Dirleton

Castle

Like many other Scottish castles, Dirleton castle is said

to owe much of its style to French rather than English

influences. It is therefore little surprise that Dirleton is

often linked with Coucy-le-Chateaux, north of Paris, in

France. This design of a larger keep or donjon and lesser

D-shaped towers set in a curtain wall can also be seen at Bothwell,

Inverlochy and Kildrummy castles. Other examples are Coull and

Tibbers.

History

It is uncertain when Dirleton castle was begun, but the Vaux family,

who are said to have held the site during the reign of King David I

(1124-53), had come north to Scotland from Normandy, via England, in

the service of the Anglo-Scottish kings. Nothing is recorded

of the family early history, but William Vaux was lord of Gullane

during the reign of King William the Lion (1165-1214). In

that time he granted Eyebroughty island, Gullane church and the chapel

of St Andrew in Dirleton to Dryburgh abbey. The grant of

Dirleton chapel suggests that there was a castle there at the time as

castle and chapel were often founded in unison. However the

grant was probably made when the knight, William, was dying, for, after

his death, the grant was confirmed by Bishop William of St Andrews

(1202-38). This therefore happened after 1202 and before

1221, when Sir William was specifically mentioned in a confirmation as

dead. Probably at this time, John Vaux, the son of William,

made another grant in different terms. William had granted

the chapel of St Andrew's of Dirleton, but John now granted the chapel

of All Saints of Dirleton on St Andrew's day. Possibly this

meant that there was a rededication of the chapel, rather than there

being two chapels - alternately one chapel was in the village and the

other in the castle. The custodian of the castle has recently

confirmed that a possible chapel site has been found and

archaeologically investigated just outside the present castle

wall. This, if correct, favours the fact that one of the

chapels was the castle chapel which indicates that the castle was

standing in or very soon after 1221. John Vaux went on,

during the time of Bishop David of St Andrew's (1239-53), to state that

the chapel of All Saints of Dirleton was his own foundation when he

confirmed it and the mother church of Gullane to Dryburgh

abbey. This therefore confirms that there were two chapels at

Dirleton, that of St Andrew which existed in the time of John Vaux's

father, William, and that of All Saints actually built by John

Vaux. Later the grant of Eyebroughty, Dirleton, Karmurhoc and

the lands of William Gullane were confirmed as they were given at the

time when William Vaux was lord of Dirleton castle (dominus castelli de

Dyrlton). The charter was dated, but unfortunately the dating

clause was not copied into the chartulary. Quite clearly we

can see from this that Dirleton castle was standing before the death of

William Vaux in the period before 1221. The mention of an old

castle in other Vaux charters does not refer to a predecessor of

Dirleton castle as is often stated, but merely to an old hill fort.

Before 1253, when Bishop David of St

Andrew's died, John had been succeeded by Alexander Vaux as lord of

Dirleton when he made a charter witnessed by Robert Fitz Ade of

Dirleton. At some point John, the son of Robert Vaux, seems

to have been lord of Dirleton, but Alexander's son John was lord of

Dirleton before September 1267. He lived through the initial

period of the instability of the kingdom after the death of King

Alexander III (1249-86) and was still lord of Dirleton at the end of

1307. Therefore he was lord of the castle throughout the

reign of Edward I (1272-1307).

On 24 June 1291, Sir John swore fealty

and homage to Edward I of England in the chapel of Berwick

castle. Similarly on 28 August 1296, as John Vaux of the

county of Edinburgh, he again submitted to King Edward at Berwick and

attached his seal to the charter. This still exists and bears

the legend S' D'ni Joh'is de Valibus which is set around his arms, a

bend between 2 cinquefoils. This happened after Edward I had

marched into Scotland in response to the Scottish nobles, under King

John Balliol (1292-96), making common cause with Edward's enemies in

France that February. The result was the battle of Dunbar in

April and the rapid surrender of all opposition in Scotland for the

time being. These renewed submissions of fealty came to be

known as The Ragman Roll. However, Andrew Moray, the nephew

of William Moray of Bothwell castle, refused to surrender and defeated

King Edward I's army at Stirling Bridge the next year. It was

immediately after the battle that Prince

Edward wrote to the king,

telling him that as Earl Warenne and Hugh Cressingham (Hugh had

been killed at Stirling Bridge) had written that Sir John Vaux had

lately conducted himself well in the king's service in Scotland and

asked to serve abroad, that he was to be allowed his lands back if

Edward thought fitting and if sufficient security was given.

Possibly this resulted in Dirleton castle being returned to

John. Despite this, the castle, if not John, seems to have

gone over to the rebels either late this year or early the

next. Consequently, in the early summer of 1298, Edward and

an army returned to deal with the renewed opposition that had sprung up

after Moray and William Wallace's victory.

Soon after 25 June 1298, Dirleton and

two other nearby castles, were besieged by Bishop Beck of Durham on

behalf of King Edward in response to the uprising of the Scottish

barons. The castle garrison resisted the bishop's men

stubbornly and little progress was made due to a lack of wood to make

siege engines as well as a lack of victuals for the

besiegers. John Marmaduke was sent to report this to the

king, who accused the bishop of being pusillanimous. However

3 ships then arrived with supplies and the castle surrendered on the

terms that the garrison should keep their lives and their

members. With the 3 castles surrendered the bishop returned

to his king with glory. The royal army then went on to defeat

Wallace's army at Falkirk on 22 July. Therefore the siege of

Dirleton and its two comrades (Hailes and Waughton?) proved

short-lived. It is a pity we cannot be certain as to what

happened to John Vaux during this siege, but it appears that he

remained King Edward's man, for on 30 October 1300, the king ordered

Sir John to provide Dirleton castle ‘with men and victuals

and to see that the castellans of this place attacks the enemy with all

force and makes no truce under pain of forfeiture to the

king'. John was still supporting his king on 9 February 1304

when he was with a purely Scottish army that forced the capitulation of

the barons under John Comyn at Strathorde in Fifeshire that

day. It would seem likely, however, that at this point

Dirleton castle was in the king's hands, for on 6 November 1299 one Sir

Robert Mandlee promised to repay £5 which had been given to

him on the orders of King Edward between 27 June and 8 September,

‘for the provisioning of my castle of Dirleton

(Driltone)'. King Edward I performed similar actions in Wales

in keeping Dinefwr and Llandovery castles in his own hands, while

returning the surrounding lands to their natural lords. On 32

October 1300, a further £40 was given to a clerk, William

Rue, for provisioning the castles of Edinburgh and Dirleton.

On 25 October Reginald Cheyne of Duffus castle and John Vaux were

recorded as being justiciars of the king beyond the mountains of

Scotland, for which John received £20.

Soon after 25 June 1298, Dirleton and

two other nearby castles, were besieged by Bishop Beck of Durham on

behalf of King Edward in response to the uprising of the Scottish

barons. The castle garrison resisted the bishop's men

stubbornly and little progress was made due to a lack of wood to make

siege engines as well as a lack of victuals for the

besiegers. John Marmaduke was sent to report this to the

king, who accused the bishop of being pusillanimous. However

3 ships then arrived with supplies and the castle surrendered on the

terms that the garrison should keep their lives and their

members. With the 3 castles surrendered the bishop returned

to his king with glory. The royal army then went on to defeat

Wallace's army at Falkirk on 22 July. Therefore the siege of

Dirleton and its two comrades (Hailes and Waughton?) proved

short-lived. It is a pity we cannot be certain as to what

happened to John Vaux during this siege, but it appears that he

remained King Edward's man, for on 30 October 1300, the king ordered

Sir John to provide Dirleton castle ‘with men and victuals

and to see that the castellans of this place attacks the enemy with all

force and makes no truce under pain of forfeiture to the

king'. John was still supporting his king on 9 February 1304

when he was with a purely Scottish army that forced the capitulation of

the barons under John Comyn at Strathorde in Fifeshire that

day. It would seem likely, however, that at this point

Dirleton castle was in the king's hands, for on 6 November 1299 one Sir

Robert Mandlee promised to repay £5 which had been given to

him on the orders of King Edward between 27 June and 8 September,

‘for the provisioning of my castle of Dirleton

(Driltone)'. King Edward I performed similar actions in Wales

in keeping Dinefwr and Llandovery castles in his own hands, while

returning the surrounding lands to their natural lords. On 32

October 1300, a further £40 was given to a clerk, William

Rue, for provisioning the castles of Edinburgh and Dirleton.

On 25 October Reginald Cheyne of Duffus castle and John Vaux were

recorded as being justiciars of the king beyond the mountains of

Scotland, for which John received £20.

Back in the south during April 1306,

Earl Aymer Valence of Pembroke was put in charge of the east side of

Scotland with orders to repress the rebellion of Robert

Bruce. As part of this exercise he was ordered to seize

Dirleton castle with all its appurtenances, lands and tenements with

all the goods and chattels found there. The fortress was then

to be munitioned and handed over to the brother of John

Kingston. Despite this it is certain that Vaux did not go

over to the cause of Robert Bruce, for on 11 June 1307, in one of his

last acts, King Edward sent John 4 quarters of wheat and 6 barrels of

wine, to help him and his Scottish and Welsh allies hunt down Bruce

supporters around Ayr. Further, in July 1304, one William

Vaux was recorded as taking part in the siege of Stirling castle under

Edward I - his colours were argent an escutcheon within an orle of

martlets gules. It is unlikely that this was John's son and

heir, as these arms are quite different to those attested on the Ragman

Roll. On 30 September 1307 John was one of the 8 Scottish

barons asked by King Edward II (1307-27) to march into Galloway and

crush the rebellion of Robert Bruce who was burning and plundering the

land as well as forcing the inhabitants to rebel - according to 3

Scottish magnates there. The final reference to John comes on

14 December 1307, when he was one of 26 Scottish barons asked to aid

the earl of Richmond in maintaining the king's peace in

Scotland. Perhaps he was doing this when he met his end.

In 1311 payments for repairing Dirleton

cease, so presumably it had been taken for Robert the Bruce.

It was then probably slighted in accordance with that king's

policy. Dirleton may have been without a lord at this time,

although John's son, William, was lord by 1330. Indeed he is

quite possibly the William Vaux who, with three valets, was on his way

into Scotland on 2 June 1314. Therefore William may well have

fought on the losing side at Bannockburn, perhaps just after he came of

age. It also seems likely that this William was dead by 12

October 1331 when Edward III remitted £53 of his debts on

behalf of his widow, Bourge, who was in the service of Queen Joan of

Scotland, Edward's sister.

By 1336 the castle had changed hands

again, presumably after Edward Balliol, the son of King John Balliol,

invaded the country and defeated the regents for King David

II. On 13 October 1335, Dirleton (Drilton) was said to be

worth £160 in extent, but no survey of the land was held as

Gilbert Talbot held the barony as the gift of the king of

Scots. Possibly this was due to the death of William before

this date. William was certainly dead before 1346 and

Dirleton castle passed with his lands to his daughter, Christian, who

was married to John Halyburton. It is unfortunate that no

survey was carried out in 1335, for if this had survived it would have

told us what condition the castle was truly in. It is said

that the Halyburtons proceeded to rebuild the castle once they had

acquired it and that previously it had been ruinous.

John Halyburton of Dirleton was killed

at the first battle of Nisbet in 1355 while helping the lords of Ramsay

of Dalhousie, Dunbar of Dunbar castle and Douglas [of Tantallon

castle?], defeat the English garrison from Norham castle.

Later, in 1363, Douglas and Dunbar turned on the Halyburtons and seized

Dirleton castle during their rebellion against King David II in

vengeance for his earlier attack on Kildrummy castle. This

led to the battle of Lanark where Douglas and Dunbar were defeated by

King David and forced to sue for peace. Dirleton was then

returned to the Halyburtons. In 1382 another John Halyburton,

as lord of Dirleton, asked for and received the protection of King

Richard II of England for his castle and barony of Dirleton.

At the second battle of Nisbet in 1402 John

Halyburton of Dirleton, along with the Lauders of North Berwick, the

Hepburns of Hailes and the Cockburns, were defeated and captured by the

rebel Dunbars and their English ally, Percy 'Hotspur'.

Halyburton died of disease soon after his liberation. Five

years later the Halyburtons helped the rebel Sinclairs of Herdmanston,

together with the Douglases under the command of Albany, rout the royal

army at the battle of Long Hermiston Moor west of Edinburgh in

1406. The destruction of the royal army did, though, allow

the young Prince James to slip away by sea from his pursuing enemies to

Bass Rock and later be captured by the English. When he

returned many years later he inflicted a terrible revenge on his

pursuers at Stirling and Tantallon castles.

In 1505 King James IV visited Dirleton

castle and gave money to the masons. It has been presumed

that they were working on the east range. In 1515 Dirleton

castle and one third of the barony passed to the Ruthven family through

marriage. Presumably they continued the work at the west end of

the castle which was to become known as the Ruthven Range and is built

into the keep cluster. This is said to be an almost exact

copy of their townhouse in Perth where the 'Gowrie Conspiracy' would

take place in 1600. Also added at this time were the stables,

a beehive dovecot, while the palisade around the adjoining town was

replaced with a barmkin wall protected by gun-loops. The

Ruthvens, supporters of Lord Darnley, were involved in the murder of

Mary Queen of Scots' favourite, David Riccio, at Holyrood palace in

1566. They later proceeded to seize King James VI in 1582 at

Ruthven castle. Ruthven was executed in 1585 for another plot

and his wife, Dorothea, surrendered the castle which was turned over to

the earl fo Arran. In May 1585 he entertained the king in the

castle for 12 days. The next year the castle was returned to

the surviving Ruthvens, who attempted to capture the king again in 1600

during the so-called 'Gowrie Conspiracy'. The failure of this

plot resulted in the deaths of the two Ruthven brothers and the capture

of Dirleton by royal forces once more, although this time the countess

was allowed to remain in the castle, her remaining sons fleeing the

country.

In 1650 the castle was used as a base to

disrupt the supply lines of Oliver Cromwell's invasion of

Scotland. It was subsequently besieged on 9 November

1651. The attack was recorded in a letter:

That General Monck with a party of 1,600

was sent to take Derlington house, a nest of moss-troopers who killed

many soldiers of the army. That Major General Lambert came

before the house and cast up batteries the same night, so that their

great guns were ready to play the next morning by the break of

day. That their great shot played, and that the fourth shot

of their mortar piece tore the inner gate, beat down the drawbridge

into the moat and killed the lieutenant of the moss-troopers so that

they called for quarter which would not be given them, nor would they

agree to surrender to mercy, but upon reverence, which was consented

unto. That they took the governor and the captain of the

moss-troopers and 60 soldiers. That two of the most notorious

of them and the captain were shot to death upon the place.

They took in it many arms, 60 horse which they had taken from the

English, and released 10 English prisoners and demolished the house.

Despite the supposed demolition the castle was used as a hospital

during the rest of the campaign. Finally, in 1663 the castle,

in a slighted state, passed to the Nisbet family. They chose

to abandon the fortress as a residence and build a new modern house

nearby.

Description

Description

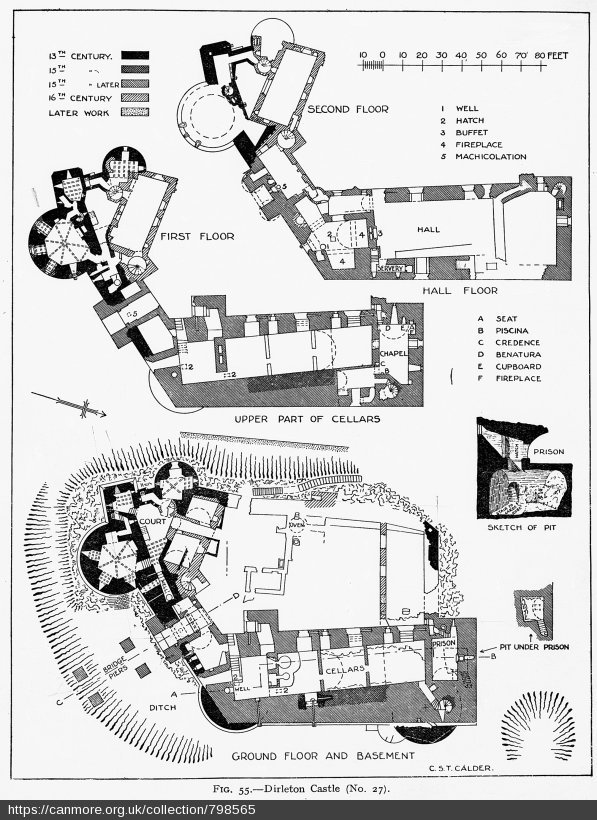

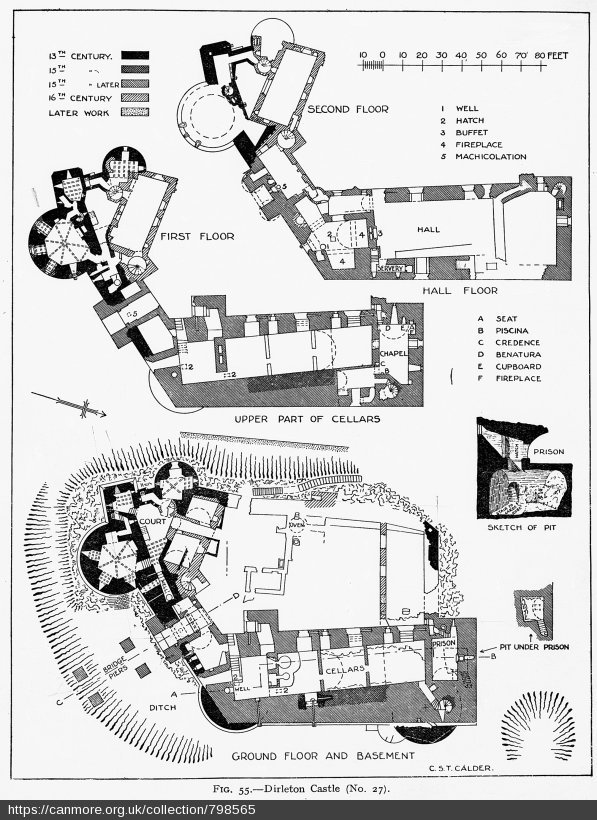

Set some 20 miles east of Edinburgh,

Dirleton castle, high on its

rocky knoll overlooking the pleasant herbaceous gardens,

strikes an imposing sight. Originally the castle surrounds

were said to be marshy. The castle rock dictated the peculiar

shape of the castle and was further protected by a great ditch to the

south and east. It would appear that the first entrance was to

the east,

and a new gate was made further south when the original was blocked in

the

late fourteenth century with the building of the Halyburton

range. The west

side of the castle is reduced to its foundations. Possibly

these foundations are original.

The main ward, or bailey of the castle,

was protected by four or possibly five round towers (there may have

been a tower to the north-west, but no trace of it now remains). Of

those that definitely survive, the three to the east seem roughly the same

size, while the one to the less accessible west is smaller. All

these towers were built from the base of the rock upwards.

There were a further two square towers on either side of the south tower

which went to form what has been described as a ‘cluster

keep'. On top of the rock was built a diamond shaped ward

with a battlemented curtain wall joining the towers together.

Much of this castle has been destroyed, but one large (35' diameter)

and one small round tower (25' diameter) remain largely

intact. With two rectangular towers they go to form the

‘cluster keep' to the west. The largest D shaped tower

has a polygonal interior and once rose three storeys high, the lowest

two floors being vaulted. The upper room still contains its

original embrasures with stone window seats, although the windows

themselves have been replaced. There is a spiral stairway in

the flat north wall of the tower, while the rectangular east turret, which is

more of an internal thickening of the wall than a true tower, contained

a well. Between the tower and turret was a postern doorway,

set high in the curtain wall. The west square turret has unusual

chamfered corners. The possibly twelfth century parts of Castell

Carreg Cennen in Wales are similar to this. The turret

appears to have contained lodgings, the upper room having holes in the

vaulting to allow the smoke from braziers to escape upwards.

The smaller round tower to the west has lost its upper storey as is still

evidence from the tooling on the Ruthven work next to it.

The top of the main tower has been

lowered and modified to form a seventeenth century gun battery, the earthen defences

of which were removed in the twentieth century clearances of the site.

The north side of the cluster keep has been much damaged by the adding of a

lodge in the Ruthven era. The surviving loops are all fish

tailed, a form that first appears in the mid twelfth century and continued in

use until the mid thirteenth when more elaborate loops became

common. The archways are generally pointed and

segmental. All the early masonry is ashlar faced rubble,

which suggests that much money went into the original construction.

Traces of 2 more round towers exist to

the south under the later east range, the north tower possibly having had a stair

blister to the south which was uncovered when the site was cleared in the

1920s. Built into the interior of the later east range is a

stretch of original curtain which lay between the 2 demolished round

towers. This is pierced by the remains of a

‘hole-in-the-wall' style gateway complete with portcullis

grooves. This would appear to be the original castle

entrance. It was blocked up when the wall was incorporated

into the new east range which was built from the ditch bottom upwards so

that its massive walls would not intrude upon the limited space

available on the rock summit. The architect sensibly used the

gap left by the original castle gate to make a fireplace and used the

portcullis groove to make a flue. The curtain wall at the north

end of the east range is a full 22' thick, incorporating as it does the

original castle wall. The south end is only 13' including the

original 8' curtain.

The new work, reasonably considered to

be that undertaken by the Halyburton family, consisted of a new

projecting rectangular gatehouse with conical roofed bartizans

(somewhat like the present entrance to Dalhousie castle) and the east

range which consisted of a new kitchen and great hall with

chapel. The main gate was a larger

‘hole-in-the-wall' style gatetower. It is similar,

but much smaller to the one found at Tantallon castle. The

front consists of a high, pointed arch which is flanked by the remains

of bartizans, small round turrets, at the top. The gateway

was protected by a drawbridge, portcullis, and three sets of doors

protected by a murder hole overhead. The interior arch was a

particularly Scottish style of Romanesque (a rounded arch).

It has therefore been suggested that this was part of the earlier Vaux

castle reused as the curtain on the north side of the gatehouse also

appears to be early work with two loops through it. However,

other doorways in the east range and indeed in the Ruthven work have the

same style and although they are smaller than the gate arch, there is

no reason to dismiss a Halyburton construction date of the mid fourteenth century.

The new work, reasonably considered to

be that undertaken by the Halyburton family, consisted of a new

projecting rectangular gatehouse with conical roofed bartizans

(somewhat like the present entrance to Dalhousie castle) and the east

range which consisted of a new kitchen and great hall with

chapel. The main gate was a larger

‘hole-in-the-wall' style gatetower. It is similar,

but much smaller to the one found at Tantallon castle. The

front consists of a high, pointed arch which is flanked by the remains

of bartizans, small round turrets, at the top. The gateway

was protected by a drawbridge, portcullis, and three sets of doors

protected by a murder hole overhead. The interior arch was a

particularly Scottish style of Romanesque (a rounded arch).

It has therefore been suggested that this was part of the earlier Vaux

castle reused as the curtain on the north side of the gatehouse also

appears to be early work with two loops through it. However,

other doorways in the east range and indeed in the Ruthven work have the

same style and although they are smaller than the gate arch, there is

no reason to dismiss a Halyburton construction date of the mid fourteenth century.

The east range is thought to have been

built by the Halyburtons in the 150 years before 1515. The

large kitchens occupy the south-east angle of the castle and have two 13' wide

fireplaces for cooking and a circular vent in the vaulted

ceiling. Hatches in the floor give access to a well 38' deep

as well as cellars below. The adjacent passage linked the

kitchen to the hall which runs the length of the east side of the

castle. It appears that originally the east range ended in an

octagonal tower built on the site of the original circular north

tower. However this was demolished and the range continued to

the north into the ditch with a projecting rectangular

towerhouse. It has been thought that the spiral stair in the

thick east wall of this represents the stair from the older round or

octagonal tower. However this would be an unlikely position

for such a stair - in the exposed north face of the earlier

tower. Only the basement of the towerhouse now survives as a

single tunnel vault with low walls subdividing the area into

stores. At the north end is a vaulted prison with a rock-cut

oubliette 11' square beneath. Above the prison, but still

within the basement, is a vaulted chapel with attached priest's

chamber. Perhaps this towerhouse is the part masons were

working on in 1505. Certainly the 2 north windows are of a

different style to those in the rest of the east range. There

are scant traces of the original castle wall in the foundations of the north curtain.

All this Halyburton work tends to be

characterised by rubble-built walls with rectangular openings, although

some doorways are Romanesque (rounded). The fine corner

quoins are of the same stone as the ashlar work of the earlier

castle. The idea that the east range was built by the

Halyburtons is confirmed by their coat of arms displayed above the

stone buffet in the south wall of the great hall.

After 1515 the Ruthven range, a

semblance of a grand renaissance house, was added to the north side of

the

keep cluster. Some of this stands upon the original castle,

the join between the two being clearly visible to the north-west.

This was intended to provide much more comfortable accommodation in a

position that overlooked the extensive gardens being developed to the

west. The original castle bears similarities to the great,

supposedly thirteenth cenury castles of Kildrummy, Bothwell, Caerlaverock,

Inverlochy, Lochindorb and Rothesay.

Why not join me at Dirleton and other Great Scottish Castles this Spring? Information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2016

Paul Martin Remfry

Soon after 25 June 1298, Dirleton and

two other nearby castles, were besieged by Bishop Beck of Durham on

behalf of King Edward in response to the uprising of the Scottish

barons. The castle garrison resisted the bishop's men

stubbornly and little progress was made due to a lack of wood to make

siege engines as well as a lack of victuals for the

besiegers. John Marmaduke was sent to report this to the

king, who accused the bishop of being pusillanimous. However

3 ships then arrived with supplies and the castle surrendered on the

terms that the garrison should keep their lives and their

members. With the 3 castles surrendered the bishop returned

to his king with glory. The royal army then went on to defeat

Wallace's army at Falkirk on 22 July. Therefore the siege of

Dirleton and its two comrades (Hailes and Waughton?) proved

short-lived. It is a pity we cannot be certain as to what

happened to John Vaux during this siege, but it appears that he

remained King Edward's man, for on 30 October 1300, the king ordered

Sir John to provide Dirleton castle ‘with men and victuals

and to see that the castellans of this place attacks the enemy with all

force and makes no truce under pain of forfeiture to the

king'. John was still supporting his king on 9 February 1304

when he was with a purely Scottish army that forced the capitulation of

the barons under John Comyn at Strathorde in Fifeshire that

day. It would seem likely, however, that at this point

Dirleton castle was in the king's hands, for on 6 November 1299 one Sir

Robert Mandlee promised to repay £5 which had been given to

him on the orders of King Edward between 27 June and 8 September,

‘for the provisioning of my castle of Dirleton

(Driltone)'. King Edward I performed similar actions in Wales

in keeping Dinefwr and Llandovery castles in his own hands, while

returning the surrounding lands to their natural lords. On 32

October 1300, a further £40 was given to a clerk, William

Rue, for provisioning the castles of Edinburgh and Dirleton.

On 25 October Reginald Cheyne of Duffus castle and John Vaux were

recorded as being justiciars of the king beyond the mountains of

Scotland, for which John received £20.

Soon after 25 June 1298, Dirleton and

two other nearby castles, were besieged by Bishop Beck of Durham on

behalf of King Edward in response to the uprising of the Scottish

barons. The castle garrison resisted the bishop's men

stubbornly and little progress was made due to a lack of wood to make

siege engines as well as a lack of victuals for the

besiegers. John Marmaduke was sent to report this to the

king, who accused the bishop of being pusillanimous. However

3 ships then arrived with supplies and the castle surrendered on the

terms that the garrison should keep their lives and their

members. With the 3 castles surrendered the bishop returned

to his king with glory. The royal army then went on to defeat

Wallace's army at Falkirk on 22 July. Therefore the siege of

Dirleton and its two comrades (Hailes and Waughton?) proved

short-lived. It is a pity we cannot be certain as to what

happened to John Vaux during this siege, but it appears that he

remained King Edward's man, for on 30 October 1300, the king ordered

Sir John to provide Dirleton castle ‘with men and victuals

and to see that the castellans of this place attacks the enemy with all

force and makes no truce under pain of forfeiture to the

king'. John was still supporting his king on 9 February 1304

when he was with a purely Scottish army that forced the capitulation of

the barons under John Comyn at Strathorde in Fifeshire that

day. It would seem likely, however, that at this point

Dirleton castle was in the king's hands, for on 6 November 1299 one Sir

Robert Mandlee promised to repay £5 which had been given to

him on the orders of King Edward between 27 June and 8 September,

‘for the provisioning of my castle of Dirleton

(Driltone)'. King Edward I performed similar actions in Wales

in keeping Dinefwr and Llandovery castles in his own hands, while

returning the surrounding lands to their natural lords. On 32

October 1300, a further £40 was given to a clerk, William

Rue, for provisioning the castles of Edinburgh and Dirleton.

On 25 October Reginald Cheyne of Duffus castle and John Vaux were

recorded as being justiciars of the king beyond the mountains of

Scotland, for which John received £20. Description

Description The new work, reasonably considered to

be that undertaken by the Halyburton family, consisted of a new

projecting rectangular gatehouse with conical roofed bartizans

(somewhat like the present entrance to Dalhousie castle) and the east

range which consisted of a new kitchen and great hall with

chapel. The main gate was a larger

‘hole-in-the-wall' style gatetower. It is similar,

but much smaller to the one found at Tantallon castle. The

front consists of a high, pointed arch which is flanked by the remains

of bartizans, small round turrets, at the top. The gateway

was protected by a drawbridge, portcullis, and three sets of doors

protected by a murder hole overhead. The interior arch was a

particularly Scottish style of Romanesque (a rounded arch).

It has therefore been suggested that this was part of the earlier Vaux

castle reused as the curtain on the north side of the gatehouse also

appears to be early work with two loops through it. However,

other doorways in the east range and indeed in the Ruthven work have the

same style and although they are smaller than the gate arch, there is

no reason to dismiss a Halyburton construction date of the mid fourteenth century.

The new work, reasonably considered to

be that undertaken by the Halyburton family, consisted of a new

projecting rectangular gatehouse with conical roofed bartizans

(somewhat like the present entrance to Dalhousie castle) and the east

range which consisted of a new kitchen and great hall with

chapel. The main gate was a larger

‘hole-in-the-wall' style gatetower. It is similar,

but much smaller to the one found at Tantallon castle. The

front consists of a high, pointed arch which is flanked by the remains

of bartizans, small round turrets, at the top. The gateway

was protected by a drawbridge, portcullis, and three sets of doors

protected by a murder hole overhead. The interior arch was a

particularly Scottish style of Romanesque (a rounded arch).

It has therefore been suggested that this was part of the earlier Vaux

castle reused as the curtain on the north side of the gatehouse also

appears to be early work with two loops through it. However,

other doorways in the east range and indeed in the Ruthven work have the

same style and although they are smaller than the gate arch, there is

no reason to dismiss a Halyburton construction date of the mid fourteenth century.