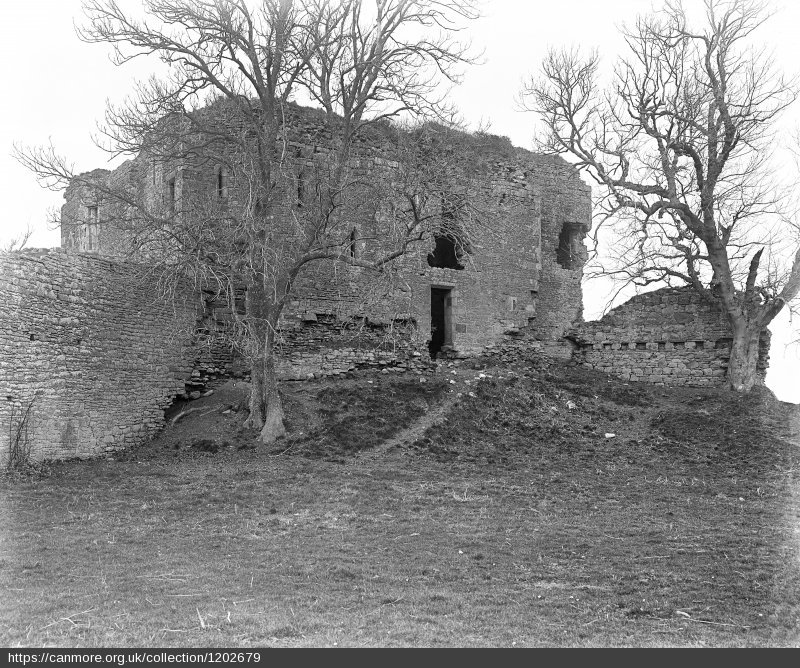

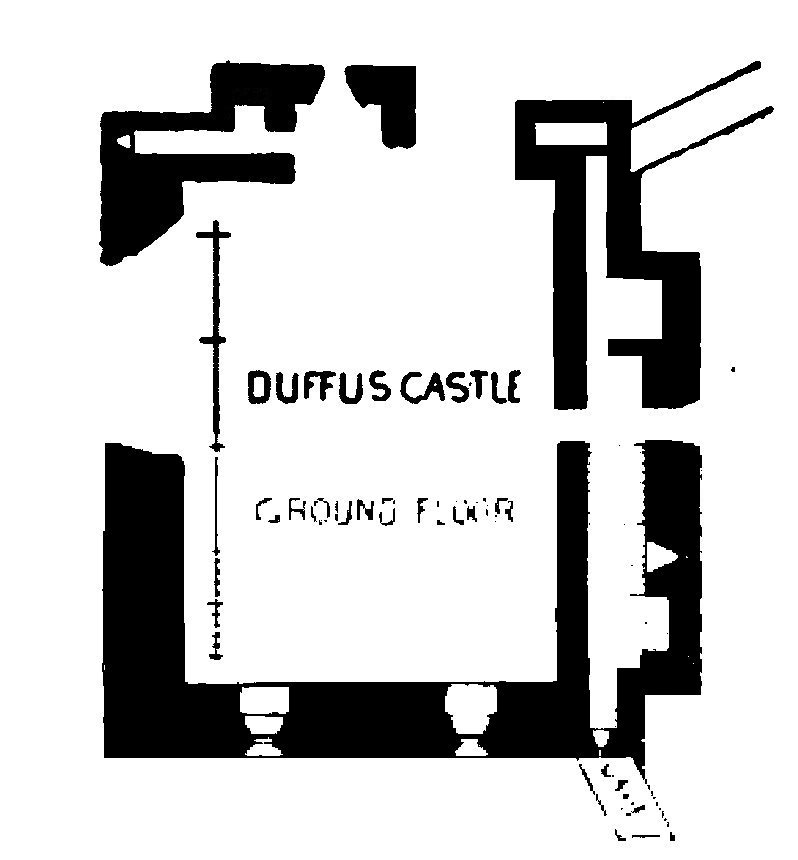

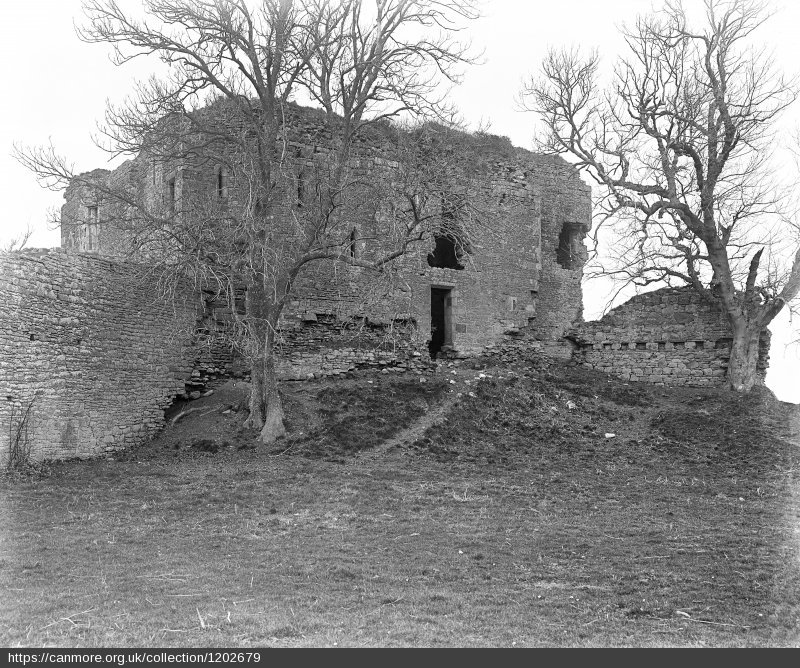

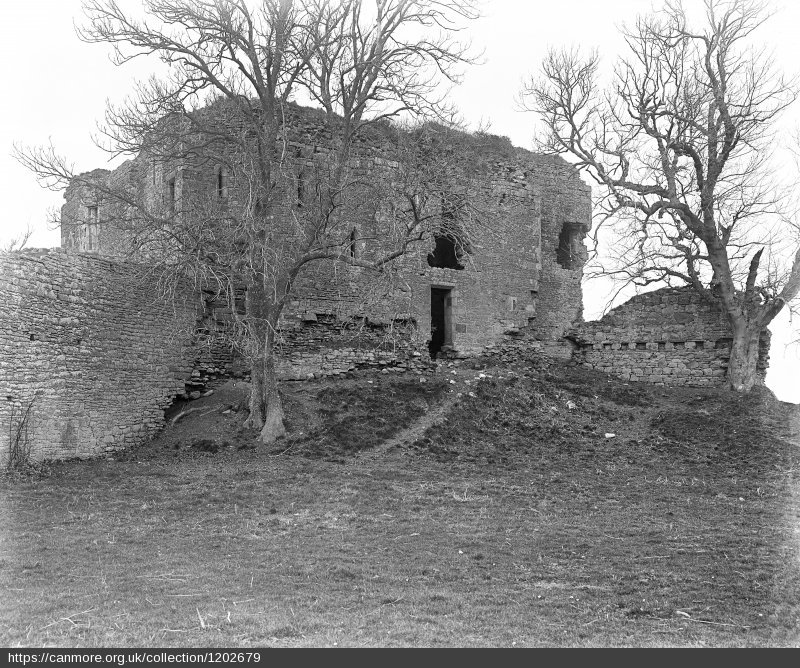

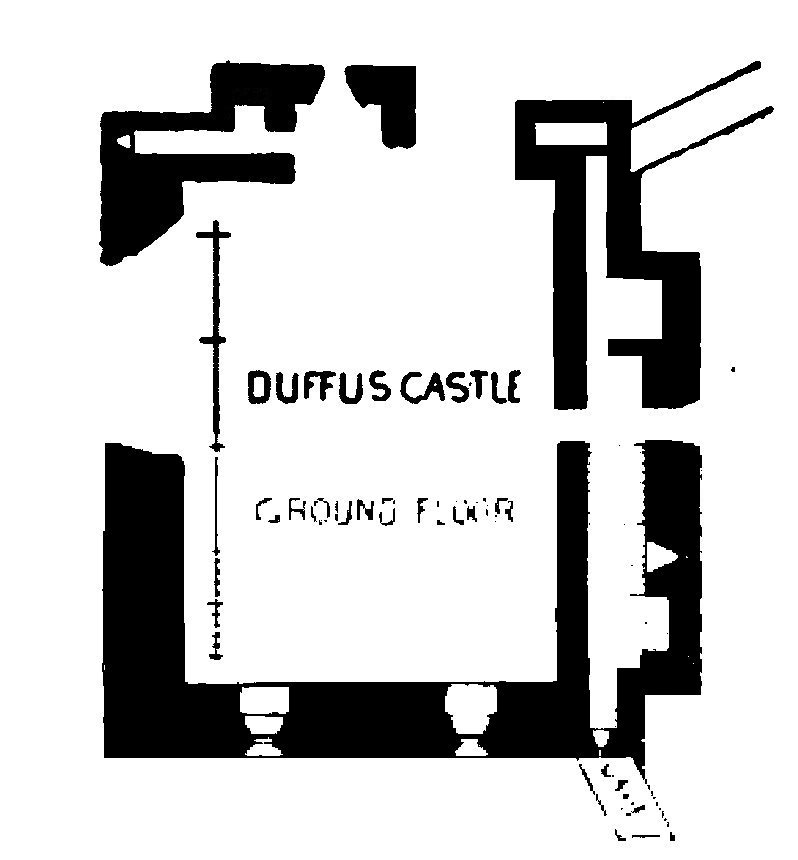

The heart of the masonry castle was the unique two storey rectangular

tower built on the motte. The tower is about 60' by 50' and has

thickenings in its walls to accommodate mural chambers and is set on a

powerful batter which is topped by two sloping courses of

masonry. The loops and windows above are mainly rectangular in

shape - a form which is seen from the twelfth to the sexteenth century

in Britain. However it has been noted that the smaller windows in

the tower are similar to those found at Elgin cathedral which was

founded in stone in 1224. It is therefore possible that the keep

at Duffus was built around the same time, approximately a hundred years

after it has been suggested the castle was first founded and some 80

years before guesswork suggested that it might have been built in

stone, ie a very broad around 1225.

The heart of the masonry castle was the unique two storey rectangular

tower built on the motte. The tower is about 60' by 50' and has

thickenings in its walls to accommodate mural chambers and is set on a

powerful batter which is topped by two sloping courses of

masonry. The loops and windows above are mainly rectangular in

shape - a form which is seen from the twelfth to the sexteenth century

in Britain. However it has been noted that the smaller windows in

the tower are similar to those found at Elgin cathedral which was

founded in stone in 1224. It is therefore possible that the keep

at Duffus was built around the same time, approximately a hundred years

after it has been suggested the castle was first founded and some 80

years before guesswork suggested that it might have been built in

stone, ie a very broad around 1225.

Unlike many towers, the entrance at Duffus was on the ground floor via

a currently flat-headed doorway which could well be an insertion or

modification. Despite the limited space offered by the structure,

the ground floor seems to have been merely storage space. The

ashlar masonry around the interior of the door certainly shows that

this has been replaced at some point. Within the doorway mural

passageways led left and right, the one to the south also housed the steps

up to the next floor. The first floor held the lord's hall, a

latrine and bed chambers.

From first floor level 2 rectangular doorways exited onto the walkway

of the curtain wall, showing that either the wallwalks and therefore

the curtains were already standing when the tower was built or that the

two were built simultaneously. Further the masonry of the bailey

wall, although well laid, is inferior to that of the keep and the

masonry style of the north wall is different to that of the rest of the

enceinte. Quite possibly the south-east polygonal section of the curtain

wall, where no modern archaeological surveys have been undertaken, is

older than the keep. The positioning of the keep doorways show

that even the highest standing stretches of bailey wall seem to have

lost a third of their height before taking the battlements into

consideration. The bailey curtain completely enclosed the ward in

approximately ten sweeps of wall, the junctions between each straight

section being protected by some high quality quoining. There was

also a single sloping course of plinthing at the base of the wall which

is best seen where the wall passes over the motte ditch. There

are also 3 surviving postern gates, one to the west and 2 to the east.

The main gatehouse would have been to the north, but has totally

disappeared.

Various post holes built into the curtain wall indicate the presence of

a number of buildings around its circuit. Along the longest

straight section of wall, on the north side of the bailey, a later building

was erected that housed a kitchen, great hall with reception room and a

great chamber bedroom. It is possible that this building was

constructed by the Sutherlands after 1345 and was still in occupation

until the early eighteenth century.

Various post holes built into the curtain wall indicate the presence of

a number of buildings around its circuit. Along the longest

straight section of wall, on the north side of the bailey, a later building

was erected that housed a kitchen, great hall with reception room and a

great chamber bedroom. It is possible that this building was

constructed by the Sutherlands after 1345 and was still in occupation

until the early eighteenth century.

It is not known when the serious subsidence took place, but there is

evidence of repairs being made before the keep partially collapsed down

the motte. The newer hall shows signs of continued alterations

over time, so possibly this building was built when the keep was

abandoned. The collapse of the tower suggests that the motte was

either built of inferior materials that could not carry the weight of

the tower, or that the motte was not allowed to settle before the keep

was built. In the latter case the keep could be almost as old as

the earthworks.

Why not join me at Duffus and other Great Scottish Castles this Spring? Information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2016

Paul Martin Remfry

The heart of the masonry castle was the unique two storey rectangular

tower built on the motte. The tower is about 60' by 50' and has

thickenings in its walls to accommodate mural chambers and is set on a

powerful batter which is topped by two sloping courses of

masonry. The loops and windows above are mainly rectangular in

shape - a form which is seen from the twelfth to the sexteenth century

in Britain. However it has been noted that the smaller windows in

the tower are similar to those found at Elgin cathedral which was

founded in stone in 1224. It is therefore possible that the keep

at Duffus was built around the same time, approximately a hundred years

after it has been suggested the castle was first founded and some 80

years before guesswork suggested that it might have been built in

stone, ie a very broad around 1225.

The heart of the masonry castle was the unique two storey rectangular

tower built on the motte. The tower is about 60' by 50' and has

thickenings in its walls to accommodate mural chambers and is set on a

powerful batter which is topped by two sloping courses of

masonry. The loops and windows above are mainly rectangular in

shape - a form which is seen from the twelfth to the sexteenth century

in Britain. However it has been noted that the smaller windows in

the tower are similar to those found at Elgin cathedral which was

founded in stone in 1224. It is therefore possible that the keep

at Duffus was built around the same time, approximately a hundred years

after it has been suggested the castle was first founded and some 80

years before guesswork suggested that it might have been built in

stone, ie a very broad around 1225. Various post holes built into the curtain wall indicate the presence of

a number of buildings around its circuit. Along the longest

straight section of wall, on the north side of the bailey, a later building

was erected that housed a kitchen, great hall with reception room and a

great chamber bedroom. It is possible that this building was

constructed by the Sutherlands after 1345 and was still in occupation

until the early eighteenth century.

Various post holes built into the curtain wall indicate the presence of

a number of buildings around its circuit. Along the longest

straight section of wall, on the north side of the bailey, a later building

was erected that housed a kitchen, great hall with reception room and a

great chamber bedroom. It is possible that this building was

constructed by the Sutherlands after 1345 and was still in occupation

until the early eighteenth century.