Carcassonne City

After the fall of Spain in 711 the Saracens took the city in 725, but

were expelled again by Pepin the Short in 759-60. It has

therefore been assumed that the early counts of Carcassonne were of

Visigothic extraction because their names, viz Oliba and Dela were

Visigothic. It has also been assumed by some that they were of

the same family. However, as it was unusual in Visigothic and

Carolingian lands for fiefdoms to be hereditary it seems more likely

that these were random individuals. Certainly there is no

reliable genealogy of the early counts. In 793 Count William of

Toulouse was killed at the battle of Carcassonne fighting off Muslim

attacks. During the ninth century the suzerainty of Carcassonne

is uncertain, possibly belonging to Catalonia. Bello (d.812)

seems to have been count of Carcassonne from about 790 and is claimed

as the founder of the Bellonid dynasty that ruled both Carcassonne and

the Razes to the south. Certainly by the end of the ninth century the counts of

Carcassonne owed allegiance to Toulouse, rather than Charlemagne

(d.814) as Bello had. Indeed in 872, King Charles II of the

Franks granted Carcasonem and Rhedas to Count Bernard of Toulouse

(d.874). From then on Carcassonne was certainly a part of his

county. This seems to have ended the dispute over the district in favour of the counts of Toulouse.

The death of Count Acfred II of Carcassonne (908-34) ended the possible

first comital family, although it is suggested that his daughter,

Arsinde, married Count Arnaud Comminges (d.957) and took the title to

her son, Count Roger of Carcassonne (d.1011+). As none of the

later counts used the names of the earlier counts, viz. Oliba, Acfred

or Sunifred, it may be better to assume that the second family had no

link to the first, who simply died out and were replaced. The

second family of Comminges/Carcassone died out in 1067 with the death

of Count Raymond Roger II of Carcassonne, the title passing via his

sister, Ermengarde, to her husband, Viscount Raymond Bernard Trencavel

of Albi and Nimes (d.1074). Their son, Bernard Aton Albi

(d.1129), only inherited Carcassonne in 1099 on the death of his

dowered mother, Ermengarde Carcassonne. He was using the title

viscount of Carcassonne by 1101. The overlordship of Carcassonne

meanwhile passed to the counts of Barcelona, who the counts of

Carcassonne played successfully off against the counts of

Toulouse. Both these larger powers therefore straddled the lands

of Carcassonne. In 1174 the counts of Barcelona became kings of

Aragon, changing the balance of power in the region. The status

of the Bezier lords of Carcassonne, as underlords of the counts of

Barcelona, was subsequently confirmed in November 1179 when Viscount

Roger Bezier of Carcassonne (d.1194), the grandson of Bernard Aton

Albi, confirmed his homage to King Alfonso II of Aragon (d.1195).

Indeed King Peter II of Aragon (d.1213) appeared at Carcassonne in 1204

for another inconclusive debate between the Cathars and the

Catholics. A second debate occurred at Carcassonne in 1206 which

was lively, but equally as pointless. Finally, after a dispute

between Peter Castelnau and Raymond VI of Toulouse (d.1222), Peter was

murdered by an unknown assassin and Raymond was excommunicated.

As a result the pope called for the Albigensian crusade to avenge

Peter's murder, of which he accused Count Raymond. By these means

he proposed to deal with the Cathar problem permanently.

In 1209 Count Raymond of Toulouse accepting a scourging by the church

to save his lands from invasion. Raymond-Roger Trencavel Beziers,

the great-grandson of Bernard Aton Albi (d.1129) and son of the Roger

(d.1194) who had confirmed his vassalage to King Alphonso (d.1195), was

made of sterner stuff and proposed resistence. As a staunch

Catholic the 24 year old thought himself in a strong position, despite

the fact of his having dethroned the bishop of Carcassonne and replaced

him with his own nomination - a man who's mother, sister and 3 brothers

were all parfaits. Raymond-Roger asked for talks concerning his

conjectured joining of the Crusade, but the papal legate, Abbot Arnaud

Amalric (d.1225), dismissed his appeal and marched on Beziers, while

Raymond-Roger fell back on Carcassonne. After the 22 July

massacre at Beziers, Raymond-Roger burned the surrounds of his city and

prepared for siege, the first Crusaders arriving on 1 August. On

the next day the suburb of Bourg fell and King Peter of Aragon (d.1213)

arrived and asked for terms for his vassal, Raymond-Roger. Again

the request was refused with Arnaud merely offering the lord permission

to retire and leave his city to its fate. On 15 August

Raymond-Roger, his city defences battered, but unconquered, agreed to

surrender Carcassonne, apparently on condition that all, including

Cathars, could leave the city unmolested, but without any

possessions. However, it would seem that Arnaud partially broke

this agreement and imprisoned Raymond-Roger in his own dungeon where he

died 3 months later on 10 November, allegedly of dysentery, but thought

to be murdered. The inhabitants, all but naked, were allowed to

leave.

After some deliberation Arnaud replaced Raymond-Roger as lord of

Carcassonne and installed Simon Montfort (d.1218), a claimant to the

earldom of Leicester, in his place. After much negotiation Simon

managed to gave his homage for Beziers and Carcassonne to King Peter II

of Aragon (d.1213), who in turn gave his son, later to be King James I

of Aragon (d.1276), into Simon's custody at Carcassonne. After

his father's death against Simon Montfort at the battle of Muret the

Templars had to negotiate for James' release from the fortress.

The kings of Aragon finally seem to have granted their rights in

Carcassonne away in 1262, although in reality they had lost the city in

1209.

Raymond-Roger (d.1209), the ex.lord of Carcassonne, left a 2 year old

son, Raymond Trencavel (1207-63), who was disinherited. In 1223

Raymond returned and besieged Amaury Montfort, the son and heir of

Simon, in the fortress. He finally took possession of city and

castle when Amaury returned to the Ile de France

in 1224. Despite this, after 24 October 1224, King Louis VIII

(d.1226) confirmed his disinheritance and Raymond withdrew to Aragon in

1226 when the king took city and castle. In 1240 he, together

with Oliver Termes and Peter Fenouillet

and other faidit, failed to take the city during a 24 day September

siege. Consequently he renounced his claim to it in 1246 when

making peace with the Crown. Two years later the king ordered the

suburbs of the city to moved to the other bank of the river and founded

the Ville Basse. It then became a royal border fortress with

Spain after the 1258 treaty of Corbeil which defined their power in the

district.

In 1355 the city repulsed the Black Prince, although he destroyed the

lower town or Ville Basse and laid waste the district. After this

the Ville Basse was fortified on the west side of the river and the

final parts of the inner enceinte made under the regency of Duke Philip

le Bold (d.1404). Finally in 1659, the treaty of the Pyrenees

removed the military reason behind the fortress and it soon fell into

ruins, only narrowly escaping demolition in the nineteenth century,

after which it was terribly rebuilt and modernised by Viollet le Duc.

Carcassonne City Defences

These consist of 2 concentric walls with 54 towers and barbicans making

an inner walkwalk 0.8 of a mile long and an outer one of just over a

mile in circumference. The outer walls with 16 towers date to

after the city's siege by Raymond Trencavel in 1240. In the main

enceinte there are 27 towers plus 11 in the castle. In the outer

ward these vary from small D shaped towers to large round ones like the

Tour de la Vade, as well as varied posterns like the horseshoe shaped

barbicans of Notre Dame and St Louis. The loops in these towers

appear to be without sighting slits and often have rectangular or fish

tailed basal oillets. The wall masonry, where it has not been

‘restored', looks similar to the lowest levels of the inner

ward. As such it could be that the base of the Roman walls have

been refaced in the thirteenth century. However, the scale and

manner in which the ‘Roman' walls overlie it, makes it more

likely that this is early work.

Built within the outer enceinte is the original Roman town with much of

its plan still traceable. The dates of the different phases of

the construction are still not clear and possibly never will be.

If there is a ‘prehistoric' wall then this would appear to have

been quite low, maybe originally 10-15' high. The Roman wall

would appear to have been about 25' high and the towers maybe 10'

higher. There must have been Roman gates at various points, but

none of these have survived, no doubt being overbuilt by later

works. The thirteenth century walls were about 30' high and the

work of Philip le Bold (d.1404), even higher, especially his towers,

like the Narbonnaise gate.

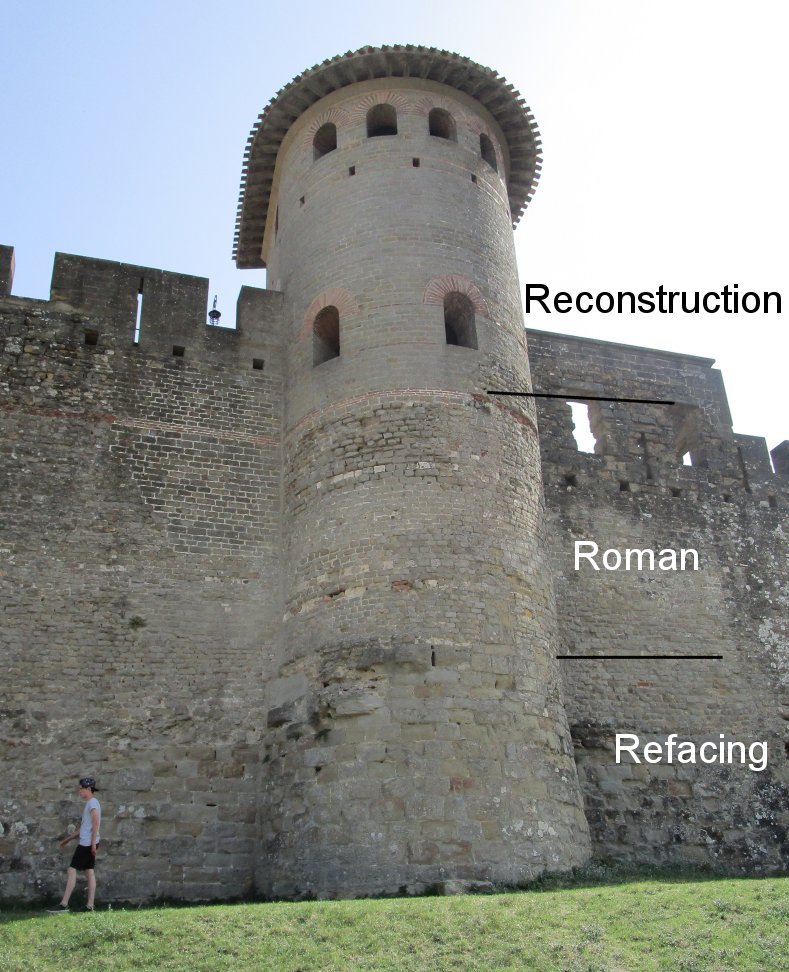

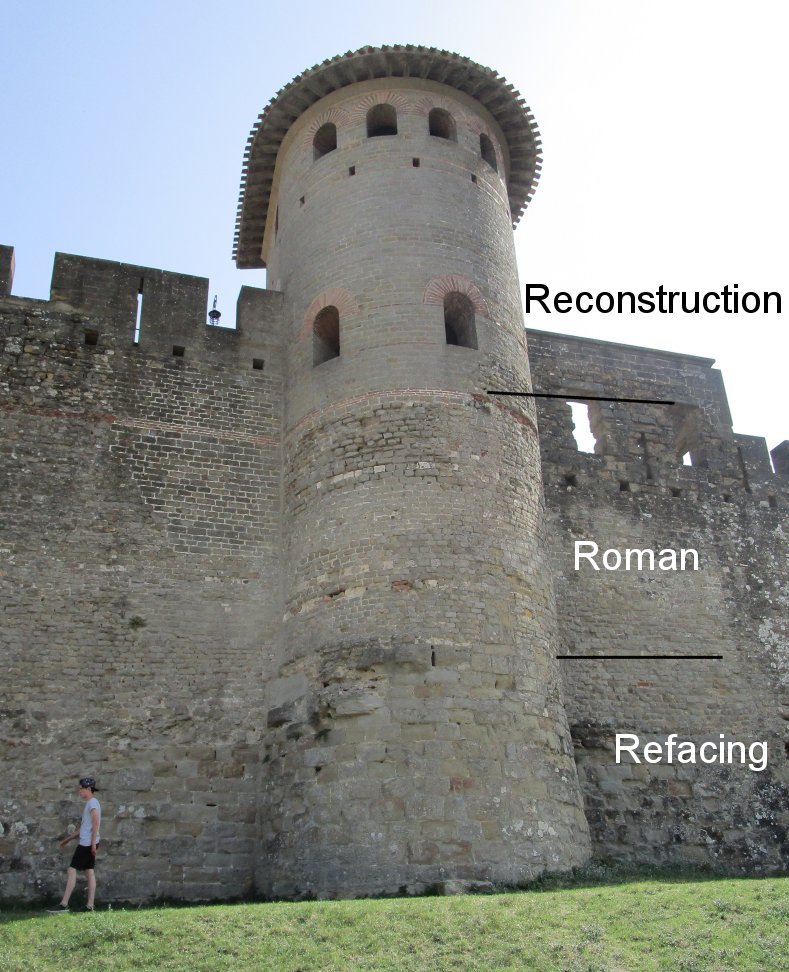

A

photograph of the Charpenterie Tower gives some idea of the early

phases. It seems possible that the base of the walls are Roman

with thirteenth century refacing over it. This walling consists

of good quality masonry of rectangular blocks surrounding a rubble

core. This walling style is similar to the Roman layout at Caerwent in Wales which has no tiled levelling layers, but dissimilar to Portchester and Pevensey,

which have the tile levelling layers. At Carcassonne, above this

probable refacing, are smaller blocks with red tile levelling

layers. This is generally taken to be the Roman phase.

However, it is possible that some or all of this might be Visigothic

and overlie the earlier Roman work. Against this is the fact that

Pevensey fort, now dated to

the 290s, has a similar build style, with little blocks and single red

tile levelling courses. The dating of Carcassonne walls to the

late fourth century is apparently traditional and based on no

scientific fact.

A

photograph of the Charpenterie Tower gives some idea of the early

phases. It seems possible that the base of the walls are Roman

with thirteenth century refacing over it. This walling consists

of good quality masonry of rectangular blocks surrounding a rubble

core. This walling style is similar to the Roman layout at Caerwent in Wales which has no tiled levelling layers, but dissimilar to Portchester and Pevensey,

which have the tile levelling layers. At Carcassonne, above this

probable refacing, are smaller blocks with red tile levelling

layers. This is generally taken to be the Roman phase.

However, it is possible that some or all of this might be Visigothic

and overlie the earlier Roman work. Against this is the fact that

Pevensey fort, now dated to

the 290s, has a similar build style, with little blocks and single red

tile levelling courses. The dating of Carcassonne walls to the

late fourth century is apparently traditional and based on no

scientific fact.

The oldest segments of the wall lie to the N&E. They commence

in the SE with the so-called Visigothic Tower and run northwards, past

the castle and around to the Tresau Tower at the eastern apex of the

site. From here to the Narbonnaise gate the bulk of the wall is

mainly fourteenth century work. After the gate the Roman wall

reappears and runs SW to just beyond the Castera Tower, with the

section around the Balthazar Tower having been rebuilt late in the

fourteenth century. This ancient work makes up at least half the

inner circuit. Obviously these works have been much repaired over

the many centuries between their building and the present day.

The original wall thickness appears to have been about 10'.

Obviously this is a lot of wall to cover for a quick summary therefore,

instead of a full description, a few pertinent points will be

made. Firstly the only surviving Roman gateway seems to be the

postern on the west side of the Moulin d'Avar Tower. The jambs of

this have been replaced, while the lower half of the tower itself

consists of the early/refacing that is discussed below on the

Connetable Tower. The head of the postern survives as an arch

consisting of sandstone springers on what appears to have been a tiled

impost. Above this the voussiors consisted of two Roman tiles

interspersed with sandstone voussiors. The wall to the west of

the doorway consists of the small Roman blocks interspersed with

occasional large snecker stones. The size of these stones would

indicate that they were an original feature of the wall and therefore

that this work may be prehistoric rather than Roman.

The

Connetable Tower gives evidence of such early work or

refurbishment. It seems to sit on either a thirteenth century

reconstruction or an earlier base of a rectangular tower. As this

base appears linked with the adjoining curtain base to the NW the

former may be more likely. Above this in the tower is some 25' of

‘Roman style' masonry which ends just below wallwalk level.

Above this is some 30' of post Roman work with regular putlog holes,

surmounted by a Viollet-le-duc folly. The same layout is apparent

on the adjoining wall to the north with its reconstructed

battlements. To the south lay a new wall, probably built under

the orders of Philip le Bold (d.1404). Behind this wall running

south to the Tresau Tower is the original Roman wall. This

connected to the rear of the D shaped Connetable Tower and seems to

have contained a mural passageway at this level entered via a large

Romanesque door with a reconstructed tile arch. Of the 2 D shaped

towers in this buried section of wall, the northern one has a

rectangular base with Roman masonry on top of it, while the southern

one has been totally refaced and has no base. The reconstruction

is similar to work at the summit of the surviving portion of the

northern tower.

The

Connetable Tower gives evidence of such early work or

refurbishment. It seems to sit on either a thirteenth century

reconstruction or an earlier base of a rectangular tower. As this

base appears linked with the adjoining curtain base to the NW the

former may be more likely. Above this in the tower is some 25' of

‘Roman style' masonry which ends just below wallwalk level.

Above this is some 30' of post Roman work with regular putlog holes,

surmounted by a Viollet-le-duc folly. The same layout is apparent

on the adjoining wall to the north with its reconstructed

battlements. To the south lay a new wall, probably built under

the orders of Philip le Bold (d.1404). Behind this wall running

south to the Tresau Tower is the original Roman wall. This

connected to the rear of the D shaped Connetable Tower and seems to

have contained a mural passageway at this level entered via a large

Romanesque door with a reconstructed tile arch. Of the 2 D shaped

towers in this buried section of wall, the northern one has a

rectangular base with Roman masonry on top of it, while the southern

one has been totally refaced and has no base. The reconstruction

is similar to work at the summit of the surviving portion of the

northern tower.

Perhaps

the best early structure in the city wall is the Marquiere Tower.

Like many of its compatriots it stands upon a square masonry

base. It then rises in 'Roman masonry' to the curtain wallwalk

height before being topped by one of Viollet-le-duc's fantasies.

However, in its upper Roman section are the remnants of 3 Roman

windows. The central one facing NE appears to be original, though

its 2 flankers to E&W have been deepened and filled to take

thirteenth century crossbow loops. Presumably the central loop

has been scooped out. The arch of all 3 survives and consists of

Roman tiles interspaced with slabs of sandstone. This style has

been copied by Viollet-le-duc throughout his 'reconstructions'.

Perhaps

the best early structure in the city wall is the Marquiere Tower.

Like many of its compatriots it stands upon a square masonry

base. It then rises in 'Roman masonry' to the curtain wallwalk

height before being topped by one of Viollet-le-duc's fantasies.

However, in its upper Roman section are the remnants of 3 Roman

windows. The central one facing NE appears to be original, though

its 2 flankers to E&W have been deepened and filled to take

thirteenth century crossbow loops. Presumably the central loop

has been scooped out. The arch of all 3 survives and consists of

Roman tiles interspaced with slabs of sandstone. This style has

been copied by Viollet-le-duc throughout his 'reconstructions'.

The works attributed to Philip le Bold (d.1404) consist of the SW

quarter of the defences from the Inquisition Tower south of the castle

to the Prison Tower in the south wall of the city. North of this

the Balthazar Tower and the surrounding curtain also look like his

work, as too are the Narbonnaise gate and the adjoining Tresau

Tower. The towers of this work are usually built of embossed

masonry and have small beaks pointing towards the enemy. This is

a style allegedly brought in by King Henry II of England at Loches.

The towers and walls attributed to Philip are also built on a more

massive scale than the rest of the military works at Carcassonne.

The Inquisition Tower in the west wall south of the Comtal Castle,

may stand on the site of a Roman tower and although the thirteenth

century Inquisition, commenced in 1233, seems to have been set in this

tower, the current exterior seems more fourteenth century judging by

the embossed masonry. However, its smaller size compared with

Philip le Bold's works and its lack of a beak, may well mean that it is

earlier and may date from the early 1200s. A letter was written

around 1285 by the Consuls of Carcassonne to Jean Galand, a Dominican

Inquisitor in the city, complaining of the conditions within the

Inquisition Tower:

… you have created a prison called "The Wall", which would be

better called "Hell". In it you have constructed small cells to

inflict pain and to mistreat people using various types of

torture. Some prisoners remain in fetters… and are unable

to move. They excrete and urinate where they are…

Some are placed on the rack; many of them have lost the use of their

limbs because of the severity of the torture… Life for

them is an agony and death a relief. Under these constraints they

affirm as true what is false, preferring to die once than to be thus

tortured multiple times.

At the NW side of the city defences lies the Comtal Castle.

Why not join me here and at other French

castles? Information on this and other tours can be found at Scholarly

Sojourns.

Copyright©2019

Paul Martin Remfry

A

photograph of the Charpenterie Tower gives some idea of the early

phases. It seems possible that the base of the walls are Roman

with thirteenth century refacing over it. This walling consists

of good quality masonry of rectangular blocks surrounding a rubble

core. This walling style is similar to the Roman layout at Caerwent in Wales which has no tiled levelling layers, but dissimilar to Portchester and Pevensey,

which have the tile levelling layers. At Carcassonne, above this

probable refacing, are smaller blocks with red tile levelling

layers. This is generally taken to be the Roman phase.

However, it is possible that some or all of this might be Visigothic

and overlie the earlier Roman work. Against this is the fact that

Pevensey fort, now dated to

the 290s, has a similar build style, with little blocks and single red

tile levelling courses. The dating of Carcassonne walls to the

late fourth century is apparently traditional and based on no

scientific fact.

A

photograph of the Charpenterie Tower gives some idea of the early

phases. It seems possible that the base of the walls are Roman

with thirteenth century refacing over it. This walling consists

of good quality masonry of rectangular blocks surrounding a rubble

core. This walling style is similar to the Roman layout at Caerwent in Wales which has no tiled levelling layers, but dissimilar to Portchester and Pevensey,

which have the tile levelling layers. At Carcassonne, above this

probable refacing, are smaller blocks with red tile levelling

layers. This is generally taken to be the Roman phase.

However, it is possible that some or all of this might be Visigothic

and overlie the earlier Roman work. Against this is the fact that

Pevensey fort, now dated to

the 290s, has a similar build style, with little blocks and single red

tile levelling courses. The dating of Carcassonne walls to the

late fourth century is apparently traditional and based on no

scientific fact. The

Connetable Tower gives evidence of such early work or

refurbishment. It seems to sit on either a thirteenth century

reconstruction or an earlier base of a rectangular tower. As this

base appears linked with the adjoining curtain base to the NW the

former may be more likely. Above this in the tower is some 25' of

‘Roman style' masonry which ends just below wallwalk level.

Above this is some 30' of post Roman work with regular putlog holes,

surmounted by a Viollet-le-duc folly. The same layout is apparent

on the adjoining wall to the north with its reconstructed

battlements. To the south lay a new wall, probably built under

the orders of Philip le Bold (d.1404). Behind this wall running

south to the Tresau Tower is the original Roman wall. This

connected to the rear of the D shaped Connetable Tower and seems to

have contained a mural passageway at this level entered via a large

Romanesque door with a reconstructed tile arch. Of the 2 D shaped

towers in this buried section of wall, the northern one has a

rectangular base with Roman masonry on top of it, while the southern

one has been totally refaced and has no base. The reconstruction

is similar to work at the summit of the surviving portion of the

northern tower.

The

Connetable Tower gives evidence of such early work or

refurbishment. It seems to sit on either a thirteenth century

reconstruction or an earlier base of a rectangular tower. As this

base appears linked with the adjoining curtain base to the NW the

former may be more likely. Above this in the tower is some 25' of

‘Roman style' masonry which ends just below wallwalk level.

Above this is some 30' of post Roman work with regular putlog holes,

surmounted by a Viollet-le-duc folly. The same layout is apparent

on the adjoining wall to the north with its reconstructed

battlements. To the south lay a new wall, probably built under

the orders of Philip le Bold (d.1404). Behind this wall running

south to the Tresau Tower is the original Roman wall. This

connected to the rear of the D shaped Connetable Tower and seems to

have contained a mural passageway at this level entered via a large

Romanesque door with a reconstructed tile arch. Of the 2 D shaped

towers in this buried section of wall, the northern one has a

rectangular base with Roman masonry on top of it, while the southern

one has been totally refaced and has no base. The reconstruction

is similar to work at the summit of the surviving portion of the

northern tower. Perhaps

the best early structure in the city wall is the Marquiere Tower.

Like many of its compatriots it stands upon a square masonry

base. It then rises in 'Roman masonry' to the curtain wallwalk

height before being topped by one of Viollet-le-duc's fantasies.

However, in its upper Roman section are the remnants of 3 Roman

windows. The central one facing NE appears to be original, though

its 2 flankers to E&W have been deepened and filled to take

thirteenth century crossbow loops. Presumably the central loop

has been scooped out. The arch of all 3 survives and consists of

Roman tiles interspaced with slabs of sandstone. This style has

been copied by Viollet-le-duc throughout his 'reconstructions'.

Perhaps

the best early structure in the city wall is the Marquiere Tower.

Like many of its compatriots it stands upon a square masonry

base. It then rises in 'Roman masonry' to the curtain wallwalk

height before being topped by one of Viollet-le-duc's fantasies.

However, in its upper Roman section are the remnants of 3 Roman

windows. The central one facing NE appears to be original, though

its 2 flankers to E&W have been deepened and filled to take

thirteenth century crossbow loops. Presumably the central loop

has been scooped out. The arch of all 3 survives and consists of

Roman tiles interspaced with slabs of sandstone. This style has

been copied by Viollet-le-duc throughout his 'reconstructions'.