Leeds

Leeds is a large castle set within a large artificial lake in a bend of the River Len in Kent half way between Dover castle and the Tower of London. It is one of the largest castles in England due to its massive water defences.

At the time of Domesday (1086) the estate of Leeds (Esledes)

was held

by Aethelwold the chamberlain from Bishop Odo of Bayeau, the king's

half-brother. There was the land for 12 ploughs there of which 2

were in the lordship. There were also 28 villagers and 8

smallholders living in the manor with 7 ploughs. There was also a

church, the remains of which are built into

the current structure within the village some distance from the castle,

though the fortress is not mentioned in the survey. Leeds church

consists of a large rectangular tower in the dimensions of a tower keep

and contains Romanesque windows and archways and is currently not

securely dated. Within the vill there were 18 slaves, 2

arpents of vines, 8 acres of meadow, woods and 20 pigs. Of more

import to the castle there

were also 5 mills belonging to the villagers. Quite possibly one of these mills was situated where the

mill in the castle barbican now stands. The total value of the

estate before 1066, when it was held by Earl Leofwin (died at

Hastings), had been £16, although this had now risen to £20 in

1086.

Between 1086 and 1100 the manor of Leeds came into the hands

of a Norman, Hamo Crevequer. Possibly this happend immediately on

the forfeiture of Bishop Odo

in 1088. In 1119 his son and successor, Robert, together with his

wife, Rose, and their son Adam, founded Leeds priory in honour of St

Mary and St Nicholas. It is said that they transferred 3

churchmen living on the castle site to the new priory at this time and

that this is the first certain mention of the castle, although where

this statement originates from is currently unknown.

Certainly no original documentation to this effect has come to light.

In 1138 Earl Robert of Gloucester rebelled against King Stephen

and

fortified the castles of Bristol and Leeds (Slede) against the crown. Leeds was

quickly reduced by King Stephen soon after Christmas and apparently

returned to Robert Crevequer, who was apparently still holding the

fortress at the time of his death around 1154. As the fortress remained

in the Crevequer family it is to be presumed that they reverted to a royal alliegence, if they had ever left it.

In 1215 the castle was again besieged

and taken during the barons' war at the end of King John's reign.

During another Baron's war in 1264-67, the castle was again lost to

royal forces and this time the lord of the manor, the last Hamo

Crevequer of Leeds

castle, was forced to exchange the castle with Roger Leybourne in

October 1268. His son, William Leybourne, in turn sold the

castle, which

was called 'The Moat' (la Mote) to Queen Eleanor for 500 marks in June

1278. It has occasionally been suggested that 'la Mote' meant

that there was a motte at the castle on the site of the gloriette.

In reality it is far more likely that the site was actually known

as 'the moat'. This far more describes the site and suits the

etymology.

After 1278 the queen made the Crevequer fortress into a royal home. This was

visited by King Edward I in 1279, 1281, 1285, 1288 and 1289. Then,

on 28 November 1290, when his first queen died, the king took over its

maintenance and in November 1291 paid for 6 carts of lead bought and

sent to Leeds by his own writ for his baths, £17 2s, plus 57s

carriage. There was a further charge of 1s 8d for transporting

the lead to the ship. He also paid for 100 Ryegate stones being

bought and taken to the castle for 6s. This was then made into

the pavement of his baths by Thomas Lamberhurst for 20s. Adam

Lamhurst was also paid 40s for some of his work in this ‘paving

of the baths and other things at Leeds'. Thomas (the Porter) was

also paid four pennies (or shillings - the account is unclear) for various works made in the

castle at the same time, while Adam Lamberhurst received 20s in part

payment for the pavement and other things he had done at Leeds. After this, the king frequented the place rarely, the

duke of Burgundy and other French ambassadors were prepared for in

1291, but did not appear, although the count of Bar stopped here in

1293. By this time the castle was held by Edward's second wife,

Margaret (d.1317).

In 1314 a violent storm damaged the glass windows of the castle to

such an extent that it required 105s to reinstate them. On Queen

Margaret's death in 1317, her step-son, King Edward II, exchanged the castle

with Bartholomew Badlesmere in 1318 without taking into account the

wishes of his wife, who appears to have had a claim upon the fortress

as heir to her step-mother-in-law. According to the official

documentation the king agreed to grant Bartholomew Badlesmere the

castle and manor of Leeds, which Queen Margaret of England, deceased,

held for life by grant of Edward I, as of the value of £21 6s 8d

yearly (32 marks) next of fixed alms, to have in return for 100 marks yearly

in land to be given to the king. For this the king received the

manor of Adderley, Salop, which was worth only £99 19s 8¼d

per annum, but its church was worth 60 marks and thus greatly exceeded

the £100 per annum required. As a result of the exchange,

in 1321 it was said that Isabella attempted to enter the castle for her

night's rest and was stoutly repulsed when on her way to

Canterbury. In consequence, on 16 October 1321, the king ordered

the sheriffs of Essex, Southampton, Surrey and Sussex to raise 1,000

men a piece and bring them to Leeds castle on the Friday after St Luke

next, with horses and arms, as the king proposed going against the

castle with Earl Aymer Valence of Pembroke, Earl John Britannia of

Richmond and other earls and magnates, to punish the disobedience and

contempt against the queen committed by certain members of the

household of Bartholomew Badlesmere and others staying in the castle by

his precept, in refusing to allow the queen to enter the castle and

hindering her doing so by armed force, which Bartholomew afterwards

approved by his letters to the queen to have been done by his knowledge,

whose familiars afterwards slew certain men of the queen's

household. The action was also said to be a personal matter and

not a matter for other barons to become involved in.

Despite this the rebel barons of Edward II moved towards the

castle but dared not fight the king with the consequence that the

castle surrendered on 1 November 1321 and 13 of the garrison were

summarily hanged by the king who resumed possession of the

fortress. On 4 November the king announced the capture of

Bartholomew Burghersh, Thomas Aldon and John Bourn, because they had

detained the castle of Ledes against the king, hindering the king's

entrance thereof, and in the surrender of the castle surrendered

themselves also to the king's will. The castle then remained a

royal fortress.

In 1413 Archbishop Thomas of Canterbury went to the

‘greater chapel of Ledys castle' and called on the castle's

holder, Lord John Oldcastle of Cobham, to answer for his adherence to

Lollardism. Sir John, despite being called in a loud voice,

refused to attend to the archbishop and instead shut himself up in his

castle which he fortified. This strongly suggests that the

greater chapel lay in the outer island and that Oldcastle was in the

gloriette, also known now as the ‘old castle'! Sir John was therefore deemed contumacious and was

excommunicated in writing. He was later imprisoned, but escaped

to Wales, before finally being executed by Henry V in 1413 after a

failed uprising. In 1422 Queen Joanna, the widow of Henry IV, was

released from captivity after accusations of witchcraft and retired to

Leeds castle where she celebrated her freedom by giving alms ‘at

the cross in the chapel within Leeds castle' worth 6s 8d. However

two celebratory feasts with her family set her back over £4

each! At the same time over £56 was spent on stocking the

castle with wine. The castle remained nominally in her hands

until it was granted to Katherine of Valois, widow of Henry V, in

1425. Probably in 1436 King Henry VI ordered the repair of the

lead work in the gloriette whilst he was staying there. In 1438-9

a survey recorded the repairing of the kitchen next to the foot bridge

to the gloriette within the castle. A further £10 was spent

on remaking a corner of the tower within the castle called the

Gloriette which had recently collapsed to the ground as well as for

repairing the defects of the said tower.

In 1441 the revamped castle saw the political trial

of Eleanor Cobham, wife of Duke Humphrey of Gloucester. She was

imprisoned for life, while in 1446 her husband too was arrested for

high treason and conveniently died soon afterwards. In 1442,

after the trial of Eleanor Cobham, a plumber worked for 25 weeks in

covering the house roofs within the gloriette. Also various earth

walls were repaired. Presumably these were half timbered walls of

wattle and dawb which graced the interior of the gloriette.

Similar walls were present at the back of the outer ward towers, of

which only one

still survives to the E. The castle survived the Civil War of

1642-46 and continued as a home into the twentieth century, being much

rebuilt and altered in the nineteenth century.

Description

The castle was divided into five separate enclosures set in an

artificial lake of nearly 15 acres, the enclosures being set against

the south-west bank. When the moat was partially drained in the nineteenth century it

was found to be over 17' deep and the only way to drain it properly

would have been to demolish a channel through one of the

barbicans. This obviously was not done.

The first portion of the defences to be encountered

when approaching from the land side was the outer barbican to the south-west of

the castle proper. This controlled the dam which kept the lake

flooded. The castle is currently approached from three

directions, west, south and east. The south and east causeways currently lead

directly to the inner barbican, thereby suggesting that they are late

additions. The approach from the west passed through an outer

barbican. This therefore was surely the original approach,

otherwise the building of the outer barbican becomes superfluous to the

defence of the castle, unless it was merely built to bring the mill

into the fortifications.

Outer Barbican

The outer barbican apparently has no protecting ditch to the north-west where

the entrance lies. Further, the gateway shows no evidence of a

drawbridge. This is a strange design considering the gateways

into the rest of the castle. It is possibly explained by the

nineteenth century suggestion that the causeway to the north-west was fortified

by weak walls

for a distance of some 180-200 feet from the gateway. Such a long

barbican is unusual, but not impossible. The main outer entrance

to the castle consists of an internally projecting rectangular

structure with a deeply recessed doorway protected by two murder holes

behind a reinstated portcullis. Such a design could be twelfth

century and

is echoed at the north gate at Chepstow castle. The stonework of the

barbican consists of large rectangular blocks that tend towards

squareness, with the holes between the blocks filled with much smaller

fragments. The inner barbican is built in the same style and the

implication is that both were planned and executed

simultaneously. They also both have regular putlog holes spaced

throughout their outer surfaces.

Next

to the gate in the east corner of the outer

barbican was a large rectangular tower which is obviously of one build

with the rest of the barbican. This tower housed the mill and was

powered by a sluice from the lake. The mill wheel was set in a

basement chamber, while above was a rectangular room with large

embrasures and loops to the west. Above this was a further room

having much smaller embrasures of a less pointed nature holding

rectangular windows. These embrasure sizes are the reverse of

what is normally expected in towers and again emphasises how dangerous

it is to date structures upon the perceived or alleged dates of their

styles. The tower would seem to date from before

1314 when repairs to the structure and mechanism of the mill in the

castle cost 16s. Presumably the whole is twelfth century with

additions.

Next

to the gate in the east corner of the outer

barbican was a large rectangular tower which is obviously of one build

with the rest of the barbican. This tower housed the mill and was

powered by a sluice from the lake. The mill wheel was set in a

basement chamber, while above was a rectangular room with large

embrasures and loops to the west. Above this was a further room

having much smaller embrasures of a less pointed nature holding

rectangular windows. These embrasure sizes are the reverse of

what is normally expected in towers and again emphasises how dangerous

it is to date structures upon the perceived or alleged dates of their

styles. The tower would seem to date from before

1314 when repairs to the structure and mechanism of the mill in the

castle cost 16s. Presumably the whole is twelfth century with

additions.

A spiral stair remains in the wall south of the tower. This

allowed access to the upper floor and wallwalk. To the SE the

outer barbican has been largely destroyed and the protecting ditch

apparently filled in. The surviving inner walls of the barbican

and mill tower are only a couple of feet thick, compared to the more

defensible 5' of the outer walls. Some part of this was

already decayed in 1314 when the stone wall at the head of the interior

lake next to the mill was found to have collapsed and the jurors could

not estimate the cost of repairs as the foundations were under water

and they could not work out an easy way to get to them.

Inner Barbican

From the outer barbican gatehouse a right-angled turn brings you to an

arched stone bridge with a loop above on the outer wall. This

bridge crosses to the inner barbican which is entered through another

gatehouse, similar to the outer barbican one, but with the internal

protrusions thickened to make two small, irregular rectangular

turrets. The gate itself is slightly recessed between the internal

towers.

On this island the irregular inner barbican rises

directly from the moat, occasionally with a strong batter. The

enceinte is also pierced on the landward side with cruciform crossbow

loops of a thirteenth century design. The whole bears some

resemblance to the barbican at Whittington, Shropshire.

Interestingly both castles were known to the Maminot family in the mid

twelfth century. The north front of the barbican has collapsed, a

state possibly dating back to before the survey of 1314 when some form

of collapse was mentioned.

There are currently two further drawbridges which

led into the inner barbican island from south and east. These are

probably later than the most powerful entrance via the outer

barbican. It is therefore likely that both are late

medieval. From the inner gatehouse a fortified bridge ran east to

the main castle island. This bridge has two arches, the

easternmost one having a drawbridge immediately before the main outer

gatehouse. One of these many bridges was the southern outer

bridge (pons exterior australis castri) that was repaired at a cost of

24s in 1314.

Outer Ward

The outer gatehouse is at the point of a ravelin-like projection on the

island and consists of a rectangular gatehouse tower, in line, but not

proud of, the outer curtain wall. This outer ward wall is again

heavily battered like the barbican walls to the south and west, though that to

the east may be buried under the current gardens which are outside the

medieval defences and were added when the island was extended in modern

times. It also had loops in it, two to the south-west still partially

remaining. The gatehouse is obviously of a different build to the

rest of the outer ward enceinte as the stonework is different.

The main curtain walls and towers consist of a rubble ashlar, while the

gatehouse has reasonably regularly laid rubble walls. The

implication is that the gatetower is the older of the two and the

island defences were built sometime after the gatehouse in better

quality stonework.

The outer gateway has two pilaster buttresses to the

front, flanking the entrance. The main gate is recessed between

these. A few feet above the gate arch the pillasters join to form

a solid front just above two holes for the drawbridge chains. A

few feet higher the front is topped by the remnants of a corbelled out

machicolation. Behind this the tower continues for a few more

feet before being truncated at what was probably battlement

height. The gatetower entrance seems always to have been

protected by gate and portcullis. Behind these the gatepassage

now runs all the way into the site of the main ward and it is uncertain

how much this has been altered over the years.

Within

the outer gatetower at first floor level was

a chamber from where portcullis and drawbridge were operated. Two

blocked up loops covering the approach could still be discerned in the

nineteenth century. Behind the gatetower and adjacent to it are a

series of

more modern buildings which make the original layout of this area

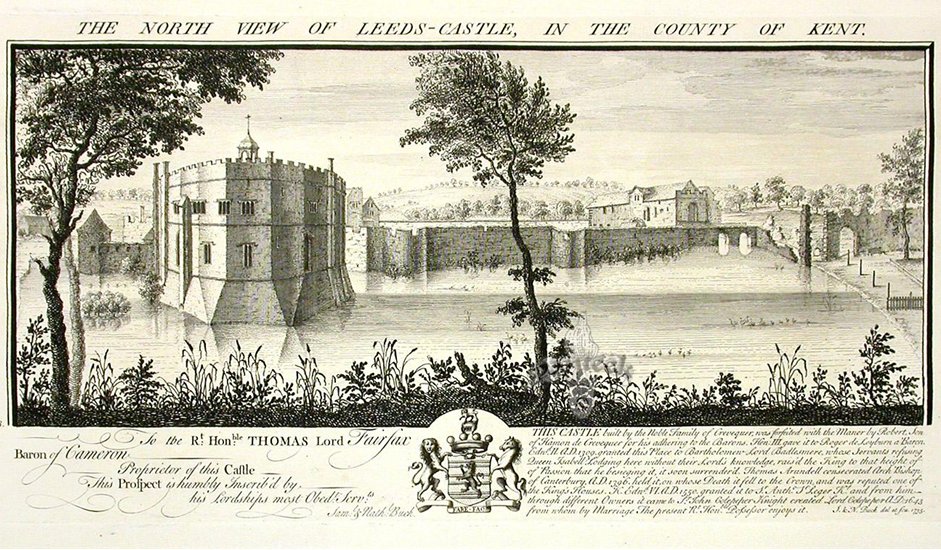

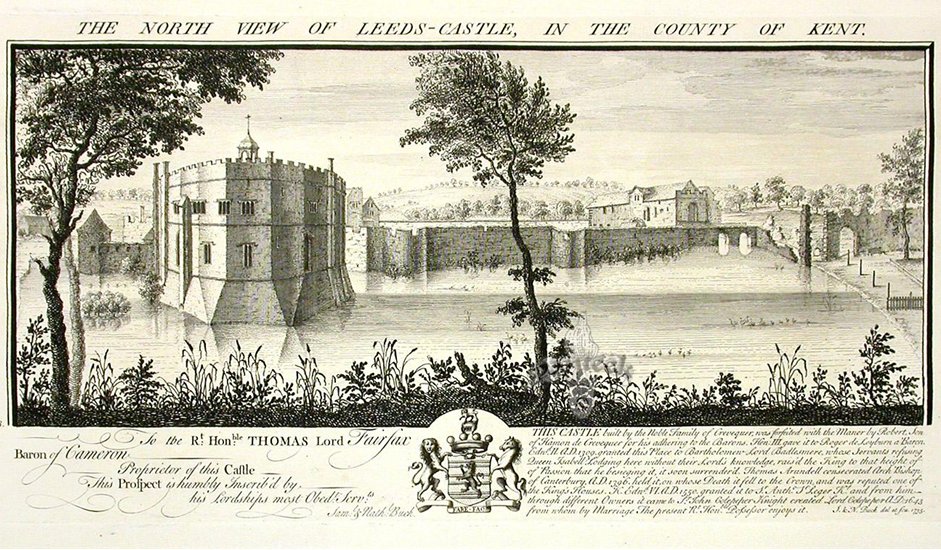

difficult to interpret. Judging from Buck's sketch, this

gatehouse backed directly onto the entrance to the inner ward.

This is an unusual design and has probably developed over the centuries

as inner and outer ward were of different builds. The rear of the

original outer ward gatetower was probably where a doorway now leads

north

into a guard's lodge. Through this to the west is what may be a

small rectangular internal turret set tight against the north wall of the

gatetower. This room is vaulted and has a crude ‘chimney'

cut through the wall. This is similar, but larger than the north

turret of the inner barbican gatehouse. The wall to the south of the

gatetower was rebuilt in the nineteenth century, so its original layout is suspect.

Within

the outer gatetower at first floor level was

a chamber from where portcullis and drawbridge were operated. Two

blocked up loops covering the approach could still be discerned in the

nineteenth century. Behind the gatetower and adjacent to it are a

series of

more modern buildings which make the original layout of this area

difficult to interpret. Judging from Buck's sketch, this

gatehouse backed directly onto the entrance to the inner ward.

This is an unusual design and has probably developed over the centuries

as inner and outer ward were of different builds. The rear of the

original outer ward gatetower was probably where a doorway now leads

north

into a guard's lodge. Through this to the west is what may be a

small rectangular internal turret set tight against the north wall of the

gatetower. This room is vaulted and has a crude ‘chimney'

cut through the wall. This is similar, but larger than the north

turret of the inner barbican gatehouse. The wall to the south of the

gatetower was rebuilt in the nineteenth century, so its original layout is suspect.

The large island, created by artificially raising

the waters by means of the barbican dams, was surrounded with a high

wall, with a strong batter to the S&W. This currently rises

some 15', directly out of the lake and still has four projecting

semi-circular towers on the north portion of the island and the remains of

a further, smaller one to the south adjoining the gatehouse block.

The best preserved tower to the NE shows that these were originally of

two storeys and the others have subsequently been lowered to battlement

level. The northtower

in the early eighteenth century had battlements, but as

these were at curtain wall height it is probable that these were post

medieval. There were also rectangular towers to the south-west,

west and south-east. The south one was of two storeys and 30' by

27'

internally,

with walls some 5' thick, but this was mostly demolished in the

nineteenth century. It appears to have held King Edward I's baths

which were built

there at a cost of some £24 towards the end of 1291. Today

only the mortar base of the 100 Reygate paving slabs remains, but the

fact that they were placed in an obviously pre-existing tower shows

that the outer ward was standing many years prior to 1291. A

sluice allowed water to flow in or out from the surrounding lake.

The upper part of the tower was removed in 1821-2, but the lower

portion was retained as a boathouse, which may have been the tower's

original purpose. Certainly there was a boat on the lake

maintained from the royal coffers in the fourteenth century.

Inner Ward

Within the outer ward was another irregular ward with a wall which was

some 8' thick and over 20' high. This enclosed the large summit

of the island. Virtually nothing of the defences of this inner

ward now remains, although a portion of its wall was still standing in

1822. This contained chimneys in the thickness of the wall and

lay under the site of the current 'new castle' or great house to

the north. The only surviving portion of the inner wall is now

thought to be the north wall of the kitchen which made up the rear wall of

the mostly destroyed rectangular NW inner ward tower.

However, underneath the ‘new castle' were some cellars which

contained two arches of ‘Caen stone'. These are thought to

be Norman.

The inner gatehouse to the south-west appears to be another

rectangular tower, similar to its now co-joined outer gatehouse.

It would appear that this originally projected inwards from the

curtain. This is adjudged as the line of the original inner

curtain wall was found to underlie the later spiral stair just over

half way along the co-joined gate passageway. The stairway now

leads up to the first floor of the rooms and over the gate passageway is

the constable's chamber. This is linked to the portcullis and

drawbridge chamber in the outer gatetower by what has been described as

a squint. This allowed the constable contact with the defenders

of that room, but not access. This room would seem to have been

in existence a long time before 1367 when a survey mentions the two

guard rooms and portcullis room, presumably of the outer gatehouse,

were covered in lead, while the constable's chamber and his stable were

tiled. This suggests that the joint inner and outer gateways were

conjoined by the mid fourteenth century at the very latest.

On the ground floor, opposite the spiral stair, is a

bench which probably dates back to the time of the construction of the

elongated gate passageway. The layout of the buildings on either

side of the gatehouse post date the destruction of this part of the

inner ward curtain. Probably they are all Tudor or later,

although the possibility remains that they are earlier. Certainly

it is evident to the rear that the entire range has been raised in

height, the original roof line being below the tops of the current

windows. It is possible that some part of this structure belonged

to the religious community that it has been suggested lived within the

castle site. If so, they would have been removed to the current

site of Leeds priory in 1119. In this case it would seem likely

that a religious community occupied this portion of the area of the

outer ward island, while the Crevecour castle was placed on the island

which is now the gloriette. Certainly the 1735 Buck's print of

the castle shows a much ruined barbican fronting the outer ward, which

looks like one long tithe barn like building with battlements only over

the N end and a gable roof running down the whole structure from there

to the S. This is only broken half way down where the internal

gatetower rises above the roof to form a dormer type roof with a window

within.

Gloriette

From the site of the gatehouse a bridge of two arches, each with a

drawbridge over them, led to the old castle or gloriette, set on a

small, artificial island. The bridge to the gloriette was

repaired in 1367 as too was the water conduit pipe that ran from the

park to the castle. As this was repaired again in 1439 the

implication is that the pipe was probably installed, or repaired,

around the end of the thirteenth century. Running water also seems to have

been installed at Goodrich castle around this time. Once over the

drawbridge the shell keep of the gloriette was entered via a

shoulder-headed doorway set in a small projecting rectangular tower,

now known as the clock tower. The tower originally had a boldly

projecting batter, like the outer gate, as well as the rest of the

gloriette. This batter was at least 17' high.

The ground floor of the gatetower could have been no

more than a gateway, just like the outer gate, but above this was a

chamber or two of which two blocked rectangular windows remain to the

west. These windows also exist to the east, with a third lower

one on

the ground floor. Both upper windows to east and west have been

curtailed by the later string course. The bulk of the masonry

above this string course is later, although the 1822 sketch of the

castle shows that the rectangular windows to east and west at the upper level

are original before the top storey of the tower was added after that

date, replacing a wooden superstructure. The upper string course

is probably later than the lower one, which probably predates the

rebuilding of the corner of the keep in 1438-41 as the course changes

height at this point. The uniform battlements from the new work

onto the bridge to the gloriette are obviously Victorian and are

lacking in the sketch of 1822. The battlements on the gloriette,

however, would appear to be medieval.

A close examination of the bridge suggests that it

originally consisted of a single, tall, central rectangular tower,

similar in dimensions to that of the clock tower. The voids

before and behind this tower were later filed in with masonry to make

the current bridge to the gloriette. The tower, now a part of the

bridge, still stands proud of the masonry that fills the gaps in over

the later arches. There also appears to be a horizontal junction

just above the level of the crown of the arches. It therefore

appears that the entrance to the gloriette began as a rectangular

gatetower with a drawbridge chamber above. These two drawbridges,

one operated from the bridge tower and the other from the clock tower,

were then fitted with stone archways. At a later date still the

gaps between the outer ward and the gatetower and the gatetower and the

clock tower were filled in with masonry which became the rooms visible

today. As the ‘footbridge' to the gloriette is mentioned in

1367 it presupposes that the two drawbridges had become a single bridge

by that date. Presumably it was later still that the bridge was

converted into the long narrow building we see today.

The walls of the gloriette, like the main medieval

castle walls, rise from the lake on a fine batter. This forms an

irregular curve to the N, although the walls rising from the batter are

straight, forming an irregular polygon. Unfortunately the

fenestration has been much altered, but several rectangular loops to

the north could well be original. To the north-west a small semi-circular

turret rises proud with the base of the batter up the wall, the only

noticeable probably medieval portion of the gloriette that projects

from the enceinte further than the gatetower. The projecting bay

windows next to this turret are much later in date and are thought to

be the work of Henry VIII. To east, west and north are corbelled out first

floor chimneys. These are unusual, but the ones at Whittington

barbican can be tentatively dated to the mid thirteenth century. Presumably

these are of a similar date.

The internal buildings of the gloriette have been

much damaged and rebuilt and little of them appears to be

medieval. To the west of the entrance was the chapel, alleged to

have been built or rebuilt by Edward I around 1280, although the castle

was then held by his queen. Such a proposition is just as likely

as not. Regardless, the chapel was heavily rebuilt and altered

into various rooms including a staircase allegedly inserted for Henry

VIII before the death of Sir Henry Guldeford in 1527. The Henry

VIII banqueting hall lay on the west side of the gloriette where the

kitchen was built after the fire caused by Dutch prisoners during the

reign of Charles II. It is possible that this chapel was also

used - or built - as the chantry founded by Edward I soon after the

death of his wife on 28 November 1290.

Central in the east wall of the gloriette is a

rectangular doorway reached from internal ground level via a spiral

stair. From here steps lead down to a vanished wooden causeway

that led to a small, now submerged, island in the lake, which roughly

marked the half way mark to the shore some 100' from the

gloriette. Presumably this was a sallyport of some description

and may date back to the earliest times of the castle. During

Charles II's reign the upper section of the gloriette between the

chimney above the sallyport and the SE corner of the keep collapsed at

first string course level. This was subsequently rebuilt soon

after

1822. The sallyport bridge was rebuilt in the 1930s for easy

access to the gloriette, but was later demolished again.

Although not a fashionable description, the gloriette has all the

attributes of a shell keep, although, like Berkely, it does not stand

on a motte.

Why not join me at Leeds and other British castles this October? Please see the information on tours at Scholarly Sojourns.

Copyright©2017

Paul Martin Remfry

Next

to the gate in the east corner of the outer

barbican was a large rectangular tower which is obviously of one build

with the rest of the barbican. This tower housed the mill and was

powered by a sluice from the lake. The mill wheel was set in a

basement chamber, while above was a rectangular room with large

embrasures and loops to the west. Above this was a further room

having much smaller embrasures of a less pointed nature holding

rectangular windows. These embrasure sizes are the reverse of

what is normally expected in towers and again emphasises how dangerous

it is to date structures upon the perceived or alleged dates of their

styles. The tower would seem to date from before

1314 when repairs to the structure and mechanism of the mill in the

castle cost 16s. Presumably the whole is twelfth century with

additions.

Next

to the gate in the east corner of the outer

barbican was a large rectangular tower which is obviously of one build

with the rest of the barbican. This tower housed the mill and was

powered by a sluice from the lake. The mill wheel was set in a

basement chamber, while above was a rectangular room with large

embrasures and loops to the west. Above this was a further room

having much smaller embrasures of a less pointed nature holding

rectangular windows. These embrasure sizes are the reverse of

what is normally expected in towers and again emphasises how dangerous

it is to date structures upon the perceived or alleged dates of their

styles. The tower would seem to date from before

1314 when repairs to the structure and mechanism of the mill in the

castle cost 16s. Presumably the whole is twelfth century with

additions. Within

the outer gatetower at first floor level was

a chamber from where portcullis and drawbridge were operated. Two

blocked up loops covering the approach could still be discerned in the

nineteenth century. Behind the gatetower and adjacent to it are a

series of

more modern buildings which make the original layout of this area

difficult to interpret. Judging from Buck's sketch, this

gatehouse backed directly onto the entrance to the inner ward.

This is an unusual design and has probably developed over the centuries

as inner and outer ward were of different builds. The rear of the

original outer ward gatetower was probably where a doorway now leads

north

into a guard's lodge. Through this to the west is what may be a

small rectangular internal turret set tight against the north wall of the

gatetower. This room is vaulted and has a crude ‘chimney'

cut through the wall. This is similar, but larger than the north

turret of the inner barbican gatehouse. The wall to the south of the

gatetower was rebuilt in the nineteenth century, so its original layout is suspect.

Within

the outer gatetower at first floor level was

a chamber from where portcullis and drawbridge were operated. Two

blocked up loops covering the approach could still be discerned in the

nineteenth century. Behind the gatetower and adjacent to it are a

series of

more modern buildings which make the original layout of this area

difficult to interpret. Judging from Buck's sketch, this

gatehouse backed directly onto the entrance to the inner ward.

This is an unusual design and has probably developed over the centuries

as inner and outer ward were of different builds. The rear of the

original outer ward gatetower was probably where a doorway now leads

north

into a guard's lodge. Through this to the west is what may be a

small rectangular internal turret set tight against the north wall of the

gatetower. This room is vaulted and has a crude ‘chimney'

cut through the wall. This is similar, but larger than the north

turret of the inner barbican gatehouse. The wall to the south of the

gatetower was rebuilt in the nineteenth century, so its original layout is suspect.