The Herefordshire Beacon and Pre-Conquest castles in England

The later days of Saxon Herefordshire, like many of the earlier ones, are shrouded in mystery. What is known is that King Edward the Confessor (1042-1066) brought many Normans over to England during his reign. One of these was Ralph Mantes (d.1057), his nephew by his sister Godgifu and Count Drogo of Vexin in the Norman March. King Edward (1042-66) made him an earl before 1050 at the latest, though whether he was earl of Hereford, a province of Earl Godwin, or not, is another matter. Ralph installed Norman favourites under his command and they immediately began constructing castles. At least 4 of these favourites seem to have settled in Herefordshire. They were Osbern Pentecost, who held Burghill and Hope of King Edward's gift and built Pentecost's Castle, Richard Fitz Scrope who held extensive lands in the north of the shire, Robert Fitz Wymarch who had Thruxton in Archenfield and a certain Hugh who left his name at Howton.

In 1052 the new customs of the Normans provoked an anti-Norman backlash from the English. This led to Earl Godwin returning from exile with an army to re-establish himself and his family against his Norman and court enemies. However, a battle was avoided and peace and concord was established between the opposing parties soon after 14 September 1052. Earl Ralph Mantes, Robert Fitz Wymarch and his son-in-law Richard Fitz Scrope and some others 'whom the king loved more than the rest', were, however, allowed to remain in England by the agreed terms. Earl Godwin may well have received Hereford back for his son, Earl Swein, but he died on 29 September 1052 and Godwin himself died on 15 April 1053. In the meantime Earl Ralph was given command of Herefordshire with Oxfordshire and possibly Gloucestershire. He seems also to have married Godwin's widow, Gytha Thorkelsdottir. This additional grant of Gloucestershire may well have had an effect on the early defensive lines established against the Welsh before the Norman Conquest. This is certainly a subject worthy of further research, especially when what occurred along the Teme valley with Richards Castle is taken into account.

Earl Ralph did not have long to consolidate his new frontier before King Gruffydd ap Llywelyn of the Welsh laid waste a great part of Herefordshire. As a consequence the men of the shire and many Normans from the castle, went against him on horseback, not as the national militia or fryd, but as mounted Norman knights. The experiment proved disastrous and the inexperienced English force was routed near Hereford on 24 October 1055 by Gruffydd who then proceeded to destroy Hereford and its castle. Ralph possibly never recovered from the disaster and died in 1057. His uninspiring attempt to convert the English to Norman knightly warfare earning him the probably unjust epitaph, Ralph the Timid. At this point Herefordshire was returned to Earl Harold, the son of Earl Godwin. He held the shire until his fall and death at Hastings as King Harold in October 1066. His Norman tenants seem to have remained in possession of their castles under him, with Robert Fitz Wymarch acting as his personal emissary to Duke William immediately before before the battle of Hastings. Perhaps then, King Harold was not so ignorant of castle-based warfare, especially when it is considered that he was recorded as building a castle at Dover.

In the 1086 Domesday book Colwall was recorded as a land claimed by the canons of Hereford. It consisted of three hides which paid tax and lay in the manor of Cradley. There were two ploughs in the lordship, eight villagers and eight smallholders with ten ploughs, six slaves, a mill, an eight acre meadow and one hay. A radman (a cavalryman) held ½ hide of the manor and had one plough. Before 1066 and in 1086 the whole was worth 60 shillings (£3). Cradley was worth £10. Earl Harold was said to have held Colwall wrongfully and one Thormod held it from him. Later King William I restored the land to Bishop Walter. In Ledbury there were five hides, ten villagers and one smallholder (buru) with eleven ploughs... Of the manor a priest held 2½ hides, two soldiers had one hide and a rider held three virgates. They had ten ploughs in lordship. There were also seven smallholders and other men with eight ploughs. The value of the land before 1066 was £10, but it had now fallen to £8. Earl Harold had wrongfully held one hide at Hazle and Godric had held this from him. Once again King William had restored it to Bishop Walter. In the lordship there were three ploughs, four villagers with three ploughs, a mill and seven acres of meadow. It was worth during the reign of Edward the Confessor, later and now 25 shillings. Nearby Coddington was also wrongfully held by Earl Harold, but again had been restored by King William. These few scarce facts tell us little of the political conditions in the manor around the conquest, but when added to the known history of Herefordshire a possible scenario does emerge.

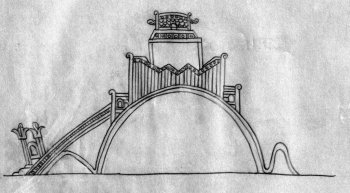

This leaves us with the interesting problem of why King Harold II was illegally holding lands from the canons of Hereford? This land seems to have lain primarily in the east of Herefordshire and have been based in the Ledbury district. Why would Earl Harold want to seize these lands? The answer is not readily apparent. However, if Harold had simply inherited these lands from his predecessor, the Norman Earl Ralph, a more logical progression can be suggested. When Ralph was given Herefordshire he was faced with several problems, not least of which was holding the Welsh at bay. It has been suggested that Richard Fitz Scrope was granted the Teme valley to stop a Welsh flanking attack with the aid of the Mercians of Shropshire as happened at least twice in the 1050s. This he succeeded in doing as late as 1067. To the west castleries existed south of the Wye at least at Ewias Harold and Clifford, though there may have been others, viz Radnor, Howton and the peculiar 'pre-Norman' phases at Monmouth. Earl Ralph certainly built a castle at Hereford and I here suggest that he also built them at Mouse castle and on the Herefordshire Beacon. The reason for suggesting this is two-fold. One is that Ralph would have wanted to protect himself from English intervention from the east as well as Welsh intervention from the west. The northern Teme line was controlled by Richard Fitz Scrope, the central Welsh frontier by his knights, one of whom was Osbern Pentecost at Ewias Harold. Howeverb it is not currently possible to speculate on what Earl Ralph’s defences were to the south in Gloucestershire. This leaves a gap to the east and I suggest that this was filled with a castle on the Herefordshire Beacon. The plan of this 'ringwork' and bailey is quite similar to that of Mouse castle and it has been suggested that Mouse is in fact a mis-translation of the Welsh word for Eye, the difference in spelling merely being the replacement of an 'a' with an 'o'. An Eye castle at this point above Hay on Wye would have had wonderful views along the Wye valley and well mirrors the position of the Herefordshire Beacon to the east.

The Herefordshire Beacon 'Citadel' was excavated in the late 1870's when the surface was much disturbed. In the 1950's the pottery evidence was re-assessed and it was concluded that it was 'twelfth century'. Consequently the old hill fort citadel was reclassified as a ringwork and bailey. This re-classification makes it worthwhile quoting verbatim Cathcart King's comment on Mouse castle at the other side of Herefordshire.

'Hummock of ground on a high foreland site occupied by what seems to be an unfinished castle of motte, bailey and counterscarp bank. The bank is strong, and the motte, in a central position, is formed by a scarped boss of rock. The defences of the bailey, however, seem generally to be lacking'.

This description is equally applicable to the Herefordshire Beacon. The question has therefore to be broached as to the age of the Herefordshire Beacon castle. Two main options seemed plausible. The first is that the castle was built during the Anarchy, when King Stephen and the Angevins were fighting in Gloucestershire, with fortified places being burnt at nearby Tewkesbury and Winchcombe. However it is considered more likely by the author that the castle should, even without conclusive evidence, be tentatively classed with other early Norman 'hill castles' like Old Sarum in Dorset or Castle Neroche in Somerset. The slight evidence accrued above may indicate that in this case the Herefordshire Beacon may actually be classified as an early pre-Norman castle! Remember that Earl Harold fortified Dover castle during the period 1053-66, according to two apparently independent sources. He also built a fortress in the Golden Valley, probably at Longtown.

Since my first book on the

Herefordshire Beacon and its castle was written in 1998 I have spent a

further ten years examining the site and its environs. The

time spent doing this has uncovered much further information about the

castle and the supposed hillfort. I advisably say supposed as

examination of the current remains show that this structure has little

similarity with the nearby Midsummer Hillfort which it is supposed to

be like in style and design. Midsummer Hillfort is a

traditional hillfort having a rampart as the main inner

defence. No such structure is to be found at the British Camp

on the Herefordshire Beacon. Instead there are a series of

earthworks belonging to at least four phases and sporting a castle on

top which itself appears to have at least two phases. In

short the British Camp is much more complex than previously envisioned.

Since my first book on the

Herefordshire Beacon and its castle was written in 1998 I have spent a

further ten years examining the site and its environs. The

time spent doing this has uncovered much further information about the

castle and the supposed hillfort. I advisably say supposed as

examination of the current remains show that this structure has little

similarity with the nearby Midsummer Hillfort which it is supposed to

be like in style and design. Midsummer Hillfort is a

traditional hillfort having a rampart as the main inner

defence. No such structure is to be found at the British Camp

on the Herefordshire Beacon. Instead there are a series of

earthworks belonging to at least four phases and sporting a castle on

top which itself appears to have at least two phases. In

short the British Camp is much more complex than previously envisioned.

The conclusion reached in this book is that the British Camp began life as a large ritual earthwork and was then expanded repeatedly. It also seems to have been used to control the salt trade to the south of Droitwich, the Saltway being diverted to pass through the site in prehistory.

The book also looks at the prehistoric landscape of the Malvern Hills in which the British Camp is set. This concludes a new origin for the so-called Red Earl's Dyke as a probably Bronze Age ritual trackway stretching some six miles. It also suggests a much more prominent role for the Malvern Hills in the life of prehistoric man. There would seem to be some evidence of the use of local hills in the vicinity with a rounded shape for religious purposes. Certainly the British Camp seems to be set within a ritual landscape.

Further documentary evidence has been uncovered concerning the castle upon the Herefordshire Beacon. This shows that a fortress was standing here in 1148 when it was under the control of the earl of Worcester. The castle had previously been held by the bishop of Hereford, which again suggests its pre-conquest foundation by one of the Saxon earls of Hereford. The castle appears to have been besieged and possibly changed hands several times in the early 1150's, before a local record states it was destroyed by King Henry II in 1155.

The new book consists of 212 A4 pages with 202 figures and photographs explaining both the prehistoric site and the castle.

New

Series!